Making a Whore of Freedom: Bu¨Chner's Marion Episode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Einem Gottfried

EINEM VON GOTTFRIED Compositore austriaco (Berna 24 I 1918 - Waldviertel 12 VII 1966) Dapprima autodidatta, Gottfried von Einem studiò con Boris Blacher e sviluppò in seguito un equilibrato linguaggio musicale. Nel 1938 iniziò la sua carriera come istruttore di canto all'Opera di Berlino e come assistente al Festival di Bayreuth. Durante il nazionalsocialismo venne più volte arrestato. Dopo la guerra Einem rivestì varie funzioni sia al Festival di Salisburgo, sia alle Festwochen di Vienna. Dal 1963 al 1972 insegnò alla Musikhochschule di Vienna, dal 1964 fu membro della Akademie der Kunste di Berlino e dal 1965 al 1970 presidente dell'Akademie fur Musik austriaca. 1 DANTONS TOD Di Gottfried von Einem (1918-1996) libretto proprio e di Boris Blacher, dal dramma di Georg Büchner (La morte di Danton) Opera in due atti e sei quadri Prima: Salisburgo, Felsenreitschule, 6 agosto 1947 Personaggi: Georges Danton (Bar); Julie, sua moglie (Ms); Camille Desmoulins e Jean Hérault de Séchelles, deputati (T); Lucille, moglie di Camille (S); Maximilien Robespierre (T); Saint-Just (B); Simon, suggeritore (B); due becchini (T); una dama (S); una popolana (A); uomini e donne del popolo In Dantons Tod non si saluta solo un esordio teatrale particolarmente felice, tanto da decretare all’autore fama subitanea, ma anche l’inizio della consuetudine salisburghese (mai più abbandonata) di inserire ogni anno nel Festival un’opera contemporanea in ‘prima’ assoluta. Il soggetto di Büchner venne scelto sull’onda emotiva suscitata dal fallito attentato a Hitler nel 1944; ad approntare la versione ridotta fu Boris Blacher, maestro di Einem e futuro dedicatario dell’opera. -

Avra Xepapadakou

Avra Xepapadakou University of Crete Maria Antonietta: Pavlos Carrer’s last Italian opera and second European attempt1 In the summer of 1873, Pavlos Carrer agrees with his friend, poet Conte Giorgio D. Roma,2 to work together on the libretto of a new opera based on the “episode of the French Revolution concerning Marie Antoinette”.3 The choice of the subject raises questions, since it forms the only exception among the five Greek national operas that Pavlos Carrer composes from 1868 until the end of his life.4 The composer does not state, his sources, therefore we do not know whether he and Roma studied the history of the French Revolution and, consequently, drew the inspiration for their libretto from it or worked on a literary text. Further below, we will examine that both may be the case. The composer describes vividly the carefree, summer days when both of them, living in Zante, worked together for the creation of the opera’s libretto, while talking and laughing until midnight. Roma, as Carrer explains, was so enthusiastic with the new opera that his “pen was running too fast”. Many times the composer was obliged to make cuts at the “extremely and beyond any rule lengthy lyrics”, driving the librettist to express his strong opposition: 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conference The Ionian Opera and Musical Theatre until 1953, University of Athens-Dept. of Theatre Studies, Athens State Orchestra & Athens Concert Hall, 23-24 April 2010 and was published in its Proceedings, pages 134-144. 2 More about Carrer’s librettist in De Viasis, Spyridon. -

