The Foundations of a New World Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Boardgamer Magazine

Volume 9, Issue 3 July 2004 The BOARDGAMER Sample file Dedicated To The Competitive Play of Avalon Hill / Victory Games and the Board & Card Games of the World Boardgame Championships Featuring: Puerto Rico, 1776, Gunslinger, Victory In The Pacific, Naval War, Panzerblitz / Panzer Leader and AREA Ratings 2 The Boardgamer Volume 9, Issue 3 July 2004 Current Specific Game AREA Ratings To have a game AREA rated, report the game result to: Glenn Petroski; 6829 23rd Avenue; Kenosha, WI 53143-1233; [email protected] March Madness War At Sea Roborally 48 Active Players Apr. 12, 2004 134 Active Players Apr. 1, 2004 70 Active Players Feb. 9, 2004 1. Bruce D Reiff 5816 1. Jonathan S Lockwood 6376 1. Bradley Johnson 5439 2. John Coussis 5701 2. Ray Freeman 6139 2. Jeffrey Ribeiro 5187 3. Kenneth H Gutermuth Jr 5578 3. Bruce D Reiff 6088 3. Patrick Mitchell 5143 4. Debbie Gutermuth 5532 4. Patrick S Richardson 6042 4. Clyde Kruskal 5108 5. Derek Landel 5514 5. Kevin Shewfelt 6036 5. Winton Lemoine 5101 6. Peter Staab 5489 6. Stephen S Packwood 5922 6. Marc F Houde 5093 7. Stuart K Tucker 5398 7. Glenn McMaster 5887 7. Brian Schott 5092 8. Steven Caler 5359 8. Michael A Kaye 5873 8. Jason Levine 5087 9. David Anderson 5323 9. Andy Gardner 5848 9. David desJardins 5086 10. Dennis D Nicholson 5295 10. Nicholas J Markevich 5770 10. James M Jordan 5080 11. Harry E Flawd III 5248 11. Vince Meconi 5736 11. Kaarin Engelmann 5078 12. Bruno Passacantando 5236 12. -

Guadacanal Symposium V1.Indd

Symposium Program BB’s Stage Door Canteen Symposium Speaker Books To order your books before the Symposium, 7:30 a.m. – 8:30 a.m. visit www.SHOPWWII.org or call 1-504-528-1944 X 244. Arrival and Registration Use promo code TRAVELVIP to save 10%. 8:30 a.m. – 8:45 a.m. Welcome and Opening Remarks – Robert M. Citino, PhD, Moderator 8:45 a.m. – 9:30 a.m. Session 1 – The Road to Guadalcanal / The Solomons –Richard Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle 9:30 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Break and Book Signing 10:00 a.m. – 10:45 a.m. Session 2: Land –Andrew Wiest, PhD, The Pacific War: Pearl Harbor, Singapore, Midway, Guadalcanal, Philippines Sea, Iwo Jima 10:45 a.m. – 11:15 a.m. Break and Book Signing RICHARD FRANK ANDREW WIEST, PhD JIM HORNFISCHER 11:15 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. Guadalcanal The Pacific War Neptune’s Inferno Session 3: Sea Item #3189 Item #22649 Item #15461 –Jim Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The US Navy at Guadalcanal $25.00 $34.95 $35.00 12:00 p.m. – 1:15 p.m. Break, Book Signing, and Lunch 1:15 p.m. – 2:00 p.m. Session 4: Air –Stephen L. Moore, The Battle for Hell’s Island: How a Small Band of Carrier Dive-Bombers Helped Save Guadalcanal 2:00 p.m. – 2:30 p.m. Break and Book Signing 2:30 p.m. – 3:15 p.m. Session 5: Lessons Learned –Trent Hone 3:15 p.m. -

