Three Novel Readings of Paul Kor's the Elephant Who Wanted to Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AJL CONVENTION OAKLAND, CA Tried and True Favorites from Janice R

CHILDREN’S HEBREW BOOKS, VIDEOS/DVDs, AND WEBSITES: WHERE DO I FIND THEM, AND WHAT’S NEW OUT THERE? Presented by Janice Resnick Levine, Judaics Media Specialist at The Epstein Solomon Schechter School of Atlanta Description: There is a large world of Hebrew children’s books, videos, and websites available now. Since Hebrew books and videos for children are produced mainly for Israelis how do we find suitable ones for our day school, synagogue, or resource libraries here in the U.S.? This presentation will focus on how to choose Hebrew children’s materials, where to purchase them, a refresher on cataloging those materials, and a glimpse at some of the newer Hebrew children’s books and videos one can purchase for your library. It will also highlight some of the Hebrew children’s websites available for learning to read and speak Hebrew. Janice Resnick Levine has been Judaics Media Specialist at the Epstein Solomon Schechter This is an update of a session that I gave at the School of Atlanta since 1994. Prior to that she was AJL Convention in San Diego in June, 2001. part-time librarian for the Temple Beth El Hebrew Consequently, there will be some of the same School Library in Syracuse, NY. She has also worked as an information specialist for Laubach information in this paper. Literacy International and Central City Business Institute in Syracuse, NY. She received a BS in There is a large selection of Hebrew Education from the Pennsylvania State University and a Masters in Library Science from Syracuse children’s books and videos from Israel University. -

The Story of Israel As Told by Banknotes

M NEY talks The Story of Israel as told by Banknotes Educational Resource FOR ISRAEL EDUCATION Developed, compiled and written by: Vavi Toran Edited by: Rachel Dorsey Money Talks was created by Jewish LearningWorks in partnership with The iCenter for Israel Education This educational resource draws from many sources that were compiled and edited for the sole use of educators, for educational purposes only. FOR ISRAEL EDUCATION Introduction National Identity in Your Wallet “There is always a story in any national banknote. Printed on a white sheet of paper, there is a tale expressed by images and text, that makes the difference between white paper and paper money.” Sebastián Guerrini, 2011 We handle money nearly every day. But how much do we really know about our banknotes? Which president is on the $50 bill? Which banknote showcases the White House? Which one includes the Statue of Liberty torch? Why were the symbols chosen? What stories do they tell? Banknotes can be examined and deciphered to understand Like other commemoration the history and politics of any nation. Having changed eight agents, such as street times between its establishment and 2017, Israel’s banknotes names or coins, banknotes offer an especially interesting opportunity to explore the have symbolic and political history of the Jewish state. significance. The messages 2017 marks the eighth time that the State of Israel changed the design of its means of payment. Israel is considered expressed on the notes are innovative in this regard, as opposed to other countries in inserted on a daily basis, in the world that maintain uniform design over many years. -

Der Dornbusch, Der Nicht Verbrannte Überlebende Der Shoah in Israel

Der Dornbusch, der nicht verbrannte Überlebende der Shoah in Israel Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Der Dornbusch, der nicht verbrannte Überlebende der Shoah in Israel Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Übersetzung aus dem Hebräischen Rachel Grünberger-Elbaz Im Auftrag der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel und des Beit Berl Academic College Für die Inhalte der Beiträge tragen allein die Autorinnen und Autoren die Verantwortung. Diese stellen keine Meinungsäußerung der Herausgeber, der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung und des Beit Berl Academic College, dar. Herausgeberin: Miri Freilich Deutsche Ausgabe: Anita Haviv und Ralf Hexel Lektorat: Astrid Roth Umschlag und graphische Gestaltung: Esther Pila Satz: A.R. Print Ltd. Israel Deutsche Ausgabe 2012: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel P.O.Box 12235 Herzliya 46733 Israel Tel. +972 9 951 47 60 Fax +972 9 951 47 64 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Berlin Hiroshimastraße 17 D - 10785 Berlin Tel. +49 (0)30 26 935 7420 Fax +49 (0)30 26 935 9233 ISBN 978-3-86498-300-9 Hebräische Ausgabe: © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Israel 2011 Printed in Israel Inhalt Ralf Hexel Vorwort zur deutschen Ausgabe 6 Tamar Ariav Vorwort 9 Wladimir Struminski Der Optimist – Erinnerung an Noach Flug 11 Anita Haviv In memoriam Moshe Sanbar 14 Eliezer Ben-Rafael Die Shoah in der kollektiven Identität und politischen Kultur Israels 16 Hanna Yablonka Shoah-Überlebende in Israel – Schlüsselereignisse und wichtige Integrationsphasen 32 Eyal Zandberg Zwischen Privatem -

