17 Century Quaker Roots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB. COPY# SUBJECT 1 SUBJECT 2 SUBJECT 3 NOTES NUMBER DATE Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 1 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 2 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Abbott, Margery Post Christianity and the Inner Life: PH #402 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 2009 1 Christianity - Twenty-First Century Reflections Spiritual Life on the Words of Early Friends Abbott, Margery Post To Be Broken and Tender: A 289.6 Western 2010 1 Quaker Quaker theology for today Ab2010to Friend Theology Abbott, Margery Post, Walk Worthy of Your Calling, 289.6 Friends Richmond, IN 2004 1 Pastoral Travel - Parsons, Peggy Quakers and the Traveling Ministry Ab2004wa United Press Theology - Religious Senger eds. Society of Aspects Friends Abbott, Margery Post; Historical Dictionary of Friends 289.6 Scarecrow Lanham, MD 2003 1 Society of Chijoke, Marry Ellen; (Quakers) Ab2003hi Press Friends - Dandelion, Pink; History - Oliver, John William Dictionary Abrams, Irwin To the Seeker Brochure Friends Philadelphia ND 1 Quakerism, General Introduction Conference Alexander, Horace Everyman's Struggle For Peace PH #74 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1953 2 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. Gandhi Remembered PH#165 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1969 1 Pendle Hill Gandhi, Pamphlet Mohandas - Non- violence Alexander, Horace G. Quakerism in India PH #31 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA ND 1 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. -

ABSTRACT SUFFERING and EARLY QUAKER IDENTITY: ELLIS HOOKES and the “GREAT BOOK of SUFFERINGS” by Kristel Marie Hawkins Early

ABSTRACT SUFFERING AND EARLY QUAKER IDENTITY: ELLIS HOOKES AND THE “GREAT BOOK OF SUFFERINGS” By Kristel Marie Hawkins Early Quakers formed group awareness and identification through patient suffering. The developing Quaker bureaucracy encouraged them to witness to their faith according to sanctioned practices and to have reports recorded into the “Great Book of Sufferings.” Using Lancashire as an example, this thesis examines the structure, contents, and overall purpose of the suffering accounts. The Society of Friends initially used its members’ sufferings as a public advocacy tool to end religious persecution. By the late 1680s, the focus shifted as persecution lessened. Friends subsequently sent in their reports as part of a ritual that built internal solidarity through joyful suffering and created a quasi-martyrological tradition. Beginning around 1660, Ellis Hookes, clerk to the Quakers, copied countless accounts into two volumes of the “Great Book of Sufferings.” He began a practice, which lasted over a century and filled another forty-two volumes, of linking Quakers together through their suffering accounts. SUFFERING AND EARLY QUAKER IDENTITY: ELLIS HOOKES AND THE “GREAT BOOK OF SUFFERINGS” A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Kristel Marie Hawkins Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor _______________________________ Dr. Carla Gardina Pestana Reader _______________________________ Dr. Wieste de Boer Reader _______________________________ Dr. Katharine Gillespie Table of Contents Introduction 1 Background and Centralization 6 The “Great Book of Sufferings” and Ellis Hookes 16 A Closer Examination of the “Great Book of Sufferings”: Lancashire 20 The Martyrological Context 28 Conclusion 37 Bibliography 39 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. -

16906 Dhitchcock He Is the Vagabond That Hath No Habitation in the Lord Cash 15-1-2018

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Hitchcock, D. (2018) 'He is the vagabond that hath no habitation in the Lord' the representation of Quakers as vagrants in interregnum England, 1650-1660. Cultural and Social History, 15 (1). pp. 21-37. ISSN 1478-0046. Link to official URL (if available): https://doi.org/10.1080/14780038.2018.1427340 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] 1 On 2 November 1654, in a funeral sermon on Psalm 73 (‘Thou shalt guide me with thy counsel, and afterward receive me to Glory’), the ailing Presbyterian pastor Ralph Robinson reflected on the present ‘great prosperity of the wicked’ in Protectorate England.1 As scribe to the first London Provincial assembly, and a member on its ruling council, Robinson had watched in despair as attempts to cement a Presbyterian church structure failed in the early 1650s. Also involved in a 1651 plot attempt to restore Charles II to the throne, Robinson clearly thought that England had lost its way both politically and spiritually. The metaphysical ‘wandering away from God’ he witnessed was epitomized for Robinson by the rise of radical sectarian religion. ‘We have many Spiritual Vagrants’, Robinson said, ‘but we want a Spiritual House of Correction for the punishing of these Vagrants. There are many wandring stars in the Firmament of our Church at this time… there is a generation of Ranters, Seekers, Quakers, risen up among us. -

