Sustaining Success: a Case Study of Effective Practices in Fairfield HVA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selective High School 2021 Application

Stages of the placement process High Performing Students Team Parents read the application information online From mid-September 2019 Education Parents register, receive a password, log in, and then completeApplying and submit for the application Year online7 entry From 8 to selective high schools October 2019 to 11 November 2019 Parents request any disability provisions from 8 October to in 11 November 2019 2021 Principals provide school assessment scores From 19 November to Thinking7 December 2019 of applying for Key Dates Parents sent ‘Test authority’ letter On 27 Febru- ary 2020 a government selective Application website opens: Students sit the Selective High School 8 October 2019 Placementhigh Test forschool entry to Year 7for in 2021 Year On 12 7 March 2020 Any illness/misadventurein 2021?requests are submitted Application website closes: By 26 March 2020 10 pm, 11 November 2019 You must apply before this deadline. Last dayYou to change must selective apply high school online choices at: 26 April 2020 School selectioneducation.nsw.gov.au/public- committees meet In May and Test authority advice sent to all applicants: June 2020 27 February 2020 Placementschools/selective-high-schools- outcome sent to parents Overnight on 4 July and-opportunity-classes/year-7 Selective High School placement test: 2020 12 March 2020 Parents submit any appeals to principals By 22 July 2020 12 Parents accept or decline offers From Placement outcome information sent overnight on: July 2020 to at least the end of Term 1 2021 4 July 2020 13 Students who have accepted offers are with- drawn from reserve lists At 3 pm on 16 December 2020 14 Parents of successful students receive ‘Author- Please read this booklet carefully before applying. -

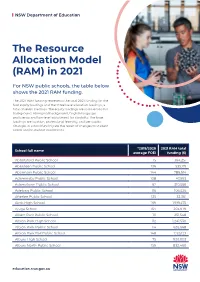

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

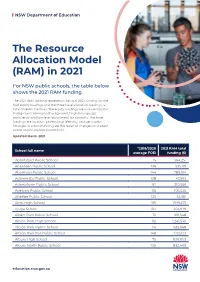

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

2019-Annual-Report.Pdf

Annual Report 2017– 18 Annual Report 2018-19 We Give Life-Changing Scholarships Contents Our Impact 2 Chair Report 3 Executive Director Report 4 Awards Night 5 2019 Public Education Foundation The Public Education Foundation Scholarship Recipients 6 Our student is a charity dedicated to scholarships address providing life-changing 2018 Minister’s and Secretary’s factors contributing to scholarships to young people in Awards for Excellence 10 What we do disadvantage: public education, their teachers and principals. Scholar Profiles 12 The Foundation is supported Students from low Our People 14 by the NSW Department socio-economic of Education and works in backgrounds collaboration with schools, Monitoring and Evaluation 15 Support communities, the private sector students who face social and economic and the government to help 2018 – 2019 Financial Report 16 disadvantage to achieve their full potential Indigenous students students achieve their full through life-changing scholarships. potential at a public school, Board of Directors 20 while enhancing the value and reputation of public school Donors and Supporters 21 education. Provide Students from professional development opportunities to refugee backgrounds educators and school leaders to enable them to To find out more about our work extend their leadership and teaching skills. please visit our website: Students in rural and remote areas Enhance www.publiceducationfoundation.org.au the value and reputation of Australia’s public schools, ensuring every Australian has access Students living with a to a high-quality, inclusive education. disability ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 1 Our Chair Report Impact WHAT OUR SCHOLARS SAY ... "Thank you for all your support, you definitely have WE HAVE GIVEN made a difference in my life." from early 2009 At the end of my first year as Chair of the Public Education to the end of June 2019 Foundation, I am delighted to be reporting on another successful year. -