LC's Israel and Judaica

LC’s Israel and Judaica (IJ) Section Update AJL Conference, Woodland Hills, California Tuesday, June 18, 2019 Haim Gottschalk ([email protected]) Roger Kohn ([email protected]) Yisrael Meyerowitz ([email protected]) Gail Shirazi ([email protected]) Jeremiah Aaron Taub ([email protected]) Galina Teverovsky ([email protected] Association of Jewish Libraries Proceedings June 2019 Welcome to the Israel and Judaica Section Update. My name is Aaron Taub, and I am joined by my colleagues Haim Gottschalk, Gail Shirazi, and Galina Teverovsky. Roger Kohn and Yisrael Meyerowitz could not attend the conference and contributed numerous slides and a video segment to this presentation. 1 Israel and Judaica Section Update Agenda • LC General News • In Memoriam • Cataloging Matters • Staff Matters • New Policy on Terminal Periods • Strategic Plan • Other LC Developments • IJ Acquisitions Highlights • PrePub Book Link • Rare Hebrew Children’s Materials • Paul Kor Donation • Policy and Standards Division (PSD) Decisions • Yiddish Posters • Multiples in LCSH • And So Much More! • Jewish hymns • Holocaust deniers • Appendix • • New Subject Headings (e.g. Cataloging Matters Jedwabne) • Hebrew Maps • Jewish-Arab relations (Full • Jewish-Arab Relations (Abstract) Version) • BIBFRAME Update • Determining the Conventional • NAR Queries Name of an Event • Jewish and Israeli Law SubjectAssociation Cataloging of Jewish Libraries Proceedings June 2019 As always, we have a full agenda so we ask that you save your questions and comments until the end. We’ll begin with some general news, and then move into PSD decisions, then cataloging issues and projects, and we’ll end with IJ acquisitions highlights. In the interest of time, the topics in the appendix will not be read today during our presentation but will be included in the proceedings. -

Jo and Pepper and the Big Sleep Hilit Blum

Bologna Catalogue 2017 Kinneret, Zmora-Bitan, Dvir 2 Paul Kor Paul Kor 3 NEW Kaspion Series Best A Hawk or a Dove? Seller Paul Kor Paul Kor English translation available. English translation available. Find out about Kaspion the little silver fish and The day will come when the hawk will turn into a dove, tanks into join him in his numerous adventures - Kaspion tractors and warplanes into butterflies. But meanwhile we can the Little Fish, Kaspion Beware and Kaspion’s 270 x 210 / 30 pages just turn the pages of Paul Kor’s clever book for young Great Journey. readers, and read a story in which war simply turns into Rights sold peace. A touching tale about the eternal hope for peace With colourful and rich illustrations Paul Kor France, English (NA), Germany, Korea, Spanish, by an award-winning author and illustrator. created a world perfect for children to dive into. Catalan & China Kaspion has become his most famous character and has won the Ben-Yitzhak illustration prize from the Israel Museum. The Elephant that Wanted to Be the Most ... Paul Kor Best Seller Also English translation available. Also in bath in board & board All the grey elephants were happy and content book book apart from one young elephant who said: "Grey is an ugly colour!" He looked at his reflexion and cried. So what do you think happened when a bird Also by Paul Kor: covered the young grey elephant with an array of dazzling colours? Paul Kor is one of the most popular children’s book artists in Israel. -

