Language and National Identity in Theodor Adorno and WG Sebald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definingromanticnationalism-Libre(1)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Notes towards a definition of Romantic Nationalism Leerssen, J. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Published in Romantik Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Leerssen, J. (2013). Notes towards a definition of Romantic Nationalism. Romantik, 2(1), 9- 35. http://ojs.statsbiblioteket.dk/index.php/rom/article/view/20191/17807 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 NOTES TOWARDS A DEFINITION Romantic OF ROMANTIC Nationalism NATIONALISM [ JOEP LEERSSEN ABSTR While the concept ‘Romantic nationalism’ is becoming widespread, its current usage tends to compound the vagueness inherent in its two constituent terms, Romanticism and na- tionalism. In order to come to a more focused understanding of the concept, this article A surveys a wide sample of Romantically inflected nationalist activities and practices, and CT nationalistically inflected cultural productions and reflections of Romantic vintage, drawn ] from various media (literature, music, the arts, critical and historical writing) and from dif- ferent countries. -

(De)Constructing Boundaries

21st Harvard East Asia Society Graduate Conference (DE)CONSTRUCTING BOUNDARIES 9-10 February, 2018 21st Annual Harvard East Asia Society Graduate Conference (DE)CONSTRUCTING BOUNDARIES CGIS South, Harvard University 9-10 February, 2018 Abstract Booklet 1 Table of Contents Welcome Note 3 Sponsors 4 Keynote Speakers 5 Campus Map 6 Harvard Guest Wi-fi access 6 Panel Information 7 Panel A: (De)constructing Nation: Gendered Bodies in the Making of Modern Korea 7 Panel B: Urban Fabrics Unraveled 9 Panel C: Reimagining the boundary of novelistic styles in Pre-modern East Asia 10 Panel D: Transmission and Displacement in Literature 12 Panel E: Reframing Regionalism in East Asia 14 Panel F: Art and Visual Culture in Context 16 Panel G: Traversing Boundaries in Education 18 Panel H: Transnationalism in the Age of Empire 20 Panel I: Re-examining Boundaries in Chinese Politics in Xi Jinping's "New Era" 23 Panel K: Media Across Boundaries 28 Panel L: De(constructing) Myths of Migration 29 2 Welcome Note Welcome to the 21st annual Harvard East Asia Society Conference! It is our privilege to host graduate students working across all disciplines to exchange ideas and discuss their research related to Asia. In addition to receiving feedback from their peers and leading academics, participants have the opportunity to meet others doing similar research and forge new professional relationships. This year’s theme, “(De)constructing Boundaries”, critically assesses boundaries - physical, national, cultural, spatial, temporal, and disciplinary - between different spatial- temporal areas of study. As the concept of “Asia” continues to evolve, the construction and deconstruction of boundaries will enable redefinitions of collective knowledge, culture, and identity. -

Qualitative Freedom

Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Translated by Richard Fincham Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Qualitative Freedom - Autonomy in Cosmopolitan Responsibility Claus Dierksmeier Institute of Political Science University of Tübingen Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany Translated by Richard Fincham American University in Cairo New Cairo, Egypt Published in German by Published by Transcript Qualitative Freiheit – Selbstbestimmung in weltbürgerlicher Verantwortung, 2016. ISBN 978-3-030-04722-1 ISBN 978-3-030-04723-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04723-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018964905 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Helmut Walser Smith, "Nation and Nationalism"

Smith, H. Nation and Nationalism pp. 230-255 Jonathan Sperber., (2004) Germany, 1800-1870, Oxford: Oxford University Press Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2012 Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich Max Schiller Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Schiller, Max, "Jürgen Habermas and the Third Reich" (2012). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 358. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/358 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction The formation and subsequent actions of the Nazi government left a devastating and indelible impact on Europe and the world. In the midst of general technological and social progress that has occurred in Europe since the Enlightenment, the Nazis represent one of the greatest social regressions that has occurred in the modern world. Despite the development of a generally more humanitarian and socially progressive conditions in the western world over the past several hundred years, the Nazis instigated one of the most diabolic and genocidal programs known to man. And they did so using modern technologies in an expression of what historian Jeffrey Herf calls “reactionary modernism.” The idea, according to Herf is that, “Before and after the Nazi seizure of power, an important current within conservative and subsequently Nazi ideology was a reconciliation between the antimodernist, romantic, and irrantionalist ideas present in German nationalism and the most obvious manifestation of means ...modern technology.” 1 Nazi crimes were so extreme and barbaric precisely because they incorporated modern technologies into a process that violated modern ethical standards. Nazi crimes in the context of contemporary notions of ethics are almost inconceivable. -

