The Corrib Gas Dispute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST Sheila On

1 . APRIL 9, 2006 . THE SUNDAY TIMES 6 NEWS McCaffrey, left, says her training with Quinn, right, was an ‘absolute transformation’ that led ultimately to her company striking oil in the Central American state of Belize Has mind guru’s teaching paid off in giant oil strike? WAS it a case of mind over mat- 1950s to the 1990s of hundreds Kerrygold, which has to be John Briceno, Belize’s minister ter? A tiny company set up by Enda Leahy of millions of dollars.” 25 miles refined,” said McCaffrey. “The of natural resources, calculates two Irish women and three geol- Quinn’s philosophy, which quality of their oil is just 15-25 that at current prices the govern- ogists in 2002 has struck oil in quit the country in disappoint- promotes what he calls “mind API [a measurement of oil ment’s take from even small- Belize, with the help of contro- ment after failing to find a technology”, has been criticised MEXICO purity]. Here we’re sitting on scale pumping of around versial lifestyle guru Tony gusher, but BNE scored three as brainwashing but is oil which is closer to 40. To get 60,000 bpd would fund the Quinn. times in its first three attempts, defended by adherents as posi- an idea of what that means, die- country’s budget. Succeeding where multi- and the government believes it tive and life-changing. sel in a refined state is 42.” “If we could produce even billion dollar corporations had could soon be producing Complaints about Quinn’s Belize Producers in surrounding 20,000 bpd, you can imagine City failed, the company has found 20,000 barrels of oil per day techniques have come from the G countries have only discovered what we could do with that,” he commercial quantities of high- (bpd). -

Shell E&P Ireland

Shell E&P Ireland Ltd Offshore Supplementary Update Report 3 CONSTRUCTION 3.1 Construction Methods and Sequence The Construction Strategy for the offshore field and pipeline is described in the 2001 Offshore EIS. Some construction activities have taken place since 2001, including the installation of the export pipeline from the Corrib Field to the landfall at Glengad, however there are still a number of outstanding activities to be completed. Installation of the pipeline commenced in 2008 using methods described in the 2001 Offshore EIS. Further details of installation methods for a number of components yet to be installed are now available and are described below, along with an updated schedule. 3.2 Construction Sequence Activities carried out since 2001 on the offshore pipeline route, including the landfall, include the following: • 2002: Glengad Headland landfall site: Most of the topsoil stripping (approximately 80%) undertaken, to a distance of 50m landward of the cliff. A section of the cliff was cut to access the beach and intertidal zone. Following suspension of construction work, the landfall site and the cliff were reinstated. Nearshore and intertidal trench Broadhaven Bay: Intertidal causeway was constructed. Part of the trench was excavated and subsequently reinstated using the extracted rock and sand. Causeway was removed. • 2005: Glengad Headland: Temporary construction site established. Following suspension of works the area was reinstated. Nearshore Trench: The outer reinstated section of the near-shore trench was excavated and later backfilled. • 2006 – 2008: Corrib Field: Wells completed and Christmas trees installed, new wells drilled, well protection structures and infield flowlines installed, pipeline manifold protection structure installed. -

Royal Dutch Shell and Its Sustainability Troubles

Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 Albert ten Kate May 2011 1 Colophon Title: Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 May 2011. This report is made on behalf of Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) Author: Albert ten Kate, free-lance researcher corporate social responsibility Pesthuislaan 61 1054 RH Amsterdam phone: (+31)(0)20 489 29 88 mobile: (+31)(0)6 185 68 354 e-mail: [email protected] 2 Contents Introduction 4 Methodology 5 Cases: 1. Muddling through in Nigeria 6 1a) oil spills 1b) primitive gas flaring 1c) conflict and corruption 2. Denial of Brazilian pesticide diseases 14 3. Mining the Canadian tar sands 17 4. The bitter taste of Brazil's sugarcane 20 4a) sourcing sugarcane from occupiers of indigenous land 4b) bad labour conditions sugarcane harvesters 4c) massive monoculture land use 5. Fracking unconventional gas 29 6. Climate change, a business case? 35 7. Interfering with politics 38 8. Drilling plans Alaska’s Arctic Ocean 42 9. Sakhalin: the last 130 Western Gray Whales 45 10. The risky Kashagan oil field 47 11. A toxic legacy in Curaçao 49 12. Philippines: an oil depot amidst a crowd of people 52 3 Introduction Measured in revenue, Royal Dutch Shell is one of the biggest companies in the world. According to its annual report of 2010, its revenue amounted to USD 368 billion in 2010. Shell produces oil and gas in 30 countries, spread over the world. -

