NRN Newsletter13 English.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Bald Eagles 101 Name ______

Bald Eagles 101 Name __________________________ Go to the Science Spot (http://sciencespot.net/) and click “Kid Zone” to find the link for the “Links for Eagle Days” page! Site: Eagles to the Nest Click “Lesson 1: Bald Eagles 101” and choose “Who Are They?” 1. How many species of eagles are found around the world? _________ 2. The term raptor comes from the Latin word for ________________, which stems from the term “rapture” meaning “____ _________ _____ _________ ________.” 3. Search the page to find the answers to each question. 1st Group - Sea and Fish Eagles (1) How many species belong to this group? ______ (2) Where do they live? _________________________________________________________ (3) What do they like to eat? ____________________________________________________ 2nd Group - Snake Eagles (1) How many species belong to this group? ______ (2) What do they eat? _________________________________________________________ (3) Where can you find these eagles? ___________________________________________ 3rd Group - Harpy Eagles (1) How many species belong to this group? ______ (2) Where do they live? _________________________________________________________ (3) What do they eat? __________________________________________________________ 4th Group - Booted Eagles (1) What do they eat? __________________________________________________________ (2) What one characteristic do all booted eagles have in common? _______________ ___________________________________________________________________________ Identify each eagle by its group using SF for Sea and Fish eagles, S for Snake eagles, H for Harpy eagles, and B for Booted eagles. _____ American Bald Eagle _____ Harpy Eagle _____ Golden Eagle _____ Bateleur _____ Crested Serpent Eagle _____ Steller’s Sea Eagle _____ Black Solitary Eagle _____ Ayres’ Hawk Eagle 4. Where are bald eagles found? ______________________________________________________ 5. Which is larger: a female or male bald eagle? ______________________________________ 6. -

Chromosome Painting in Three Species of Buteoninae: a Cytogenetic Signature Reinforces the Monophyly of South American Species

Chromosome Painting in Three Species of Buteoninae: A Cytogenetic Signature Reinforces the Monophyly of South American Species Edivaldo Herculano C. de Oliveira1,2,3*, Marcella Mergulha˜o Tagliarini4, Michelly S. dos Santos5, Patricia C. M. O’Brien3, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith3 1 Laborato´rio de Cultura de Tecidos e Citogene´tica, SAMAM, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Ananindeua, PA, Brazil, 2 Faculdade de Cieˆncias Exatas e Naturais, ICEN, Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil, 3 Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 4 Programa de Po´s Graduac¸a˜oem Neurocieˆncias e Biologia Celular, ICB, Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil, 5 PIBIC – Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil Abstract Buteoninae (Falconiformes, Accipitridae) consist of the widely distributed genus Buteo, and several closely related species in a group called ‘‘sub-buteonine hawks’’, such as Buteogallus, Parabuteo, Asturina, Leucopternis and Busarellus, with unsolved phylogenetic relationships. Diploid number ranges between 2n = 66 and 2n = 68. Only one species, L. albicollis had its karyotype analyzed by molecular cytogenetics. The aim of this study was to present chromosomal analysis of three species of Buteoninae: Rupornis magnirostris, Asturina nitida and Buteogallus meridionallis using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments with telomeric and rDNA probes, as well as whole chromosome probes derived from Gallus gallus and Leucopternis albicollis. The three species analyzed herein showed similar karyotypes, with 2n = 68. Telomeric probes showed some interstitial telomeric sequences, which could be resulted by fusion processes occurred in the chromosomal evolution of the group, including the one found in the tassociation GGA1p/GGA6. -

