Investigating the Use of Wing Sweep for Pitch Control of a Small Unmanned Air Vehicle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER TWO - Static Aeroelasticity – Unswept Wing Structural Loads and Performance 21 2.1 Background

Static aeroelasticity – structural loads and performance CHAPTER TWO - Static Aeroelasticity – Unswept wing structural loads and performance 21 2.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 21 2.1.2 Scope and purpose ....................................................................................................................... 21 2.1.2 The structures enterprise and its relation to aeroelasticity ............................................................ 22 2.1.3 The evolution of aircraft wing structures-form follows function ................................................ 24 2.2 Analytical modeling............................................................................................................... 30 2.2.1 The typical section, the flying door and Rayleigh-Ritz idealizations ................................................ 31 2.2.2 – Functional diagrams and operators – modeling the aeroelastic feedback process ....................... 33 2.3 Matrix structural analysis – stiffness matrices and strain energy .......................................... 34 2.4 An example - Construction of a structural stiffness matrix – the shear center concept ........ 38 2.5 Subsonic aerodynamics - fundamentals ................................................................................ 40 2.5.1 Reference points – the center of pressure..................................................................................... 44 2.5.2 A different -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

10. Supersonic Aerodynamics

Grumman Tribody Concept featured on the 1978 company calendar. The basis for this idea will be explained below. 10. Supersonic Aerodynamics 10.1 Introduction There have actually only been a few truly supersonic airplanes. This means airplanes that can cruise supersonically. Before the F-22, classic “supersonic” fighters used brute force (afterburners) and had extremely limited duration. As an example, consider the two defined supersonic missions for the F-14A: F-14A Supersonic Missions CAP (Combat Air Patrol) • 150 miles subsonic cruise to station • Loiter • Accel, M = 0.7 to 1.35, then dash 25 nm - 4 1/2 minutes and 50 nm total • Then, must head home, or to a tanker! DLI (Deck Launch Intercept) • Energy climb to 35K ft, M = 1.5 (4 minutes) • 6 minutes at M = 1.5 (out 125-130 nm) • 2 minutes Combat (slows down fast) After 12 minutes, must head home or to a tanker. In this chapter we will explain the key supersonic aerodynamics issues facing the configuration aerodynamicist. We will start by reviewing the most significant airplanes that had substantial sustained supersonic capability. We will then examine the key physical underpinnings of supersonic gas dynamics and their implications for configuration design. Examples are presented showing applications of modern CFD and the application of MDO. We will see that developing a practical supersonic airplane is extremely demanding and requires careful integration of the various contributing technologies. Finally we discuss contemporary efforts to develop new supersonic airplanes. 10.2 Supersonic “Cruise” Airplanes The supersonic capability described above is typical of most of the so-called supersonic fighters, and obviously the supersonic performance is limited. -

The Wind Tunnel That Busemann's 1935 Supersonic Swept Wing Theory (Ref* I.) A1 So Appl Ied to Subsonic Compressi Bi1 Ity Effects (Ref

VORTEX LIFT RESEARCH: EARLY CQNTRIBUTTO~SAND SOME CURRENT CHALLENGES Edward C. Pol hamus NASA Langley Research Center Hampton, Vi i-gi nia SUMMARY This paper briefly reviews the trend towards slender-wing aircraft for supersonic cruise and the early chronology of research directed towards their vortex- 1 ift characteristics. An overview of the devel opment of vortex-1 ift theoretical methods is presented, and some current computational and experimental challenges related to the viscous flow aspects of this vortex flow are discussed. INTRODUCTION Beginning with the first successful control 1ed fl ights of powered aircraft, there has been a continuing quest for ever-increasing speed, with supersonic flight emerging as one of the early goal s. The advantage of jet propulsion was recognized early, and by the late 1930's jet engines were in operation in several countries. High-speed wing design lagged somewhat behind, but by the mid 1940's it was generally accepted that supersonic flight could best be accomplished by the now well-known highly swept wing, often referred to as a "slender" wing. It was a1 so found that these wings tended to exhibit a new type of flow in which a highly stable vortex was formed along the leading edge, producing large increases in lift referred to as vortex lift. As this vortex flow phenomenon became better understood, it was added to the designers' options and is the subject of this conference. The purpose of this overview paper is to briefly summarize the early chronology of the development of slender-wi ng aerodynamic techno1 ogy, with emphasis on vortex lift research at Langley, and to discuss some current computational and experimental challenges. -

Design of a Transonic Wing with an Adaptive Morphing Trailing Edge Via Aerostructural Optimization