NSW Equity Consortium

NSW Equity Consortium Whole-of-cohort outreach with Years 7–9 Quick overview Approach What do we mean by literacy? • Alliance between UNSW, UTS and Macquarie University and partner Literacy is more than the teaching of ‘basic skills’, although there is space for these as the ‘building blocks’ schools of literacy development. We view literacy as a set of practices that are deeply context-dependent, and are connected to the event, practices, audiences and distinct epistemologies of a subject. We are also • Research-informed literacy intervention outreach program all advocates for a view of critical literacy as underpinning this project, as this will permit a social justice- • 7–9 whole cohort approach orientation (as per Freirean notions of reading the word, reading the world) to the teaching and learning of • Designed and delivered in partnership with three universities and literacy. By this we mean that it is useful to see literacy as a continuum, from a focus on the fundamentals partner schools (spelling, phonics, grammar) at one end to the socio-political and ethico-civic potentials of literacy (reading • 5-year commitment between the lines, asking critical questions, making connections across texts, supporting intellectual risk- taking) at the other. The focus on literacy is both informed by strong consensus in the literature about the fundamental role played by literacy in student attainment, and a request from the school partners. In particular, while the research predominantly focuses on student writing, there is a strong warrant to focus on students’ Program purpose and focus: reading practices, particularly with regard to interpretive and inferential comprehension. -

Unsw School Mathematics Competition 1996

Parabola Volume 32, Issue 2 (1996) UNSW SCHOOL MATHEMATICS COMPETITION 1996 LIST OF PRIZEWINNERS SENIOR DIVISION Equal first prize MAH Alexandre, North Sydney Boys’ High School. STITT Daniel Ian, Sydney Grammar School. Third prize YAO Andrew, Gosford High School. Eleven prizes of $60 HARVEY David Michael, Sydney Boys’ High School. SCERRI Brian James, Canberra Grammar School. PHILP David James, Caringbah High School. YEOH Lee, Trinity Grammar School. JENKINS Martin David, Beacon Hill High School. NG Gordon, Sydney Grammar School. TUNG Andrew, Sydney Grammar School. KUSILEK Jonathan, Hurlstone Agricultural High School. HO Jurn, James Ruse Agricultural High School. SEKERS David, Moriah College. WONG Johnny Ho Yin, Sydney Boys’ High. Eight prizes of $40 WONG Adrian, James Ruse Agricultural High School. LAM Thomas Fun Yau, Sydney Grammar School. CHAN Kenny, Sydney Boys’ High School. CHEN Chang, Newcastle Grammar School. GOODMAN Paul Jeffrey, Sydney Grammar School. MORRISON Scott, Sydney Grammar School. LAI Rosalyn, Pymble Ladies’ College. GOODWIN Andrew, Sydney Boys’ High School. Forty one certificates JEYASINGAM Neil Raveen, Sydney Grammar School. CHAPMAN Matthew, Knox Grammar School. WONG Emily, North Sydney Girls’ High School. 1 CHEETHAM James Howard, Hurlstone Agricultural High School. LANCKEN Brad, Knox Grammar School. KONG Justin, Sydney Grammar School. LAN Ronny, Knox Grammar School. BAYLISS Richard, Barker College. MCDOUGALL Hamish, Knox Grammar School. EISENBERG Naomi, Moriah College. LUK Bernard Hwai-Yih, James Ruse Agricultural High School. WONG Christopher, Newington College. HACHROTH Adam Michael, Cranbrook School. BLAIR Nicholas, Cranbrook School. MAY David Malcolm, James Ruse Agricultural High School. EMMETT James Stuart, Sydney Grammar School. KAM Kathy, Pymble Ladies’ College. BROADHEAD Christine, Monaro High School. -

Spring Edition – No: 48

Spring Edition – No: 48 2015 Commonwealth Vocational Education Scholarship 2015. I was awarded with the Premier Teaching Scholarship in Vocational Education and Training for 2015. The purpose of this study tour is to analyse and compare the Vocational Education and Training (Agriculture/Horticulture/Primary Industries) programs offered to school students in the USA in comparison to Australia and how these articulate or prepare students for post school vocational education and training. I will be travelling to the USA in January 2016 for five weeks. While there, I will visit schools, farms and also attend the Colorado Agriculture Teachers Conference on 29-30th January 2016. I am happy to send a detailed report of my experiences and share what I gained during this study tour with all Agriculture teachers out there. On the 29th of August I went to Sydney Parliament house where I was presented with an award by the Minister of Education Adrian Piccoli. Thanks Charlie James President: Justin Connors Manilla Central School Wilga Avenue Manilla NSW 2346 02 6785 1185 www.nswaat.org.au [email protected] ABN Number: 81 639 285 642 Secretary: Carl Chirgwin Griffith High School Coolah St, Griffith NSW 2680 02 6962 1711 [email protected]. au Treasurer: Membership List 2 Graham Quintal Great Plant Resources 6 16 Finlay Ave Beecroft NSW 2119 NSWAAT Spring Muster 7 0422 061 477 National Conference Info 9 [email protected] Articles 13 Technology & Communication: Valuable Info & Resources 17 Ian Baird Young NSW Upcoming Agricultural -