Review of Early Quakers and Their Theological Thought

Quaker Religious Thought Volume 128 Article 3 2017 Review of Early Quakers and their Theological Thought Leah Payne George Fox Evangelical Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Payne, Leah (2017) "Review of Early Quakers and their Theological Thought," Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 128 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol128/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Religious Thought by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW OF EARLY QUAKERS AND THEIR THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT LEAH PAYNE irst-generation Quakers were a radical and persecuted sect Fof early modern British Christianity. Early Quakers and Their Theological Thought: 1647-1723 shows why the Quakers have survived when so many other 17th century radicals—including Diggers, Ranters, Levellers or Muggletonians—did not. Along the way readers also discover why the Friends, though initially derided, are so loved in the twenty-first century. Quaker theology, rejected by the powers that be in its own era, resonates with many 21st century readers. Chapters six through nine of Early Quakers include discussions of the theology of Margaret Fell, Edward Burrough, Francis Howgill, Samuel Fisher, and Dorothy White. In “Margaret Fell and the Second Coming of Christ,” Sally Bruyneel demonstrates how Fell interpreted scripture as well as how Fell’s socio-political context informed her eschatology, harmartiology, anthropology, and theology of the Trinity. -

Quakers and Conscience: Edward Burrough's

QUAKERS AND CONSCIENCE: EDWARD BURROUGH’S PROMOTION OF RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE 1653-1663 by Betty Mae Embree Veinot Submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia February 2014 © Copyright by Betty Mae Embree Veinot, 2014 DEDICATION I am dedicating this thesis in memory of my parents, Eva and Charles Embree of Springhill, Nova Scotia. They have always encouraged me in my studies and have set a glowing example of good Christian living. During the writing of this thesis, I have used the same desk my father made for me as a teenager. He resourcefully attached ¼ inch plywood over two wooden orange crates from a grocery store nearby. The plywood was varnished and covered with a blotter which has been replaced several times. This home-made desk has been functional for over sixty years. I appreciate all the sacrifices my parents have made for me and I know they have been proud of my accomplishments. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ v CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 2 THE BATTLE OF WORDS THE THEOLOGICAL DEBATE BETWEEN EDWARD BURROUGH AND JOHN BUNYAN ............................................................................................................. -

Did William Penn Diverge Significantly from George Fox in His Understanding of the Quaker Message? T

Quaker Studies Volume 11 | Issue 1 Article 4 2007 Did William Penn Diverge Significantly from George Fox in his Understanding of the Quaker Message? T. Vail Palmer Jr. Freedom Friends Church, Salem, Oregon, USA, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Palmer, T. Vail Jr. (2007) "Did William Penn Diverge Significantly from George Fox in his Understanding of the Quaker Message?," Quaker Studies: Vol. 11: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol11/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. QUAKER STUDIES QUAKER STUDIES 11 /1 (2006) [59-70) ISSN 1363-013X rks of William Penn, II, p. 873 (DQC) Jewish and more Gentile, there was a i1orning rather than Saturday evening. :! when services occurred at both times, son, C.C., 'Introduction', in his Early era] texts, including 1 Cor. 16.1-2 and 1rst-century context. l3y the beginning ence of Sunday had become assured: ~y 67 (all of which can be found in Early DID WILLIAM PENN DIVERGE SIGNIFICANTLY FROM GEORGE Fox IN HIS UNDERSTANDING 1-91 (DQC); Ingle, H.L., First Among OF THE QUAKER MESSAGE? { ork: Oxford University Press, 1994, righteousness, and peace, and joy in the T. Vail Palmer, Jr 1e holiest of all was not made manifest, a figure for the time then present, in Freedom Friends Church, Salem, Oregon, USA i1ake him that did the service pe1fect, as and drinks, and divers washings, and cmation' (Heb. -