Design of a Transonic Wing with an Adaptive Morphing Trailing Edge via Aerostructural Optimization David A. Burdettea, Joaquim R. R. A. Martinsa,∗ a University of Michigan, Department of Aerospace Engineering Abstract Novel aircraft configurations and technologies like adaptive morphing trailing edges offer the potential to improve the fuel efficiency of commercial transport aircraft. To accurately quantify the benefits of morphing wing technology for commercial transport aircraft, high-fidelity design optimization that considers both aerodynamic and structural design with a large number of design vari- ables is required. To address this need, we use high-fidelity aerostructural that enables the detailed optimization of wing shape and sizing using hundreds of de- sign variables. We perform a number of multipoint aerostructural optimizations to demonstrate the performance benefits offered by morphing technology and identify how those benefits are enabled. In a comparison of optimizations con- sidering seven flight conditions, the addition of a morphing trailing edge device along the aft 40% of the wing can reduce cruise fuel burn by more than 5%. A large portion of fuel burn reduction due to morphing trailing edges results from a significant reduction in structural weight, enabled by adaptive maneuver load alleviation. We also show that a smaller morphing device along the aft 30% of the wing produces nearly as much fuel burn reduction as the larger morphing device, and that morphing technology is particularly effective for high aspect ratio wings. Keywords: Morphing, Adaptive compliant trailing edge, Wing design, Aerostructural optimization, Common Research Model ∗Corresponding author Preprint submitted to Elsevier August 8, 2018 1. Introduction Increased awareness of environmental concerns and fluctuations in fuel prices in recent years have led the aircraft manufacturing industry to push for improved aircraft fuel efficiency. -

Section 7, Lecture 3: Effects of Wing Sweep

Section 7, Lecture 3: Effects of Wing Sweep • All modern high-speed aircraft have swept wings: WHY? 1 MAE 5420 - Compressible Fluid Flow • Not in Anderson Supersonic Airfoils (revisited) • Normal Shock wave formed off the front of a blunt leading g=1.1 causes significant drag Detached shock waveg=1.3 Localized normal shock wave Credit: Selkirk College Professional Aviation Program 2 MAE 5420 - Compressible Fluid Flow Supersonic Airfoils (revisited, 2) • To eliminate this leading edge drag caused by detached bow wave Supersonic wings are typically quite sharp atg=1.1 the leading edge • Design feature allows oblique wave to attachg=1.3 to the leading edge eliminating the area of high pressure ahead of the wing. • Double wedge or “diamond” Airfoil section Credit: Selkirk College Professional Aviation Program 3 MAE 5420 - Compressible Fluid Flow Wing Design 101 • Subsonic Wing in Subsonic Flow • Subsonic Wing in Supersonic Flow • Supersonic Wing in Subsonic Flow A conundrum! • Supersonic Wing in Supersonic Flow • Wings that work well sub-sonically generally don’t work well supersonically, and vice-versa à Leading edge Wing-sweep can overcome problem with poor performance of sharp leading edge wing in subsonic flight. 4 MAE 5420 - Compressible Fluid Flow Wing Design 101 (2) • Compromise High-Sweep Delta design generates lift at low speeds • Highly-Swept Delta-Wing design … by increasing the angle-of-attack, works “pretty well” in both flow regimes but also has sufficient sweepback and slenderness to perform very Supersonic Subsonic efficiently at high speeds. • On a traditional aircraft wing a trailing vortex is formed only at the wing tips. -

Fiftyyearsofthe B-52

In the skies over Afghanistan, the BUFF sees action in yet another war. Fifty Years of the B-52 By Walter J. Boyne The two B-52 prototypes—XB-52 (foreground) and YB-52—set the stage for multiple versions, one of which is still much in demand today. PRIL 15, 2002, will mark the The B-52 began projecting glob- its career is assured for at least golden anniversary of the al airpower with an epic, nonstop 20 years more. Early in its event- B-52 Stratofortress. Fifty round-the-world flight of three air- ful life, the B-52 was given the yearsA earlier, at Boeing Field, Se- craft in January 1957, and it con- affectionate nickname “BUFF,” attle, the YB-52, serial No. 49-0231, tinues to do so today. The origi- which some say stands for Big took off for the first time. No one— nal B-52 design was a triumph of Ugly Fat Fellow. not even pilots A.M. “Tex” Johnston engineering. However, its success The B-52’s stunning longevity and Guy M. Townsend—could have has depended mostly on the tal- is matched or exceeded by its imagined that the gigantic eight- ented individuals who built, flew, versatility. In the early years it engine bomber would serve so well, maintained, and modified it over functioned exclusively as a high- so long, and in so many roles. the decades. altitude strategic bomber, built to Certainly no one dreamed that Called to combat once again in overpower Soviet defenses with the B-52 would be in action over the War on Terror, the B-52 con- speed and advanced electronic Afghanistan in the fall of 2001. -