©Copyright 2013 Jan Hengge

©Copyright 2013 Jan Hengge Pure Violence on the Stage of Exception: Representations of Revolutions in Georg Büchner, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Heiner Müller, and Elfriede Jelinek Jan Hengge A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Richard Block, Chair Eric Ames Brigitte Prutti Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics University of Washington Abstract Pure Violence on the Stage of Exception: Representations of Revolutions in Georg Büchner, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Heiner Müller, and Elfriede Jelinek Jan Hengge Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Richard Block Department of Germanics This dissertation examines pertinent issues of today’s terrorism debate in frequently overlooked earlier representations of revolutionary and state violence. At the center of this debate is the state of exception through which the sovereign legitimizes the juridical order by suspending preexisting civil laws. As recent theorists have argued, this has become the paradigm for modern nation states. Walter Benjamin contends, however, that a permanent state of exception has existed since the Baroque and has subjected its victims to an empty eschaton, an end without messianic redemption and devoid of all meaning. As long as the order of the sovereign is based on the dialectical relationship between law- making and law-preserving violence, this state will persevere and the messianic promise will not come to fruition. Thus Benjamin conceives of another category of violence he calls “pure violence,” which lies outside of the juridical order altogether. This type of violence also has the ability to reinstate history insofar as the inevitability of the state of exception has ceased any historical continuity. -

Legislative Assembly Approve Laws/Declarations of War Must Pay Considerable Taxes to Hold Office

Nat’l Assembly’s early reforms center on the Church (in accordance with Enlightenment philosophy) › Take over Church lands › Church officials & priests now elected & paid as state officials › WHY??? --- proceeds from sale of Church lands help pay off France’s debts This offends many peasants (ie, devout Catholics) 1789 – 1791 › Many nobles feel unsafe & free France › Louis panders his fate as monarch as National Assembly passes reforms…. begins to fear for his life June 1791 – Louis & family try to escape to Austrian Netherlands › They are caught and returned to France National Assembly does it…. after 2 years! Limited Constitutional Monarchy: › King can’t proclaim laws or block laws of Assembly New Constitution establishes a new government › Known as the Legislative Assembly Approve laws/declarations of war must pay considerable taxes to hold office. Must be male tax payer to vote. Problems persist: food, debt, etc. Old problems still exist: food shortages & gov’t debt Legislative Assembly can’t agree how to fix › Radicals (oppose monarchy & want sweeping changes in gov’t) sit on LEFT › Moderates (want limited changes) sit in MIDDLE › Conservatives (uphold limited monarchy & want few gov’t changes) sit on RIGHT Emigres (nobles who fled France) plot to undo the Revolution & restore Old Regime Some Parisian workers & shopkeepers push for GREATER changes. They are called Sans-Culottes – “Without knee britches” due to their wearing of trousers Monarchs & nobles across Europe fear the revolutionary ideas might spread to their countries Austria & Prussia urge France to restore Louis to power So the Legislative Assembly ………. [April 1792] Legislative Assembly declares war against Prussia and Austria › Initiates the French Revolutionary Wars French Revolutionary Wars: series of wars, from 1792-1802. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

And Voltaire's

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POPE’S “ESSAY ON MAN” AND VOLTAIRE’S “DISCOURS EN VERS SUR L’HONME” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS BY ANNIE BERNICE WIMBUSH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ATLANTA, GEORGIA NAY 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . a a . • • • . iii. Chapter I. THENENANDTHEIRWORKS. a• • • • • . a aa 1 The Life of Alexander Pope The Life of Voltaire II. ABRIEFRESUNEOFTHETWOPOENS . aa • . • •. a a 20 Pope’s “Essay on Man” Voltaire’s “Discours En Vers Sur L’Hoimne” III. A COMPARISON OF THE TWO POEMS . a • • 30 B IBLIOGRAPHY a a a a a a a a a a a • a a a • a a a a a a a 45 ii PREFACE In the annals of posterity few men of letters are lauded with the universal renown and fame as are the two literary giants, Voltaire and Pope. Such creative impetus and “esprit” that was uniquely theirs in sures their place among the truly great. The histories and literatures of France and England show these twQ men as strongly influential on philosophical thinking. Their very characters and temperaments even helped to shape and transform man’s outlook on life in the eighteenth century and onward.. On the one hand, there is Voltaire, the French poet, philosopher, historian and publicist whose ideas became the ideas of hundreds of others and whose art remains with us today as monuments of a great mind. On the other there is Pope, the English satirical poet and philosopher, endowed with a hypersensitive soul, who concerned himself with the ordinary aspects of literary and social life, and these aspects he portrayed in his unique and excellent verse, Both men were deeply involved in the controversial issues of the time. -