INTERACTIONS Explorations of Good Practice in Educational Work with Video Testimonies of Victims of National Socialism

Education with Testimonies INTERACTIONS Explorations of Good Practice in Educational Work with Video Testimonies of Victims of National Socialism edited by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Education with Testimonies, Vol.4 INTERACTIONS Explorations of Good Practice in Educational Work with Video Testimonies of Victims of National Socialism edited by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Published by Werner Dreier | Angelika Laumer | Moritz Wein Editor in charge: Angelika Laumer Language editing: Jay Sivell Translation: Christopher Marsh (German to English), Will Firth (Russian to English), Jessica Ring (German to English) Design and layout: ruf.gestalten (Hedwig Ruf) Photo credits, cover: Videotaping testimonies in Jerusalem in 2009. Eyewitnesses: Felix Burian and Netty Burian, Ammnon Berthold Klein, Jehudith Hübner. The testimonies are available here: www.neue-heimat-israel.at, _erinnern.at_, Bregenz Photos: Albert Lichtblau ISBN: 978-3-9818556-2-3 (online version) ISBN: 978-3-9818556-1-6 (printed version) © Stiftung „Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” (EVZ), Berlin 2018 All rights reserved. The work and its parts are protected by copyright. Any use in other than legally authorized cases requires the written approval of the EVZ Foundation. The authors retain the copyright of their texts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 11 Günter Saathoff Preface 17 Werner Dreier, Angelika Laumer, Moritz Wein Introduction CHAPTER 1 – DEVELOPING TESTIMONY COLLECTIONS 41 Stephen Naron Archives, Ethics and Influence: How the Fortunoff Video Archive‘s -

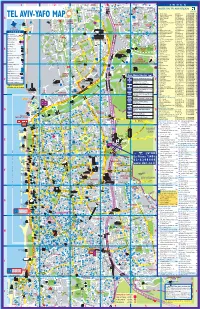

Tel Aviv Nonstop City Busmap

R A SHAIKE OFIR FIA M O HAME’IRI L TI S H TO T E A HAIFA ILLA IS 1 2345H QEH INDEX M AFEQA A AN BUKSPAN H HAMITNADE SH P V T AK LO I NS K I R Y ˘ ÂÏ N R È˜Ò MAGSHIMIM AHAZOR QEHILLA T H HOTELS IN TEL AVIV REGION T ˙ÓÈȘ†Ô¯˜†ß„˘ T PADOVA ILLA E G H A FIR NE’OT V QE VA The Tel Aviv EREN KAYE L O K M E ET AV O U AD S E. I P M B Hotel Association MOT I A A GUR K H S R AFEQA QEHILLAT R A ARSH A MARGALIT T H U H A T V E N ZITOMIR O I F K S IG UT E H OMRI A EMIY M Y KEREN L 1. Abratel Suites 3, Geula St. Tel: 03-5169966 .....G/1 RAVINA QOM Q A A IR A’ L S IG L T S I O N A E KAYEMET D K I ILL L SHAI T R H Z E M S A QEHILLAT KOVNA QE A 2. Alexander All Suits Hotel 3, Havakook St. Tel: 03-5452222 .....E/1 G S H N A H E F T A E INTCHG. I L ASHI SHAIE RISIN E A AV Z H O R R R Berlin ARA M F M I T T E F L E R 3. Arbel Suites Hotel 11, Hulda St. Tel: 03-5225450 .....E/2 A S Q I I N O E Y Y S F Garden E A O IL O R I H U J A K H IG H A Y A OHEN S T I QEHILLAT A 4. -

Eran Neuman / the Israel Pavilion for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal

104 Eran Neuman / The Israel Pavilion for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal Eran Neuman The Israel Pavilion for the 1967 International and Universal Exposition in Montreal Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 26, 2018 105 The launch of the Israel Pavilion at Expo ‘67 in Montreal coincided with a period of enormous political tension in the Middle East, when Israel faced direct threat from surrounding Arab countries, especially its immediate neighbours Egypt, Syria and Jordan. After months of great anxiety, both within the country and in Jewish dias- pora communities abroad, Israel launched a surprise attack and the ensuing Six Day War resulted in a decisive victory for Israel and a major expansion of its territory. Against this backdrop, the Israel Pavilion at Montreal’s global exposition became the focus of international attention even as it did not directly address events happening in the country. Designed over the course of three years by leading Israeli architects Arieh Sharon, David Resnick and Eldar Sharon, as well as several artists and design- ers including Jean David, Shmuel Grundman, Igael Tumarkin, Shraga Weil, Naftali Bezem and Dan Reisinger, the pavilion was at the cutting-edge of contemporary architectural design. Its display concentrated on the history of the Jewish people and building a country in the Promised Land, despite the obstacles. Yet while the pavilion’s design did not deal with the tension between Israel and sur- rounding Arab countries, it did influence Israel’s approach to presenting itself on the global stage. The pavilion’s architecture and display were carefully thought through by government officials, architects, designers and artists who wished to portray the young nation at its best. -

Veterans Getting Discharge

■ r Complete Local News Of A Populatip/ Of- THE WEATHER I Cloudy, scattered showers to 18,556---- day, cloudy, warmer tomorrow. A ■ ■ h ■ - Enter,■(! na second oIbsm mall matUr, January 31, 1925. at the PoBt Office at Elizabeth. Mew Jersey, under the Act of MA'r^Hv-a. 1879, Vol. XXI, No. 1084 ESTABLISHED 1924 HILLSIDE, N. J., THURSDAY, AUGUST 2, 1945 OFFICIAL NFAVNPAPKIt OF TIIE TOWNSHIP OF HILLSIDE PRICE FIVE CENTS Beno Now Stationed “Morrie” Walker Gambling In Central Pacific Stops Veterans Eligible Fathers Invited To Wearing the Purple Heart, the In Field Service Ameiican Defense Ribbon, the Asi lit Subscription War Dads Meeting Monday Fred Morris Walker, 19 years old, More Veterans atic Pacific Ribbon with two Battle son of Mr. and Mrs. Fred Walker, ■^lyr*—^■«*++d—tb#- — infantry— Combat of 1484 North Broad street, left Fnds,Show Badge, P.F.C. Martin L. Beno, S e t t ir c Arthur Muller W ill early last month for. the South Racket Hllclflc nren with— thr— American whose wife, Mrs. Isabel E. Beno, Take Applications a son or daughter serving or who and mother, Mrs. Susan Beno, re Woman Suspicious has served in the armed forces .or Field Service. He is attached to the side at 22H Silver in rom in The ‘Hillside Chapter of ’the who has been designated to act in medical division, and will engage Getting Discharge side at 228 Silver avenue, Hillside Continues N. J„ is now stationed at a base Of Working Way American War Dads w ill meet next the capacity of a War Dad by in ambulance driving and advanced in the Central Pacific. -

The Canadian Jewish Connection to the Visual Narrative of Nationhood

Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 26, 2018 135 Loren Lerner The Canadian Jewish Connection to the Visual Narrative of Nationhood at the Jewish Palestine Pavilion in New York (1939) and the Pavilions of Israel and Judaism in Montreal (1967) Loren Lerner / The Canadian Jewish Connection to the Visual Narrative of Nationhood at the Jewish 136 Palestine Pavilion in New York (1939) and the Israel Pavilion and Pavilion of Judaism in Montreal (1967) Erwin Panofsky was a renowned German-Jewish art historian who settled in the United States in 1934 after the Nazis came to power. He wrote Studies in Iconology (1939) and Meaning in the Visual Arts (1955), two canonical texts that are still at the core of art historical studies today.1 In these writings he explains that art-related images are associated with concepts that originate in Weltanschauung, namely the way of thinking that determines our perceptions of, and interactions with, the world. Along these lines, the primary objective of this article is to consider the evolution of images relating to Israel’s visual narrative of nationhood as found in the pavilions at two World’s Fairs: New York City in 1939 and Montreal in 1967. The secondary objective is to demonstrate how this evolution interacted with Canadian Jewish attitudes and beliefs about Israel. The development of this visual narrative of nationhood began with the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts, founded in Jerusalem by the artist Boris Schatz.2 Schatz wanted to create an expression of national and spiritual independence that synthe- sized European artistic traditions with the local culture of the Land of Israel. -

