The Untouchable Classes of the Janjira State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Rajgors Auction 19

World of Coins Auction 19 Saturday, 28th June 2014 6:00 pm at Rajgor's SaleRoom 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Center, Near Church, 144 J.S.S. Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 VIEWING (all properties) Monday 23 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Category LOTS Tuesday 24 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Wednesday 25 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Ancient Coins 1-31 Thursday 26 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Hindu Coins of Medieval India 32-38 Friday 27 June 2014 11:00 am - 7:00 pm Sultanates Coins of Islamic India 39-49 Saturday 28 June 2014 11:00 am - 4:00 pm Coins of Mughal Empire 50-240 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, Coins of Independent Kingdoms 241-251 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Princely States of India 252-310 Easy to buy at Rajgor's Conditions of Sale Front cover: Lot 55 • Back cover: Lot 14 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s CONDITIONS OF SALE This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. Rajgor's Advisory Panel Corporate Office 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Center, Prof. Dr. A. P. Jamkhedkar Director (Retd.), Near Church, 144 J.S.S. -

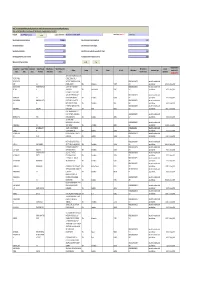

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L29120PN2009PLC133351 Prefill Company/Bank Name KIRLOSKAR OIL ENGINES LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 05-AUG-2016 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3954864.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 20TH CENTURY MUTUAL FUND SBC THCENTURYFINA CENTRE,JEHANGIR VILLA NCECORPORATI 107,WODEHOUSE ROAD COLABA, KIRL0000000000052 Amount for unclaimed and ONLT NA MUMBAI-400005 INDIA Maharashtra 400005 723 unpaid dividend 1260.00 23-Aug-2019 ABALAJICHANDR FAUMAHANESWAR 11 63 59 BRAHMIN STREET KIRL0000000000046 Amount for unclaimed and ASEKHAR A VIJAYAWADA INDIA Andhra Pradesh 520001 318 unpaid dividend 88.00 23-Aug-2019 NO 7 HARIOM COLONY WEST VANNIAR ST WEST K K NAGAR KIRL1203600000118 Amount for unclaimed and ABALARAMAN -

Surseon Generalus of United Sta Es

Treasury Department, United States Marine-Hospital Service. Published in accordance with vct of Congress approved February 15,1893. VOL. XIV. WASHINGTON, D. C., OCTOBER 27, 1899. No. 43. SURSEON GENERALUS OF UNITED STA ES. THE QUARANTINE CLOSE SEASON TO TENATE NOVEMBER 1. Amendments to quarantine regulations-Inpection of certain vesels and baggage on and after April 1 and until iNovember 1. [Department Circular No. 126.-Marine-Hospital Service.] TREASURY DEPARTMENT, OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY, Washington, D. C., October 20, 1899. To officers of the Treasury Department, State and local quarantine officers, consular officers, and others concerned: The following amendments to the quarantine regulations, to be observed at ports and on the frontiers of the United States, are hereby promulgated: Article II, paragraph 2, exception 1, is amended to read as follows: Vessels arriving during certain seasons of the year, to wit, November 1 to April 1, may be admitted to entry. Article II, paragraph 2, exception 2, is amended to read as follows: Vessels arriving during the season of close quarantine, to wit, from April 1 to November 1, shall be subject to inspection, and if necesary, to disinfection. NoTE.-The extension of inspection to November 15, under the pro- visions of Department Circular 190, of October 22, 1898, was demanded by the exigencies of war, now no longer existent. 0. L. SPAULDING, Acting Secretary. 138 127 Ootober 27, 1899 1828 [Reports to the Surgeon-General United States Marine-Hospital Service.] Yellowfever in Key West, Fla., and other pkaces. [Continued from last PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTs.] FLORIDA. Key West.-The following cases and deaths have been officially reported: October 18, 2 cases; October 19, 7 cases, no deaths; October 20, 4 cases, no deaths. -

