Programme in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somalia Nutrition Cluster

SOMALIA NUTRITION CLUSTER Banadir Sub-national Nutrition Cluster Meeting Monday 18th July 2016, 10.00 AM, ANNPCAN Meeting Hall, Near Samira Hotel KM5, Hodan district, Mogadishu-Somalia 1. Introduction and registration of participants Hashim Aden, nutrition cluster focal point chaired the meeting and welcomed Dr Mohamed Alasow of MoH-Banadir Regional Nutrition Coordinator for opening remarks. The meeting opened with Holy Quran followed by round table introductions. Hashim introduced the meeting agenda and call out additional agenda. No any other additional agenda put forth. 2. Review of Previous Meetings and Action Points The previous meeting minutes and action points has been reviewed and approved as a correct record in page 3 & 4. 3. Key Nutrition services and situation highlights SOS; confirmed to have stopped new admission in June since the contract ended by their funding agency (CRS). However, they are referring OTP cases to RI in Waxare Cade in Heliwa district. They have enough stock for TSFP programs and their Field Level Agreement (FLA) will expire on Dec-2016. Consequently, they facing supply shortage for the SC program. ACF; started a kitchen garden for the communities in Abdiaziz district and the first cash crop harvested was spinach. Besides, they confirmed to have a shortage of F-75 and F-100 for the SC program. On 9th July, 9 SAM with medical complication cases admitted in their Forlinin SC from Karaan district and Middle Shabelle region. They therefore requested an update from the mentioned area. Mercy USA; started two health and nutrition facilities on May in Yaqshid district. They have enough supplies and their FLA will expire on Dec-2016. -

CHF 1St Allocation Tri-Cluster.Pdf

WASH Coord & Plan Shelter Health CHF First Allocation Tri Cluster Strategy – IDP settlement response, Mogadishu 1. Introduction At the CHF board meeting on 17th February 2012, $10.75 million was allocated for a tri-cluster response to address IDPs. More specifically the objectives of the funding were: i. improve living conditions of secondary displaced populations in Mogadishu, ii. respond to needs of newly displaced in Mogadishu and other priority areas, iii. mainstream protection and encourage protection based programming in all programmes focusing on IDPs. The Shelter/NFI, Health and WASH Clusters wrote a broad strategy which set-out how these objectives would be achieved and how the funding was divided between the Clusters. The CHF board accepted the strategy and so this follow-up paper attempts to operationalise the Tri-Cluster Strategy.1 On the 7th May 2012, representatives of the three Clusters met with Tri-Cluster partners and stakeholders to discuss the strategy and how it would practically work on the ground.2 There were a number of issues raised which this paper will address. The launch of the strategy on 20th June 2012 raised another set of concerns and issues. These have been addressed and consolidated in the 10 working principles of the tri-cluster, attached at the end of this document. 2. Coordination and Management The day-to-day management of the projects will be by the partners and reporting lines through the CHF will be maintained. However, as there are 14 partners and 16 projects and considering the challenging nature of Mogadishu to enhance the impact, a Tri-Cluster Coordinator (TCC) and Tri-Cluster Settlement Planner (TCSP) have been recruited3. -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

Agulhas and Somali Currents Large Marine Ecosystems Project

Agulhas and Somali Currents Large Marine Ecosystems Project Capacity Building and Training Component National Training Plan for SOMALIA Prepared by: Mr. Hassan Mohamud Nur 1) Summary of key training requirements a) Skill training for fishers. b) To strength the scientific and management expertise c) To introduce an ecosystem approach to managing the living marine resources d) To enhance the local and international markets. e) To secure processing systems f) To upgrade environmental awareness and waste management and marine pollution control g) To create linkages between the local community and the international agencies 2) introduction: Somalia has 3,333Km of coast line of which 2,000Km is in the Indian Ocean south of Cape Guardafui and 1,333Km of north shore of Gulf of Aden. Surveys indicate high potential for fisheries development with evenly distributed fish stocks along the entire coastline, but with greater concentration in the Northeast. The fishing seasons are governed by two monsoon winds, the south west monsoon during June to September and northeast monsoon during December to March and two inter-monsoon periods during April/May and October/November. In the case of Somalia, for the last two decades the number of people engaged in fisheries has increased from both the public and private sector. Although, the marine fisheries potential is one of the main natural resources available to the Somali people, there is a great need to revive the fisheries sector and rebuild the public and private sector in order to promote the livelihood of the Somali fishermen and their families. 3) Inventory of current educational Capacity Somalia has an increasing number of elementary and intermediate schools, beside a number of secondary and a handful of universities. -

