Local-Scale Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity to Climate Variability and Change: a Case Study from Northern Central Namibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W

T 0 ~ume ~-723X)Southern i\fric-a 7, Japuary-wruarv 1997 Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W. Congress Parkway, Chicago, IL 60624 phone (773) 826-4481 fax (773) 533-4728 TEARS, FEARS, AND HOPES: Healing the Memories in South Africa Pastor Philip Knutson of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, reports on a workshop he and other church leaders attended. "The farmer tied my grandfather up to a pole and told him he must get rid of all his cattle.. .! was just a boy then but I will never forget that.. .! could have been a wealthy farmer today if our fam ily had not been dispossessed in that way." The tears streamed down his face as this "coloured" pastor related his most painful experience of the past to a group at a workshop entitled "Exploring Church Unity Within the Context of Healing and Reconciliation" held in Port Elizabeth recently. A black Methodist pastor related his feelings of anger and loss at being deprived of a proper education. Once while holding a service to commemorate the young martyrs ofthe June 1976 Uprising, his con gregation was attacked and assaulted in the church. What hurt most, he said, was that the attacking security forces were black. The workshop, sponsored by the Provincial Council of Churches, was led by Fr. Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest who lost both hands and an eye in a parcel bomb attack in Harare in 1990. In his new book Partisan and Priest and in his presenta tion he said that every South African has three stories to tell. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

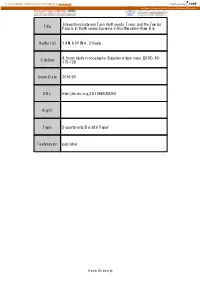

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Threatened Pastures

Himba of Namibia and Angola Threatened pastures ‘All the Himba were born here, next to the river. When the Himba culture is flourishing and distinctive. All Himba cows drink this water they become fat, much more than if are linked by a system of clans. Each person belongs to they drink any other water. The green grass will always two separate clans; the eanda, which is inherited though grow, near the river. Beside the river grow tall trees, and the mother, and the oruzo, which is inherited through the vegetables that we eat. This is how the river feeds us. father. The two serve different purposes; inheritance of This is the work of the river.’ cattle and other movable wealth goes through the Headman Hikuminue Kapika mother’s line, while dwelling place and religious authority go from father to son. The Himba believe in a A self-sufficient people creator God, and to pray to him they ask the help of their The 15,000 Himba people have their home in the ancestors’ spirits. It is the duty of the male head of the borderlands of Namibia and Angola. The country of the oruzo to pray for the welfare of his clan; he prays beside Namibian Himba is Kaoko or Kaokoland, a hot and arid the okuruwo, or sacred fire. Most important events region of 50,000 square kilometres. To the east, rugged involve the okuruwo; even the first drink of milk in the mountains fringe the interior plateau falling toward morning must be preceded by a ritual around the fire. -

Tells It All 1 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS of DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS

1989 - 2014 1989 - 2014 tells it all 1 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS Just over 25 years ago, Namibians went to the polls Elections are an essential element of democracy, but for the country’s first democratic elections which do not guarantee democracy. In this commemorative were held from 7 to 11 November 1989 in terms of publication, Celebrating 25 years of Democratic United Nations Security Council Resolution 435. Elections, the focus is not only on the elections held in The Constituent Assembly held its first session Namibia since 1989, but we also take an in-depth look a week after the United Nations Special at other democratic processes. Insightful analyses of Representative to Namibia, Martii Athisaari, essential elements of democracy are provided by analysts declared the elections free and fair. The who are regarded as experts on Namibian politics. 72-member Constituent Assembly faced a We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the FOREWORD seemingly impossible task – to draft a constitution European Union (EU), Hanns Seidel Foundation, Konrad for a young democracy within a very short time. However, Adenaur Stiftung (KAS), MTC, Pupkewitz Foundation within just 80 days the constitution was unanimously and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) adopted by the Constituent Assembly and has been for their financial support which has made this hailed internationally as a model constitution. publication possible. Independence followed on 21 March 1990 and a quarter We would also like to thank the contributing writers for of a century later, on 28 November 2014, Namibians their contributions to this publication. We appreciate the went to the polls for the 5th time since independence to time and effort they have taken! exercise their democratic right – to elect the leaders of their choice. -

Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa: the Tragedy of Endowment

alao.mech.2 5/23/07 1:42 PM Page 1 “Here is another important work from one of Africa’s finest scholars on Conflict and Security Studies. Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa is a treasure of scholarship and insight, with great depth and thoroughness, and it will put us in Abiodun Alao’s debt for quite some NATURAL RESOURCES time to come.” —Amos Sawyer, Co-director, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University AND CONFLICT “As extensive in information as it is rich in analysis, Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa IN AFRICA should help this generation of scholars appreciate the enormity and complexity of Africa’s conflicts and provide the next generation with a methodology that breaks down disciplinary boundaries.” —Akanmu G. Adebayo, Executive Director, Institute for Global Initiatives, Kennesaw State University THE TRAGEDY “Abiodun Alao has provided us with an effulgent book on a timely topic. This work transcends the perfunctory analyses that exist on natural resources and their role in African conflicts.” OF ENDOWMENT —Abdul Karim Bangura, Researcher-In-Residence at the Center for Global Peace, and professor of International Relations and Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University onflict over natural resources has made Africa the focus of international attention, particularly during the last decade. From oil in Nigeria and diamonds in the Democra- Abiodun Alao Ctic Republic of Congo, to land in Zimbabwe and water in the Horn of Africa, the poli- tics surrounding ownership, management, and control of natural resources has disrupted communities and increased external intervention in these countries. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$10.40 WINDHOEK - 9 November 2009 No. 4375 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICES No. 222 General election for the President: List of duly nominated candidates for office of President: Electoral Act, 1992 ............................................................................................................................................... 1 No. 223 General election for the President and members of the National Assembly: Notification of polling stations: Electoral Act, 1992 ................................................................................................................. 3 No. 224 General election for members of the National Assembly: Publication of party lists: Electoral Act, 1992 23 No. 225 General election for election of the President and members of the National Assembly: Notification of the final voters’ register: Electoral Act, 1992 ....................................................................................... 58 ________________ Government Notices ELECTORAL COMMISSION No. 222 2009 GENERAL ELECTION FOR THE PRESIDENT: LIST OF DULY NOMINATED CANDIDATES FOR OFFICE OF PRESIDENT: ELECTORAL ACT, 1992 In terms of section 57(3) of the Electoral Act, 1992 (Act No. 24 of 1992), and for the purpose of the general election for the office of President to be held on 27 November 2009 and 28 November 2009, notice is given that - (a) the name of each political party which has duly nominated a candidate to take part in the election for the office of President is set out in Column -

Government Gazette Republic Of

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$9.00 WINDHOEK - 14 May 2021 No. 7534 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICES No. 96 Declaration of operations at B2Gold Namibia (Pty) Ltd as continuous operations: Labour Act, 2007 2 No. 97 Notification of alteration, suspension or deletion of conditions of title of Erf 24, Karasburg: Urban and Regional Planning Act, 2018 .......................................................................................................... 2 No. 98 Amendment of Government Notice No. 60 of 31 March 2010 relating to recognition of Tsoaxudaman Customary Court as community court and appointment of assessors and justices: Community Courts Act, 2003 ................................................................................................................................................ 3 No. 99 Change of surname: Aliens Act, 1937 ................................................................................................... 4 GENERAL NOTICES No. 179 Notice of vacancy in the membership of the Village Council of Maltahöhe ......................................... 4 No. 180 Notice of vacancy in the membership of the Town Council of Karasburg ............................................ 5 No. 181 Amendment of title conditions of Erf 130, Ohangwena from “local authority” purposes to “business” purposes ................................................................................................................................................. 5 No. 182 Amendment of title conditions of Erf 167, Ohangwena from -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$45.00 WINDHOEK - 6 November 2019 No. 7041 CONTENTS Page GOVERNMENT NOTICES No. 330 Notification of polling stations: General election for the President and members of the National Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 .............................................................................................................. 1 No. 331 Notification of registered political parties and list of candidates for registered political parties: General election for election of members of national Assembly: Electoral Act, 2014 ....................................... 33 ________________ Government Notices ELECTORAL COMMISSION OF NAMIBIA No. 330 2019 NOTIFICATION OF POLLING STATIONS: GENERAL ELECTION FOR THE PRESIDENT AND MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: ELECTORAL ACT, 2014 In terms of subsection (4) of section 89 of the Electoral Act, 2014 (Act No. 5 of 2014), I make known that for the purpose of the general election of the President and members of the National Assembly - (a) polling stations have been established under subsection (1) of that section in every constituency of each region at the places mentioned in Schedule 1; (b) the number of mobile polling stations in each constituency is indicated in brackets next to the name of the constituency of a particular region and the location of such mobile polling stations will be made known by the returning officer, in terms of subsection (7) of that section, in a manner he or she thinks fit and practical; and (c) polling stations have been established under subsection (3) of that section at the Namibian diplomatic missions and at other convenient places determined by the Electoral Commission of Namibia, after consultation with the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, at the places mentioned in Schedule 2. -