Low-Speed Aerodynamics Robert Stengel, Aircraft Flight Dynamics, MAE 331, 2018 Learning Objectives

Low-Speed Aerodynamics Robert Stengel, Aircraft Flight Dynamics, MAE 331, 2018 Learning Objectives • 2D lift and drag • Reynolds number effects • Relationships between airplane shape and aerodynamic characteristics • 2D and 3D lift and drag • Static and dynamic effects of aerodynamic control surfaces Reading: Flight Dynamics Aerodynamic Coefficients, 65-84 Copyright 2018 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE331.html http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/FlightDynamics.html 1 2-Dimensional Aerodynamic Lift and Drag 2 1 Wing Lift and Drag • Lift: Perpendicular to free-stream airflow • Drag: Parallel to the free-stream airflow 3 Longitudinal Aerodynamic Forces Non-dimensional force coefficients, CL and CD, are dimensionalized by dynamic pressure, q, N/m2 or lb/sq ft reference area, S, m2 of ft2 ⎛ 1 2 ⎞ Lift = C q S = C ρV S L L ⎝⎜ 2 ⎠⎟ ⎛ 1 2 ⎞ Drag = C q S = C ρV S D D ⎝⎜ 2 ⎠⎟ 4 2 Circulation of Incompressible Air Flow About a 2-D Airfoil Bernoullis equation (inviscid, incompressible flow) (Motivational, but not the whole story of lift) 1 p + ρV 2 = constant along streamline = p static 2 stagnation Vorticity at point x Vupper (x) = V∞ + ΔV(x) 2 ΔV(x) γ (x) = V (x) V V(x) 2 2−D lower = ∞ − Δ Δz(x) Circulation about airfoil Lower pressure on upper surface c c ΔV(x) Γ = γ (x)dx = dx 2−D ∫ 2−D ∫ 0 0 Δz(x) 5 Relationship Between Circulation and Lift Differential pressure along chord section ⎡ 1 2 ⎤ ⎡ 1 2 ⎤ Δp(x) = pstatic + ρ∞ (V∞ + ΔV (x) 2) − pstatic + ρ∞ (V∞ − ΔV (x) 2) ⎣⎢ 2 ⎦⎥ ⎣⎢ 2 ⎦⎥ 1 ⎡ 2 2 ⎤ = ρ∞ (V∞ + ΔV (x) 2) − (V∞ − ΔV (x) 2) 2 ⎣ ⎦ = ρ∞V∞ΔV (x) = ρ∞V∞Δz(x)γ 2−D (x) 2-D Lift (inviscid, incompressible flow) c c Lift = Δp x dx = ρ V γ (x)dx = ρ V Γ ( )2−D ∫ ( ) ∞ ∞ ∫ 2−D ∞ ∞ ( )2−D 0 0 1 2 ! ρ∞V∞ c(2πα ) thin, symmetric airfoil + ρ∞V∞ (Γcamber ) 2 [ ] 2−D 1 2 ! ρ V c C α + ρ V Γ 6 ∞ ∞ ( Lα ) ∞ ∞ ( camber )2−D 2 2−D 3 Lift vs. -

Boeing B-47 Stratojet™

Boeing B-47 Stratojet™ USER MANUAL Virtavia B-47E Stratojet™ – DTG Steam Edition Manual Version 2 0 Introduction The Boeing B-47™ was the first swept-wing multi-engine bomber in service with the USAF. It was truly a quantum leap in aviation history, and is the forerunner of every jet aircraft in service today. As early as 1943, Boeing™ engineers had envisaged a jet bomber, but were unable to overcome issues with the straight wings of the day. However, Boeing aero-engineer George Schairer was in Germany and came across some secret wind-tunnel data on swept-wing jet airplanes. He sent the information back to the United States, where engineers then used the Boeing High-Speed Wind Tunnel to develop the XB-47™, which featured swept-back wings. The B-47™ broke a number of records and proved to be a great strategic deterrent during the Cold War era. The B- 47E™ is an advanced version of the original XB-47, with much more powerful J-47 engines. A grand total of 2,032 of these aircraft were built, with the last one rolling out in 1956. Virtavia B-47E Stratojet™ – DTG Steam Edition Manual Version 2 1 Support Should you experience difficulties or require extra information about the Virtavia B-47E Stratojet™, please e-mail our technical support on [email protected] Copyright Information Please help us provide you with more top quality flight simulator models like this one by NOT using pirate copies. These files may not be copied (other than for backup purposes), transmitted or passed to third parties or altered in any way without the prior permission of the publisher. -