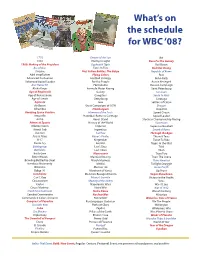

What's on the Schedule For

What’s on the schedule for WBC ‘08? 1776 Empire of the Sun Ra! 1830 Enemy In Sight Race For the Galaxy 1960: Making of the President Euphrat & Tigris Rail Baron Ace of Aces Facts In Five Red Star Rising Acquire Fast Action Battles: The Bulge Republic of Rome Adel Verpflichtet Flying Colors Risk Advanced Civilization Football Strategy Robo Rally Advanced Squad Leader For the People Russia Besieged ASL Starter Kit Formula De Russian Campaign Afrika Korps Formula Motor Racing Saint Petersburg Age of Empires III Galaxy San Juan Age of Renaissance Gangsters Santa Fe Rails Age of Steam Gettysburg Saratoga Agricola Goa Settlers of Catan Air Baron Great Campaigns of ACW Shogun Alhambra Hamburgum Slapshot Amazing Space Venture Hammer of the Scots Speed Circuit Amun-Re Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage Squad Leader Anzio Here I Stand Stockcar Championship Racing Athens & Sparta History of the World Successors Atlantic Storm Imperial Superstar Baseball Attack Sub Ingenious Sword of Rome Auction Ivanhoe Through the Ages Axis & Allies Kaiser's Pirates Thurn & Taxis B-17 Kingmaker Ticket To Ride Battle Cry Kremlin Tigers In the Mist Battlegroup Liar's Dice Tikal Battleline Lost Cities Titan BattleLore Manoeuver Titan Two Bitter Woods Manifest Destiny Titan: The Arena Brawling Battleship Steel March Madness Trans America Breakout Normandy Medici Twilight Struggle Britannia Memoir '44 Union Pacific Bulge '81 Merchant of Venus Up Front Candidate Monsters Ravage America Vegas Showdown Can't Stop Monty's Gamble Victory in the Pacific Carcassonne Mystery of the -

Century Events 51

Century Events 51 2011 Results 2011 Results Steven LeWinter, NC Ed Paule, NJ Nick Page, on Charles Drozd, IL Rob Flowers, MD Andy Gardner, VA O J. Oppenheim, VA Jim Kramer, PA O Mark Love, MD Jim Eliason, IA O David Duncan, PA Ed Menzel, CA Eric Freeman, PA Charles Drozd, IL 94 2008-2011 36 1991-2011 Top Laurelists Top Laurelists Eric Freeman, PA 48 Andy Gardner, VA 342 Nick Page, on 36 Dan Henry, IL 272 Andrew Gerb, MD 33 Michael Kaye, CA 246 Steven LeWinter, NC 30 Ed Menzel, CA 232 Randy Buehler, WA 30 Charlie Drozd, IL 188 Sceadeau D’Tela, NC 18 Darren Kilfara, uk 146 Rob Flowers, MD 12 Ed Paule, NJ 126 Matt Peterson, MN 12 Michael Ussery, MD 118 Steven LeWinter, NC Scott Chupack, IL 12 Ed Paule, NJ John Pack, CO 114 Kevin Brown, GA 12 Alan Applebaum, MA 113 Vegas Showdown (VSD) Victory in the Pacific (VIP) espite being out of print, 2011 was VSD’s most he bids increased from 4.5 to 4.8, Dsuccessful year in its fourth outing at WBC. Tand the Japanese winning percent- Thanks to Bob Wicks, Mohegan Sun, a Connecticut age dropped eight points, but remained casino, sponsored the event with prize support in the a very strong 60%. After five rounds, Jim Eliason form of a T-shirt and deck of cards for each player. was the only unbeaten player—no doubt yearning The three heats produced 29 games, from which, for a return to the days of the last man standing Alex Bove and defending champion Randy Bue- swiss format. -

D-Day: the Invasion of Normandy and Liberation of France Spring and Fall 2020

Book early and save $1,000 per couple! See page 10 for details. Bringing history to life D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy and Liberation of France Spring and Fall 2020 Normandy Beaches • Arromanches • Sainte-Mère-Église Bayeux • Caen • Pointe du Hoc • Falaise NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Friend of the Museum, One of the most inspiring moments during my 17 years with the Museum was visiting Omaha Beach in 2005 with WWII veteran Dr. Hal Baumgarten, who landed there with the 116th Infantry Regiment as part of the first wave on D-Day and was wounded five times in just 32 hours. Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the very places where these events unfolded and hear the words of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of this Museum since we first opened our doors on June 6, 2000, and while our mission has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II, we still hold our Normandy travel programs in special regard—and consider them the very best in the market. Drawing on our historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s highly regarded D-Day tours take visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed so much to pull off the greatest amphibious attack in history and ultimately secure the freedom we enjoy today. -

D-Day: the Invasion of Normandy and Liberation of France

Book early and save! Worry-Free booking through December 31, 2021. See inside for details. Bringing history to life D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy and Liberation of France Normandy Beaches • Arromanches • Sainte-Mère-Église Bayeux • Caen • Pointe du Hoc • Falaise THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL PROGRAM Stephen J. Watson, President & CEO, Travel to The National WWII Museum Museum Dear Friend of the Museum, Quick Facts 27 One of the most inspiring moments during my 18 years with the Museum was visiting 5 countries covering Omaha Beach in 2005 with WWII veteran Dr. Hal Baumgarten, who landed there with the 116th Infantry Regiment as part of the first wave on D-Day and was wounded five 8 million+ all theaters times in just 32 hours. visitors since the Museum of World War II opened on June 6, 2000 Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the very places where these events unfolded and hear the words of those who fought there. $2 billion+ Tour Programs operated The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of this in economic impact on average per year, at Museum since we first opened our doors on June 6, 2000, and while our mission has times accompanied by expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II, we still hold our Normandy travel programs in special regard—and consider them the very best in the 160,000+ 30 WWII veterans market. active Museum members Drawing on our historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s travelers, highly regarded D-Day tours take visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable 8,000+ Overseas journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du representing every US state Visit American Battle Hoc. -