The Politics of Memorialisation Reading the Independence

The Politics of Memorialisation in Namibia: Reading the Independence Memorial Museum Alexandra Stonehouse STNALE007 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Justice and Transformation Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2018 University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 18 February 2018 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract The Independence Memorial Museum is the latest addition to the post-independence memorial landscape by Namibia’s ruling party, South West African People’s Organisation (or the Swapo Party). Like many other southern African liberation movements turned ruling political parties, Swapo has looked towards history to find legitimation and support in the present. This is referred to in this research as the creation of a Swapo master narrative of liberation history. It is a selective and subjective re-telling of history which ultimately works to conflate Swapo with the Nation. -

The Indigenous Economic System in Northwest Namibia: Maintaining the Himba Tradition Through the Exchange with Others

THE INDIGENOUS ECONOMIC SYSTEM IN NORTHWEST NAMIBIA: MAINTAINING THE HIMBA TRADITION THROUGH THE EXCHANGE WITH OTHERS MIYAUCHI Yohei Department of Anthropology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] This study examines how the indigenous economy is interwoven with the modern global economy in contemporary Southern Africa by focusing on modes of exchange in Kaokoland, northwest Namibia. Himba pastoralists are the main residents of Kaokoland. Although they are recognized as the most traditional and marginalized people in Namibia, in reality, most have active relationships with neighboring peoples such as the Herero (traditionally pastoralists), the Owambo (traditionally agro-pastoralists, although many are now urban dwellers), and the Damara (agriculturalists). The Himba people keep their traditional way of life in terms of their traditional costumes and heavy dependence on livestock. At the same time, they are becoming involved in modern issues such as the development of a hydroelectric dam, the exchange of their livestock in modern livestock markets that were once forbidden, and participation in a flourishing tourism industry with many foreign tourists visiting their homesteads. A supermarket owned by white people also recently opened in Kaokoland, at which some of the Himba shop. However, most of the Himba have no source of cash income except for the occasional sales of their cattle. The area has a few informal markets or open marketplaces, where the Himba generally barter their goats for commodities and foods brought by the Owambo merchants and Damara agriculturalists. In many ways, goats serve as a sort of regional currency. In this paper, I describe some specific cases of economic exchanges in this area and propose the concept of an “indigenous economic system,” which defines how the traditional economy in remote Namibia is entangled with the modern global economy through people’s actual daily lives. -

Himba People Culture

Himba People Total population: about 50,000 Languages: OtjiHimba (Herero language dialect) Religion: Monotheistic (Mukuru and Ancestor Reverence) Related ethnic groups: Herero people, Bantu peoples Himba / OvaHimba / Himba (OmuHimba) woman The Himba (singular: OmuHimba, plural: OvaHimba) are indigenous peoples with an estimated population of about 50,000 people living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene region (formerly Kaokoland) and on the other side of the Kunene River in Angola.[1] There are also a few groups left of the Ovatwa, who are also OvaHimba, but are hunters and gatherers. The OvaHimba are a semi-nomadic, pastoral people, culturally distinguishable from the Herero people in northern Namibia and southern Angola, and speak OtjiHimba (a Herero language dialect), which belongs to the language family of the Bantu.[1] The OvaHimba are considered the last (semi-) nomadic people of Namibia. Culture Subsistence economy The OvaHimba are predominantly livestock farmers who breed fat-tailed sheep and goats, but count their wealth in the number of their cattle. They also grow and farm rain-fed-crops such as maize and millet. Livestock are the major source of milk and meat for the OvaHimba, their milk-and-meat nutrition diet is also supplemented by maize cornmeal, chicken eggs, wild herbs and honey. Only occasionally, and opportunistically, are the livestock sold for cash. Non-farming businesses, wages and salaries, pensions, and other cash remittances make up a very small portion of the OvaHimba livelihood, which is gained chiefly from