The Great Gatsby and Norman Mailer’S an American Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

81 Norman Mailer

UDK 821.111(73)–311.6.09Mailer N. NOrMAN MAIlEr - ThE MOST INFlUENTIAl CrITIC OF CONTEMPOrArY rEAlITY IN ThE SECOND hAlF OF ThE TwENTIETh CENTUrY Jasna Potočnik Topler Abstract Norman Mailer, one of the most influential authors of the second half of the twentieth century, faithfully followed his principle that a writer should also be a critic of contemporary reality. Therefore, most of his works portray the reality of the United States of America and the complexities of the contemporary American scene. Mailer described the spirit of his time – from the terror of war and numerous dynamic social and political processes to the 1969 moon landing. Conflicts were often in the centre of his writing, as was the relationship between an individual and the society; he speaks of political power and the dangerous power of capital, while pointing to the threat of totalitarianism in America. Mailer spent his entire career writing about violence, power, perverted sexuality, the phenomenon of Hitler, terrorism, religion and corruption. He continually pointed out that individuals were in constant danger of losing freedom and dignity. keywords: American novel, political power, Norman Mailer, literary journalism Norman Kingsley Mailer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and journalist, and one of the most influential authors of the second half of the twentieth century, faithfully followed his principle that a writer should also be a critic of contemporary reality. One of his biogra- phers Mary V. Dearborn wrote, »In the case of Norman Mailer, the man and his life are of equal, often competing stature with his work, and it is for his life as well as his work that he will be remembered« (Dearborn 8). -

Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Mailer, Norman Title: Norman Mailer Papers Dates: 1919-2005 Extent: 957 document boxes, 44 oversize boxes, 47 galley files (gf), 14 note card boxes, 1 oversize file drawer (osf) (420 linear feet) Abstract: Handwritten and typed manuscripts, galley proofs, screenplays, correspondence, research materials and notes, legal, business, and financial records, photographs, audio and video recordings, books, magazines, clippings, scrapbooks, electronic records, drawings, and awards document the life, work, and family of Norman Mailer from the early 1900s to 2005. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Language: English Access: Open for research with the exception of some restricted materials. Current financial records and records of active telephone numbers and email addresses for Mailer's children and his wife Norris Church Mailer remain closed. Social Security numbers, medical records, and educational records for all living individuals are also restricted. When possible, documents containing restricted information have been replaced with redacted photocopies. Administrative Information Provenance Early in his career, Mailer typed his own works and handled his correspondence with the help of his sister, Barbara. After the publication of The Deer Park in 1955, he began to rely on hired typists and secretaries to assist with his growing output of works and letters. Among the women who worked for Mailer over the years, Anne Barry, Madeline Belkin, Suzanne Nye, Sandra Charlebois Smith, Carolyn Mason, and Molly Cook particularly influenced the organization and arrangement of his records. The genesis of the Mailer archive was in 1968 when Mailer's mother, Mailer, Norman Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Fanny Schneider Mailer, and his friend and biographer, Dr. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

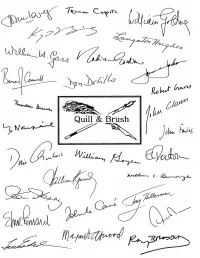

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Personal Frameworks and Subjective Truth: New Journalism and the 1972 U.S

PERSONAL FRAMEWORKS AND SUBJECTIVE TRUTH: NEW JOURNALISM AND THE 1972 U.S. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION BY ASHLEE AMANDA NELSON A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2017 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the reportage of the New Journalists who covered the United States 1972 presidential campaign. Nineteen seventy-two was a key year in the development of New Journalism, marking a peak in output from successful writers, as well as in the critical attention paid to debates about the mode. Nineteen seventy-two was also an important year in the development of campaign journalism, a system which only occurred every four years and had not changed significantly since the time of Theodore Roosevelt. The system was not equipped to deal with the socio-political chaos of the time, or the attempts by Richard Nixon at manipulating how the campaign was covered. New Journalism was a mode founded in part on the idea that old methods of journalism needed to change to meet the needs of contemporary society, and in their coverage of the 1972 campaign the New Journalists were able to apply their arguments for change to their campaign reportage. Thus the convergence of the campaign reportage cycle with the peak of New Journalism’s development represents a key moment in the development of both New Journalism and campaign journalism. I use the campaign reportage of Timothy Crouse in The Boys on the Bus, Norman Mailer in St. George and the Godfather, Hunter S. -

John Updike's New America

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-30-2009 Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America Bob Batchelor University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Batchelor, Bob, "Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1845 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America by Bob Batchelor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D Michael Clune, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Larry Z. Leslie, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 30 , 2009 Keywords: Terrorist , Symbolic Interactionism, literature, novelist, textual analysis © Copyright 2009, Bob Batchelor Dedication With love, to my wife, Katherine Elizabeth Batchelor, and our daughter, Kassandra Dylan Batchelor. Also, thanks for the ongoing support of my family: Linda and Jon Bowen and Bill Coyle. Table of Contents List of Tables iii Abstract -