Storm Over Arnhem

Volume 19, Number 1 R.MacGowan 2 *The AVALON HILL CiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiAiiiiiiiViiiiiiiaiiiiiiilOiiiiiiiniiiiiiiHiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiliiiiiiilPiiiiiiihiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiloiiiiiiisiiiiiiiOiiiiiiiPhiiiiiiiYiiiiiiiPiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiariiiiiiitiiiiiii9iiiiiiiliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii;;;;;;.JII GENERAL As of April 1982, the needs and wishes of the experienced in virtually every aspect of the in The Game Players Magazine hard-core wargaming public have been addressed dustry. An initial schedule, covering the first year of with the advent of the New York-based Victory operations, includes forays into contemporary and The Avalon HIli GENERAL is dedicated to the presenta Games, Inc. At first concerned exclusively with the World War II conflicts, science fiction, and role tion of authoritatIVe articles on the strategy. taclics, and variation of Avalon Hill wargames. Historical articles are design, development, and promotion of its quality playing. Initial design conferences have already Included only insomuch as they provide useful background wargame-oriented line, Victory Games will in the taken place for several of these products, and work information on current Avalon Hill titles. The GENERAL is future expand into the areas of science fiction, role is underway to devise new systems both for new published by the Avalon Hill Game Company solely for tne playing, and computer games. The firm will rely topics and for subjects whose popular appeal cultural edification of the serious game aficionado, in the hopes of improving the game owner's proficiency of play and heavily on its parent company, Monarch-Avalon, to seems never to diminish throughout the hobby. providing services nOI otherwise available to the Avalon Hill provide administrative and service support. The The staff of Victory Games includes four of the game buff. Avalon Hill IS a division of Monarch Avalon "think-tank" atmosphere and concentration of most respected designers in the field. -

Capturing the Year — 2009 Distillation of Years of Research, Is Represented in Capturing the Year

Capturing the Year 2009 WRITINGS FROM THE ANU COLLEGE OF ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Edited by Barbara Nelson with Andrew MacIntyre ANU COLLEGE OF ASIA & THE PACIFIC Capturing the Year Writings2009 from the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific Edited by Barbara Nelson with Andrew MacIntyre ANU COLLEGE OF ASIA & THE PACIFIC Capturing the year ISSN 1836-3784 (Print) ISSN 1836-3792 (Online) Published by ANU College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/ Produced by Minnie Doron Printed in Canberra by The Australian National University Printing Service Contents Introduction vii Climate Change Frank Jotzo, New government, new attitude, new optimism 1 Ross Garnaut, Everyone must do their bit 3 Will Steffen, Climate change: the risks of doing nothing 7 Raghbendra Jha, India and the Copenhagen summit 10 Stephen Howes, Can China rescue the world climate change negotiations? 13 Democracy Benjamin Reilly, Big task to tackle at Bali forum 17 Assa Doron, Speaking of Israel 20 Human Rights and Ethics Hilary Charlesworth, Debate, not a boycott, needed to address racism 23 Luigi Palombi, Who owns your genes? 26 Nicholas Cheesman, Shameful responses to UN rights expert should be binned 29 Language Edward Aspinall, Lost in translation 32 Jamie Mackie, Don’t overlook Indonesian 38 Kent Anderson and Joseph Lo Bianco, Speak, and ye shall find knowledge 40 Resources and Energy Quentin Grafton, One fish, two fish, no fish 44 Robert Ayson, Nuclear energy is neither a monster nor a panacea 51 Afghanistan -

Major Fleet-Versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Second Ed

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Historical Monographs Special Collections 2016 HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945 Milan Vego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs Recommended Citation Vego, Milan, "HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945" (2016). Historical Monographs. 22. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs/22 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Monographs by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 War, Pacific the in Operations Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Milan Second Ed. Second Also by Milan Vego COVER Units of the 1st Marine Division in LVT Assault Craft Pass the Battleship USS North Carolina off Okinawa, 1 April 1945, by the prolific maritime artist John Hamilton (1919–93). Used courtesy of the Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C.; the painting is currently on loan to the Naval War College Museum. In the inset image and title page, Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance ashore on Kwajalein in February 1944, immediately after the seizure of the island, with Admiral Chester W. -