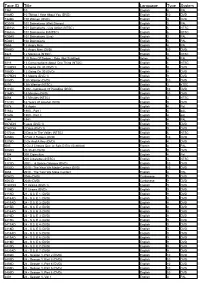

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Definition of Pantomime: A Theatrical Entertainment, Mainly for Children

Definition of Pantomime: A theatrical entertainment, mainly for children, which involves music, topical jokes, and slapstick comedy and is based on a fairy tale or nursery story, usually produced around Christmas. A typical Pantomime storyline: Normally, a pantomime is an adapted fairytale so it is usually a magical love story which involves something going wrong (usually the fault of an evil baddy) but the ending (often after a fight between good and evil) is always happy and results in true love. Key characters in Pantomime: The female love interest, e.g Snow White, Cinderella etc The Handsome Prince e.g Prince Charming The evil character e.g the evil Queen in Snow White The faithful sidekick - e.g Buttons in Cinderella The Pantomime Dame - provides most of the comedy - an exaggerated female, always played by a man for laughs How to act in a pantomime style: 1. Your character is an over-the-top type’, not a real person, so exaggerate as much as you can, in gesture, voice and movement 2. Speak to the audience - if you are a ‘Goody’, your character must be likeable or funny. If you are a ‘Baddy’, insult your audience, make them dislike you from the start. 3. There is always a narrator - make sure she knows speaks confidently and knows the story well. 4. Encourage the audience to be involved by asking for the audience’s help, e.g “If you see that naughty boy will you tell me?” 5. If you are playing that ‘naughty boy’, make eye contact with the audience and creep on stage. -

A Church Undone

1 The Original Guidelines of the German Christian Faith Movement Joachim Hossenfelder Introduction These ten guidelines were written by Pastor Joachim Hossenfelder and published in June 1932. Key words and phrases point to some of the movement’s preoccupations. “Positive Christianity” refers directly to the same phrase in Point 24 of the 1920 platform of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party.1 The German Christians favor a “heroic piety,” reject both the “weak” leadership and the 1. A “positive Christianity” was understood to be beyond denominations and emphasized an “active,” heroic Christ. That Hitler included this in the platform signaled his sense that he would need the support of the churches as he embarked on his National Socialist project. 45 A CHURCH UNDONE “parliamentarianism” of the church as it is presently configured, and dedicate themselves to the battle against Marxism. The guidelines spell out the movement’s conviction that “race, ethnicity [ ] Volkstum , and nation” are “orders of life given and entrusted to us by God.” The movement opposes “race-mixing,” the “mission to the Jews,” and both pacifism and “internationalism.” In every important respect this self-identified Christian movement resonates with and reflects all the important commitments favored by the National Socialists. The following year the movement’s guidelines were revised; a slightly muted text left out all references to Jews and Judaism.2 2. Find the revised guidelines translated as part of Arnold Dannenmann’s The History of the , pp. 121ff in this volume. German Christian Faith Movement 46 THE ORIGINAL GUIDELINES Figure 1. German text of “Guidelines of the German Christian Faith Movement” 47 A CHURCH UNDONE The Original Guidelines of the German Christian Faith Movement 3 (1932) Joachim Hossenfelder 1. -

Dr. Eric Kurlander Professor of Modern European History Stetson University

Dr. Eric Kurlander Professor of Modern European History Stetson University Department of History Office: (386) 822-7578 Elizabeth Hall, Unit 8344 (386) 822-7535 421 N. Woodland Blvd. Fax: (386) 822-7544 Stetson University Email: [email protected] Deland, FL 32724 EDUCATION HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, MA PhD, Modern European History. 2001 MA, Modern European History. 1997 BOWDOIN COLLEGE Brunswick, ME BA, summa cum laude. History and English (minor). 1994 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Professor, History Department, Stetson University Spring 2015 - present Professor and Chair, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2013 – Fall 2014 Associate Professor and Chair, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2010 – Spring 2013 Visiting Professor and Fulbright Fellow, History Department, Freiburg Pädagogische Hochschule January 2012 – July 2012 Associate Professor, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2007 – Spring 2010 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow, History Department, University of Bonn/Berlin December 2007 – June 2008 Thyssen-Heideking Fellow, Anglo-American Institute, University of Cologne June 2007 – February 2008 Assistant Professor, History Department, Stetson University Fall 2001 – Spring 2007 Assistant Senior Tutor, Currier House, Harvard University Fall 2000 – Spring 2001 Teaching Fellow, History Department, Harvard University Fall 1999 – Spring 2001 SELECTED PUBLICATIONS (2001 – present) Books Hitler’s Monsters: A Supernatural History of the Third Reich. New Haven and London: Yale University Press (under contract). The West in Question: Continuity and Change. v. II. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press (under contract) Monica Black and Eric Kurlander, eds., Revisiting the Nazi Occult: Histories, Realities, Legacies. Rochester: Camden House, 2015. Joanne Miyang Cho, Eric Kurlander, and Douglas McGetchin, eds., Transcultural Encounters between Germany and India: Kindred Spirits in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, New York and London: Routledge, 2014. -

The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations

Colby Quarterly Volume 28 Issue 3 September Article 7 September 1992 Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations Collin Meissner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 28, no.3, September 1992, p.164-174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Meissner: Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and t Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations 1 by COLLIN MEISSNER Ifpoetry were to be extinguished, my people, Ifwe were without history and ancient lays Forever. Everyone will pass unheralded. Giolla Brighde Mac Con Mighde2 Sirrah, your Tongue betrays your Guilt. You are an Irishman, and that is always sufficient Evidence with me. Justice Jonathan Thrasher, Fielding's Amelia3 etus begin by acknowledging that language is often employed as a political, L military, and economic resource in cultural, particularly colonial, encoun ters. Call it a weapon. Henry VIII's 1536 Act of Union decree is as good an example as any: "Be it enacted by auctoritie aforesaid that all Justices Commis sioners Shireves Coroners Eschetours Stewardes and their Lieuten'ntes, and all other Officers and Ministers ofthe Lawe, shall pclayme and kepe the Sessions Courtes ... and all other Courtes, in the Englisshe Tongue and all others of Officers Juries and Enquetes and all other affidavithes v~rdictes and wagers of 1. -

A Study of Alterity and Influence in the Literary and Philosophical Neighbourhood of Jean Genet and Emmanuel Levinas

A study of alterity and influence in the literary and philosophical neighbourhood of Jean Genet and Emmanuel Levinas Thomas F. Newman University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2008 UMI Number: U593B63 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U593363 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this PhD is my own. This thesis is the one on which I wish to be examined. Thomas F. Newman 29 January 2008 2 Thesis Abstract The dissertation is a chiasmic reading of the works of Jean Genet and Emmanuel Levinas, examining the way they each address the relation to the Other in terms of ethics and subjectivity. Whereas a straightforward association between the two writers might seem paradoxical because of the differences in their approaches and rhetoric, a chiasmic reading allows intricate approaches, moments of proximity and departures to be read both conceptually and aesthetically. We show that these two writers share a tightly-woven discursive neighbourhood, and examine that neighbourhood through detailed analysis of various textual encounters. -

After Babel Revisited: on Language and Translation. in Memoriam George Steiner (1929–2020)

Athens Journal of Philology 2020, 7: 1-22 https://doi.org/10.30958/ajp.X-Y-Z After Babel Revisited: On language and Translation. In Memoriam George Steiner (1929–2020) By Hans-Harry Drößiger On February 3, 2020, one of the most interesting scholars in humanities, especially in literary research and translation studies, died: George Steiner. Sometimes labelled as a genius, sometimes as someone who was always outside the mainstream and acting as an inconvenient thinker, he did his part in the humanities in a fresh and in a provocative way. The following article wants to shed some light on his basic writing entitled After Babel, originally published in 1975 and reviewed by himself in 1992. In doing so, this article is about to honour him for his challenging statements, insights and discussion on language and translation to be not forgotten by recent and future generations of researchers. Keywords: George Steiner, language, translation, theory of translation, contiguity. We are able to say so fantastically much more than we would need to for purposes of physical survival. We mean endlessly more than we say (Steiner 1998: 296). Introduction First published in 1975, this volume by George Steiner gained appreciation and interest amongst scholars in the world because of its fresh, lively and competent description of translation problems and issues, not only for his time. Thus, this book requires our full attention because of its fascinating range of thoughts on language, translation and translation theory. Excerpts from the contemporary press in the scholarly world from the back cover of that edition I own, may highlight the value the book deserves even today.