'Asians Always Do Well': Getting Behind the Stereotypes of 'Ethnic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selective High School 2021 Application

Stages of the placement process High Performing Students Team Parents read the application information online From mid-September 2019 Education Parents register, receive a password, log in, and then completeApplying and submit for the application Year online7 entry From 8 to selective high schools October 2019 to 11 November 2019 Parents request any disability provisions from 8 October to in 11 November 2019 2021 Principals provide school assessment scores From 19 November to Thinking7 December 2019 of applying for Key Dates Parents sent ‘Test authority’ letter On 27 Febru- ary 2020 a government selective Application website opens: Students sit the Selective High School 8 October 2019 Placementhigh Test forschool entry to Year 7for in 2021 Year On 12 7 March 2020 Any illness/misadventurein 2021?requests are submitted Application website closes: By 26 March 2020 10 pm, 11 November 2019 You must apply before this deadline. Last dayYou to change must selective apply high school online choices at: 26 April 2020 School selectioneducation.nsw.gov.au/public- committees meet In May and Test authority advice sent to all applicants: June 2020 27 February 2020 Placementschools/selective-high-schools- outcome sent to parents Overnight on 4 July and-opportunity-classes/year-7 Selective High School placement test: 2020 12 March 2020 Parents submit any appeals to principals By 22 July 2020 12 Parents accept or decline offers From Placement outcome information sent overnight on: July 2020 to at least the end of Term 1 2021 4 July 2020 13 Students who have accepted offers are with- drawn from reserve lists At 3 pm on 16 December 2020 14 Parents of successful students receive ‘Author- Please read this booklet carefully before applying. -

2020 Sydney Girls High School Annual Report

2020 Annual Report Sydney Girls High School 8138 Page 1 of 18 Sydney Girls High School 8138 (2020) Printed on: 28 April, 2021 Introduction The Annual Report for 2020 is provided to the community of Sydney Girls High School as an account of the school's operations and achievements throughout the year. It provides a detailed account of the progress the school has made to provide high quality educational opportunities for all students, as set out in the school plan. It outlines the findings from self-assessment that reflect the impact of key school strategies for improved learning and the benefit to all students from the expenditure of resources, including equity funding. School contact details Sydney Girls High School Moore Park Surry Hills, 2010 www.sydneygirl-h.schools.nsw.edu.au [email protected] 9331 2336 Message from the principal Despite the challenges of 2020 the school continued to deliver high level investment in the lives and learning of all students at Sydney Girls High. Appreciation is due to all staff, parents and student leaders who were significant in maintaining morale and close communication across the months of online learning when the school was operating without a physical presence and we were forced to respond to the ever changing conditions in NSW schools. Out of this extraordinary year emerged some remarkable achievements and a greater sense of appreciation of the value of friendship and collegiality which school life provides for us all. A landmark achievement was the construction of our long awaited building The Governors Centre with Sydney Boys High which throughout the months of the pandemic was able to be progressed with few interruptions to the building schedule. -

Sustaining Success: a Case Study of Effective Practices in Fairfield HVA

OCTOBER 2017 Sustaining Success: A case study of effective practices in Fairfield high value-add schools Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation The Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE), undertakes in-depth analysis of education programs and outcomes across early childhood, school, training and higher education to inform whole-of-government, evidence based decision making. Put simply, it seeks to find out what works best. CESE’s three main responsibilities are to: • provide data analysis, information and evaluation that improve effectiveness, efficiency and accountability of education programs and strategies. • collect essential education data and provide a one-stop shop for information needs – a single access point to education data that has appropriate safeguards to protect data confidentiality and integrity • build capacity across the whole education sector so that everyone can make better use of data and evidence. More information about the Centre can be found at: cese.nsw.gov.au Author Natalie Johnston-Anderson Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation, October 2017, Sydney, NSW For more information about this report, please contact: Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation Department of Education GPO Box 33 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Email: [email protected] Telephone: +61 2 9561 1211 Web: cese.nsw.gov.au Acknowledgements The Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation (CESE) would like to sincerely thank the principals and teaching staff of the schools in this case study for generously sharing their time, perceptions and insights with the researchers. CESE also acknowledges the critical role of Fairfield Network Director, Cathy Brennan, in instigating this work and in celebrating the success of these schools. -