PRE-CONS for EARLY ARRIVALS in 2015! Paths of Glory Hannibal

1775 Hannibal Victory In Paths of Rebellion the Pacific Glory August 1 August 1 - 2 August 2 - 4 August 1 - 4 2 PM 1 PM start 9 AM start 3 PM start August 3 August 9 Lancaster Host, Lancaster, PA [ ] WBC: I enclose check or money order made payable to BPA to register for WBC 2015. Registration fee is based on date of arrival. Badges dispensed before order date are subject to a $20 surcharge per day. Payment accompanying registration must be received no later than June 30, 2015. Thereafter, higher fees apply. [ ] TRIBUNE membership $100 - Includes 2015 Patron listing, free admission to WBC and all of its events including Pre-Cons (August 1 - 9). [ ] SUSTAINING membership - $80 - Includes free admission to WBC and all of its Monday thru Sunday events (August 3 - 9). [ ] PRE-PAID 2015 Sustaining or Tribune memberships - $0 All rates paid at-the-Door add $20. Pre-register before June 30 for lowest cost. [ ] Tue-Sun $70 [ ] Wed-Sun $60 [ ] Thur-Sun $50 [ ] Fri-Sun $40 [ ] Sat-Sun $30 [ ] WBC 2014-15 full color Yearbook: $10 [ ] Any one day: $20 (plus $10 per additional day - specify day): ____________ For Pre-Con info, see: boardgamers.org/yearbkex15/precon.htm [ ] 2015 WBC silk-screen Souvenir T-Shirts: $15 each; add $5 for sizes 2X, 3X Size: _____ S, M, L, XL, 2X, 3X _____ Hat: $15 Duffle Bags: $40 each _____ Colors: Black, Red, Forest Green, Royal Blue, Navy Blue _____ Duffle Bag Orders Must be received by June 15. See boardgamers.org/wbc/souvenirs.htm Total: ______ SUMMARY: By submitting this form, I understand that neither the BPA nor any of its directors, officers, members, employees or agents are responsible for any personal injury of any kind or any lost or misplaced items while I attend WBC. -

THE G EN CON'xiv Convention Caugusi

THE G EN CON'XIV coNvENTION cAugusi- 1.5-16'61.981 PROGRAM at SCHEDULE OF EVENTS- U_WPARKSIDE Oen Con' and -the Gen ConComyass Logo are registered Service marks of TSIZI-tobbics,Iac. THE GEN CON° XIV (about 150 yards south of the main com- GAME CONVENTION AND plex). TRADE SHOW The Student Union contains the two cam- AUGUST 13.16, 1981 pus cafeterias (one fast food type and a tra- INFORMATION BROCHURE ditional cafeteria), a 400 seat theatre, and a recreation room with a twelve lane bowling The Gen Con Game Convention is the alley, pool tables, ping pong tables, foosball We've taken the oldest in America, dating back to 1967, tables, and pinball machines. when a group of garners from the Milwau- Dungeons & Dragons game kee-Chicago area got together for a week- end devoted to nothing but gaming. They all Convention Registration out of the Dark Ages. enjoyed it so much that in 1968 they decid- ed to invite everyone for the fun; the result Fees was the Gen Con I Game Convention—a At the door, 4 days $15.00 one day event which, despite its short dura- At the door, 3 days $15.00 tion, drew hobbyists from both the East and At the door, 2 days $12.00 West Coasts, Texas and Canada. From that At the door, 1 day $ 7.00 beginning the Gen Con Game Fair has grown as a national convention year by year Upon paying the convention registration —and when the International Federation of fee you are entitled to: Wargaming was no longer able to sponsor 1. -

Conflict Simulation Comment and Analysis

GOLDEN ANNIVERSARY VOLUME Celebrating 50 Years of Service and Participation in the Wargaming Community Volume 50, Issue 6 December 2015 The Kommandeur : Conflict Simulation Comment and Analysis From the President Kenneth Oates From the Editor This marks the sixth and final issue for this year. For many years I have been collecting games. We are ending this year with several unresolved is- Some I actually play. However I feel it is time to get sues, more of which you will find below. Also in rid of most of them. Some are well worn, some are this issue you will find the latest Treasurer’s report. still in shrink wrap. They are listed on pages 22 Here is a summary of items of interest. through 29. To help with the postage, I will ask $2 a It was announced a few weeks ago that AHIKS game (I will ask $3 for the larger games). Contact member Cory Wells passed away. He was very ac- me with your choices. When I determine what I can tive on our Consimworld page, posting many ques- send you, I will let you know the cost. If you live tions and comments there. He will be missed. outside the U.S., we will have to discuss postage. It is also my duty to announce that Charles Mar- Contact me as soon as you have made your choice. I shall informed the Executive that due to his com- will be away most of December, so I do not expect puter upgrade, he will not be able to continue as to ship any games until January.