2005 Annual Report on Form 20-F

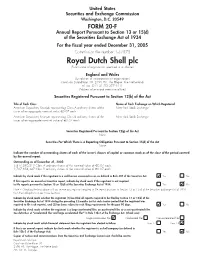

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2005 Commission file number 1-32575 Royal Dutch Shell plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organisation) Carel van Bylandtlaan 30, 2596 HR, The Hague, The Netherlands tel. no: (011 31 70) 377 9111 (Address of principal executive offices) Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered American Depositary Receipts representing Class A ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value €0.07 each American Depositary Receipts representing Class B ordinary shares of the New York Stock Exchange issuer of an aggregate nominal value of €0.07 each Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act None Securities For Which There is a Reporting Obligation Pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. Outstanding as of December 31, 2005: 3,817,240,213 Class A ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. 2,707,858,347 Class B ordinary shares of the nominal value of €0.07 each. Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Lessons Not Learned the Other Shell Report 2004 Dedicated to the Memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa

Lessons Not Learned The Other Shell Report 2004 Dedicated to the memory of Ken Saro-Wiwa “My lord, we all stand before history. I am a man of peace. Appalled by the denigrating poverty of my people who live on a richly-endowed land . anxious to preserve their right to life and to a decent living, and determined to usher into this country . a fair and just democratic system which protects everyone and every ethnic group and gives us all a valid claim to human civilization. I have devoted all my intellectual and material resources, my very life, to a cause in which I have total belief and from which I cannot be blackmailed or intimidated. I have no doubt at all about the ultimate success of my cause . Not impris- onment nor death can stop our ultimate victory.” —Ken Saro-Wiwa’s final statement before his execution on 10 November 1995 Guide to contents 1 Guide to contents 2 Foreword from Tony Juniper & Vera Dalm This report is based largely on evidence from people Tony Juniper, Executive Director, Friends of the Earth (England, around the world who live in the shadows of Shell’s vari- Wales & Northern Ireland) & Vera Dalm, Director, Milieudefensie ous operations. This report is written on behalf of (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) Friends of the Earth (FOE); Advocates for Environmental Human Rights; Coletivo Alternative Verde; Community In- 3 The Year in Review power Development Association; Concerned Citizens of Norco; Environmental Rights Action (FOE Nigeria); 4 Niger Delta, Nigeria Global Community Monitor; groundWork (FOE South Injustice as a Shell Trademark Africa); Humane Care Foundation Curacao; Louisiana Bucket Brigade; Niger-Delta Project for the Environment, 7 Durban, South Africa Human Rights and Development; Pacific Environment Communities Doomed with Aging Refinery Watch; Sakhalin Environment Watch; Shell to Sea; South Durban Community Environmental Alliance; and 10 Sao Paulo, Brazil United Front to Oust Oil Depots. -

Biodiversity Action Plan

CORRIB DEVELOPMENT BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN 2014-2019 Front Cover Images: Sruwaddacon Bay Evening Lady’s Bedstraw at Glengad Green-veined White Butterfly near Leenamore Common Dolphin Vegetation survey at Glengad CORRIB DEVELOPMENT BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN 1 Leenamore Inlet CORRIB DEVELOPMENT 2 BIODIVERSITY ACTION PLAN LIST OF CONTENTS 2.4 DATABASE OF BIODIVERSITY 39 3 THE BIODIVERSITY A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 ACTION PLAN 41 FOREWORd 5 3.1 ESTABLISHING PRIORITIES FOR CONSERVATION 41 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 3.1.1 HABITATS 41 1 INTRODUCTION 8 3.1.2 SPECIES 41 1.1 BIODIVERSITY 8 3.2 AIMS 41 1.1.1 WHAT is biodiversity? 8 3.3 OBJECTIVES AND acTIONS 42 1.1.2 WHY is biodiversity important? 8 3.4 MONITORING, EVALUATION 1.2 INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL CONTEXT 9 AND IMPROVEMENT 42 1.2.1 CONVENTION on BIODIVERSITY 9 3.4.1 MONITORING 42 1.2.2 NATIONAL and local implementation 9 3.4.2 EVALUATION and improvement 43 1.2.3 WHY A biodiversity action plan? 10 TABLE 5 SUMMARY of obJECTIVES and actions for THE conservation of habitats and species 43 3.4.3 Reporting, commUNICATING and 2 THE CORRIB DEVELOPMENT VERIFICATION 44 AND BIODIVERSITY 11 3.4.3.1 ACTIONS 44 2.1 AN OVERVIEW OF THE CORRIB 3.4.3.2 COMMUNICATION 44 DEVELOPMENT 11 3.5 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT AND FIG 1 LOCATION map 11 PARTNERSHIPS FOR BIODIVERSITY 44 FIG 2 Schematic CORRIB DEVELOPMENT 12 3.5.1 S TAKEHOLDER engagement and CONSULTATION 44 2.2 DESIGNATED CONSERVATION SITES AND THE CORRIB GaS DEVELOPMENT 13 3.5.2 PARTNERSHIPS for biodiversity 44 3.5.3 COMMUNITY staKEHOLDER engagement 45 2.2.1 DESIGNATED -

