The Administration of Indapur Pargana Under the Marathas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

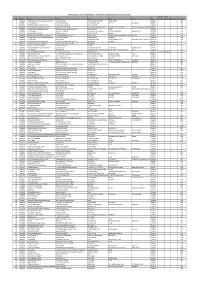

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

THE Tl1ird ENGLISH EMBASSY to POON~

THE Tl1IRD ENGLISH EMBASSY TO POON~ COMPRISING MOSTYN'S DIARY September, 1772-February, 1774 AND MOSTYN'S LETTERS February-177 4-Novembec- ~~:;, EDITED BY ]. H. GENSE, S. ]., PIL D. D. R. BANAJI, M. A., LL. B. BOMBAY: D. B. TARAPOREV ALA SONS & CO. " Treasure House of Books" HORNBY ROAD, FORT· COPYRIGHT l934'. 9 3 2 5.9 .. I I r\ l . 111 f, ,.! I ~rj . L.1, I \! ., ~ • I • ,. "' ' t.,. \' ~ • • ,_' Printed by 1L N. Kulkarni at the Katnatak Printing Pr6SS, "Karnatak House," Chira Bazar, Bombay 2, and Published by Jal H. D. Taraporevala, for D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Hornby Road, Fort, Bombay. PREFACE It is well known that for a hundred and fifty years after the foundation of the East India Company their representatives in ·India merely confined their activities to trade, and did not con· cern themselves with the game of building an empire in the East. But after the middle of the 18th century, a severe war broke out in Europe between England and France, now known as the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which soon affected all the colonies and trading centres which the two nations already possessed in various parts of the globe. In the end Britain came out victorious, having scored brilliant successes both in India and America. The British triumph in India was chiefly due to Clive's masterly strategy on the historic battlefields in the Presidencies of Madras and Bengal. It should be remembered in this connection that there was then not one common or supreme authority or control over the three British establishments or Presidencies of Bengal, Madras and Bombay. -

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Bidar District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Bidar District µ Mukhed Nandijalgaon Bawalgaon Mailur Tanda Tanda Muttakhed Chikhli Hangarga Buzurg Hokarna Tanda Tanda Aknapur Sitalcha Tanda Sawargaon Ganganbid Dapka Kherda Buzurg Ganeshpur Bonti Lingi Talab Tanda Wagangiri Doparwadi Bada Tanda Handikheda Tanda Kurburwadi Hulyal Tanda Handikheda Murki Tanda Chemmigaon Shahpurwadi Wanbharpalli Malegaon Tanda Hulyal Manur Khurd Malegaon Donegaonwadi Dongargaon Badalgaon Hakyal Dhadaknal Bhopalgad Ekamba Sangnal Nandyal Nagmarpalli Karanji Kalan Karanji Khurd Madhur Sindyal Narayanpur Dongaon Belkoni Karkyal Jaknal Ganeshpur Khelgaon Aknapur Bijalgaon Jamalpur Aurad Sundal Itgyal Mamdapur Raipalli Indiranagar Tanda Kamalanagara Tegampur Kotgial Kindekere Yengundi Lingdhalli Rampur Khasimpur Tornawadi Mudhol Tanda Murug Khurd Kamalnagar Torna Hasikera Wadi Basavanna Tanda Balur Mudhol Buzurg Naganpalli Yeklara Chintaki Digi Tuljapur Gondgaon Kollur Munganal Bardapur Munanayak Tanda Boral Beldhal Mudhol Khurd Holsamandar Lingadahalli Ashoknagar Bhimra Mansingh Tanda Aurad Chandeshwar Mahadongaon Tanda Horandi Korial Basnal Eshwarnayak Tanda Jonnikeri Tapsal Korekal Mahadongaon Lingadahalli Lingadahalli Tanda Yelamwadi Sawali Lakshminagar Kappikeri Sunknal Chandpuri Medpalli Chandanawadi Ujni Bedkonda Gudpalli Hippalgaon Maskal Hulsur Sonali Gandhinagar Khed Belkuni Jojna Alwal Sangam Santpur Mankeshwar Kalgapur Nande Nagur Horiwadi Sompur Balad Khurd Kusnur Maskal Tanda M Nagura Chikli Janwada Atnur Balad Buzurg Gangaram Tanda Jirga -