NSWCHS - PUMA Football Cup & Trophy

The NSWCHS - PUMA Football Cup & Trophy 2018 Knock Out Football Team Information Est. 1889 NSWCHS ‐ PUMA Football Cup & Trophy . The PUMA Cup for boys . The PUMA Trophy for girls The Annual Knockout Football Competitions for New South Wales State High Schools RESULTS Results must be telephoned and/or emailed, by the winning school, to either the State KO Convener or to the respective Regional Convener, or the Sports High Co‐ordinator as indicated on the draw, immediately following the match. A written confirmation is to be forwarded within three school days. Failure to notify results may lead to the disqualification of the winning school. Your co‐operation is also sought in despatching the MEDIA/INTERNET REPORT to the Media Officer within TWO school days (Team photographs as jpg. attachments can also be forwarded). These will be publicised on the NSW Schools Football website. BOYS AND GIRLS FINAL SERIES DRAW 1. The draw for the Final Series will be conducted as a separate Statewide Regional ‐ Comprehensive High Schools Competition and Sports High School Competition with boys and girls divisions. 2. The 2018 PUMA Sports High School Football Competition will be played as a round robin & with a final for the 1st & 2nd positions, as indicated below: Please note the first mentioned team is the home team in all rounds. All other knockout home and away rules apply. Sports High School play by dates may vary to the PUMA Comprehensive High School schedule and played as gala days with each Sports High School hosting a round of competition. 2018 BOYS and GIRLS Sports High Schools DRAW: (i) Kick Off Times: Girls 10.00am Boys 11.30am (ii) The Home Team is the first mentioned team in the draw. -

Participating Schools List

PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS LIST current at Saturday 11 June 2016 School / Ensemble Suburb Post Code Albion Park High School Albion Park 2527 Albury High School* Albury 2640 Albury North Public School* Albury 2640 Albury Public School* Albury 2640 Alexandria Park Community School* Alexandria 2015 Annandale North Public School* Annandale 2038 Annandale Public School* Annandale 2038 Armidale City Public School Armidale 2350 Armidale High School* Armidale 2350 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Killarney Beacon Hill 2100 Arts Alive Combined Schools Choir Pennant Hills Pennant Hills 2120 Ashbury Public School Ashbury 2193 Ashfield Boys High School Ashfield 2131 Asquith Girls High School Asquith 2077 Avalon Public School Avalon Beach 2107 Balgowlah Heights Public School* Balgowlah 2093 Balgowlah North Public School Balgowlah North 2093 Balranald Central School Balranald 2715 Bangor Public School Bangor 2234 Banksmeadow Public School* Botany 2019 Bathurst Public School Bathurst 2795 Baulkham Hills North Public School Baulkham Hills 2153 Beacon Hill Public School* Beacon Hill 2100 Beckom Public School Beckom 2665 Bellevue Hill Public School Bellevue Hill 2023 Bemboka Public School Bemboka 2550 Ben Venue Public School Armidale 2350 Berinba Public School Yass 2582 Bexley North Public School* Bexley 2207 Bilgola Plateau Public School Bilgola Plateau 2107 Billabong High School* Culcairn 2660 Birchgrove Public School Balmain 2041 Blairmount Public School Blairmount 2559 Blakehurst High School Blakehurst 2221 Blaxland High School Blaxland 2774 Bletchington -