Field Identification of the Field Identification of the Field

TOPICS IN IDENTIFICATION he Solitary Eagle ( Harpyhaliaetus solitarius ) is a large raptor that is closely related and similar in adult and immature plum- Tages to the black-hawks in the genus Buteogallus (Lerner and Mindell 2005). It is a rare and very local resident in a variety of wet and dry forested hills and highlands from northern Argentina to northern Mexico (del Hoyo et al. 1994, Ferguson-Lees and Christie 2001). The species has been collected in Mexico not far from the Texas border (see Discussion, pp. 72 –73), so it is possible that it has occurred in the ABA Area. The handful of specimens and nest records of this eagle are from 700 to 2,000 meters above sea level (Brown and Amadon 1968). FFiieelldd IIddeennttiifificcaattiioonn ooff tthhee SSOOLLIITTTAAARRRYYY EEAAAGGGLLLEEE Nevertheless, sightings of this eagle are occasionally reported from lowland tropical rain forest, e.g., at Tikal, Guatemala (Beaver et al. 1991) and the Tuxtlas Mountains of south - William S. Clark ern Veracruz, Mexico (Winker et al. 1992). The species has been reported on some pro - 2301 South Whitehouse Circle fessional bird tours at such lowland sites as Palenque and the Usumicinta River in south - Harlingen, Texas 78550 ern Mexico. All of these accounts have relied on large size and gray coloration as the [email protected] field marks to distinguish the eagles from the much more abundant Common Black- Hawk ( Buteogallus anthracinus ) and Great Black-Hawk ( B. urubitinga ). H. Lee Jones Howell and Webb (1995) were skeptical and stated that most lowland records of the 4810 Park Newport, No. -

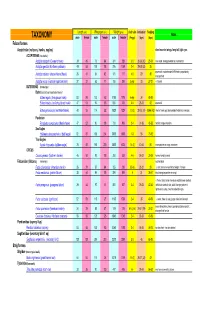

Avian Taxonomy

Length (cm) Wing span (cm) Weight (gms) cluch size incubation fledging Notes TAXONOMY male female male female male female (# eggs) (days) (days) Falconiformes Accipitridae (vultures, hawks, eagles) short rounded wings; long tail; light eyes ACCIPITRINAE (true hawks) Accipiter cooperii (Cooper's hawk) 39 45 73 84 341 528 3-5 30-36 (30) 25-34 crow sized; strongly banded tail; rounded tail Accipiter gentilis (Northern goshawk) 49 58 101 108 816 1059 2-4 28-38 (33) 35 square tail; most abundant NAM hawk; proportionaly 26 31 54 62 101 177 4-5 29 30 Accipiter striatus (sharp-shinned hawk) strongest foot Accipiter nisus (Eurasian sparrowhawk ) 37 37 62 77 150 290 5-Apr 33 27-31 Musket BUTEONINAE (broadwings) Buteo (buzzards or broad tailed hawks) Buteo regalis (ferruginous hawk) 53 59 132 143 1180 1578 6-Apr 34 45-50 Buteo lineatus (red-shouldered hawk) 47 53 96 105 550 700 3-4 28-33 42 square tail Buteo jamaicensis (red-tailed hawk) 48 55 114 122 1028 1224 1-3 (3) 28-35 (34) 42-46 (42) (Harlan' hawk spp); dark patagial featehres: immature; Parabuteo Parabuteo cuncincutus (Harris hawk) 47 52 90 108 710 890 2-4 31-36 45-50 reddish orange shoulders Sea Eagles Haliaeetus leucocephalus (bald eagle) 82 87 185 244 3000 6300 1-3 35 70-92 True Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (golden eagle) 78 82 185 220 3000 6125 1-4 (2) 40-45 50 white patches on wings: immature; CIRCUS Circus cyaneus (Northern harrier) 46 50 93 108 350 530 4-6 26-32 30-35 hovers; hunts by sound Falconidae (falcons) (longwings) notched beak Falco columbarius (American merlin) 26 29 57 64 -

Estimations Relative to Birds of Prey in Captivity in the United States of America