John Updike's New America by Bob Batchelor a Dissertation Submitted

Running Toward the Apocalypse: John Updike’s New America by Bob Batchelor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph.D Michael Clune, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Victor Peppard, Ph.D. Larry Z. Leslie, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 30 , 2009 Keywords: Terrorist , Symbolic Interactionism, literature, novelist, textual analysis © Copyright 2009, Bob Batchelor Dedication With love, to my wife, Katherine Elizabeth Batchelor, and our daughter, Kassandra Dylan Batchelor. Also, thanks for the ongoing support of my family: Linda and Jon Bowen and Bill Coyle. Table of Contents List of Tables iii Abstract iv Introduction 1 The Writer as Symbolic Interactionist 9 Updike as Experimental Novelist 18 Chapter One—Why Write: Updike as Craftsman, Professional, and Celebrity 29 The Craftsman 36 A Professional Writer 40 Celebrity in a Celebrity-Obsessed Age 42 Selfless as a Lens 50 Chapter Two—Racing Toward the Apocalypse: Terrorist and Updike’s New America 53 Pieces of Updike’s New America 59 Faith and Authenticity 60 Consumerism as a New Religion 66 Race 68 Popular Culture 72 Authority 75 Coming of Age and Sexuality 78 Updike’s New America 83 Chapter Three—Literary Technique in Terrorist 86 Voice and Tone 91 The Lovable Terrorist 95 Narrative Forms 97 Inner Voice 99 Implied Author as Editorialist 103 Dialogue 106 Language 109 Updike as Stylist 113 i Chapter Four—Updike’s Audience 116 Updike and Editors 120 Updike’s Public/Public’s Updike 127 Interrogating 9/11 and Selling Terror 131 Reception of Terrorist 137 Reviews 141 Conclusion – Evolution of a Literary Lion 153 Works Cited 162 About the Author End Page ii List of Tables Table 1 A Sampling of United States Newspapers with Terrorist Review Date and Key Remarks. -

Contributors

Contributors Mashey Bernstein holds a PhD in American Literature from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he currently teaches in the Writing Program and in the Film and Media Studies Department. He has written extensively on Mailer in The Mailer Review, Studies in American-Jewish Literature, the San Francisco Review of Books, and the London Jewish Chronicle. He also writes on film, especially Jewish aspects of the media. Scott Duguid is in the process of completing his Doctoral Thesis on Norman Mailer and the aesthetics/politics of the avant-garde at the University of Edinburgh. His interests include twentieth-century fic- tion, with a particular focus on America; intersections between liter- ature and art history; theories of modernism and postmodernism. He has published articles on Norman Mailer, and on Warhol’s films. Jason Epstein was Editorial Director at Random House for forty years, where he developed the Vintage paperbacks series and pub- lished Norman Mailer, Vladimir Nabokov, E.L. Doctorow, Gore Vidal, Philip Roth, Elaine Pagels, and Richard Holbrook. In 1952 he created the Anchor Books imprint; in 1963 he cofounded the New York Review of Books, and in 1979 he became one of the cofounders of the Library of America, which was intended to market archival quality editions of American classic literature. The first volumes were published in 1982, and the company now prints about 250,000 vol- umes per year. Epstein is the first winner of the National Book Award for Distinguished Service to American Letters (1988) and, in 2007, he has won the Philolexian Award for Distinguished Literary Achievement. -

Stelios Patsiokas ’75

FALL Out of This World Stelios Patsiokas ’75 INSIDE: PHOTOS OF THE NEW LAWRENCE AND SALLY COHEN SCIENCE CENTER president’s letter VOLUME ¡ | ISSUE FALL WILKES MAGAZINE University President The Unique College Experience Dr. Patrick F. Leahy Vice President for Advancement That Denes Wilkes Michael Wood Executive Editor he start of the 2013-2014 academic year—my second year as Wilkes Jack Chielli M.A.’08 Managing Editor president—began with an occasion to honor the past while moving Kim Bower-Spence forward into an exciting future. We named the University archives in honor Editor of Harold Cox, professor emeritus of history and Wilkes’ archivist. It was Vicki Mayk MFA’13 appropriate to start the year recognizing an individual who has been part of Creative Services Lisa Reynolds Wilkes for a half century and who has preserved precious artifacts from our history. T Web Services It was Dr. Cox who first shared with me the idea that Wilkes is an institution Craig Thomas MBA’11 truly unique in American higher education. It was formed to answer an Electronic Communications educational need in the city of Wilkes-Barre and, through many challenges, has Joshua Bonner grown and prospered, even when circumstances might have suggested it would Graduate Assistant Bill Schneider, M.A.’13 not survive. Wilkes continues to occupy a unique place today, a University with Francisco Tutella an academic and co-curricular program mix of a larger research institution in Intern the intimate setting of a smaller liberal arts college. That mix makes for the Christine Lee one-of-a-kind college experience that we know as a Wilkes education. -

Proquest Dissertations

u Ottawa L'Universitd canadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES '— FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L,'Universit6 canadierme Canada's university Ashton Howley AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS Ph.D. (English Literature) GRADE/DEGREE Department of English 7Acurifnrc"aE7DE?A^ Mailer Again: Studies in the Late Fiction TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS David Rampton DIRECTEUR (DIRECf RICE) DE LA THESE / THESIS SUPERVISOR EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS J. Michael Lennon David Jarraway Tom Allen Bernhard Radloff Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctoral / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Mailer Again: Studies in the Late Fiction ASHTON HOWLEY Thesis submitted to Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD program in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa ©Ashton Howley Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48399-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48399-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47766-6 — Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie Mckinley Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47766-6 — Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie McKinley Index More Information Index Abbott, Jack Henry, –, –, , , , Beauvoir, Simone de, , , , –, –, Beckett, Samuel, , Abernathy, Ralph, Bellow, Saul, , , , , Acker, Kathy, Bentley, Beverly, , Advertisements for Myself, , –, , , , Beyle, Marie-Henri. See Stendhal , , –, , , , , , , Beyond the Law (film), , – –, , , , , , , Big Empty, The, , , , , , –, Black Arts Movement, Agee, James, Black Power Movement, , –, Aldridge, John, , Bly, Robert, , Ali, Muhammad, , , , , , , , Bowles, Paul, – , , , –, –, See also Brando, Marlon, , , The Fight Breslin, Jimmy, American Dream, An, , , , , , , Brooklyn, , , , , , , –, , , –, , , , Brosnan, Jim, –, , , –, –, Buchanan, Patrick, , –, , , , , Buckley, William F., –, , , –, –, –, , Bullfight: A Photographic Narrative with Text,, –, –, , , , Burke, Edmund, , – Burroughs, William, , –, , , Ancient Evenings, , , –, , , , , – –, , , , Bush, George W., , – Armies of the Night, The, –, , , , , , , –, , , , –, Calculus at Heaven, A, , –, , –, –, Campbell, Jeanne, , –, , , , , , Cannibals and Christians, , –, , , , –, –, , , , , , , – Capote, Truman, , , , , , , , Arnold, Matthew, , Aronowitz, Al, Castle in the Forest, The, , , , –, , , , – Baker, Nicole, , –, , – Castro, Fidel, , , – Baldwin, James, , , , , , , , Cavett, Dick, –, , , , , , Ceballos, Jacqueline, , Baraka, Amiri, –, Cheever, John, Barbary Shore, , , , , , , –, Civil Defense Protest Committee, , –, , , , , Civil Rights -

Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie Mckinley Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47766-6 — Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie McKinley Frontmatter More Information NORMAN MAILER IN CONTEXT This volume offers new insight into the breadth of contexts that inform Norman Mailer’s body of work. It examines important liter- ary, critical, theoretical, cultural, and historical frameworks for Mailer’s writing, highlighting the ways his work reflects the concerns of twentieth and twenty-first century America. This book traces Mailer’s literary influences; his contributions to a variety of literary genres; his participation in the American political sphere; the philo- sophical, religious, and gendered contexts that shape his work; and the iconic American figures he profiled. The book concludes with reflections on Mailer’s literary and cultural legacy, emphasizing his advocacy for literary freedom and the contemporary resonance of his work. is Associate Professor of English at Harper College. She is the author of Masculinity and the Paradox of Violence in American Fiction () and Understanding Norman Mailer (), and currently serves as the president of the Norman Mailer Society. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47766-6 — Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie McKinley Frontmatter More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47766-6 — Norman Mailer in Context Edited by Maggie McKinley Frontmatter More Information NORMAN MAILER IN CONTEXT MAGGIE -

Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Mailer, Norman Title: Norman Mailer Papers Dates: 1919-2005 Extent: 957 document boxes, 44 oversize boxes, 47 galley files (gf), 14 note card boxes, 1 oversize file drawer (osf) (420 linear feet) Abstract: Handwritten and typed manuscripts, galley proofs, screenplays, correspondence, research materials and notes, legal, business, and financial records, photographs, audio and video recordings, books, magazines, clippings, scrapbooks, electronic records, drawings, and awards document the life, work, and family of Norman Mailer from the early 1900s to 2005. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Language: English Access: Open for research with the exception of some restricted materials. Current financial records and records of active telephone numbers and email addresses for Mailer's children and his wife Norris Church Mailer remain closed. Social Security numbers, medical records, and educational records for all living individuals are also restricted. When possible, documents containing restricted information have been replaced with redacted photocopies. Administrative Information Provenance Early in his career, Mailer typed his own works and handled his correspondence with the help of his sister, Barbara. After the publication of The Deer Park in 1955, he began to rely on hired typists and secretaries to assist with his growing output of works and letters. Among the women who worked for Mailer over the years, Anne Barry, Madeline Belkin, Suzanne Nye, Sandra Charlebois Smith, Carolyn Mason, and Molly Cook particularly influenced the organization and arrangement of his records. The genesis of the Mailer archive was in 1968 when Mailer's mother, Fanny Schneider Mailer, Norman Manuscript Collection MS-2643 Mailer, and his friend and biographer, Dr.