District Survey Report, Osmanabad

District Survey Report, Osmanabad (2018) Mining Section-Collectorate, Osmanabad 1 PREFACE District Survey Report has been prepared for sand mining or river bed mining as per the guidelines of the Gazette of India Notification No. S.O.141 (E) New Delhi, Dated 15th January 2016 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate mentioned in Appendix-X. District Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Assessment Committee (DEAC) have been constituted to scrutinize and sanction the environmental clearance for mining of minor minerals of lease area less than five hectares. The draft of District Survey Report, Osmanabad is being placed on the website of the NIC Osmanabad for inviting comments/suggestions from the general public, persons, firms and concerned entities. The last date for receipts of the comments/suggestion is twenty one day from the publication of the Report. Any correspondence in this regard may kindly be sent in MS- Office word file and should be emailed to [email protected] or may be sent by post to Member Secretary District level Expert Appraisal Committee Mining Section Collectorate Osmanabad 413 501 2 INDEX Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 7 3. The List of Mining Leases in the District with location, area and period of validity 9 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three years 10 5. Detail of Production of Sand or Bajari or minor mineral in last three years 10 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of the District 11 7. General Profile of the District 11 8. -

Shivaji the Founder of Maratha Swaraj

26 B. I. S. M. Puraskrita Grantha Mali, No. SHIVAJI THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ BY C. V. VAIDYA, M. A., LL. B. Fellow, University of Bombay, Vice-Ctianct-llor, Tilak University; t Bharat-Itihasa-Shamshndhak Mandal, Poona* POON)k 1931 PRICE B8. 3 : B. Printed by S. R. Sardesai, B. A. LL. f at the Navin ' * Samarth Vidyalaya's Samarth Bharat Press, Sadoshiv Peth, Poona 2. BY THE SAME AUTHOR : Price Rs* as. Mahabharat : A Criticism 2 8 Riddle of the Ramayana ( In Press ) 2 Epic India ,, 30 BOMBAY BOOK DEPOT, BOMBAY History of Mediaeval Hindu India Vol. I. Harsha and Later Kings 6 8 Vol. II. Early History of Rajputs 6 8 Vol. 111. Downfall of Hindu India 7 8 D. B. TARAPOREWALLA & SONS History of Sanskrit Literature Vedic Period ... ... 10 ARYABHUSHAN PRESS, POONA, AND BOOK-SELLERS IN BOMBAY Published by : C. V. Vaidya, at 314. Sadashiv Peth. POONA CITY. INSCRIBED WITH PERMISSION TO SHRI. BHAWANRAO SHINIVASRAO ALIAS BALASAHEB PANT PRATINIDHI,B.A., Chief of Aundh In respectful appreciation of his deep study of Maratha history and his ardent admiration of Shivaji Maharaj, THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ PREFACE The records in Maharashtra and other places bearing on Shivaji's life are still being searched out and collected in the Shiva-Charitra-Karyalaya founded by the Bharata- Itihasa-Samshodhak Mandal of Poona and important papers bearing on Shivaji's doings are being discovered from day to day. It is, therefore, not yet time, according to many, to write an authentic lifetof this great hero of Maha- rashtra and 1 hesitated for some time to undertake this work suggested to me by Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Prati- nidhi, Chief of Aundh. -

Share Liable to Be Transferres to IEPF Lying in UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT