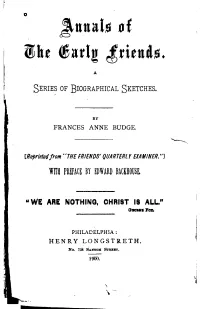

Graphical Sketches

o ~uual1J of mht ~arl! ~titu(h. A SERIES OF BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES. BY FRANCES ANNE BUDGE. [RefJrintedfrom "THE FRIENDS' QUARTERl YEXAMINER."] WITH PREFACE BY EDWARD BACKHOUSL .. WE ARE NOTHING, CHRI8T 18 ALL." CJ1Io-.w J'oz. PHILADELPHIA: HENRY LONGSTRETH. No. 738 S.A..BOX STRBBT. 1900. , I ~ CONTENTS. William Caton, I John Audland and his Friends. 28 Edward Burrough, 53 Elizabeth Stirredge, 72 William Dewsbury and his Words of Counsel and Con- solation, 92 John Crook, 104 Stephen Crisp and his Sermons, 1[9 John Banks, [36 Humphry Smith and h:s Works, [57 Mary Fisher, . [84 The Martyrs of Boston and their Friends, 207 Passagei in the Life of John Gratton, 237 James Dickenson and his Friends, 250 William Edmundson, 284 William Ellis and his Friends, 314 Richard Claridge, 345 Thomas Story, 370 Gilbert Latey and his Friends, . 399 George Whitehead, 428 PREFACE. THE Memoirs and Sketches of the lives of Friends of the Seventeenth Century, which have, from time to time, appeared in the pages of the Friends' Quarterly Examiner, are, in this volume, presented as a whole, in the hope of l:hus obtaining for them a more ex tended· circulation. They contain an account of the religious principles of the Early Friends, as well as narratives of the sufferings they underwent in main taining the testimonies committed to them by the Lord Jesus Christ; and it is hoped that their example may influence us, their successors, with boldness to maintain the Truth as it is in Jesus, and keep unfurled before the Churches the same holy banner that He has given -

John Bunyan on Justification

Midwestern Journal of Theology 10.1 (2011): 166-89 John Bunyan on Justification JOEL R. BEEKE President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Church History and Homiletics Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary Grand Rapids, MI [email protected] John Bunyan (1628–1688), author of The Pilgrim’s Progress, is one of the best-known Puritans. While much of his work is eclipsed by The Pilgrim’s Progress, the famous “tinker” from Bedford possessed remarkable theological prowess. His ability to “earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints” (Jude 1:3) is aptly demonstrated in such works as Questions about the Nature and Perpetuity of the Seventh-Day Sabbath and his Exposition of the First Ten Chapters of Genesis.1 He had no university degree, yet he clearly grasped the central tenets of the Christian faith and masterfully applied them to his readers. Bunyan was also “very distinctly and consistently a teacher,”2 whose schoolbook was the Bible. As J. H. Gosden says, “Other authority he seldom adduces...His appeal constantly is: ‘What saith the Scripture?’ ”3 Bunyan’s ability to wed orthodoxy and orthopraxy made him dangerous to his critics, beloved to his friends, and invaluable to future generations. 1 The Works of John Bunyan (ed. George Offor; 3 vols.; Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1991), 2:361–85, 413–501, henceforth cited by the title of the individual writing as well as Works, volume and page number. References to The Miscellaneous Works of John Bunyan, (ed. Roger Sharrock; 13 vols.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1976–1994) will be cited as MW, volume and page number. -

LONDON, N.W.J Quaker Books Old New

T k fc Price io/- ($2.00) THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME FORTY 1948 FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.J Quaker Books Old New We have the finest stock of Quaker books, modern and ancient A LARGE STOCK OF QUAKER PAMPHLETS FRIENDS9 BOOK CENTRE EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.I Telephone : Euston 3602 THE RELATIONS BETWEEN THE SOCIETY OF FRIENDS AND EARLY METHODISM By FRANK BAKER, B.A., B.D. (The Eayrs Prize Essay, 1948, reprinted from the London Quarterly October 1948 and April 1949) 24 pp. large 8vo. Price is. 2d. post paid, from FRIENDS BOOK CENTRE Friends House, Euston Road, London, N.W.i OR FROM The author, 40 Appleton Street, Warsop, Mansfield, Notts. Copies mil be posted immediately on publication, which will probably be in April THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XL 1948 FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE, EUSTON ROAD, LONDON, N.W.i PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY HEADLEY BROTHERS IO9 KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2 AND ASHFORD, KENT Contents PAGE Annual Meeting Norfolk Friends' Care of Their Poor, 1700-1850. Muriel F. Lloyd Prichard, M.A. (concluded) .. 3 Co-operation between English and American Friends' Libraries .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 " George Fox's Book of Miracles." Reviewed by Howard E. Collier .. .. .. .. .. 20 Quakerism in Friedrichstadt .. .. .. .. 24 Two Swarthmore Documents in America. Henry J. Cadbury, Ph.D. .. .. .. .. .. 25 William Edmundson. Isabel Grubb, M.A. .. .. 32 The First Century of Quaker Printers. Part I. Russell S. Mortimer, M.A . .. .. .. 37 John Wesley and John Bousell. Frank Baker, B.A., B.D. -

