Bruckner ~ Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

Two Letters by Anton Bruckner

Two Letters by Anton Bruckner Jürgen Thym Bruckner ALS, 13.XI.1883 Lieber Freund! Auf Gerathewohl schreibe ich; denn Ihr Brief ist versteckt. Weiß weder Ihre Adresse noch sonstigen Charakter von Ihnen. Danke sehr für Ihr liebes Schreiben. Omnes amici mei dereliquerunt me! In diesen Worten haben Sie die ganze Situation. Hans Richter nennt mich jetzt musik [alischen] Narren weil ich zu wenig kürzen wollte; (wie er sagt;) führt natürlich gar nichts auf; ich stehe gegenwärtig ganz allein da. Wünsche, daß es Ihnen besser ergehen möge, und Sie bald oben hinauf kommen mögen! Dann werden Sie gewiß meiner nicht vergessen. Glück auf! Ihr A. Bruckner Wien, 13. Nov. 1883 Dear Friend: I take the risk or writing to you, even though I cannot find your letter and know neither your address nor title. Thank you very much for your nice letter. All my friends have abandoned me! These words tell you the whole situation. Hans Richter calls me now a musical fool, because I did not want to make enough cuts (as he puts it). And, of course, he does not perform anything at all; I stand alone at the moment. I hope that things will be better for you and that you will soon succeed then you will surely not forget me. Good luck! Your A. Bruckner Vienna, November 13, 1883 Bruckner, ALS, 27.II.1885 Hochgeborener Herr Baron! Schon wieder muß ich zur Last fallen. Da die Sinfonie am 10. März aufgeführt wird, so komme ich schon Sonntag den 8. März früh nach München und werde wieder bei den vier Jahreszeiten Quartier nehmen. -

Das Brucknerhaus in Linz (Oberösterreich)

Das Brucknerhaus in Linz (Oberösterreich) ©Kutzler+Wimmer+Stöllinger Lange schon, bevor das Konzerthaus tatsächlich gebaut wurde, stand bereits fest, wie es genannt wird: nach Anton Bruckner, dem bedeutendsten Komponisten Oberösterreichs. Das Brucknerhaus ist ein Konzert- und Veranstaltungshaus. Es wurde 1974 nach Plänen der finnischen Architekten Kaija und Heikki Sirén in Linz an der Donau gebaut und mit besonderem Bedacht auf hervorragende akustische Eigenschaften geplant. Das Brucknerhaus trug für den Komponisten viel zu seiner weltweiten Bekanntheit bei. Kurz nach der Eröffnung durch Herbert von Karajan und den Wiener Philharmonikern wurde das Musikfestival des Brucknerhauses, das Brucknerfest ins Leben gerufen, bei dem jedes Jahr hochkarätige internationale Künstler und Ensembles auftreten. Einige Daten zum Haus: Veranstaltungen pro Jahr: ca. 200 Eigenveranstaltungen: ca. 120 Gastveranstaltungen: ca. 80 Besucher: 180.000 Niveau: A1 Lernziel: über Musikvorlieben sprechen Fertigkeit: Sprechen Sozialform: Gruppenarbeit Welche Arten von Musik kennst du? Ergänze die Liste: Klassik, Schlager, Rock, … Welche Arten von Musik magst du, welche mögen deine Freunde? Welche Bands gefallen euch? Frag in deiner Gruppe und erzähle, welche Musik deine Freunde gerne hören. Verwende dabei folgende Wörter: mögen, gerne haben, lieben, gerne hören. Beispiel: Ich mag Jazz, Klara mag lieber Popmusik. Niveau: A2 Lernziel: Vergangenheitsformen ergänzen Fertigkeit: Lesen Sozialform: Gruppenarbeit Warum heißt das Brucknerhaus Brucknerhaus? Im folgenden Text fehlen einige Wörter. Du findest sie im Kasten. Setze die fehlenden Wörter in der richtigen Form ein und beachte die Zeitform. sterben werden gehören werden haben werden sein haben sein Joseph Anton Bruckner _wurde_ am 4. September 1824 in Ansfelden, Oberösterreich, geboren und ___________ am 11. Oktober 1896 in Wien. Er __________ ein österreichischer Komponist der Romantik sowie Orgelspieler und Musikpädagoge. -

Vespers 2020 Music Guide

MILLIKIN UNIVERSITY® 2 0 2 0 ALL IS BRIGHT MUSIC GUIDE VESPERS MEANS ‘EVENING’ AND IS ONE OF THE SEVEN CANONICAL HOURS OF PRAYER. MILLIKIN UNIVERSITY | SCHOOL OF MUSIC BELL CAROL (2017 All Choirs) William Mathias “AlltheBellsonEarthShallRing”wastheVespersthemeinMathias’compositionwastheperfect openingTheprocessionendeavorstorevealtoaudiencemembersthatbellsaregiftssounds(musicifyou will)oeredtothemangerIndeedtheremainderoftheprogramdisplayedbellsinbothcelebratoryand reflectivemomentsThepiecewascomposedforSirDavidWillcocksthechoirmasterwhobroughtsomuch attentiontotheLessonsandCarolsofKing’sCollegeCambridge ALLELUIA(2018 University Choir) Fredrik Sixten “SingAlleluia”wasthethemeofVespersinandSixten’sreflectivesettingcameearlyintheprogram givingthiswordusuallyconsideredfestiveinmoodasenseofadventhope LAUDATE DOMINUM (2015 Millikin Women) Gyöngyösi Levente LaudateDominumhasservedmanycomposersinincludingMozartwhouseditinhiswellknownSolemn VespersContemporaryHungariancomposerGyöngyösicombinesanincessantmantraonasinglenotewith complexrhythmsforthissettingofPs(“OPraisetheLordallyenations”)Harmonicdensityincreasesand joinstherhythmicdrivetothefinalAlleluiawheretheadditionofatambourineaddsafinalcelebratorynote MAGNIFICAT(2017 Collegiate Chorale) Bryan Kelly EvensongtheAnglicanversionofVespersalwaysincludesasettingoftheMagnificatEventhough thisiscomposedforEnglishearsBryanKelly’senthusiasmforLatinAmericanmusicisclearlyevident inthissettingfromthes GLORIA PATRIMAGNIFICAT (2019 All Choirs) John Rutter ThefinalmovementofRutter’sMagnificatgathersmanyofthework’sthemesintoatriumphantfinale -

Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg

BLÄSERPHILHARMONIE MOZARTEUM SALZBURG DANY BONVIN GALACTIC BRASS GIOVANNI GABRIELI ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER RICHARD STRAUSS ANTON BRUCKNER WERNER PIRCHNER CD 1 WILLIAM BYRD (1543–1623) (17) Station XIII: Jesus wird vom Kreuz GALAKTISCHE MUSIK gewesen ist. In demselben ausgehenden (1) The Earl of Oxford`s March (3'35) genommen (2‘02) 16. Jahrhundert lebte und wirkte im Italien (18) Station XIV: Jesus wird ins „Galactic Brass“ – der Titel dieses Pro der Renaissance Maestro Giovanni Gabrieli GIOVANNI GABRIELI (1557–1612) Grab gelegt (1‘16) gramms könnte dazu verleiten, an „Star im Markusdom zu Venedig. Auf den einander (2) Canzon Septimi Toni a 8 (3‘19) Orgel: Bettina Leitner Wars“, „The Planets“ und ähnliche Musik gegenüber liegenden Emporen des Doms (3) Sonata Nr. XIII aus der Sterne zu denken. Er meint jedoch experimentierte Gabrieli mit Ensembles, „Canzone e Sonate” (2‘58) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACh (1685–1750) Kom ponisten und Musik, die gleichsam ins die abwechselnd mit und gegeneinander (19) Passacaglia für Orgel cMoll, BWV 582 ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER (*1943) Universum der Zeitlosigkeit aufgestiegen musizierten. Damit war die Mehrchörigkeit in der Fassung für acht Posaunen sind, Stücke, die zum kulturellen Erbe des gefunden, die Orchestermusik des Barock Via Crucis – Übermalungen nach den XIV von Donald Hunsberger (6‘15) Stationen des Kreuzweges von Franz Liszt Planeten Erde gehören. eingeleitet und ganz nebenbei so etwas für Orgel, Pauken und zwölf Blechbläser, RICHARD STRAUSS (1864–1949) wie natürliches Stereo. Die Besetzung mit Uraufführung (20) Feierlicher Einzug der Ritter des William Byrd, der berühmteste Komponist verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten war flexibel JohanniterOrdens, AV 103 (6‘40) Englands in der Zeit William Shakespeares, und wurde den jeweiligen Räumen ange (4) Hymnus „Vexilla regis“ (1‘12) hat einen Marsch für jenen Earl of Oxford passt. -

Bruckner Und Seine Schüler*Innen

MUTIGE IMPULSE BRUCKNER UND SEINE SCHÜLER*INNEN Bürgermeister Klaus Luger Aufsichtsratsvorsitzender Mag. Dietmar Kerschbaum Künstlerischer Vorstandsdirektor LIVA Intendant Brucknerhaus Linz Dr. Rainer Stadler Kaufmännischer Vorstandsdirektor LIVA VORWORT Anton Bruckners Die Neupositionierung des Inter- ein roter Faden durch das Pro- musikalisches Wissen nationalen Brucknerfestes Linz gramm, das ferner der Linzerin liegt mir sehr am Herzen. Ich Mathilde Kralik von Meyrswal- Der Weitergabe seines Wissens förderprogramm mit dem Titel wollte es wieder stärker auf An- den einen Schwerpunkt widmet, im musikalischen Bereich wid- an_TON_Linz ins Leben gerufen ton Bruckner fokussieren, ohne die ebenfalls bei Bruckner stu- mete Anton Bruckner ein beson- hat. Es zielt darauf ab, künstleri- bei der Vielfalt der Programme diert hat. Ich freue mich, dass deres Augenmerk. Den Schü- sche Auseinandersetzungen mit Abstriche machen zu müssen. In- viele renommierte Künstler*in- ler*innen, denen er seine Fähig- Anton Bruckner zu motivieren dem wir jede Ausgabe unter ein nen und Ensembles unserer keiten als Komponist vermittelt und seine Bedeutung in eine Motto stellen, von dem aus sich Einladung gefolgt sind. Neben hat, ist das heurige Internationa- Begeisterung umzuwandeln. bestimmte Aspekte in Bruckners Francesca Dego, Paul Lewis, le Brucknerfest Linz gewidmet. Vor allem gefördert werden Pro- Werk und Wirkung beleuchten Sir Antonio Pappano und den Brucknerfans werden von den jekte mit interdisziplinärem und lassen, ist uns dies – wie ich Bamberger Symphonikern unter Darbietungen der sinfonischen digitalem Schwerpunkt. glaube – eindrucksvoll gelungen. Jakub Hrůša sind etwa Gesangs- ebenso wie der kammermusika- Als Linzer*innen können wir zu Dadurch konnten wir auch die stars wie Waltraud Meier, Gün- lischen Kompositionen von Gus- Recht stolz auf Anton Bruckner Auslastung markant steigern, ther Groissböck und Thomas tav Mahler und Hans Rott sowie sein. -

25232 Cmp.Pdf

El Concurs Internacional de Cant "Francisco Viñas" és membre de la Federació de Concursos Inter nacionals de Música. EL DR. JACINT VILARDELL I PERMANYER, FUNDADOR DEL CONCURS INTERNACIONAL DE CANT "FRANCISCO VIÑAS" S. M. LA REINA D'ESPANYA, PRESIDENTA D'HONOR DEL CONCURS INTERNACIONAL DE CANT "FRANCISCO VIÑAS" MOLT HONORABLE SR. JORDI PUJOL, PRESIDENT DE LA GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA, VICE-PRESIDENT D'HONOR DEL CONCURS INTERNACIONAL DE CANT "FRANCISCO VIÑAS" PÒRTIC Per a tots el molt barcelonins, però especialment per a aquells que vivim immersos en la febre musical, i especialment en la lírlca, arriba a la fi del mes de puntualment, novembre, i així des de fa 22 anys, el Concurs Internacional de Cant Francesc Viñas que, a la memòria del nostre fundà gloriós tenor, el doctor Jacint Vilardell, gran senyor de la ciència i de la cultura Ifrica. Patrocinat per: Jo no tenir la sort de vaig coneixer-Io, però sf, en canvi, he estat a graciat per la de conèixer la seva filla Maria, ànima i vida del certamen en Generalitat de Catalunya, aquests moments; aixf com al seu nét Miquel Lerin, que ha recollit també la invalidant en de Barcelona, torxa, aquesta ocasió aquella teoria tant catalana Ajuntament que les terceres són les '" generacions encarregades de destruir les Provincial de 1 Diputació Barcelona, grans obres de llurs progenitors i avantpassats. Ministeri d'Afers Exteriors, Els conec Patronat "Francisco Viñas", des de fa molts anys, tants com els transcorreguts entre aquell primer Concurs, que es va celebrar en el Fundació Francisca de que ja comença a "Maria Roviralta", i la ésser llunya any 1962, present edició, i aixó m'ha estat útil per Accademia de admirar-los Chigiana Siena, per molts motius, però, bàsicament, per llur claretat i cons tància en Amics de l'Òpera de Sabadell. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 97, 1977-1978

97th SEASON BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Miistc Director mm . TRUST BANKING. A symphony in financial planning. Conducted by Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company Decisions which affect personal financial goals are often best made in concert with a professional advisor. However, some situations require consultation with a number of professionals skilled in different areas of financial management. Real estate advisors. Tax consultants. Estate planners . Investment managers To assist people with these needs, our venerable Boston banking institution has developed a new banking concept which integrates all of these professional services into a single program. The program is called trust banking. Orchestrated by Roger Dane, Vice President, 722-7022, for a modest fee. DIRECTORS HansH. Estin George W. Phillips C. Vincent Vappi Vernon R. Alden Vice Chairman, North Executive Vice President, Vappi & Chairman, Executive American Management President Company, Inc. Committee Corporation George Putnam JepthaH. Wade Nathan H. Garrick, Jr. Partner, Choate, Hall DwightL. Allison, Jr. Chairman, Putnam of the Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman Management & Stewart Board David C. Crockett Company, Inc. William W.Wolbach Donald Hurley Deputy to the Chairman J. John E. Rogerson Vice Chairman Partner, Goodwin, of tne Board of Trustees Partner, Hutchins & of the Board Proctor Hoar and to the General & Wheeler Honorary Director Director, Massachusetts Robert Mainer Henry E. Russell Sidney R. Rabb General Hospital Senior Vice President, President Chairman, The Stop & The Boston Company, Companies, Inc. F. Stanton Deland, Jr. Mrs. George L. Sargent Shop Partner, Sherburne, Inc. Director of Various Powers & Needham William F. Morton Corporations Director of Various Charles W. Schmidt Corporations President, S.D. -

Contents Price Code an Introduction to Chandos

CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION TO CHANDOS RECORDS An Introduction to Chandos Records ... ...2 Harpsichord ... ......................................................... .269 A-Z CD listing by composer ... .5 Guitar ... ..........................................................................271 Chandos Records was founded in 1979 and quickly established itself as one of the world’s leading independent classical labels. The company records all over Collections: Woodwind ... ............................................................ .273 the world and markets its recordings from offices and studios in Colchester, Military ... ...208 Violin ... ...........................................................................277 England. It is distributed worldwide to over forty countries as well as online from Brass ... ..212 Christmas... ........................................................ ..279 its own website and other online suppliers. Concert Band... ..229 Light Music... ..................................................... ...281 Opera in English ... ...231 Various Popular Light... ......................................... ..283 The company has championed rare and neglected repertoire, filling in many Orchestral ... .239 Compilations ... ...................................................... ...287 gaps in the record catalogues. Initially focussing on British composers (Alwyn, Bax, Bliss, Dyson, Moeran, Rubbra et al.), it subsequently embraced a much Chamber ... ...245 Conductor Index ... ............................................... .296 -

Selected Male Part-Songs of Anton Bruckner by Justin Ryan Nelson

Songs in the Night: Selected Male Part-songs of Anton Bruckner by Justin Ryan Nelson, B.M., M.M. A Dissertation In Choral Conducting Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved John S. Hollins Chair of Committee Alan Zabriskie Angela Mariani Smith Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May 2019 Copyright 2019, Justin Ryan Nelson Texas Tech University, Justin R. Nelson, May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To begin, I would like to thank my doctoral dissertation committee: Dr. John Hollins, Dr. Alan Zabriskie, and Dr. Angela Mariani Smith, for their guidance and support in this project. Each has had a valuable impact upon my life, and for that, I am most grateful. I would also like to thank Professor Richard Bjella for his mentorship and for his uncanny ability to see potential in students who cannot often see it in themselves. In addition, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Alec Cattell, Assistant Professor of Practice, Humanities and Applied Linguistics at Texas Tech University, for his word-for-word translations of the German texts. I also wish to acknowledge the following instructors who have inspired me along my academic journey: Dr. Korre Foster, Dr. Carolyn Cruse, Dr. Eric Thorson, Mr. Harry Fritts, Ms. Jean Moore, Dr. Sue Swilley, Dr. Thomas Milligan, Dr. Sharon Mabry, Dr. Thomas Teague, Dr. Jeffrey Wood, and Dr. Ann Silverberg. Each instructor made an investment of time, energy, and expertise in my life and musical growth. Finally, I wish to acknowledge and thank my family and friends, especially my father and step-mother, George and Brenda Nelson, for their constant support during my graduate studies. -

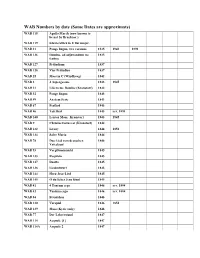

WAB Numbers by Date (Some Dates Are Approximate) WAB 115 Apollo March (Now Known to Be Not by Bruckner.) WAB 119 Klavierstück in E Flat Major

WAB Numbers by date (Some Dates are approximate) WAB 115 Apollo March (now known to be not by Bruckner.) WAB 119 Klavierstück in E flat major. WAB 31 Pange lingua, two versions 1835 1843 1891 WAB 136 Domine, ad adjuvandum me 1835 festina WAB 127 Präludium 1837 WAB 128 Vier Präludien 1837 WAB 25 Mass in C (Windhaag) 1842 WAB 3 2 Asperges me 1843 1845 WAB 21 Libera me Domine (Kronstorf) 1843 WAB 32 Pange lingua 1843 WAB 59 An dem Feste 1843 WAB 67 Festlied 1843 WAB 86 Tafellied 1843 rev. 1893 WAB 140 Lenten Mass, Kronstorf 1843 1845 WAB 9 Christus factus est (Kronstorf) 1844 WAB 132 Litany 1844 1858 WAB 134 Salve Maria 1844 WAB 78 Das Lied vom deutschen 1845 Vaterland WAB 93 Vergißmeinnicht 1845 WAB 133 Requiem 1845 WAB 137 Duetto 1845 WAB 138 Liedentwurf 1845 WAB 144 Herz-Jesu-Lied 1845 WAB 145 O du liebes Jesu Kind 1845 WAB 41 4 Tantum ergo 1846 rev. 1888 WAB 42 Tantum ergo 1846 rev. 1888 WAB 84 Ständchen 1846 WAB 130 Vorspiel 1846 1852 WAB 139 Mass (Kyrie only) 1846 WAB 77 Der Lehrerstand 1847 WAB 114 Aequale {1} 1847 WAB 114A Aequale 2 1847 WAB 131 Vorspiel und Fuge 1847 WAB 17 In jener letzten der Nächte 1848 WAB 43 Tantum ergo 1848 1849 WAB 85 Sternschnuppen 1848 WAB 39 Requiem 1849 rev. 1892 WAB 120 Lancier-Quadrille (after 1850 Lortzing and Donizetti) WAB 122 Steiermärker 1850 WAB 14 Entsagen 1851 WAB 65 Das edle Herz, 1st setting 1851 WAB 68 Frühlingslied 1851 WAB 69 Die Geburt 1851 WAB 83 2 Motti 1851 WAB 24 Magnificat 1852 WAB 34 Psalm 22 (23) 1852 WAB 36 Psalm 114 (116a) 1852 WAB 47 Totenlied 1 1852 WAB 48 Totenlied 2 1852 WAB 61 Auf, Brüder, auf zur 1852 Rev. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files.