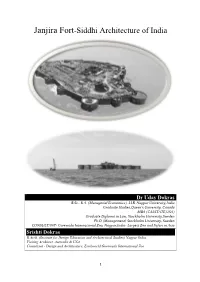

Janjira Fort-Siddhi Architecture of India

Janjira Fort-Siddhi Architecture of India Dr Uday Dokras B.Sc., B.A. (Managerial Economics), LLB. Nagpur University,India Graduate Studies,Queen’s University, Canada MBA (CALSTATE,USA) Graduate Diploma in Law, Stockholm University,Sweden Ph.D (Management) Stockholm University, Sweden CONSULTANT- Gorewada International Zoo, Nagpur,India- Largest Zoo and Safari in Asia Srishti Dokras B.Arch. (Institute for Design Education and Architectural Studies) Nagpur India Visiting Architect, Australia & USA Consultant - Design and Architecture, Esselworld Gorewada International Zoo 1 A B S T R A C T Janjira - The Undefeated Fort Janjira Fort is situated on the Murud beach in the Arabian sea along the Konkan coast line. Murud is the nearest town to the fort which is located at about 165 kms from Mumbai. You need to drive on the NH17 till Pen & then proceed towards Murud via Alibaug and Revdanda. The Rajapuri jetty is from where sail boats sail to the fort entrance. The road from murud town to janjira fort takes you a top a small hill from where you get the first glimpse of this amazing fort. Once you decent this hill, you reach Rajapuri jetty which is a small fishermen village. The sail boats take you from the jetty to the main door of the fort . One unique feature of this fort is that the entrance is not easily visible from a distance and can only be identified, once you go nearer to the walls of the fort. This was a strategy due to which Janjira was never conquered as the enemy would just keep on wondering about the entrance of the fort. -

Name Capital Salute Type Existed Location/ Successor State Ajaigarh State Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh) 11-Gun Salute State 1765–1949 In

Location/ Name Capital Salute type Existed Successor state Ajaygarh Ajaigarh State 11-gun salute state 1765–1949 India (Ajaigarh) Akkalkot State Ak(k)alkot non-salute state 1708–1948 India Alipura State non-salute state 1757–1950 India Alirajpur State (Ali)Rajpur 11-gun salute state 1437–1948 India Alwar State 15-gun salute state 1296–1949 India Darband/ Summer 18th century– Amb (Tanawal) non-salute state Pakistan capital: Shergarh 1969 Ambliara State non-salute state 1619–1943 India Athgarh non-salute state 1178–1949 India Athmallik State non-salute state 1874–1948 India Aundh (District - Aundh State non-salute state 1699–1948 India Satara) Babariawad non-salute state India Baghal State non-salute state c.1643–1948 India Baghat non-salute state c.1500–1948 India Bahawalpur_(princely_stat Bahawalpur 17-gun salute state 1802–1955 Pakistan e) Balasinor State 9-gun salute state 1758–1948 India Ballabhgarh non-salute, annexed British 1710–1867 India Bamra non-salute state 1545–1948 India Banganapalle State 9-gun salute state 1665–1948 India Bansda State 9-gun salute state 1781–1948 India Banswara State 15-gun salute state 1527–1949 India Bantva Manavadar non-salute state 1733–1947 India Baoni State 11-gun salute state 1784–1948 India Baraundha 9-gun salute state 1549–1950 India Baria State 9-gun salute state 1524–1948 India Baroda State Baroda 21-gun salute state 1721–1949 India Barwani Barwani State (Sidhanagar 11-gun salute state 836–1948 India c.1640) Bashahr non-salute state 1412–1948 India Basoda State non-salute state 1753–1947 India -

African Communities in Asia and the Mediterranean the Harriet Tubman Series on the African Diaspora

African Communities in Asia and the Mediterranean The Harriet Tubman Series on the African Diaspora Paul E. Lovejoy and Toyin Falola, eds., Pawnship, Slavery and Colonial- ism in Africa, 2003. Donald G. Simpson, Under the North Star: Black Communities in Upper Canada before Confederation (1867), 2005. Paul E. Lovejoy, Slavery, Commerce and Production in West Africa: Slave Society in the Sokoto Caliphate, 2005. José C. Curto and Renée Soulodre-La France, eds., Africa and the Americas: Interconnections during the Slave Trade, 2005. Paul E. Lovejoy, Ecology and Ethnography of Muslim Trade in West Africa, 2005. Naana Opoku-Agyemang, Paul E. Lovejoy and David Trotman, eds., Africa and Trans-Atlantic Memories: Literary and Aesthetic Mani- festations of Diaspora and History, 2008. Boubacar Barry, Livio Sansone, and Elisée Soumonni, eds., Africa, Brazil, and the Construction of Trans-Atlantic Black Identities, 2008. Behnaz Asl Mirzai, Ismael Musah Montana, and Paul E. Lovejoy, eds., Slavery, Islam and Diaspora, 2009. Carolyn Brown and Paul E. Lovejoy, eds., Repercussions of the Atlantic Slave Trade: The Interior of the Bight of Biafra and the African Diaspora, 2010. Ute Röschenthaler, Purchasing Culture in the Cross River Region of Cameroon and Nigeria, 2011. Ana Lucia Araujo, Mariana P. Candido and Paul E. Lovejoy, eds., Crossing Memories: Slavery and African Diaspora, 2011. Edmund Abaka, House of Slaves and “Door of No Return”: Gold Coast Castles and Forts of the Atlantic Slave Trade, forthcoming. AFRICAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN Identities between Integration and Conflict Edited by Ehud R. Toledano AFRICA WORLD PRESS Trenton | London | Cape Town | Nairobi | Addis Ababa | Asmara | Ibadan | New Delhi AFRICA WORLD PRESS 541 West Ingham Avenue | Suite B Trenton, New Jersey 08638 Copyright © 2011 Ehud R. -