William Penn

The Journal of the r Friends 5 Historical Society VOLUME 50 NUMBER 4 1964 FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY FRIENDS HOUSE • EUSTON ROAD • LONDON N.W.i also obtainable at Friends Book Store : 302 Arch Street, Philadelphia 6, Pa., U.S.A. Yearly IDS. ______ Contents ^^M PAGE Editorial 185 Isabel Ross 186 Travel Under Concern. Elfrida Vipont Foulds 187 Early Quakerism in Newcastle upon Tyne: Thomas Ledgard's DISCOURSE CONCERNING THE QUAKERS. Roger Howell 211 Early Friends' Experience with Juries. Alfred W. Braithwaite 217 The London Six Weeks Meeting. George W. Edwards .. 228 Tangye MSS. Henry J. Cadbury 246 Seventeenth-Century Quaker Marriages in Ireland. Olive C. Goodbody 248 Reports on Archives 250 Recent Publications 252 Notes and Queries 253 •I-A A v_l.v/,^\. • • • « * * « • • • •• • • 262 Friends' Historical Society President: 1963—Russell S. Mortimer 1964—Elfrida Vipont Foulds 1965—Janet Whitney Chairman: Elfrida Vipont Foulds Secretary: Edward H. Milligan Joint Alfred W. Braithwaite and Editors: Russell S. Mortimer The Membership Subscription is los. per annum (£10 Life Membership). Subscriptions should be paid to the Secretary, c/o The Library, Friends House, Euston Road, London N.W.i. Vol. 50 No. 4 1964 THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS' HISTORICAL SOCIETY Publishing Office: Friends House, Euston Road, London, N.W. i. Communications should be addressed to the Editors at Friends House Editorial HE Presidential Address to the Friends' Historical Society for 1964 was delivered by Elfrida Vipont Foulds Ton October ist before a large and appreciative audience in the Small Meeting House at Friends House. The address, entitled: "Travel under concern—300 years of Quaker experience" forms the main item in this 1964 issue of the Journal. -

Notes and Documents

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS The Quaker Bibliographic World of Francis Daniel Past onus's Bee Hive What Quaker tracts and treatises were available in the Delaware Valley in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century? How did the published Quaker writings in early Pennsylvania compare in number and subject matter with the universe of published Quaker writings? What do their nature and content suggest about the literary, religious, political, and legal interests of early Pennsylvanians? Answers to these questions are of interest to anyone who seeks to explore the nature of print culture in colonial America.1 Francis Daniel Pastorius, who emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1683, offers assistance in developing answers to those questions. Pastorius's life touched great events in Europe and America. Born in 1651 in Sommerhausen, Germany, he was the son of a magistrate of that city. From 1668 to 1676 he was educated in law at the University of Altdorf, interspersed with time at the Universities of Jena, Regensburg, Strassburg, and perhaps Basel. Upon graduation from Altdorf in 1676, he began practicing law in Windsheim. Because of his interest in the Pietist movement centered around Frankfurt, he moved there in 1678.2 When the Frankfurt Pietists formed the Frankfurt J William Frost generously critiqued this essay and encouraged its publication I am also grateful to Bernard Bailyn, Mary Sarah Bilder, Eva Gasser, Werner Sollors, and an anonymous referee for their comments and to the Woodrow Wilson and the Robert S Kerr Foundations for financial support -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521770904 - Print Culture and the Early Quakers Kate Peters Excerpt More information Introduction The early Quaker movement is remarkable for its prolific use of the printing press. Quaker leaders began to publish their ideas in tracts and broadsides in late 1652; by the end of 1656,nearly three hundred titles had been printed, an average of more than one new Quaker book each week. Their zealous use of the press challenges established opinions about the significance of the Quakers,and about the role of print in the English revolution. Quakers in the 1650s are widely seen as a group of religious dissidents who were disillu- sioned with English political society,and who were historically significant as a thorn in the side of Commonwealth and Protectorate governments rather than for any more positive contribution. This book,based on a systematic and chronological reading of the tracts published between 1652 and 1656, and of the many letters produced by the movement’s leaders,argues on the contrary that Quakers were highly engaged with contemporary political and religious affairs,and were committed in very practical ways to the estab- lishment of Christ’s kingdom on earth. Their printed tracts were used very explicitly to involve everyone in this process,urging all people to heed the light of Christ within them,and to uphold the law of God in all aspects of religious and political life. The pamphleteering activities of the early Quaker movement demonstrate that print enabled a form of political participation in the society of the 1650s: through it,Quakers expected to achieve substantial political and religious change.