Iowa's Air Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

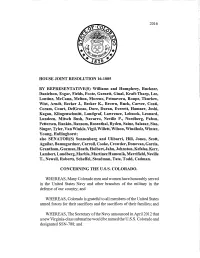

House Joint Resolution 16-1005 by Representative(S

2016 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 16-1005 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Williams and Humphrey, Buckner, Danielson, Esgar, Fields, Foote, Garnett, Ginal, Kraft-Tharp, Lee, Lontine, McCann, Melton, Moreno, Primavera, Roupe, Thurlow, Wist, Arndt, Becker J., Becker K., Brown, Buck, Carver, Conti, Coram, Court, DelGrosso, Dore, Duran, Everett, Hamner, Joshi, Kagan, Klingenschmitt, Landgraf, Lawrence, Lebsock, Leonard, Lundeen, Mitsch Bush, Navarro, Neville P., Nordberg, Pabon, Pettersen, Rankin,Ransom, Rosenthal, Ryden, Saine, Salazar, Sias, Singer, Tyler, VanWinkle, Vigil, Willett, Wilson~ Windholz, Winter, Young, Hullinghorst; also SENATOR(S) Sonnenberg and Ulibarri, Hill, Jones, Scott, Aguilar, Baumgardner,Carroll, Cooke, Crowder,Donovan, Garcia, Grantham, Guzman, Heath, Holbert,Jahn,Johnston, Kefalas, Kerr, Lambert,Lundberg, Marble, MartinezHumenik, Merrifield, Neville T., Newell, Roberts, Scheffel;Steadman, Tate, Todd, Cadman. CONCERNING THE V.S.S. COLORADO. WHEREAS, Many Colorado men and women have honorably served in the United States Navy and other branches of the military in the defense ofour country; and WHEREAS, Colorado is grateful to all members ofthe United States armed forces for their sacrifices and the sacrifices oftheir families; and WHEREAS, The Secretary ofthe Navy announced in April 2012 that a newVirginia-class submarine would be namedthe U.S.S. Colorado and designated SSN-788; and WHEREAS, The U.S.S. Colorado will stretch 377 feet and, in addition to its traditional attack submarine roles, will have accommodations for Navy SEALs and carry Tomahawk missiles with a striking distance of900 miles; and WHEREAS, Ithas been nearly two generations since a United States naval warship has borne the proud name ofthe great state ofColorado; and WHEREAS, This will be the fourth United States naval warship so christened, following the great traditions of the battleship U.S.S. -

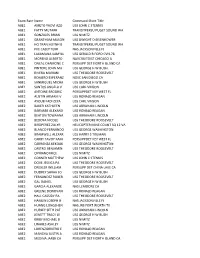

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

USN Ship Designations

USN Ship Designations By Guy Derdall and Tony DiGiulian Updated 17 September 2010 Nomenclature History Warships in the United States Navy were first designated and numbered in system originating in 1895. Under this system, ships were designated as "Battleship X", "Cruiser X", "Destroyer X", "Torpedo Boat X" and so forth where X was the series hull number as authorized by the US Congress. These designations were usually abbreviated as "B-1", "C-1", "D-1", "TB-1," etc. This system became cumbersome by 1920, as many new ship types had been developed during World War I that needed new categories assigned, especially in the Auxiliary ship area. On 17 July 1920, Acting Secretary of the Navy Robert E. Coontz approved a standardized system of alpha-numeric symbols to identify ship types such that all ships were now designated with a two letter code and a hull number, with the first letter being the ship type and the second letter being the sub-type. For example, the destroyer tender USS Melville, first commissioned as "Destroyer Tender No. 2" in 1915, was now re-designated as "AD-2" with the "A" standing for Auxiliary, the "D" for Destroyer (Tender) and the "2" meaning the second ship in that series. Ship types that did not have a subclassification simply repeated the first letter. So, Battleships became "BB-X" and Destroyers became "DD-X" with X being the same number as previously assigned. Ships that changed classifications were given new hull numbers within their new designation series. The designation "USS" standing for "United States Ship" was adopted in 1907. -