SHARES LIABLE TO BE TRANSFERRED TO IEPF LYING IN UNCLAIMED SUSPENSE ACCOUNT Second Third S.No Folio Name Add1 Add2 Add3 Add4 PIN Holder Holder Delivery Shares 1 000010 HARENDRA KUMAR MAGANLAL MEHTA C/O SHRINAGAR 1198 CHANDNI CHOWK DELHI 110006 110006 0 480 2 000013 N S SUNDARAM 9B CLEMENS ROAD POST BOX NO 480 VEPERY CHENNAI 7 600007 0 210 3 000024 BABUBHAI RANCHHODLAL SHAH 153-D KAMLA NAGAR, DELHI-110 007. 110007 0 210 4 000036 CHANDRAKANT RAOJIBHIA AMIN M/S APAJI AMIN & CO CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS 1299/B/1 LAL DARWAJA NEAR DR K M SHAH S HOSPITAL380001 0 615 5 000042 CHAMPAKLAL ISHWARLAL SHAH 2/4456 SHIVDAS ZAVERZIS SORRI SAGRAMPARA SURAT 395002 0 7 6 000048 K V SIVANNA 181/50 4TH CROSS VYALIKAVAL EXTENSION P O MALLESWARAM BANGALORE 3 560003 0 210 7 000052 NARAYANDAS K DAGA KRISHNA MAHAL MARINE DRIVE MUMBAI 1 400001 0 210 8 000080 MANGALACHERIL SAMUEL ABRAHAM AVT RUBBER PRODUCTS LTD PLOT NO 14-C COCHIN EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE COCHIN 682030 0 502 9 000089 RAMASWAMY PILLAI RAMACHANDRAN 1 PATULLOS ROAD MOUNT ROAD CHENNAI 2 600002 0 435 10 000134 P A ANTONY JOSEALAYAM MUNDAKAPADAM P O ATHIRAMPUZHA DIST-KOTTAYAM KERALA STATE686562 0 210 11 000168 S KOTHANDA RAMAN NAYANAR 11 MADHAVA PERUMAL KOVIL ST MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600004 0 435 12 000171 JETHALAL PANJALAL PAREKH D K ARTS &SCIENCE COLLEGE JAMNAGAR 361001 0 67 13 000173 SAJINI TULSIDAS DASWANI 24 KAHUN ROAD POONA 1 411001 0 1510 14 000226 KRISHNAMOORTY VENNELAGANTI HEAD CASHIER STATE BANK OF INDIA P O GUDUR DIST NELLORE 524101 0 435 15 000227 HAR PRASAD PROPRIETOR M/S GORDHAN DASS SHEONARAINKATRA -

Chapter Three Lonavla

CHAPTER THREE LONAVLA - A REGIONAL PROFILE 3.1 Presenting Lonavla 3.2 Historical Perspective of Lonavla. 3.3 Location and Physiography of Lonavla. 3.4 Population 3.5 Climate 3.6 The Town 3.7 Occupational Structure 3.8 Land use of Lonavla 3.9 Important Tourist Destinations 55 3,1 Presenting Lonavla This chapter aims to highlight in brief the physical and demographic background of Lonavla and to show how it is a tourist place and how the local population, occupational structure and land use of Lonavla make it most important tourist destination. In short this chapter highlights the regional profile of Lonavla as a tourist centre. One of the most important hill stations in the state of Maharashtra is Lonavla. It is popularly known as the Jewel of the Sahayadri Mountains.Lonavla is set amongst the Sylvan surrounding of the w'estem ghats and is popular gateway from Mumbai and Pune. It also serves as a starting point for tourists interested in visiting the famous ancient Buddhist rock - cut caves of Bhaja and Karla, which are located near this hill station. It has some important Yoga Centres near it. There are numerous lakes around Lonavla Tungarli, Bhushi, and Walvan, Monsoon and adventure seekers can try their hand at rock climbing at the Duke’s Nose peak and other locations in the Karla hills and Forts. In order to make the travel tour to Lonavla even more joyful the right kind of accommodation is provided by the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (M.T.D.C.). The various hotels packages offer the best of facilities. -