Classical Images As Allegory During the French Revolution

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Visioning The Nation: Classical Images As Allegory During The French Revolution Kristopher Guy Reed University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Reed, Kristopher Guy, "Visioning The Nation: Classical Images As Allegory During The French Revolution" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3312. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3312 VISIONING THE NATION: CLASSICAL IMAGES AS ALLEGORY DURING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION by KRISTOPHER G. REED BA Stetson University, 1998 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2007 Major Professor: Amelia Lyons ABSTRACT In the latter half of the Eighteenth Century, France experienced a seismic shift in the nature of political culture. The king gave way to the nation at the center of political life as the location of sovereignty transferred to the people. While the French Revolution changed the structure of France’s government, it also changed the allegorical representations of the nation. At the Revolution’s onset, the monarchy embodied both the state and nation as equated ideas. -

The Subversive Court of Louise Bénédicte De Bourbon, Daughter-In-Law of the Sun King (1700–1718)”

Phi Alpha Theta Pacific Northwest Conference, 8–10 April 2021 Jordan D. Hallmark, Portland State University, graduate student, “Parody, Performance, and Conspiracy in Early Eighteenth-Century France: The Subversive Court of Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon, Daughter-in-Law of the Sun King (1700–1718)” Abstract: This paper examines how the French princess Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon, duchesse du Maine (1676–1753), the wife of Louis XIV’s illegitimate son, the duc du Maine, established an exclusive court at her château de Sceaux beginning in the year 1700 that challenged the centralized cultural system of the French monarchical state. Located twenty kilometers away from the rigid and controlling political center of Versailles, the court of the duchesse du Maine subverted social norms by inventing and performing parodies of court protocols, chivalric orders, emblems, and other forms of monarchical imagery. In a time and place where women were both legally and socially barred from holding positions of authority, the duchesse du Maine created a parallel world in which she was the sovereign, presiding over a court of important political, cultural, and intellectual figures, including the philosopher Voltaire. By considering the significance of this subversive court culture in the context of the factional divisions and dynastic crises emerging in the last years of Louis XIV’s reign, this paper will show how the seemingly frivolous aristocratic divertissements of the duchesse du Maine and her circle were informed by political, social, and dynastic ambitions that would culminate in a conspiracy to overthrow the French regent, Philippe d’Orléans, in 1718. “Parody, Performance, and Conspiracy in Early Eighteenth-Century France: The Subversive Court of Louise-Bénédicte de Bourbon, Daughter-In-Law of the Sun King (1700–1718)” by Jordan D. -

The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason Timothy Scott Johnson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1424 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE FRENCH REVOLUTION IN THE FRENCH-ALGERIAN WAR (1954-1962): HISTORICAL ANALOGY AND THE LIMITS OF FRENCH HISTORICAL REASON By Timothy Scott Johnson A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 TIMOTHY SCOTT JOHNSON All Rights Reserved ii The French Revolution in the French-Algerian War (1954-1962): Historical Analogy and the Limits of French Historical Reason by Timothy Scott Johnson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Richard Wolin, Distinguished Professor of History, The Graduate Center, CUNY _______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _______________________ -

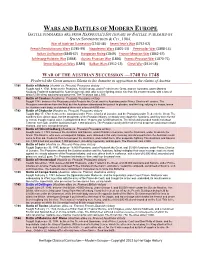

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Timeline (PDF)