Somalia and Eritrea Addressed to the President of the Security Council

United Nations S/2013/413 Security Council Distr.: General 12 July 2013 Original: English Letter dated 12 July 2013 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea, and in accordance with paragraph 13 (m) of Security Council resolution 2060 (2012), I have the honour to transmit herewith the report on Somalia of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. In this connection, the Committee would appreciate it if the present letter, together with its enclosure, were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Kim Sook Chairman Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea 13-36185 (E) 150713 *1336185* S/2013/413 Letter dated 19 June 2013 from the members of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea We have the honour to transmit herewith the report on Somalia of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, in accordance with paragraph 13 (m) of Security Council resolution 2060 (2012). (Signed) Jarat Chopra Coordinator Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea (Signed) Jeanine Lee Brudenell Finance Expert (Signed) Emmanuel Deisser Arms Expert (Signed) Aurélien Llorca Transport Expert (Signed) Dinesh Mahtani Finance Expert (Signed) Jörg Roofthooft Maritime Expert (Signed) Babatunde Taiwo Armed Groups Expert (Signed) Kristèle Younès Humanitarian Expert 2 13-36185 S/2013/413 Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security Council resolution 2060 (2012): Somalia Contents Page Abbreviations................................................................. -

Federal Republic of Somalia

Federal Republic of Somalia Education Statistics Yearbook 2013/2014 Ministry of Education and Higher Education Department of Policy and Planning EMIS unit April 2015 Mogadishu, Somalia Website: www.moesomalia.net Department of Policy and Planning Education Management Information System unit Mogadishu, Somalia Tel: +252 90-7707872 Website: www.moesomalia.net Email: [email protected] © Ministry of Education and Higher Education This publication may be used in part or as a whole, provided that the EMIS is acknowledged as the source of the information. Whilst the EMIS does all it can to accurately consolidate and integrate Somalia education information, it cannot be held liable for incorrect data and for errors in conclusions, opinions and interpretations emanating from the information. Furthermore, the EMIS cannot be held misinterpretation of the statistical content of the publication. This publication has been produced with financial support from the government of the Netherlands through the Peace Building, Education and Advocacy (PBEA) programme and technical assistance from UNICEF. A complete set of the yearbook will be available at the following addresses: • EMIS Unit, MOEHE, Mogadishu, Somalia • MOEHE’s website: www.moesomalia.net For more inquiries or requests, please use the following contact information: Said Yusuf Mohammed, EMIS Focal Person, MOEHE Somalia, [email protected] i Foreword ii Tables of Contents ACRONYMS .......................................................................................................................................... -

Somalia Snapshot 130225 5

Somalia: Humanitarian Snapshot, February 2013 | Issued on 6 March 2013 The March to May Gu rains are expected to be Fire outbreak at an Internally displaced people (IDPs) YEMEN ‘normal’ to ‘below normal’ according to the latest IDP camp DJIBOUTI 215,300 relocation in Mogadishu data from the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis 17,000 Refugees The Federal Government of Somalia plans to Refugees Unit (FSNAU) and the Famine Early Warning Systems Bossaso relocate IDPs in Mogadishu to government Network (FEWSNET). With the rains expected to be owned land on the outskirts of the city. average to below average, the food insecure Ceerigaabo AWDAL Humanitarian partners are working with the population will likely increase although slightly. The SANAAG government to help them ensure that the Borama W. GALBEED BARI primary areas most likely to be affected are the maize relocations are conducted in a humane and Burco 84,000 growing agro- pastoral areas of the South. Hargeysa IDPs in Somaliland ethical manner in accordance with established standards. SOOL Access and Insecurity Food security Malnutrition TOGDHEER Laas Caanood Garowe Rural, urban and IDP population NUGAAL Insecurity remained a key challenge throughout 215,000 acutely malnourished children the country in February. An explosion occurred 1.67 million in stress 129,400 in Mogadishu's Abdiaziz District. The IDPs in Puntland ETHIOPIA vehicle-borne improvised explosive device 1.05 million in crisis and emergency (including IDPS) Gaalkacyo (VBIED) attack was carried out by a suicide 209,000 bomber. One person was confirmed dead and Percentage of population in crisis and emergency Refugees three others were injured. -

Somali Urban Resilience Project

Public Disclosure Authorized SOMALI URBAN RESILIENCE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized P163857 Resettlement Action Plan Public Disclosure Authorized Mogadishu Contract B: 19 Community Roads rd Public Disclosure Authorized Date: 3 January 2019 Authors: Dr. Yahya Y. Omar & Mrs. Desta Solomon PROJECT DETAILS Project Name Somali Urban Resilience Project Grant Number TF-A8112 Project Number P163857 Grant Recipient Federal Government of Somalia Project Implementing Benadir Regional Administration/Municipality of Entity Mogadishu Project TTL Zishan Karim Project Co-TTL Makiko Watanabe Social Safeguards Desta Solomon Specialist Project Coordinator Omar Hussein Project Focal Point Mohamed Hassan Data Assistant Nabil Abdulkadir Awale ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................ v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................... v DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... ix 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 12 1.1 Project Background ................................................................................................ 12 1.2 Project Context ...................................................................................................... -

SOMALIA National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP)