Madhavrao Peshwe and Nizam Relationship: a New Approach

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2017; 3(12): 128-130 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal Peer Reviewed Journal Madhavrao Peshwe and Nizam Relationship: A New Refereed Journal Indexed Journal Approach UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 e-ISSN: 2454-6615 Satpute Rajendra Bhimaji Satpute Rajendra Bhimaji Abstract Head, Department of History In the history of Maratha, place of Madhavrao Peshwa has highest status. In the age of 16yrs. he got Arts and Commerce College, cloths of Peshwa, that time Maratha state had suffered from many problems. So preventing attack of Satara (Maharashtra), India Hyder Ali, Madhavrao did treaty with Nizam in 1766. In treaty with Nizam Madhavrao had many purposes behind that. Madhavrao did treaty with Nizam because of overwhelming on Janoji Bhosale, Babuji Naik and Raghobadada. In south Nizam, Maratha, Hyder Ali and British these were four main powers in 18th century, in those Maratha power was more stronger than any other. Sherjang, a sardar th of Nizam had played a vital role in occurring this treaty. In 18 century, to gain success in colonialism policy of Maratha state,it was need to prevent attack of Nizam and Hyder Ali. So firstly Peshwa did struggle with Nizam after that he made friendly relationship with him. As like Madhavrao took expeditions on Hyder Ali and did use of these expeditions, he forcedHyder Ali to become powerless in Shriranpattanam. Maratha state and Hyderabad both states got military and economic benefits by this friendly relationship. As a result, peace created in south and it was helpful to economic development of Maratha state. -

Covid 19 General Awareness List of Testing Centres & Hospitals Pan India

COVID 19 GENERAL AWARENESS LIST OF TESTING CENTRES & HOSPITALS PAN INDIA LIST OF TESTING CENTRES / LABORATORIES S. Names of Names of Government Institutes Names of Private Institutes No. States 1. Andhra 1. Sri Venkateswara Institute of Medical Pradesh (48) Sciences, Tirupati 2. Sri Venkateswara Medical College, Tirupati 3. Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada 4. Sidhartha Medical College, Vijaywada 5. Govt. Medical College, Ananthpur 6. Guntur Medical College, Guntur 7. Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Kadapa 8. Andhra Medical College, Visakhapatnam 9. Govt. Kurnool Medical College, Kurnool 10. Govt. Medical College, Srikakulam 11. Damien TB Research Centre, Nellore 12. SVRR Govt. General Hospital, Tirupati 13. Community Health Centre, Gadi Veedhi Saluru, Vizianagaram 14. Community Health Centre, Bhimavaram, West Godavari District 15. Community Health Centre, Patapatnam 16. Community Health Center, Nandyal, Banaganapalli, Kurnool 17. GSL Medical College & General Hospital, Rajahnagram, East Godavari District 18. District Hospital, Madnapalle, Chittoor District 19. District Hospital, APVVP, Pulivendula, Kadapa District 20. District Hospital, Rajahmundry, East Godavari District 21. District Hospital, Noonepalli, Nandyal, Kurnool 22. District Hospital, Anakapalli, Vishakhapatnam 23. District Hospital, Hindupur, Anantpur 24. District Hospital, Proddatur LIST OF TESTING CENTRES / LABORATORIES S. Namesof States Names of Government Institutes Names of Private Institutes No. 25. District Hospital, Machlipatnam 26. District Hospital, Atmakur 27. District Hospital, Markapur 28. District Hospital, Tekkali 29. Area Hospital, Rampachodavaram, East Godavari District 30. Area Hospital, Palamaner, Chittoor 31. Area Hospital, Amalapuram, East Godavari District 32. Area Hospital, Adoni, Kurnool 33. Area Hospital, Chirala 34. Area Hospital, Kandukuru 35. Area Hospital, Narsipatnam 36. Area Hospital, Parvathipuram 37. Area Hospital, Tadepalligudem 38. Area Hospital, Kavali 39. -