ערב לזכרו של ריהור )ג'ורג'( אוסטרובסקי December 2010 דצמבר

Jerusalem Film Center ערב לזכרו של ריהור )ג’ורג’( אוסטרובסקי Evening In Memory of Rehor (George) Ostrovsky פסטיבל הקולנוע היהודי Jewish Film Festival December 2010 מחווה למייק לי Mike Leigh Tribute דצמבר שבוע קולנוע קרואטי Croatian Film Week החודש בסינמטק This Month at the Cinematheque החודש בסינמטק This Month at the Cinematheque פסטיבל הקולנוע בין איכרים – הקרנה היהודי מיוחדת Among Peasants - 12th Jewish Film Special Screening Festival 15.12.10 4-10.12.10 מחווה למייק לי המעגל הפנימי Mike Leigh Tribute – הקרנות מיוחדת Inside Job – Special Screenings 18-19.12.10 שבוע הקולנוע מועדון הסרט המופרע הקרואטי - הומור יהודי, וודי אלן Croatian Film Week ו'ימי הרדיו' Wacky Film Club - Jewish Humor, Woody Allen and Radio Days 9.12.210 פסטיבל הולגאב כמו מלכת אנגליה ליצירה אתיופית- – הקרנות מיוחדות ישראלית Just Like the Queen of England – Special Hullegeb Festival for Screenings Ethiopian-Israeli Arts קרן ירושלים, קרן ון ליר, קרן אוסטרובסקי, עיריית ירושלים, משרד התרבות The Jerusalem Foundation, The Van Leer Group Foundation, Ostrovsky Family Fund, Jerusalem Municipality, Ministry of Culture רכישת כרטיסים מכירת כרטיסים לקהל הרחב (שאינם מנויים) תתאפשר במהלך היום דרך אתר מנויים יקרים האינטרנט שלנו בכתובת: www.jer-cin.org.il, וכן שעה לפני תחילת ההקרנה הראשונה בכל ימות השבוע ועד תחילת הסרט האחרון. בימי שישי תפתח הקופה כשעה לפני תחילת כל סרט. הזמנת כרטיסים: 4330 565 02 למנויים: 4330 565 02. חניה לבאי הסינמטק מול מלון הר ציון כרטיסים למנויים יישמרו עד 10 דקות לפני תחילת ההקרנה בלבד! החודש בסינמטק This Month at the Cinematheque החודש בסינמטק This -

Photographic Boxes – Art Installations: a Study of the Role of Photography in the Israel Pavilion at Expo

Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 26, 2018 121 Tal-Or Ben-Choreen Photographic Boxes – Art Installations: A Study of the Role of Photography in the Israel Pavilion at Expo ‘67 Tal-Or Ben-Choreen / Photographic Boxes – Art Installations: A Study of the Role 122 of Photography in the Israel Pavilion at Expo 67 Expo ‘67 in Montreal marked the second international exhibition that Israel partic- ipated in after its first foray at the World’s Fair in Brussels in 1958.1 Israel’s Pavilion in Brussels was deemed unsuccessful by the ‘67 organizers, and the country hoped that the Montreal event would mark a shift in the reception of the country’s repre- sentation.2 The implications of constructing such a pavilion during this period are important to consider. For the young nation, the half-million-dollar fee required for the Pavilion was not easy to obtain.3 Yaacov Yannai, the general manager of the Pavilion, explained that the exhibition committee knew early on they could not com- pete with the large budgets of the other pavilions. However, Yannai felt the pressing political climate in the region and the socio-cultural significance of Israel meant that it had a powerful story to share with the world.4 As such, instead of commem- orating the State since its inception in 1948 as was done with the Brussels Pavilion, the organizers decided that the most relevant theme for the Montreal World’s Fair was the history of the Jewish people.5 The Israel Pavilion in Montreal would there- fore address this history spanning over two thousand years, merging ancient and contemporary times.