ESTIMATIONS RELATIVE TO BIRDS OF PREY IN CAPTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by Roger Thacker Department of Animal Laboratories The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210 Introduction. Counts relating to birds of prey in captivity have been accomplished in some European countries; how- ever, to the knowledge of this author no such information is available in the United States of America. The following paper consistsof data related to this subject collected during 1969-1970 from surveys carried out in many different direc- tions within this country. Methods. In an attempt to obtain as clear a picture as pos- sible, counts were divided into specific areas: Research, Zoo- logical, Falconry, and Pet Holders. It became obvious as the project advanced that in some casesthere was overlap from one area to another; an example of this being a falconer working with a bird both for falconry and research purposes. In some instances such as this, the author has used his own judgment in placing birds in specific categories; in other in- stances received information has been used for this purpose. It has also become clear during this project that a count of "pets" is very difficult to obtain. Lack of interest, non-coop- eration, or no available information from animal sales firms makes the task very difficult, as unfortunately, to obtain a clear dispersal picture it is from such sourcesthat informa- tion must be gleaned. However, data related to the importa- tion of birds' of prey as recorded by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife is included, and it is felt some observa- tions can be made from these figures. -

Timing and Abundance of Grey-Faced Buzzards Butastur Indicus and Other Raptors on Northbound Migration in Southern Thailand, Spring 2007–2008

FORKTAIL 25 (2009): 90–95 Timing and abundance of Grey-faced Buzzards Butastur indicus and other raptors on northbound migration in southern Thailand, spring 2007–2008 ROBERT DeCANDIDO and CHUKIAT NUALSRI We provide the first extensive migration data about northbound migrant raptors in Indochina. Daily counts were made at one site (Promsri Hill) in southern Thailand near the city of Chumphon, from late February through early April 2007–08. We identified 19 raptor species as migrants, and counted 43,451 individuals in 2007 (112.0 migrants/hr) and 55,088 in 2008 (160.6 migrants/hr), the highest number of species and seasonal totals for any spring raptor watch site in the region. In both years, large numbers of raptors were first seen beginning at 12h00, and more than 70% of the migration was observed between 14h00 and 17h00 with the onset of strong thermals and an onshore sea breeze from the nearby Gulf of Thailand. Two raptor species, Jerdon’s Baza Aviceda jerdoni and Crested Serpent Eagle Spilornis cheela, were recorded as northbound migrants for the first time in Asia. Four species composed more than 95% of the migration: Black Baza Aviceda leuphotes (mean 50.8 migrants/hr in 2007–08), Grey-faced Buzzard Butastur indicus (47.5/hr in 2007–08), Chinese Sparrowhawk Accipiter soloensis (22.3/hr in 2007–08), and Oriental Honey-buzzard Pernis ptilorhynchus (7.5/hr in 2007–08). Most (>95%) Black Bazas, Chinese Sparrowhawks and Grey-faced Buzzards were observed migrating in flocks. Grey-faced Buzzard flocks averaged 25–30 birds/ flock. Seasonally, our counts indicate that the peak of the Grey-faced Buzzard migration occurs in early to mid-March, while Black Baza and Chinese Sparrowhawk peak in late March through early April. -

SMCSP & SMCSN Wildlife List.Xlsx

Appendix C: Wildlife list for Six Mile Cypress Slough and Six Mile Cypress North Preserves Designated Status Scientific Name Common Name FWC FWS FNAI MAMMALS Family: Didelphidae (opossums) Didelphis virginiana Virginia opossum Family: Dasypodidae (armadillos) Dasypus novemcinctus nine-banded armadillo * Family: Sciuridae (squirrels and their allies) Sciurus carolinensis eastern gray squirrel Sciurus niger avicennia Big Cypress fox squirrel T G5T2/S2 Family: Muridae (mice and rats) Peromyscus gossypinus cotton mouse Oryzomys palustris marsh rice rat Sigmodon hispidus hispid cotton rat Family: Leporidae (rabbits and hares) Sylvilagus palustris marsh rabbit Sylvilagus floridanus eastern cottontail Family: Talpidae (moles) Scalopus aquaticus eastern mole Family: Felidae (cats) Puma concolor coryi Florida panther E E G5T1/S1 Lynx rufus bobcat Felis silvestris domestic cat * Family: Canidae (wolves and foxes) Urocyon cinereoargenteus common gray fox Family: Ursidae (bears) Ursus americanus floridanus Florida black bear T G5T2/S2 Family: Procyonidae (raccoons) Procyon lotor raccoon Family: Mephitidae (skunks) Spilogale putorius eastern spotted skunk Mephitis mephitis striped skunk Family: Mustelidae (weasels, otters and relatives) Lutra canadensis northern river otter Family: Suidae (old world swine) Sus scrofa feral hog * Family: Cervidae (deer) Odocoileus virginianus white-tailed deer BIRDS Family: Anatidae (swans, geese and ducks) Subfamily: Anatinae (dabbling ducks) Dendrocygna autumnalis black-bellied whistling duck Cairina moschata muscovy -

