The Last Christians Last The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

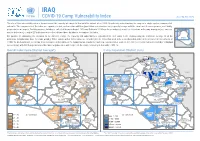

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi Idps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

COI Note on the Situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq May 20191 Contents 1) Access to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KR-I) ................................................................... 2 2) Humanitarian / Socio-Economic Situation in the KR-I ..................................................... 2 a) Shelter ........................................................................................................................................ 3 b) Employment .............................................................................................................................. 4 c) Education ................................................................................................................................... 6 d) Mental Health ............................................................................................................................ 8 e) Humanitarian Assistance ...................................................................................................... 10 3) Returns to Sinjar District........................................................................................................ 10 In August 2014, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham (ISIS) seized the districts of Sinjar, Tel Afar and the Ninewa Plains, leading to a mass exodus of Yazidis, Christians and other religious communities from these areas. Soon, reports began to surface regarding war crimes and serious human rights violations perpetrated by ISIS and associated armed groups. These included the systematic -

Doh Duhok IMC STLI Doh Ninewa Shingal Azad MSF-Swis

Minutes Meeting Health Cluster Wednesday 24 May 2017, Duhok Participants: DoH Duhok IMC STLI DoH Ninewa Shingal Azad MSF-Swiss UNHCR PUI MEDAIR WHO MdM PWJ WFP UNFPA ICRC STEP IN Capni IOM Heevie Organization Malteser International GIZ UNDP Dorcas Elise Care BRHA DoH Ninewa: Dr. Laith: The bridge in Mosul is repaired. In the old city of Mosul 200.000 are trapped. Expectation is that they will need a lot of services. TSP is needed near the bridge. There is a need to create a plan how to regulate the flow of IDPs o camps. This bridge can be used for the transferring displeased people to Duhok’s area because as he said may there will be displeased people or patients if the liberation starts from all the cities, the nearest hospital (Al- Khansaa) only have 150 beds and it’s not enough, so we have to prepare to increase the capacity of the in- patients and to establish a TSP near the bridge. The Mosul DG’s requests is that there is only 14 beds in Al- Khansaa hospital so we want to increase the capacity of ICU by the help of the partners. Regarding PHCs we need sonar and ECGs Machines, also we have a shortage of X- Ray films and syringe. Dr. Laith is explaining that the letter of the minister of Health in Bagdag regarding the recall of staff is being discussed with the deputy of MoH Bagdad. The content of the letter is not implemented at this moment by DoH Ninewa DoH Duhok: Dr. -

Poverty Rates

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mapping Poverty inIraq Mapping Poverty Where are Iraq’s Poor: Poor: Iraq’s are Where Acknowledgements This work was led by Tara Vishwanath (Lead Economist, GPVDR) with a core team comprising Dhiraj Sharma (ETC, GPVDR), Nandini Krishnan (Senior Economist, GPVDR), and Brian Blankespoor (Environment Specialist, DECCT). We are grateful to Dr. Mehdi Al-Alak (Chair of the Poverty Reduction Strategy High Committee and Deputy Minister of Planning), Ms. Najla Ali Murad (Executive General Manager of the Poverty Reduction Strategy), Mr. Serwan Mohamed (Director, KRSO), and Mr. Qusay Raoof Abdulfatah (Liv- ing Conditions Statistics Director, CSO) for their commitment and dedication to the project. We also acknowledge the contribution on the draft report of the members of Poverty Technical High Committee of the Government of Iraq, representatives from academic institutions, the Ministry of Planning, Education and Social Affairs, and colleagues from the Central Statistics Office and the Kurdistan Region Statistics during the Beirut workshop in October 2014. We are thankful to our peer reviewers - Kenneth Simler (Senior Economist, GPVDR) and Nobuo Yoshida (Senior Economist, GPVDR) – for their valuable comments. Finally, we acknowledge the support of TACBF Trust Fund for financing a significant part of the work and the support and encouragement of Ferid Belhaj (Country Director, MNC02), Robert Bou Jaoude (Country Manager, MNCIQ), and Pilar -

Iraq's Displacement Crisis

CEASEFIRE centre for civilian rights Lahib Higel Iraq’s Displacement Crisis: Security and protection © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International March 2016 Cover photo: This report has been produced as part of the Ceasefire project, a multi-year pro- gramme supported by the European Union to implement a system of civilian-led An Iraqi boy watches as internally- displaced Iraq families return to their monitoring of human rights abuses in Iraq, focusing in particular on the rights of homes in the western Melhaniyeh vulnerable civilians including vulnerable women, internally-displaced persons (IDPs), neighbourhood of Baghdad in stateless persons, and ethnic or religious minorities, and to assess the feasibility of September 2008. Some 150 Shi’a and Sunni families returned after an extending civilian-led monitoring to other country situations. earlier wave of displacement some two years before when sectarian This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union violence escalated and families fled and the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. The con- to neighbourhoods where their sect was in the majority. tents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. © Ahmad Al-Rubaye /AFP / Getty Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. -

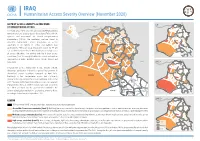

IRAQ Humanitarian Access Severity Overview (November 2020)