10 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10

Applications Years 8 – 11, 2022 Applications open Monday 21 June 2021 and close Friday 16 July 2021 All enquiries: Please email [email protected] Years 8 – 10 2022 All students applying for Fort Street High School must include the following with their application. 1. Completed Selective Schools Application Form available on the Selective High School website: https://education.nsw.gov.au/public-schools/selective-high-schools-and-opportunity-classes/years-8-to- 12 2. English writing piece of maximum 600 words (handwritten – not typed): Year 8 – 10 2022 Essay Topic (if you are in Year 7,8 or 9 in 2021) “Something good can come out of a crisis. A crisis can bring about a real change and help us re- evaluate our humanity”. (Discuss) 3. A copy of the student’s Birth Certificate or Passport 4. A copy of the Semester 2 - 2020 school report and Semester 1 – 2021 school report (if available) 5. Copies of evidence of recent participation in academic competitions and co-curricular activities 6. All applications must be posted and received before, on or date stamped Friday 16 July 2021. Please do not come to the school. No emailed applications. No late applications will be considered. Postal Address: Fort Street High School – Enrolments, Parramatta Road Petersham NSW 2049 7. There is no entrance test for applicants for Years 8 – 10, 2022 Administration Fee for Years 8 – 10 Applications There is a $50 non-refundable administration fee to cover the processing of the application. Payment can be made by cheque made out to Fort Street High School (to be included with the application) or on our school website: www.fortstreet.nsw.edu.au 1. -

Schools Competition 2014 School Addresses and Contact Details

NSW Junior Chess League METROPOLITAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS COMPETITION 2014 SCHOOL ADDRESSES AND CONTACT DETAILS Abbotsleigh Region: Met North Address: 1666 Pacific Highway (cnr Ada Ave), Wahroonga NSW 2076 Chess Coordinator: Mr P Garside School Phone: 9473 7779 School Fax: 9473 7680 Ascham School Region: Met East Address: 188 New South Head Rd, Edgecliff NSW 2027 Chess Coordinator: Mr A Ferch School Phone: 8356 7000 School Fax: 8356 7230 Asquith Girls High School Region: Met North Address: Stokes Avenue, Asquith NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mr M Borri School Phone: 9477 6411 School Fax: 9482 2524 Australian International Academy - Sydney Campus Region: Met East Address: 420 Liverpool Road, Strathfield NSW 2135 Chess Coordinator: Mr W Zoabi School Phone: 9642 0104 School Fax: 9642 0106 Balgowlah Boys (Northern Beaches Secondary College - Balgowlah Boys Campus) Region: Met North Address: Maretimo Street, Balgowlah NSW 2093 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Hu School Phone: 9949 4200 School Fax: 9907 0266 Barker College Region: Met North Address: 91 Pacific Highway, Hornsby NSW 2077 Chess Coordinator: Mrs G Cunningham School Phone: 9847 8399 School Fax: 9477 3556 Baulkham Hills High School Region: Met West Address: 419A Windsor Road, Baulkham Hills NSW 2153 Chess Coordinator: Mr J Chilwell School Phone: 9639 8699 School Fax: 9639 4999 Blue Mountains Grammar School Region: Met West Address: Matcham Avenue, Wentworth Falls NSW 2782 Chess Coordinator: Mr C Huxley School Phone: 4757 9000 School Fax: 4757 9092 Canterbury Boys High School Region: Met East Address: -