The Corrib Gas Tunnel >>>

The Corrib Gas Tunnel >>> Contents > The Corrib Tunnel > The Aughoose and Glengad sites > BAM Civil/Wayss & Freytag Joint Venture > A brief history of tunnelling > ‘Fionnuala’ – the Corrib TBM > Tunnelling traditions > How does the TBM work? > The TBM operator > Maintaining the tunnel > Installation of the pipeline & reinstatement 1 The Corrib Tunnel The onshore pipeline is the final phase of the Corrib gas project to be completed. The onshore pipeline section is 8.3km long and 4.9km of this will be installed in a tunnel, 5.5m the majority of which will run under Sruwaddacon Bay, in north Mayo. The tunnel will have an external diameter of 4.2m and an internal 12m diameter of 3.5m and will run at depths of between 5.5m and 12m under Sruwaddacon Bay. The building of the tunnel requires 4.2m 3.5m the use of a large tunnel boring machine (TBM). “This will be the longest tunnel in Ireland and 2 the longest gas pipeline 3 tunnel in Europe” “The rock, sand and gravel from the TBM is pumped back through the tunnel to Aughoose” “The compound has been surrounded by a visual barrier and an acoustic fence” The Aughoose and Glengad sites Excavation of the tunnel is in one direction, starting at a launch shaft The compound at Aughoose contains all of the services and Aughoose compound was designed and constructed to limit its site water treatment plant where the water discharges into on a SEPIL-owned site in the townland of Aughoose and running to a materials needed for the tunnelling process. -

The Great Gas Giveaway

Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 1 The Great Gas Giveaway How the elites have gambled with our health and wealth An Afri Report Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 2 Andy Storey and Michael McCaughan Giving Away The Gas 26/05/2009 17:31 Page 3 Giving away the gas “We gave the Corrib gas away and now Éamon Ryan is intent on giving away the remaining choice areas of our offshore acreage at less than bargain basement prices”. 1 An international study in 2002 found that only Cameroon took a lower share of the revenues from its own oil or gas resources than Ireland – the vast majority of countries demand that multinational oil and gas companies pay the state proportionately twice the amount that the Irish government is extracting from the Shell-led consortium that is exploiting the Corrib gas field. Ghana, for example, insists that the state-owned Ghanaian National Petroleum Corporation has a 10 per cent ownership stake in any resource find and the multinationals are also liable to a 50 per cent profits tax. Ireland, by contrast, demands no state shareholding in any resource finds, nor does it demand royalty payments. A generous (to the companies) tax rate of only 25 per cent applies – and even that low tax rate only kicks in after a company’s exploration and development costs (and the estimated costs of closing down the operation when the resources are depleted) have been recovered.2 The Corrib gas field will probably be half depleted before any tax is paid at all. -

The Corrib Debacle

1. THE CORRIB DEBACLE – WHY IRELAND IS COMPLETELY OFF LIMITS FOR INVESTMENT 1.1 The background to the debacle Natural gas generates over 60% of the electricity in Ireland and fuels homes and industry. While the Kinsale Field was discovered and developed in the early seventies, gas from the European network is currently pumped into the reservoir there over the summer and drawn out over the winter months. Very little is drawn any more from the field itself. Indeed a single gas pipeline from the European grid goes to a compressor station in South Western Scotland and then is routed under the Irish Sea to North of Dublin. The country is hanging off that pipe! Ireland has not had a good innings with petroleum exploration. About 150 exploration wells have been drilled in the Irish Sector, outside of Kinsale Field we had to wait until 1996 until Enterprise Energy Ireland finally hit pay dirt with the Corrib Natural Gas Field. Note: Shell Exploration and Production Ireland Ltd (SEPIL) acquired Enterprise Energy Ireland in 2002. A pretty poor run from exploration in Irish waters, in particular given that a drilling rig costs about €0.6 million per day and the success ratio in the North Sea sector is about one producing field for every four exploration wells drilled. 1 Bit of a difference in petroleum finds in North Sea and Irish waters. However, many Irish are insistent that the same exploration terms should apply in both jurisdictions. The Corrib field is marginal by international standards; the well head is 80 km off the exposed North Western Coast and at a depth of 300 m. -