IRAQ Humanitarian Access Severity Overview (November 2020) DISTRICT ACCESS SEVERITY AS PERCEIVED UN BY HUMANITARIAN ACTORS TURKEY In October 2020, OCHA conducted an Access Severity monitoring Duhok exercise consisting of focus groups discussions (FGDs) with UN agencies, and international and national non-government organizations (NGOs). The monitoring exercise aimed to Erbil determine humanitarian actors’ perceptions of access constraints in all districts in central and northern Iraqi Ninewa governorates. The focus group discussions found that 47 per Al-Sulaymaniyah cent of districts covered by the HRP had moderate to high levels SYRIA Kirkuk of access difficulties. The districts with the highest access restrictions (28 of 60) mostly fall within the central and northern Salah Al-Din governorates of Anbar, Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk, Ninewa and Salah Al-Din. IRAN INGO Diyala Although the access environment in Iraq remains difficult, discussion participants indicated a general improvement in district-level access conditions compared to April 2020. Baghdad Al-Anbar Previously, in April, humanitarian access had significantly JORDAN deteriorated in Iraq compared to access conditions at the end of Wassit 2019. However, district-level humanitarian access has generally Kerbala Babil improved since then, as COVID-19 restrictions such as curfews were lifted or relaxed and the government reestablished the Maysan Al-Qadissiya Al-Najaf access authorization mechanism for granting access to NGOs Thi Qar operating in federal areas in September 2020. SAUDI ARABIA Al-Muthanna NNGO LEGEND Districts where COVID-19 related restrictions have impacted humanitarian operations Accessible / Low access constraints (Level 1): Relatively few access constraints. Armed actors, checkpoints, or other impediments such as administrative obstacles may be present and may impede humanitarian activities. -

Idpfactsheet:Duhok City

IDP FACTSHEET: DUHOK CITY DUHOK GOVERNORATE, IRAQ DISPLACEMENT CAUSES OF DISPLACEMENT DATA COLLECTED: 23 JUNE 2014 78% LEFT THEIR PLACE OF ORIGIN BECAUSE OF CONFLICT OCCURRING IN The worsening security situation in parts of northern and central Iraq has caused mass THEIR VILLAGE/NEIGHBOURHOOD OR DISTRICT internal displacement across much of the country. With the view to inform the 20% left because they anticipated conflict in their area of origin humanitarian response, the REACH Initiative is conducting rapid assessments on displacement trends and priority needs of Internally Displaced Person (IDPs). OCCURRENCES AND LENGTH OF DISPLACEMENT The city of Duhok, the largest in Duhok Governorate, 48% STOPPED FOR AT LEAST ONE NIGHT BETWEEN CROSSING THE BORDER .is roughly 470 km from Baghdad. It is a popular AND ARRIVING IN DUHOK CITY tourist destination so there is a lot of accommodation Of those who stopped prior to arriving in Duhok City (48%), 88% stopped elsewhere available which, along with the presence of family, in Duhok District greatly influences the decision of IDPs to stay there. REACH teams were rapidly deployed across the city On average, IDP families were DISPLACED FOR 2 DAYS between their and assessed 239 IDP families (1,285 individuals) place of origin and arriving in Duhok City living in rented apartments or being hosted by family. DATE OF ARRIVAL INTO DUHOK CITY 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% ENTRY POINTS USED About REACH Initiative ARRIVED THROUGH THE ADRIKA ENTRY POINT, IN TILKAIF DISTRICT REACH facilitates the development of information tools and products that enhance the capacity of 75% B aid actors to make evidence-based decisions in emergency, recovery and development contexts. -

Jivan Qasim Ahmed Flat 10, B10, Ramiland, Duhok

Jivan Qasim Ahmed Flat 10, B10, Ramiland, Duhok-Kurdistan, Iraq Mobile: 009647504907280 Email: [email protected], QUALIFICATIONS AND EDUCATION 1. Master degree in Medical virology (MSc) from The University of Manchester, 2013-2014 United Kingdom. skills learned were Cell culture, immune-assay, viral assay, molecular amplification and sequencing methods, bacterial isolation and identification, biochemical assays, as well as phylogenetic sequence analysis and Bioinformatics. Master program dissertation was entiteled Investigating the efficiency of CMV DNA detection from DBS (A dissertation submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Science in Medical virology in the Faculty of Medical & Human Sciences 2. Bachelors’ degree of veterinary medicine and surgery from University of Duhok 2010 Kurdistan region-Iraq. Learned a basic medical science in the first three years mainly physiology, Histology, anatomy, pharmacology, biochemistry, microbiology, virology, immunology, pathology etc. beside, the surgery of large and small animal, medicine, infectiouse diseases. Graduate project A review on Probiotics (A report submitted to college of Veterinary Medicine, university of Duhok in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor; graduation project). Experience and jobs: Course Rapporteur Jan/2016- present Course Rapporteur of the pathology and microbiology department at the college of veterinary medicine, university of Duhok. My resposnsibilities are forwarding the announcements of the department to the teaching staff, writing up the departments’ meeting minutes.. etc Assistant lecturer 2015- present Teaching Virology module withing the Microbiology course at the college of veterinary medicine (UoD). Teaching veterinary and zoonotic viral diseases to the the third year, in the way preparing theoretical lecture notes and practical preperations as well as responsibility of seting exams of both theorytical and practical virology module. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face. -

COI QUERY Disclaimer

COI QUERY Country of Origin/Topic Iraq Question(s) What is the security context and treatment of Christians in Iraq? 1. Background 1.1. Post-ISIL security context of Christian community - Targeted destruction of infrastructure and habitat - Targeting of Christians by armed actors 1.2. Ninewa governorate and ability to secure law and order - Governance, education and practice of Christianity in Iraq 1.3. Missing, IDPs and returnees Date of completion 22 October 2020 Query Code Q 21 Contributing EU+ COI This query response was sent to the EASO COI Specialists Network units (if applicable) on Iraq1 for contributions on the security context and treatment of Yazidis. No information was contributed by EU+ countries, but feedback was received from the Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo). Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the Common EU Guidelines for Processing COI and EASO COI Report Methodology. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever.