Feature: Local Currency: a Legal and Policy Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall of the Global Gold Exchange Standard and the Formation of The

European Research Studies Journal Volume XXIV, Special Issue 1, 2021 pp. 341-347 Fall of the Global Gold Exchange Standard and the Formation of the Contemporary Free Gold Market Submitted 20/01/21, 1st revision 15/02/21, 2nd revision 03/03/21, accepted 20/03/21 Dariusz Eligiusz Staszczak1 Abstract: Purpose: The purpose of this paper is an explanation of the fall of the global gold exchange standard in the beginning of XXth century. Moreover, reasons of the cancelations of the U.S. dollar convertibility into gold according to the fixed parity in 1933 and 1971 are purposes of this paper. The final cancellation of the U.S. dollar gold convertibility was related to the establishment of the free gold market in 1968-1974. A lack of the gold standard and the free gold market are characteristic features of the contemporary world market system. Design / Methodology / Approach: The design is finding the historical reasons of the fall of the global gold exchange standard and of the establishment of the free gold market in 1968- 1974. The research method is a describing political-economic analysis based on statistical data. The approach covers the most important historical time periods connected with the transformation of the global market system including the changing role of the gold. Findings: This paper analyses reasons of the fall of the gold exchange standard from the beginning of the XXth century to the establishment of the free gold market in 1968-1974. Author considers this problem including changes of the global political-economic situation in the analyzed period. -

SAGA COMMUNICATIONS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Letter To our fellow shareholders: Every now and then I am introduced to someone who knows, kind of, who I am and what I do and they instinctively ask, ‘‘How are things at Saga?’’ (they pronounce it ‘‘say-gah’’). I am polite and correct their pronunciation (‘‘sah-gah’’) as I am proud of the word and its history. This is usually followed by, ‘‘What is a ‘‘sah-gah?’’ My response is that there are several definitions — a common one from 1857 deems a ‘‘Saga’’ as ‘‘a long, convoluted story.’’ The second one that we prefer is ‘‘an ongoing adventure.’’ That’s what we are. Next they ask, ‘‘What do you do there?’’ (pause, pause). I, too, pause, as by saying my title doesn’t really tell what I do or what Saga does. In essence, I tell them that I am in charge of the wellness of the Company and overseer and polisher of the multiple brands of radio stations that we have. Then comes the question, ‘‘Radio stations are brands?’’ ‘‘Yes,’’ I respond. ‘‘A consistent allusion can become a brand. Each and every one of our radio stations has a created personality that requires ongoing care. That is one of the things that differentiates us from other radio companies.’’ We really care about the identity, ambiance, and mission of each and every station that belongs to Saga. We have radio stations that have been on the air for close to 100 years and we have radio stations that have been created just months ago. -

The Pre-History of Self-Determination: Union and Disunion of States in Early Modern International Law

THE PRE-HISTORY OF SELF-DETERMINATION: UNION AND DISUNION OF STATES IN EARLY MODERN INTERNATIONAL LAW Han Liu* TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ 2 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 2 II. THE STATE AND THE NATION STATE ................................................................... 7 III. TERRITORIAL ACCESSION IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE ...................................... 9 A. The King and the Sovereign .......................................................................... 9 B. Land and Territory ....................................................................................... 15 1. Division of Realms ................................................................................... 17 2. Land and Sovereignty............................................................................... 18 3. Dynastic-Patrimonial Territoriality .......................................................... 20 4. Shape of Early Modern Territory ............................................................. 22 C. Aggregating Land: Conquest and Inheritance.............................................. 24 IV. OUTSIDE EUROPE: LAND APPROPRIATION AND COLONIAL EXPANSION........... 27 A. Just War as Civilizing Process: Vitoria’s Catholic Argument ..................... 29 B. Conquest or Settlement: Locke, Vattel, and the Protestant Argument ........ 31 V. THE JURIDICIAL -

Monetary Policy in a World of Cryptocurrencies∗

Monetary Policy in a World of Cryptocurrencies Pierpaolo Benigno University of Bern March 17, 2021 Abstract Can currency competition affect central banks’control of interest rates and prices? Yes, it can. In a two-currency world with competing cash (material or digital), the growth rate of the cryptocurrency sets an upper bound on the nominal interest rate and the attainable inflation rate, if the government cur- rency is to retain its role as medium of exchange. In any case, the government has full control of the inflation rate. With an interest-bearing digital currency, equilibria in which government currency loses medium-of-exchange property are ruled out. This benefit comes at the cost of relinquishing control over the inflation rate. I am grateful to Giorgio Primiceri for useful comments, Marco Bassetto for insightful discussion at the NBER Monetary Economics Meeting and Roger Meservey for professional editing. In recent years cryptocurrencies have attracted the attention of consumers, media and policymakers.1 Cryptocurrencies are digital currencies, not physically minted. Monetary history offers other examples of uncoined money. For centuries, since Charlemagne, an “imaginary” money existed but served only as unit of account and never as, unlike today’s cryptocurrencies, medium of exchange.2 Nor is the coexistence of multiple currencies within the borders of the same nation a recent phe- nomenon. Medieval Europe was characterized by the presence of multiple media of exchange of different metallic content.3 More recently, some nations contended with dollarization or eurization.4 However, the landscape in which digital currencies are now emerging is quite peculiar: they have appeared within nations dominated by a single fiat currency just as central banks have succeeded in controlling the value of their currencies and taming inflation. -

A Model of Bimetallism

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department A Model of Bimetallism François R. Velde and Warren E. Weber Working Paper 588 August 1998 ABSTRACT Bimetallism has been the subject of considerable debate: Was it a viable monetary system? Was it a de- sirable system? In our model, the (exogenous and stochastic) amount of each metal can be split between monetary uses to satisfy a cash-in-advance constraint, and nonmonetary uses in which the stock of un- coined metal yields utility. The ratio of the monies in the cash-in-advance constraint is endogenous. Bi- metallism is feasible: we find a continuum of steady states (in the certainty case) indexed by the constant exchange rate of the monies; we also prove existence for a range of fixed exchange rates in the stochastic version. Bimetallism does not appear desirable on a welfare basis: among steady states, we prove that welfare under monometallism is higher than under any bimetallic equilibrium. We compute welfare and the variance of the price level under a variety of regimes (bimetallism, monometallism with and without trade money) and find that bimetallism can significantly stabilize the price level, depending on the covari- ance between the shocks to the supplies of metals. Keywords: bimetallism, monometallism, double standard, commodity money *Velde, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago; Weber, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and University of Minne- sota. We thank without implicating Marc Flandreau, Ed Green, Angela Redish, and Tom Sargent. The views ex- pressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Fed- eral Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, or the Federal Reserve System. -

Virtual Currencies in the Eurosystem: Challenges Ahead

STUDY Requested by the ECON committee Virtual currencies in the Eurosystem: challenges ahead Monetary Dialogue July 2018 Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies Authors: Rosa María LASTRA, Jason Grant ALLEN Directorate-General for Internal Policies EN PE 619.020 – July 2018 Virtual currencies in the Eurosystem: challenges ahead Monetary Dialogue July 2018 Abstract Speculation on Bitcoin, the evolution of money in the digital age, and the underlying blockchain technology are attracting growing interest. In the context of the Eurosystem, this briefing paper analyses the legal nature of privately issued virtual currencies (VCs), the implications of VCs for central bank’s monetary policy and monopoly of note issue, and the risks for the financial system at large. The paper also considers some of the proposals concerning central bank issued virtual currencies. This document was provided by Policy Department A at the request of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs. AUTHORS Rosa María LASTRA, Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London Jason Grant ALLEN, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Centre for British Studies, University of New South Wales Centre for Law Markets and Regulation ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE Dario PATERNOSTER EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Janetta CUJKOVA LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees -

Free Silver"; Montana's Political Dream of Economic Prosperity, 1864-1900

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1969 "Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900 James Daniel Harrington The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Harrington, James Daniel, ""Free silver"; Montana's political dream of economic prosperity, 1864-1900" (1969). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1418. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1418 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "FREE SILVER MONTANA'S POLITICAL DREAM OF ECONOMIC PROSPERITY: 1864-19 00 By James D. Harrington B. A. Carroll College, 1961 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1969 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners . /d . Date UMI Number: EP36155 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Disaartation Publishing UMI EP36155 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Complementary Currencies: Mutual Credit Currency Systems and the Challenge of Globalization

Complementary Currencies: Mutual Credit Currency Systems and the Challenge of Globalization Clare Lascelles1 Abstract Complementary currencies—currencies operating alongside the official currency—have taken many forms throughout the last century or so. While their existence has a rich history, complementary currencies are increasingly viewed as anachronistic in a world where the forces of globalization promote further integration between economies and societies. Even so, towns across the globe have recently witnessed the introduction of complementary currencies in their region, which connotes a renewed emphasis on local identity. This paper explores the rationale behind the modern-day adoption of complementary currencies in a globalized system. I. Introduction Coined money has two sides: heads and tails. ‘Heads’ represents the state authority that issued the coin, while ‘tails’ displays the value of the coin as a medium of exchange. This duality—the “product of social organization both from the top down (‘states’) and from the bottom up (‘markets’)”—reveals the coin as “both a token of authority and a commodity with a price” (Hart, 1986). Yet, even as side ‘heads’ reminds us of the central authority that underwrote the coin, currency can exist outside state control. Indeed, as globalization exerts pressure toward financial integration, complementary currencies—currencies existing alongside the official currency—have become common in small towns and regions. This paper examines the rationale behind complementary currencies, with a focus on mutual credit currency, and concludes that the modern-day adoption of complementary currencies can be attributed to the depersonalizing force of globalization. II. Literature Review Money is certainly not a topic unstudied. -

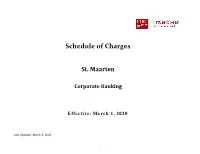

St. Maarten Corporate

Schedule of Charges St. Maarten Corporate Banking Effective: March 1, 2020 Last Updated: March 1, 2020 1 Schedule of Charges CONTENTS 1 CORPORATE DEPOSIT AND TRANSACTION ACCOUNTS - LOCAL CURRENCY 2 CORPORATE DEPOSIT AND TRANSACTION ACCOUNTS - FOREIGN CURRENCY 3 SUNDRY SERVICES 4 LENDING AND CARD SERVICES 5 CORPORATE SERVICES 6 TRADE SERVICES 2 Schedule of Charges CORPORATE DEPOSIT AND TRANSACTION ACCOUNTS - LOCAL CURRENCY Business Current Accounts Call Accounts Minimum monthly service fee $12.50 Minimum monthly service fee $12.50 Withdrawals / Cheques per entry $1.75 Withdrawals / Debits per entry 1 free, thereafter $1.00 Deposits / Credits per entry $1.25 Deposits / Credits per entry 1 free, thereafter $1.00 Business Premium Accounts Fixed Deposit Accounts Minimum monthly service fee $12.50 Transfer to another internal account on maturity No Charge Withdrawals / Cheques per entry 1 free, thereafter $2.00 Transfer to another institution on maturity Draft or Wire Fee Deposits / Credits per entry 1 free, thereafter $2.00 Notes: 1. * - Product/Service Not offered to new clients 2. All figures are quoted in Netherlands Antillean Guilder unless otherwise stated. 3 Schedule of Charges CORPORATE DEPOSIT AND TRANSACTION ACCOUNTS - FOREIGN CURRENCY UNITED STATES DOLLARS (USD) EURO DOLLARS (EUR$) USD Chequing Accounts EUR Business Current Accounts Minimum monthly service fee USD $10.00 Minimum monthly service fee € 10.00 Withdrawals / Cheques per entry 2 free, thereafter USD $0.75 Withdrawals / Cheques per entry 2 free, thereafter €1.00 Deposits / Credits per entry 2 free, thereafter USD $0.75 Deposits / Credits per entry 2 free, thereafter €1.00 USD Business Premium Accounts EUR Business Call Accounts Minimum monthly service fee USD $5.00 Minimum monthly service fee € 10.00 Withdrawals / Cheques per entry 2 free, thereafter USD $1.00 Withdrawals / Cheques per entry 4 free, thereafter €0.40 Deposits / Credits per entry 2 free, thereafter USD $1.00 Deposits / Credits per entry No Charge EUR deposit charge 0.7% p.a. -

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

Racker News Outlets Spreadsheet.Xlsx

RADIO Station Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Cayuga Radio Group (95.9; 94.1; 95.5; 96.7; 103.7; 99.9; 97.3; 107.7; 96.3; 97.7 FM) Online Form https://cyradiogroup.com/advertise/ WDWN (89.1 FM) Steve Keeler, Telcom Dept. Chairperson (315) 255-1743 x [email protected] WSKG (89.3 FM) Online Form // https://wskg.org/about-us/contact-us/ (607) 729-0100 WXHC (101.5 FM) PSA Email (must be recieved two weeks in advance) [email protected] WPIE -- ESPN Ithaca https://www.espnithaca.com/advertise-with-us/ (107.1 FM; 1160 AM) Stephen Kimball, Business Development Manager [email protected], (607) 533-0057 WICB (91.7 FM) Molli Michalik, Director of Public Relations [email protected], (607) 274-1040 x extension 7 For Programming questions or comments, you can email WITH (90.1 FM) Audience Services [email protected], (607) 330-4373 WVBR (93.5 FM) Trevor Bacchi, WVBR Sales Manager https://www.wvbr.com/advertise, [email protected] WEOS (89.5 FM) Greg Cotterill, Station Manager (315) 781-3456, [email protected] WRFI (88.1 FM) Online Form // https://www.wrfi.org/contact/ (607) 319-5445 DIGITAL News Site Contact Person Email/Website/Phone CNY Central (WSTM) News Desk [email protected], (315) 477-9446 WSYR Events Calendar [email protected] WICZ (Fox 40) News Desk [email protected], (607) 798-0070 WENY Online Form // https://www.weny.com/events#!/ Adversiting: [email protected], (607) 739-3636 WETM James Carl, Digital Media and Operations Manager [email protected], (607) 733-5518 WIVT (Newschannel34) John Scott, Local Sales Manager (607) 771-3434 ex.1704 WBNG Jennifer Volpe, Account Executive [email protected], (607) 584-7215 www.syracuse.com/ Online Form // https://www.syracuse.com/placead/ Submit an event: http://myevent.syracuse.com/web/event.php PRINT Newspaper Contact Person Email/Website/Phone Tompkins Weekly Todd Mallinson, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 533-0057 Ithaca Times Jim Bilinski, Advertising Director [email protected], (607) 277-7000 ext.