2019 Higher School Certificate- Illness/Misadventure Appeals

2019 Higher School Certificate- Illness/Misadventure Appeals Number of Number of HSC Number of Number of Number of Number of HSC Number of HSC Number of Number of HSC students student exam student exam student exam applied courses School Name Locality student exam student exam course mark exam students lodging I/M courses applied components components fully or partially courses components changes applications for applied for upheld upheld Abbotsleigh WAHROONGA 164 7 922 1266 25 31 31 25 17 Airds High School CAMPBELLTOWN 64 3 145 242 9 16 12 6 6 Al Amanah College LIVERPOOL Al Noori Muslim School GREENACRE 91 9 377 447 15 17 17 15 12 Al Sadiq College GREENACRE 41 5 212 284 9 10 10 9 4 Albion Park High School ALBION PARK 67 2 323 468 2 2 2 2 2 Albury High School ALBURY 105 6 497 680 12 13 13 12 7 Alesco Illawarra WOLLONGONG Alesco Senior College COOKS HILL 53 3 91 94 3 3 3 3 3 Alexandria Park Community School ALEXANDRIA Al-Faisal College AUBURN 114 2 565 703 6 7 7 6 5 Al-Faisal College - Campbelltown MINTO All Saints Catholic Senior College CASULA 219 10 1165 1605 27 32 31 27 14 All Saints College (St Mary's Campus) MAITLAND 204 10 1123 1475 13 15 12 10 7 All Saints Grammar BELMORE 45 2 235 326 3 3 0 0 0 Alpha Omega Senior College AUBURN 113 7 475 570 12 12 11 11 6 Alstonville High School ALSTONVILLE 97 2 461 691 4 5 5 4 2 Ambarvale High School ROSEMEADOW 74 3 290 387 9 11 11 9 6 Amity College, Prestons PRESTONS 159 5 682 883 12 14 14 12 8 Aquinas Catholic College MENAI 137 4 743 967 9 13 13 9 7 Arden Anglican School EPPING 76 9 413 588 -

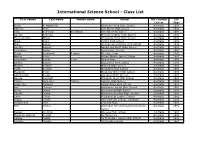

International Science School - Class List

International Science School - Class List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS Cohort Year Reem Al Mahmood Gladstone Park High School Australia 1981 Kathryn Allen Fort Street High School Australia 1981 Jean Anderson Snodgrass Glendale High School Australia 1981 Narelle Andrews Moorefield Girls' High School Australia 1981 Helen Christie Atkins St George Girls' High School Australia 1981 Philip Aubin Kotara High School Australia 1981 Mark Ballico St Andrew's Catholic High School Australia 1981 Geoffry Barnes Bankstown Boys' High School Australia 1981 Jacqueline Baxter Kiama High School Australia 1981 Debra Bernhardt Searles Glendale High Australia 1981 Marlon Binet Hobart Matriculation College Australia 1981 Jacqueline Blanck Cram Bowral High Australia 1981 Shirley Bowen Gloucester High School Australia 1981 Michael Bradley Malvina High School Australia 1981 Scott Bradley Macintyre High School Australia 1981 Elizabeth Bragg Mackellar Girls' HIgh School Australia 1981 David Logan Brown Glenaeon High School Australia 1981 Angela Carabott Elizabeth West High School Australia 1981 Tracey Carpenter Timms Latrobe High School Australia 1981 Lillian Joy Carswell Cairns State High School Australia 1981 Ann Choong Hollywood Senior High School Australia 1981 Helen Chriss Queenwood High School Australia 1981 Soo Mi Chung Maroubra Junction High School Australia 1981 Janet Cohen Presbyterian Ladies' College Australia 1981 Robyn Collins Sacred Heart College, Sandgate Australia 1981 Jocelyn Rox Dart Cronulla High Australia 1981 Tom -

An Overview of Stile, Australia's #1 Science Resource Provider

An overview of Stile, Australia’s #1 science resource provider EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR SCHOOL LEADERS Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 2 Table of contents Welcome letter 3 How we are rethinking science education > Our principles 5 > Our pedagogy 7 > Our approach 9 A simple solution > Stile Classroom 12 > Squiz 14 > Professional learning 15 > Stile Concierge 16 Key benefits 17 The Stile community of schools 19 The rest is easy 24 Stile | Executive summary for school leaders 3 It’s time to rethink science at school I’m continuously awestruck by the sheer power of science. In a mere 500 years, a tiny fraction of humanity’s long history, science – and the technological advances that have stemmed from it – has completely transformed every part of our lives. The scale of humanity’s scientific transformation in such a short period is so immense it’s hard to grasp. My grandmother was alive when one of the world’s oldest airlines, Qantas, was born. In her lifetime, flight has become as routine as daily roll call. Disease, famine and the toll of manual labour that once ravaged the world’s population have also been dramatically reduced. Science is at the heart of this progress. Given such incredible advancement, it’s tempting to think that science education must be in pretty good shape. Sadly, it isn’t. We could talk about falling PISA rankings, or declining STEM enrolments. But instead, and perhaps more importantly, let’s consider the world to which our students will graduate. A world of “fake news” and “alternative facts”.