Ti>E Ln~·OA.A. ~£J ~~Wq:!W

Ti>e ln~·OA.A. ~£J ~~wq:!w ce~nfo-eKLe _ _jf?l a(lie 13bc;- .Petnivn- / . TIIE INDIAN STATES' PEOPLE'S CONFE~ENCE. REPORT OF THE BOMBAY SESSION. 17th, 18th December 1927. PUBLISHED BY Prof, G. R. ABHYANKAR, B. A., LL.B., General Secrlta,y, MANISHANKER S. TRIVEDI, B. A., Secretary. ""he Indian States' People's Conference, V 2. - 2. p Ashoka Building, Princess Street, F7 BOMBAY. Pri.uteil by B. M. Si<lhaye, at the Bombo.y Vaibhav Press, Servants of India Society's Home, Sandhurst Road, Girgaon, Bombay. 26th SeptembP.r 1928. ~\Jo nference :JJrnbay ..~~L.., INTRODUCTORY The Problem of Indian States, always difficult, has grown tremendously so in the years after the visit of the Montague Chelmsford mission to India. The estabHshment of the Princes' Cha:nber as .a direct result of this visit, and the repercussions of the introduction of elements of Responsible Government on the states as foreshadowed by the illustrious authors of the Reforms Report are the main causes that have aroused an intelligent and keen interest in the discussion of this Problem and created a demand for constitutional rule as well as a desire for participation in all matters of common interests with the pe.:>ple of Bri:isb India on the part of the people of the Indian States. This demand has increased with years, and signs are not wanting to show us the intensity as well as the earnestness that have inspired it. The People of the States have begun organising themselves by various rueanR. The establishment of the Deccan States Conference, the Kathiawar States Political Conference, the Rajputena Seva Sangha, and such other activities v:orking for the Political rights of the people of groups of Indian ~:tates, as well as Conferences of the people of individual States such as the Sangli State's People's C~nference, the Bhor Political Conference, the Bhavnagar Praja Parishad, the Cutchi Praja Parishad and tile Hyderabad State People's Conference, Janjira State Subjects Cou1erence, Miraj State People's Conference and the !dar Praja Parishad are the clear manifestations of the New Spirit that is abroad. -

Lighthouses in India During the 19Th & 20Th Centuries- Above All to Mr John Oswald and Mr S.K

INDIAN LIGHTHOUSES – AN OVERVIEW CONTENTS Foreword Preface Indian Lighthouse Service – An introduction Lighthouses and Radar Beacons [Racons] The story of Radio Beacons Decca Chain & Loran -C Chain References Abbreviations Drawings Lighthouses through Ages Light sources Reflectors and Refractors Photographs Write up notes Index Lighthouses on West Coast Kachchh & Saurashtra Gulf of Khambhat & Maharashtra Goa, Kanataka & Kerala Lakshadweep & Cape Lighthouses on East Coast Tamilnadu & Andhra Orissa & West Bengal Lighthouses in Andaman & Nicobar Islands Bay Islands Andaman & Nicobar FOREWORD The contribution saga of Indian Lighthouses in enriching the Indian Maritime Tradition is long and cherished one. A need was felt for quite some time to compile data on Indian Lighthouses which got shape during the eighth Senior Officers meeting where it was decided to bring out a compilation of Indian Lighthouses. The book is an outcome of two years rigorous efforts put in by Shri R.K. Bhanti, Director (Civil) who visited all the lighthouses in pursuit of collecting data on Lighthouses. The Lighthouse-generations to come will fondly remember his contribution. “Indian Lighthouses- an Overview” is a first ever book on Indian Lighthouses which gives implicit details of Lighthouses with a brief historical background. I am hopeful this book will be useful to all concerned. 21st July, 2000 J. RAMAKRISHNA Director General PREFACE The Director General Mr. J. Ramakrishna, when in December, 1997, asked me to document certain aspects of changes which took place at each Lighthouse during different periods of time, and compile them into a book, little did I realise at that time that the job was going to be quite tough and a time consuming project. -