Taluka: Bhum District: Osmanabad

Patoda Bid Village Map Kaij Taluka: Bhum Lanjeshwar District: Osmanabad Nipani Malewadi Andrud Jamkhed Pakhrud Dokewadi Gikhali Ieet Giralgaon Sannewadi µ Jotibachiwadi Nali Anjan soda 3.5 1.75 0 3.5 7 10.5 km Naliwadgaon Antarwali Umachiwadi Chandwad Dudhodi Nagewadi Wadachiwadi Tintraj Ghatnandur Location Index Bagalwadi (N.V.) Jejla Irachiwadi AnandwadiNannajwadi (N.V.) Pathrud Washi District Index Nandurbar Dandegaon Dukkarwadi Bhandara Birobachiwadi Ramkund Dhule Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Jalgaon Bedarwadi Matrewadi Akola Wardha Padoli Buldana Jamb Nashik Washim Chandrapur Yavatmal Ambi Jayavantnagar Sukta Palghar Aurangabad Jalna Hingoli Gadchiroli Wakwad Burudwadi Thane Ahmednagar Parbhani Mumbai Suburban Nanded Panhalwadi Mumbai Bid Aliyabadwadi Rameshwar Songiri Ralesangvi Bavi Raigarh Pune Latur Bidar Osmanabad Warud Ulup Bhongiri Satara Solapur Bhawanwadi Krishnapur Hiwarda Ratnagiri Patsangvi Sangli Chincholi Maharashtra State Kolhapur Gormala Barhanpur Sindhudurg Dharwad Chumbli Hadongi Kasari Hiwara Warewadgaon Bhum(rural) BHUM Walwad Bhogalgaon Bhum (M C!(l) Taluka Index Walha Sadesangvi Nawalgaon Dindori Washi Bhum Kalamb Part of Bhum Taluka Chinchpur (D) Rosamba Golegaon Paranda Samangaon Wanjarwadi Ganegaon Ashtewadi Osmanabad Arsoli Belgaon Pimpalgaon Ashta Kanadi Lohara Antargaon Sawargaon Tuljapur Paranda Shekhapur Legend Umarga Pida Wangi kh. Devangra !( Taluka Head Quarter Ida Kalamb Railway Wangi Bk. District: Osmanabad Deolali National Highway State Highway Village maps from Land Record Department, GoM. Mankeshwar Data Source: Barshi Waterbody/River from Satellite Imagery. Tambewadi State Boundary District Boundary Generated By: Taluka Boundary Maharashtra Remote Sensing Applications Centre Karmala Village Boundary Autonomous Body of Planning Department, Government of Maharashtra, VNIT Campus, Waterbody/River South Am bazari Road, Nagpur 440 010. -

Unit 1 Indian Polity in the Mid-18Th Century

UNIT 1 INDIAN POLITY IN THE MID-18TH CENTURY Structure Objectives Introduction 18th Century : A Dark Age? Decline of the Mughal Empire 1.3.1 Internal Weaknesses : Struggle for Power 1.3.2 External Challenge 1.3.3 Decline : Some Interpretations 1.3.4 Continuity of Mughal Traditions The Emergence of Regional Polities 1.4.1 Successor States 1.4.2 The New Stales 1.4.3 Independent Kingdoms 1.4.4 Weakness of Regional Polities The Rise of British Power 1.5.1 From Trading Company to Political Power 1.5.2 Anglo-French Struggle in South India 1.5.3 Conquest of B~ngal: Plassey to Buxar 1.5.4 Reorganisation of the Political System Let Us Sum Up Key Words Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 1.0 OBJECTIVES The aim of this Unit is to introduce you to the main political developments in the mid- 18th century. Here we will present only an outline of the political map which the following units will fill in. After reading this Unit you will become familiar with the following themes: the declip of Mughal Empire, */the ernergma of Mughal provinces as regional power-Hyderabad. Bengal and Awadh, the rise of new staks-Marathas, Jats, Sikhs and Afghans, the history of Mysore, Rajput states and Kerala as independent principalities, and the beginnings of a colonial empire. Our study begins around 1740 and ends in 1773. The first Carnatic war and Nadir Shah's inv-n of India were the early landmarks. The last milestone was the .. reorgam#b,on. of the political system during the tenure of the Warren Hastings.