Timeline of the French Revolution 1789 1793 May 5 Estates General convened in Versailles Jan. 21 Execution of Louis XVI (and later, Marie Jun. 17 National Assembly Antoinette on Oct. 16) Jun. 20 Tennis Court Oath Feb. 1 France declares war on British and Dutch (and Jul. 11 Necker dismissed on Spain on Mar. 7) Jul. 13 Bourgeois militias in Paris Mar. 11 Counterrevolution starts in Vendée Jul. 14 Storming of the Bastille in Paris (official start of Apr. 6 Committee of Public Safety formed the French Revolution) Jun. 1-2 Mountain purges Girondins Jul. 16 Necker recalled Jul. 13 Marat assassinated Jul. 20 Great Fear begins in the countryside Jul. 27 Maximilien Robespierre joins CPS Aug. 4 Abolition of feudalism Aug. 10 Festival of Unity and Indivisibility Aug. 26 Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen Sept. 5 Terror the order of the day Oct. 5 Adoption of Revolutionary calendar 1791 1794 Jun. 20-21 Flight to Varennes Aug. 27 Declaration of Pillnitz Jun. 8 Festival of the Supreme Being Jul. 27 9 Thermidor: fall of Robespierre 1792 1795 Apr. 20 France declares war on Austria (and provokes Prussian declaration on Jun. 13) Apr. 5/Jul. 22 Treaties of Basel (Prussia and Spain resp.) Sept. 2-6 September massacres in Paris Oct. 5 Vendémiare uprising: “whiff of grapeshot” Sept. 20 Battle of Valmy Oct. 26 Directory established Sept. 21 Convention formally abolishes monarchy Sept. 22 Beginning of Year I (First Republic) 1797 Oct. 17 Treaty of Campoformio Nov. 21 Berlin Decree 1798 1807 Jul. 21 Battle of the Pyramids Aug. -

Score Catalogue 2013

Universal Edition Scores www.universaledition.com wien | london | new york UNIVERSAL EDITION SCORES Composer / Arranger Title Instrumentation Kind of Edition Language UE_No Euro Code NEW STUDY SCORES SERIES Bartók Béla Cantata profana The Magic Deer for tenor, bartione, choir SATB and orchestra New Study Scores Series German; English UE34300 31,95 nn Bartók Béla Dance Suite for orchestra New Study Scores Series UE34308 19,95 nn Music for Stringed Instruments, Percussion and Bartók Béla for strings, percussion and celeste New Study Scores Series UE34129 23,95 nn Celeste Bartók Béla Piano Conerto No. 1 for piano and orchestra New Study Scores Series UE34307 52,95 nn Bartók Béla String Quartet No. 2 op. 17 for string quartet New Study Scores Series UE34309 18,95 nn Bartók Béla String Quartet No. 3 for string quartet New Study Scores Series UE34310 17,95 nn Bartók Béla String Quartet No. 4 for string quartet New Study Scores Series UE34311 19,95 nn Bartók Béla String Quartet No. 5 for string quartet New Study Scores Series UE34312 22,95 nn The Miraculous Mandarin A Ballet in 1 Act. Libretto Bartók Béla for orchestra New Study Scores Series UE34110 46,95 nn by Menyhért Lengyel 5 Orchestral Songs After postcard texts by Peter Berg Alban for medium voice and orchestra New Study Scores Series UE34123 15,95 nn Altenberg Berg Alban 7 frühe Lieder for high voice and orchestra New Study Scores Series German UE35547 24,95 nn Berg Alban Chamber Concerto for piano and violin with 13 wind instruments New Study Scores Series UE34116 32,95 nn Berg Alban Der Wein Konzertarie mit Orchester for soprano and orchestra New Study Scores Series German; French UE34125 27,95 nn Berg Alban Lulu Suite Symphonic Pieces from the Opera "Lulu" for orchestra and colotura soprano New Study Scores Series German UE34115 41,95 nn Lyric Suite Neuausgabe 2005 George Perle (inkl.