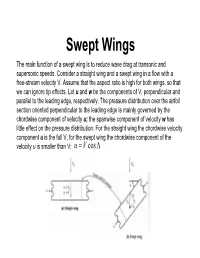

Swept Wings the Main Function of a Swept Wing Is to Reduce Wave Drag at Transonic and Supersonic Speeds

Swept Wings The main function of a swept wing is to reduce wave drag at transonic and supersonic speeds. Consider a straight wing and a swept wing in a flow with a free-stream velocity V. Assume that the aspect ratio is high for both wings, so that we can ignore tip effects. Let u and w be the components of V, perpendicular and parallel to the leading edge, respectively. The pressure distribution over the airfoil section oriented perpendicular to the leading edge is mainly governed by the chordwise component of velocity u; the spanwise component of velocity w has little effect on the pressure distribution. For the straight wing the chordwise velocity component u is the full V, for the swept wing the chordwise component of the velocity u is smaller than V: u = V cosΛ Since u for the swept wing is smaller than u for the straight wing, the difference in pressure between the top and bottom surfaces of the swept wing will be less than the difference in pressure between the top and bottom surfaces of the straight wing. Since lift is generated by these differences in pressure, the lift on the swept wing will be less than that on the straight wing. The wingspan b is the straight-line distance between the wing tips, the wing platform area is S, and the aspect ratio and the taper ratio are defined AR = b^2/S and taper ratio ct/cr. an approximate calculation of the lift slope for a swept finite wing, Kuchemann suggests the following approach. -

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Dryden Flight Research Center P.O. Box 273 Edwards, California 93523 Voice 661-276-3449 FAX 661-276-3566 [email protected] FS-2003-06-081 DFRC X-5 NASA Photo E-648. X-5 on ramp. The Bell X-5 was built to test the feasibility of changing the sweep angle of an aircraft's wings in flight. This had advantages from both an operational and research point of view. An operational aircraft could take off with its wings fully extended, reducing both its take off speed and the length of the runway needed. Once in the air, the wings could be swept back, reducing drag and increasing the aircraft's speed. For an experimental aircraft, the ability to vary the wing's sweep angle would greatly expand the research possibilities. Existing swept wing experimental aircraft, such as the D-558-II, XF-92A, X-2 and X-4, could each provide aeronautical data at only a single wing angle. A variable swept wing aircraft would be equivalent to a series of such experimental air- craft, as it could change the wing angle to the desired research objectives. Although the NACA conducted independent wind tunnel research on variable sweep wings in 1945, the X-5 originated with the Messerschmitt P.1101 experimental aircraft. This was a small jet with wings that could be adjusted on the ground to three fixed angles between 35 and 45 degrees. The P.1101 had not flown before it was captured by U.S. troops in April 1945. -

A Comparative Study of the Low Speed Performance of Two Fixed Planforms Versus a Variable Geometry Planform for a Supersonic Business Jet

Dissertations and Theses 6-2014 A Comparative Study of the Low Speed Performance of Two Fixed Planforms versus a Variable Geometry Planform for a Supersonic Business Jet Aaron C. Smelsky Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University - Daytona Beach Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/edt Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons Scholarly Commons Citation Smelsky, Aaron C., "A Comparative Study of the Low Speed Performance of Two Fixed Planforms versus a Variable Geometry Planform for a Supersonic Business Jet" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. 184. https://commons.erau.edu/edt/184 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE LOW SPEED PERFORMANCE OF TWO FIXED PLANFORMS VERSUS A VARIABLE GEOMETRY PLANFORM FOR A SUPERSONIC BUSINESS JET by Aaron C. Smelsky A Thesis Submitted to the College of Engineering, Department of Aerospace Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Aerospace Engineering at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University 2014 Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Daytona Beach, Florida June 2014 Acknowledgements Without the tremendous amount of time and effort put forth by Dr. Gonzalez with this project it would not have been possible. A great deal of gratitude is owed to him for the help editing this document. I am thankful for the quick office visits to the hours spent in his office. I not only appreciate his advice and energy during the analysis phase but also his time in the editing stage.