WHO's WHO Shell Brian Foley, Contracts Manager, Corrib Project

OSSL SHELL CORRIB SAGA - WHO'S WHO Shell Brian Foley, Contracts Manager, Corrib Project: [email protected] Julia Busby, Head of Shell Legal: [email protected] Frances van Dam, from Shell's business integrity department: [email protected] Charles Hornsby, Ethics and Compliance Officer at Shell Downstream [email protected] Bridgit Lowe, head of Shell Legal, Ireland [email protected] John Gallagher: [email protected] (Exec VP Shell Global Upstream) Alan Mee: Assistance Mayo Manager: [email protected] Ann Hamilton, Shell Corrib Financial Director: [email protected] Wim-Peter Vanbel, [email protected] (regional head Business Integrity Dept Europe & Russia Christy Loftus, Shell Ireland Communications: Christy Loftus [email protected] Michiel Brandjes, Company Sec. & General Counsel: [email protected] Agnes Mclaverty, Permits and Consents Manager for Shell E&P Ireland Limited: [email protected] Mary Barrett, Emergency Response Co-Ordinator Shell [email protected] Peter Voser, RDS PIc CEO: [email protected] Conner Byrne, Shell EP Ireland" (said to have demanded that invoices be falsified and diverted to Roadbridge to avoid any direct connection with Shell - also said to have threatened that OSSL would never work again in oil and gas industry if it revealed any of the activity) Terry Nolan, former CEO, Shell E&P Ireland Michael Crothers, CEO Shell E&P Ireland: [email protected] (said to have "personally felt some moral obligation ..." ) Roadbridge (Main Contractor on Corrib Project?) OSSL people Desmond Kane: [email protected] Amanda Kane Neil Rooney: [email protected] OSSL Supporter/agent/employee? - GEORGE HAMILTON George Hamilton: georgehamiltoneollve.ie Sent email in support of OSSL to Shell to Sea, also made several postings on our "Shell Blog", all supportive of OSSL. -

Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Ireland Financing Climate Chaos

Fossil fuel subsidies in Ireland Financing Climate Chaos Citizens for Financial Justice project March 2020 Author: Clodagh Daly 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………….8 1. Natural gas 1. ‘Meet the new boss, same as the old boss’: the myth of natural gas as a transition fuel……………………………………………………………………………….10 2. Box 1: Shaping transition narratives……………………………………………..12 3. A ‘leisurely’ climate emergency? Natural gas in the Irish policy context……….13 2. Subsidies 1. What is a ‘subsidy’? Overcoming ambiguous definitions……………………….18 2. The case for removing natural gas production subsidies……………………...…20 3. Case studies 1. Public finance as a pillar for natural gas infrastructure………………………….25 2. Tax exemptions, i.e. ‘fossil fuel welfare’………………………………………..31 3. Investments by State-owned enterprises…………………………………………35 4. Fiscal support…………………………………………………………………….41 4. Conclusion and recommendations……………………………………………………….45 5. Annex…………………………………………………………………………………….47 Executive summary Natural gas is a highly potent fossil fuel consisting of mostly methane gas that can trap heat up to 86 times more efficiently than carbon dioxide in a 20-year period. According to the IPCC, there is no pathway to remain within 1.5°C that is compatible with natural gas expansion.1 However, the fossil fuel industry presents energy interests as a critical element of Ireland’s transition. Irish energy and climate policy describe gas as a ‘transition’ fuel whose share in the energy mix is consistent with Ireland’s climate objectives.2 Conversely, a central element of a transition underpinned by science and climate justice requires governments to make financial flows and energy investments ‘consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’ in accordance with Article 2.1c of the Paris agreement. -

E Corrib Gas Project: the Deposition of 450,000 Tonnes of Peat

PEAT IN ENERGY e Corrib gas project: the deposition of 450,000 tonnes of peat B. Moyles Bord na Móna Energy Ltd, Leabeg, Tullamore, Co. Offaly, Ireland Phone: +353-87-9612077, e-mail: [email protected] Summary As part of Shell’s Corrib gas project to construct an onshore gas terminal at Bellanaboy, North-west Mayo, Ireland it was necessary to remove approximately 450,000 m³ of peat from the terminal footprint. The excavation works were carried out by a civil engineering contractor (Roadbridge Ltd.) and this excavated peat was then transported by a road haulier (Iggy Madden Transport Ltd.) a distance of 11km by road to a specially constructed deposition site owned and operated by Bord na Móna. This peat deposition site, where the removed peat was received, re-loaded for internal site haulage and finally placed, is located on industrial cutaway peatlands in Srahmore, near Bangor-Erris in Co. Mayo, Ireland. The peat deposition process was included as part of the planning application for Shell E&P Ireland Ltd (SEPIL) to construct a gas terminal for the reception and separation of gas from the Corrib gas field. The deposition was governed by numerous planning conditions, also separate conditions imposed as part of the waste licence as issued by the EPA. The peat was received at Srahmore and spread over low areas (bays) to depths of on average 1.4m - 1.8m. The deposited peat was then profiled allowing for water run off. Following deposition activities and the im - plementation of the agreed monitoring programme vegetation was allowed to establish naturally, primarily soft rush ( Juncus effusus ) as well as other native peatland species.