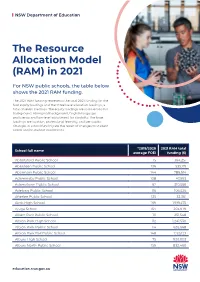

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 347,551 Alma Public -

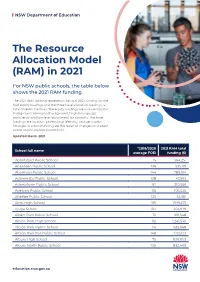

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

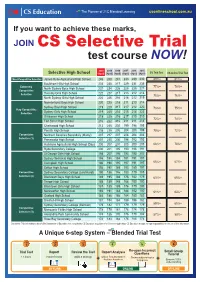

2020 Selective Trial Test Result

The Pioneer of 21C Blended Learning csonlineschool.com.au If you want to achieve these marks, JOIN CS Selective Trial test course NOW! 2020 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Selective High School (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) (April) CS Trial Test CS online Trial Test Most Competitive Selective James Ruse Agricultural High School 246 250 241 243 239 230 80%+ 81%+ Baulkham Hills High School 234 230 217 229 231 235 Extremely 77%+ 78%+ North Sydney Boys High School 231 234 226 225 225 221 Competitive Hornsby Girls High School 222 227 217 213 212 216 Selective 75%+ 76%+ North Sydney Girls High School 222 226 216 216 212 219 Normanhurst Boys High School 220 225 218 211 210 214 Sydney Boys High School 219 229 217 217 212 220 Very Competitive 73%+ 75%+ Sydney Girls High School 219 225 216 215 214 223 Selective Girraween High School 218 225 216 217 210 210 72%+ 74%+ Fort Street High School 216 222 215 211 211 216 Chatswood High School 213 215 202 199 198 198 Penrith High School 208 215 205 204 200 199 70%+ 72%+ Competitive Northern Beaches Secondary (Manly) 207 217 207 206 204 206 Selective (1) Parramatta High School 201 210 200 194 192 193 Hurlstone Agricultural High School (Day) 200 207 201 203 200 205 68%+ 70%+ Ryde Secondary College 200 201 195 190 186 191 St George Girls High School 198 207 195 195 195 202 Sydney Technical High School 198 198 194 191 191 197 Caringbah High School 196 198 195 197 191 197 65%+ 67%+ Sefton High School 192 197 189 193 189 197 Competitive Sydney Secondary College (Leichhardt) 190 186 186 183 179 185 Selective -

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents

Northern Sydney District Data Profile Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, Northern Sydney Contents Introduction 4 Demographic Data 7 Population – Northern Sydney 7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population 10 Country of birth 12 Languages spoken at home 14 Migration Stream 17 Children and Young People 18 Government schools 18 Early childhood development 28 Vulnerable children and young people 34 Contact with child protection services 37 Economic Environment 38 Education 38 Employment 40 Income 41 Socio-economic advantage and disadvantage 43 Social Environment 45 Community safety and crime 45 2 Contents Maternal Health 50 Teenage pregnancy 50 Smoking during pregnancy 51 Australian Mothers Index 52 Disability 54 Need for assistance with core activities 54 Housing 55 Households 55 Tenure types 56 Housing affordability 57 Social housing 59 3 Contents Introduction This document presents a brief data profile for the Northern Sydney district. It contains a series of tables and graphs that show the characteristics of persons, families and communities. It includes demographic, housing, child development, community safety and child protection information. Where possible, we present this information at the local government area (LGA) level. In the Northern Sydney district there are nine LGAS: • Hornsby • Hunters Hill • Ku-ring-gai • Lane Cove • Mosman • North Sydney • Northern Beaches • Ryde • Willoughby The data presented in this document is from a number of different sources, including: • Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) • Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) • NSW Health Stats • Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC) • NSW Government administrative data. 4 Northern Sydney District Data Profile The majority of these sources are publicly available. We have provided source statements for each table and graph. -