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF SOMALIA National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) December, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document should be cited as follows: Ullah, Saleem and Gadain, Hussein 2016. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) of Somalia, FAO-Somalia. Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 12 1.1. Background to the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: ............................. 12 1.2. Overview of the NBSAP development process in Somalia ........................................... 12 1.3. Structure of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan .................................. 16 1.4. Understanding biodiversity ............................................................................................ 17 1.5. Importance of biodiversity ............................................................................................. 17 1.6. Generic Profile of Somalia ............................................................................................ -

The UN in Somalia

The UN in Somalia The UN in Somalia 2014 The UN in Somalia 2 The UN in Somalia A little more about Somalia Early in the thirteenth century, Somalia had already been recognised as an ideal stopover for British ships travelling to India and other places. Italy and France had also set up coaling stations for their ships in the northern parts of the country. Later in the century, the British, Italians and French began to compete over Somali territory. Around then, neighbouring Ethiopia also took interest in taking over parts of Somalia. A string of treaties with Somali clan leaders resulted in the establishment of the British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland. Around this time, Egypt tried to claim rights in selected areas of the country. Following a long struggle, in 1920, British and Italian protectorates occupied Somalia. In 1941, a British military administration took over the country. As a result, north-western Somalia remained a protectorate, while north-eastern and south and central Somalia became a UN Trusteeship in April 1950, with a promise of independence after ten years. A British protectorate, British Somaliland in the north-west became independent on 26 June 1960. Less than a week later, the Italian protectorate gained independence on 1 July 1960. The two states merged to form the Somali Republic under a civilian government. However, Somalia was far from stable. In 1969, a coup d’etat took place and President Abdi Rashid Ali Shermarke was assassinated. Mohammed Siad Barre, who led this overthrowing of the government, took charge as the President of Somalia, and tried to reclaim Somali territory from Ethiopia during his tenure. -

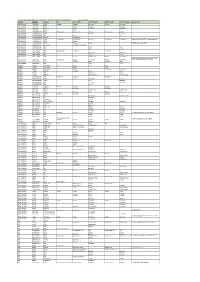

Region District Partner SC OTP Static OTP Mobile TSFP Static TSFP

NUTRITION CLUSTER SOUTH CENTRAL ZONE RATIONALIZATION PLAN 15 April, 2014 Region District Partner SC OTP Static OTP Mobile TSFP Static TSFP Mobile Comments GALGADUUD CADAADO HRDO Cadaado Cadaado Biyogadud Cadaado Biyogadud GALGADUUD CADAADO HRDO Baxado Docole Docoley GALGADUUD CADAADO Observer Galinsor Gondinlabe Gondinlabe GALGADUUD CADAADO Observer Adado Baxado GALGADUUD DHUSAMAREEB TUOS Dhusamareeb Dhusamareeb Gadoon Dhusamareeb Gadoon GALGADUUD DHUSAMAREEB TUOS El -Dheere El -Dheere GALGADUUD DHUSAMAREEB WCI Guri-el Guri-el GALGADUUD DHUSAMAREEB Observer Dhusamareeb GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ HDOS Caabudwaaq Caabudwaaq Bangeele Caabudwaaq Caabudwaaq I static and 1 mobile TSFP in Cabduwaaq town GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ HDOS Baltaag GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ HOPEL Balanbale Balanbale Balanbale will be semi-static GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ Mercy USA Cabudwaaq Town West GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ HDO Xerale Xerale GALGADUUD CAABUDWAAQ SCI Dhabat Dhabat GALGADUUD CEEL DHEER CISP CEEL DHEER Ceel Dheer Ceel Dheer GALGADUUD CEEL DHEER SRC Hul Caduur Hul Caduur GALGADUUD CEEL DHEER SRC Oswein Oswein GALGADUUD CEEL DHEER Merlin Galcad Mesagaweyn Galcad Mesagaweyn DEH to inform on discussion with Merlin or else GALGADUUD CEEL BUUR Merlin CEEL BUUR Elgaras Ceel Qooxle Elgaras Ceel Qooxle Merlin will manage Ceel buur SC&OTP GALGADUUD CEEL BUUR Merlin Ceel Buur Jacar Ceel Buur Jacar GALGADUUD CEEL BUUR DEH Xindhere Xindhere MUDUG HOBYO Mercy USA Wisil Hobyo Wisil Hobyo MUDUG HOBYO Mercy USA El dibir El dibir MUDUG HOBYO Mercy USA Gawan Ceelguula Ceelguula MUDUG HOBYO GMPHCC -

Marqaati 2016 Corruption Report

Somalia State of Accountability 2016 marqaati February 7 2016 State of Accountability in Somalia 2017 In 2016, all brakes were removed and corruption hit an all-time high. Payment of salaries was stopped and government property Unrestrained sold off in order to fund the most expensive vote-buying campaign in human history. 2017 will see an uptick in mid and low-level corruption, especially in food aid. Corruption Somalia State of Accountability 2016 marqaati Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Somalia’s federal elections: August 2016 – February 2017 .......................................................................... 4 Intimidation and harassment .................................................................................................................... 4 Bribery ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Elders ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Delegates