Super Cool Vet School - the Belize Zoo

Super Cool Vet School - The Belize Zoo Super Cool Vet School Apart from providing a happy home for the wildlife that comes our way, other important facets of zoology are also addressed at The Belize Zoo. For a week, a hands–on training course was held at the Zoo in collaboration with the Ross Veterinary School. Ross Vet School students examining 9 ft female croc, "Mrs. B." Nine students, along with two faculty members joined local veterinarians and animal management staff to undertake important medical procedures. The students were in high energy learning mode the entire week, and the zoo animals became patients for a bit, benefiting from this expert care and attention. What went on? The harpy eagles had their beaks trimmed (this makes eating an easier task, they appreciate that!), a 9 foot crocodile was examined thoroughly and given vitamins, blood was taken from the jabiru storks and scarlet macaws so that post-tests will reveal what sex these birds are, and jaguar CT was put into dreams–ville with appropriate drugs, so that a thorough check up could now be in his medical history. Other dynamic activities occurred, too. Jaguar field researcher Omar Figueroa gave a presentation about his important studies taking place in the central Jaguar Corridor. Primate researchers Kaylee and Patrick, from University of Calgary, told all about their exciting research involving both Howler and Spider monkeys in Runaway Creek Nature Reserve. Zoo Director Sharon Matola lectured on conservation and environmental awareness drawing attention to the good, the bad, and the ugly. Good: Harpy Eagle Restoration Program. -

Human-Wildlife Conflicts in the Southern Yungas

animals Article Human-Wildlife Conflicts in the Southern Yungas: What Role do Raptors Play for Local Settlers? Amira Salom 1,2,3,*, María Eugenia Suárez 4 , Cecilia Andrea Destefano 5, Joaquín Cereghetti 6, Félix Hernán Vargas 3 and Juan Manuel Grande 3,7 1 Laboratorio de Ecología y Conservación de Vida Silvestre, Centro Austral de Investigaciones Científicas (CADIC-CONICET), Bernardo Houssay 200, Ushuaia 9410, Argentina 2 Departamento de Ecología, Genética y Evolución, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Buenos Aires C1428EGA, Argentina 3 The Peregrine Fund, 5668 West Flying Hawk Lane, Boise, ID 83709, USA; [email protected] (F.H.V.); [email protected] (J.M.G.) 4 Grupo de Etnobiología, Departamento de Biodiversidad y Biología Experimental, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, e Instituto de Micología y Botánica (INMIBO), Universidad de Buenos Aires, CONICET-UBA, Intendente Güiraldes 2160, Buenos Aires C1428EGA, Argentina; [email protected] 5 Área de Agroecología, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Av. San Martín 4453, Buenos Aires C1417, Argentina; [email protected] 6 Las Jarillas 83, Santa Rosa 6300, Argentina; [email protected] 7 Colaboratorio de Biodiversidad, Ecología y Conservación (ColBEC), INCITAP (CONICET-UNLPam), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales (FCEyN), Universidad Nacional de La Pampa (UNLPam), Avda, Uruguay 151, Santa Rosa 6300, Argentina * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Human-Wildlife conflict (HWC) has become an important threat producing Citation: Salom, A.; Suárez, M.E.; biodiversity loss around the world. As conflictive situations highly depend on their unique socio- Destefano, C.A.; Cereghetti, J.; Vargas, ecological context, evaluation of the different aspects of the human dimension of conflicts is crucial to F.H.; Grande, J.M. -