THE RECORD 2007 the Record 2007

THE SYDNEY HIGH SCHOOL THE RECORD 2007 THE RECORD VOL. XCVII 2007 The Record 2007 The Journal of Sydney Boys High School Moore Park, Surry Hills NSW 2010 Volume XCVII Sydney Boys High School The Record 2007 1 2 The Record 2007 Sydney Boys High School Table of Contents Staff Directory . 5 Welfare, Leadership and Community Services .81 Editor’s Comments . 8 Boggabilla Trip . 88 Outstanding Academic Achievement . 9 International Computer Skills Competition . 89 Year 12 Farewell Assembly . 11 Tournament of the Minds . 89 Year 12 Farewell: Captain’s Address . 13 Da Vinci Decathlon . 90 Speech Night Address . 15 The Visual Arts . 94 Annual Prize Giving Awards . 18 Music . 117 Vale Phillip Day . 29 Chess . .126 ANZAC Day . 31 Debating . 127 Remembrance Day . 33 Representatives . 136 Annual Prize Giving Awards . 18 Summer Sport . 137 Salvete . 34 Cricket . 139 Valete . 36 Basketball . 157 Class Lists . 51 Tennis . 181 Cadet Unit . 57 Rowing . 188 P & C Report . 61 Basketball . 105 Canteen . 62 Swimming . 209 Ski Trip . 62 Sailing . 213 Old Boys Union . 63 Winter Sport . 215 Foundation Day Address . 64 Athletics . 216 Duke of Edinburgh Award . 66 Rugby . 227 Library Report . 68 Football . 240 English . 70 Cross Country . 259 Mathematics . 77 Rifle Shooting . 262 Titration . 79 Fencing . 264 Science . 80 Volleyball . 267 Geography . 80 List of Officers . 271 Sydney Boys High School The Record 2007 3 4 The Record2007 Staff Sydney BoysHigh School Staff 2007 Back Row: S.Storey, G.Moody, C.Kesting, P.Ganderton. Fifth Row: B.Hayman, A.Fuller, R.Boros, H.Howey, B.Branigan, S.Codey, T.Dolan, R.Farrington. -

Youth Work in North Sydney – 2018 Year in Review

ITEM CLS05 REPORTS 10/12/18 NORTH SYDNEY COUNCIL REPORTS Report to General Manager Attachments: Nil SUBJECT: Youth Work in North Sydney – 2018 Year in Review AUTHOR: Greg Nikoletos, Youth Services and Partnerships Coordinator ENDORSED BY: Martin Ellis, Director Community and Library Services EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This report provides a summary of the outcomes for the Youth Work team for 2018. Young people were engaged primarily through Council’s Youth Centre, Planet X, but also in partnerships, and other venues, with other key stakeholders in the community. The Youth Workers engaged with a broad spectrum of local young people, a subset of whom presented with multiple risk factors. The year’s programs are briefly described, illustrating the range of opportunities Council with its partners provides to young people in need. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS: Youth Services annual costs amount to $264,000 with some $20,000 operational support contributed by the NSW government. RECOMMENDATION: 1. THAT the report be received. Report of Greg Nikoletos, Youth Services and Partnerships Coordinator Re: Youth Work in North Sydney – 2018 Year in Review (2) LINK TO COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN The relationship with the Community Strategic Plan is as follows: Direction: 4. Our Social Vitality Outcome: 4.1 North Sydney is connected, inclusive, healthy and safe BACKGROUND The Youth Work team primarily provides direct service and universal access from Planet X Youth Centre while also engaging in community development with key stakeholders to provide a variety of programs and opportunities for young people. Planet X Youth Centre is based at the Music Shell in St. Leonards Park. It operates as a drop- in centre offering a safe space for young people to visit, socialise, participate in activities and programs, and seek assistance if required. -

H I G H N O T

H The Weekly Newsletter of Sydney Boys High School Vol 20 No 40 13 December 2019 From the Principal Bruce Gordon, High’s ever-reliable team High Notes - last edition for 2019 manager. It is a mammoth job to organise a I This is our final edition of High Notes for 2019. I Nationals campaign year after year. Kevin want to thank all the regular contributors who Fernando(10T) was selected in the Performing keep us all up to date with the many and varied Arts Unit 2020 Drama Company. Well done, achievements of our students at High. Thank Kevin. From the list of HSC Encore you to our editors, Dave Te Rata and Meredith nominations, Yung Kim (11T) performance and Thomas who collate and set out the articles for Kent Gu (11F) composition, were selected to G publication each week and to Brooke Ashton for perform at the Opera House in Encore next proof reading each edition. year. Congratulations, boys! In the ‘Flickerup’ competition, James Walker (9M) was High Talent nominated for his film ‘Pollution’ as was Victor Barberis Cup victory! Sydney High has not won Zhang (10R) for his animation. Jared Smith this interschool U15s cricket cup for five years. (SHS-2019) was awarded a Macquarie University Leaders and Achievers scholarship H for Marketing and Media, valued at $50,000. Congratulations, Jared! Interpreting Year 10 Reports – Semester 2 All Year 10 boys should now have their reports. Parents are advised to work with their sons in the process of choosing Year 11 courses. Choosing courses for Year 11 study can be assisted by evaluations of Year 10 Melbourne High have had our measure.