Public Health Reports

PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS. UNITED STATES. Agreement for cooperative work between Treasury Department and State and muniipal reresentatives of alifornia and San Francisco. In accordance with the agreement entered into between the State and local authorities of the State of California and city of San Francisco and the Treasury Department, the work of inspection, isolation, and disin- fection in Chinatown, San Francisco, is progressing under the advice and direction of Surg. J. H. White, U. S. Marine-Hospital Service, assisted by the following commissioned officers of the U. S. Marine- Hospital Service and acting asistant surgeons, namely: P. A. Surg. Rupert Blue,- Assistant Surgeons H. B. Parker, M. J. White, W. C. Billings, G. M. Corput, and D. H. Currie, and Acting Asistant Surgeons J. M. Flint and H. A. L. Ryfkogel, bacteriologists. A corps of interpreters, disinfectors, etc., have also been engaged. A corps of physicians, appointed by the city authorities of San Fran- cisco, and State representatives are also at work under the same arrangement. Referring to the findings and full report of the special commission, as published in PUBLIC HEALTH REPORTS of March 22, March 29, and April 19, 1901, and to the misstatements in certain daily and medical publications regarding an agreement made between officials of the Treasury Department and representatives of California and San Fran- cisco, the only agreement entered into is herewith published. TREASURY DEPARTMENT, OFFICE SUPERVISING SURGEON-GENERAL, U. S. M. H. S., Washington, D. a., March 9, 1901. SIR: Referring to the conference, held in accordance with your instructions after the meeting in your office this forenoon, with the representatives of the governor of California, the mayor of San Fian- cisco, the press, the railroads, and the business interests of San Fran- cisco, I have to inform you that an. -

Map Thawing the Regioncu Baehgroand of Kathiawar KATHIAWAR ECONOMICS

Map thawing the RegioncU Baehgroand of Kathiawar KATHIAWAR ECONOMICS BY A. B. TRIVEDI, M.A.,B.Com., (Banking* Accounting); Preject, University Hostel; Research Scholar, University School of Economics and Sociology; Member Professor C. N. Vakil's Economic Seminar; Investigator, N, D.: Bombay Economic and Industrial Survey Committee; and Lecturer in Economics and Geography) Khalsa College, Bombay. AUTHOR OF STUDIES IN GUJARAT ECONOMICS SERIES: (1) The Gold Thread Industry of Surat, (2) Wood Work and Metal Work of Gujarat (Radio Talk), (3) Fire Works of Gujarat (Radio Talk). (4) Plight of Handloom Industry in Gujarat (Memo• randum submitted to the Handloom Fact Finding Committee), (5) The Washers Manufacturing Industry of Gujarat, etc., etc. 1943. First Published: January 1943 Printed by Mr. R. R. BAKHALE, at the Bombay Vaibhav Press, Sandhurst Road, Bombay 4. and Published by Prof. A. B. TRIVEDI, M.A., B.com., Khalsa College, Bombay 19. To LATE SHETH HARGOVANDAS JIVANDAS, J. P. Late Sheth Hargovandas Jivandas, J.P. who rose to high eminence by sheer hard work and abilities. Born of poor parents and though deprived of the chances of taking University Education, this great industrialist of Kathiawar, showed remarkable business acumen from his early life. He rose with occasions and opportunities and led a very successful life. His life will be a fountain of knowledge, revealing the fruits of patience, perseverance and for• bearance, to the future generations. Born in 7874, he died at the age of 68 in 1942. A short sketch of his career appears in the following pages. SHORT SCETCH OF THE CAREER OF LATE SHETH HARGOVANDAS Sheth Hargovandas Jivandas, J. -

Rajgor Auction 51 Final DR

Internet Auction Auction 51 World of Coins Saturday, 25th June 2016 Closing from 3:00 pm onwards VIEWING For Closing Schedule Monday 20 June 2016 11:00 am - 6:00 pm refer page 3 Tuesday 21 June 2016 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 22 June 2016 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Thursday 23 June 2016 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Friday 24 June 2016 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Saturday 25 June 2016 11:00 am - 1:00 pm At Rajgor’s SaleRoom 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Category LOTS Ancient Coins 1-4 Hindu Coins of Medieval India 5-7 Sultanate Coins of Islamic India 8-9 Coins of Mughal Empire 10-20 Coins of Independent Kingdoms 21-38 DELIVERY OF LOTS Princely States of India 39-159 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Mumbai Office of European Powers in India 160-171 the Rajgor’s. British India 172-186 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 187-206 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 207-227 CONDITIONS OF SALE Tokens 228-236 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale Medals 237-243 and to Reserves Seals, Badges& Collectibles 244-256 ONLINE CATALOGUE Paper Money 257-266 View catalogue and leave your bids online at www.Rajgors.com Front cover: Lot 228 • Back cover: Lot 262 Corporate Office 6th Floor, Majestic Shopping Center, Near Church, 144 J.S.S. Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 T: +91-22-23820 647 M: +91-9594 647 647 • F: +91-22-23870 647 E: [email protected] • W: www.Rajgors.com W: www.MyHobbyy.com : @rajgorsauctoins : /rajgorsauctoins Catalogue by Dr.