Status of the Large Forest Eagles of Belize

Birds of Prey Bull. No. 3 (1986) Status of the large Forest Eagles of Belize Jack Clinton-Eitniear INTRODUCTION AND COUNTRY PROFILE Belize (formerly British Honduras) is located in northern Central America, bordered by Mexico on the north and Guatemala to the west and south. It is the second smallest (22,963 km2) country on the western hemisphere mainland. Including territorial waters in the Caribbean Seaj Belize's geographic co-ordinates are Ì5"53' to 18°30' N latitude and 87 15' to 89° 15' W longitude (Hartshorn et al., 1984). According to the Holdridge Life Zone system (Holdridge, 1947) most of Belize falls into the subtropical category. Tropical Moist and Tropical Wet zones do exist in the central and southern coastal areas. In total Belize has ove2r 15,812 km? of closed broadleaf forest (FAO 1978) of which 9,653 km is in permanent forest reserves or unreserved state land. Its 0.125 million inhabitants (Meyers 1980) are concentrated in a few major cities along its four major highways. Five species of eagles or hawk-eagles inhabit Belize with an additional species, Morphnus guianensis, possibly occurring within the country as its presence in nearby Guatemala has been documented (Ellis & Whaley, 1981). The following represents our current knowledge as to the status of Harpyhaliaetus solitarius, Harpia harpyja, Spizastur inelanoleucus, Spizaetus ornatus and Spizaetus tyrannus in BelTze. Black Solitary Eagle (Harpyhaliaetus solitarius) Inhabiting forested mountain slopes from south-eastern Sonora to Chiapas, Mexico, and throughout Central America to Venezuela and Peru (Peterson & Chalif 1973), the species is considered "little known" by Brown (1976) and "insufficiently known" by Meyburg (1986). -

Repeated Sequence Homogenization Between the Control and Pseudo

Repeated Sequence Homogenization Between the Control and Pseudo-Control Regions in the Mitochondrial Genomes of the Subfamily Aquilinae LUIS CADAH´IA1*, WILHELM PINSKER1, JUAN JOSE´ NEGRO2, 3 4 1 MIHAELA PAVLICEV , VICENTE URIOS , AND ELISABETH HARING 1Molecular Systematics, 1st Zoological Department, Museum of Natural History Vienna, Vienna, Austria 2Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Estacio´n Biolo´gica de Don˜ana, Sevilla, Spain 3Centre of Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES), Department of Biology, Faculty for Natural Sciences and Math, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway 4Estacio´n Biolo´gica Terra Natura (Fundacio´n Terra Natura—CIBIO), Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain ABSTRACT In birds, the noncoding control region (CR) and its flanking genes are the only parts of the mitochondrial (mt) genome that have been modified by intragenomic rearrangements. In raptors, two noncoding regions are present: the CR has shifted to a new position with respect to the ‘‘ancestral avian gene order,’’ whereas the pseudo-control region (CCR) is located at the original genomic position of the CR. As possible mechanisms for this rearrangement, duplication and transposition have been considered. During characterization of the mt gene order in Bonelli’s eagle Hieraaetus fasciatus, we detected intragenomic sequence similarity between the two regions supporting the duplication hypothesis. We performed intra- and intergenomic sequence comparisons in H. fasciatus and other falconiform species to trace the evolution of the noncoding mtDNA regions in Falconiformes. We identified sections displaying different levels of similarity between the CR and CCR. On the basis of phylogenetic analyses, we outline an evolutionary scenario of the underlying mutation events involving duplication and homogenization processes followed by sporadic deletions.