Us Navy Dreadnoughts 1914–45

US NAVY DREADNOUGHTS 1914–45 RYAN K. NOPPEN ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL WRIGHT © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com NEW VANGUARD 208 US NAVY DREADNOUGHTS 1914–45 RYAN K. NOPPEN © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 THE SOUTH CAROLINA CLASS 7 t South Carolina Class Specifications THE DELAWARE AND FLORIDA CLASSES 10 t Delaware Class Specifications t Florida Class Specifications WYOMING CLASS 15 t Wyoming Class Specifications NEW YORK CLASS 18 t New York Class Specifications US DREADNOUGHT BATTLESHIP OPERATIONS 1914–18 20 t The Veracruz Occupation t World War I INTERWAR SCRAPPING, DISARMAMENT AND MODERNIZATION 34 US DREADNOUGHT BATTLESHIP OPERATIONS 1939–45 35 t Neutrality Patrols t Actions in the European Theater t Actions in the Pacific Theater CONCLUSION 45 BIBLIOGRAPHY 46 INDEX 48 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com US NAVY DREADNOUGHTS 1914–45 INTRODUCTION The United States was the second of the great naval powers to embrace the concept of the all-big-gun dreadnought battleship in the early 20th century. The US Navy was seen as an upstart by much of the international community, after it experienced a rapid increase in strength in the wake of the Spanish- American War. American naval expansion paralleled that of another upstart naval power, Germany, whose navy also saw meteoric growth in this period. What is little known is that a tacit naval arms race developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries between these two powers, due primarily to soured foreign relations caused by a rivalry over colonial territory in the Pacific and an economic rivalry in Latin America. -

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc

Biography Denver General Subject Railroads States and Cities Misc. Visual Materials BIOGRAPHY A Abeyta family Abbott, Emma Abbott, Hellen Abbott, Stephen S. Abernathy, Ralph (Rev.) Abot, Bessie SEE: Oversize photographs Abreu, Charles Acheson, Dean Gooderham Acker, Henry L. Adair, Alexander Adami, Charles and family Adams, Alva (Gov.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) (Adams, Elizabeth Matty) Adams, Alva Blanchard Jr. Adams, Andy Adams, Charles Adams, Charles Partridge Adams, Frederick Atherton and family Adams, George H. Adams, James Capen (“Grizzly”) Adams, James H. and family Adams, John T. Adams, Johnnie Adams, Jose Pierre Adams, Louise T. Adams, Mary Adams, Matt Adams, Robert Perry Adams, Mrs. Roy (“Brownie”) Adams, W. H. SEE ALSO: Oversize photographs Adams, William Herbert and family Addington, March and family Adelman, Andrew Adler, Harry Adriance, Jacob (Rev. Dr.) and family Ady, George Affolter, Frederick SEE ALSO: oversize Aichelman, Frank and Agnew, Spiro T. family Aicher, Cornelius and family Aiken, John W. Aitken, Leonard L. Akeroyd, Richard G. Jr. Alberghetti, Carla Albert, John David (“Uncle Johnnie”) Albi, Charles and family Albi, Rudolph (Dr.) Alda, Frances Aldrich, Asa H. Alexander, D. M. Alexander, Sam (Manitoba Sam) Alexis, Alexandrovitch (Grand Duke of Russia) Alford, Nathaniel C. Alio, Giusseppi Allam, James M. Allegretto, Michael Allen, Alonzo Allen, Austin (Dr.) Allen, B. F. (Lt.) Allen, Charles B. Allen, Charles L. Allen, David Allen, George W. Allen, George W. Jr. Allen, Gracie Allen, Henry (Guide in Middle Park-Not the Henry Allen of Early Denver) Allen, John Thomas Sr. Allen, Jules Verne Allen, Orrin (Brick) Allen, Rex Allen, Viola Allen William T. -

Pa3529data.Pdf

{:, \ F f) Httt2~ PHILJt HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD ,,,.,_ 7 U.S.S. OLYMPIA HAER No. PA-428 Location: At the Independence Seaport Museum, Penn's Landing, 211 South Columbus Boulevard & Walnut Street on the Delaware River, in the City of Philadelphia, County of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Zone Easting Northing UTM Coordinates: 18 487292 4421286 Quad: Philadelphia, PA. - N.J. 1:24000 Dates of Construction: Authorized September 7, 1888, Keel laid June 17, 1891, Launched November 5, 1892, Commissioned February 5, 1895 Builder: Union Iron Works, San Francisco, California Official Number: C-6 (original designation) Cost: $1,796,000 Specifications: Protected cruiser, displacement 5870 tons, length 344 feet, beam 53 feet, draft 21.5 feet, maximum speed 21.686 knots, 6 boilers producing 17,313 horsepower. twin screws-triple expansion engines. Original Armament: 4 - 8 11 rifles 14 - 6 pounders 10 - 5" rifles 6 - 1 pounders 6 - torpedo tubes Complement: 34 officers; 440 enlisted men Present Owner: Independence Seaport Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Present Use: Decommissioned. National memorial and maritime museum. Significance: U.S.S. Olympia is a partially armored or protected cruiser which was constructed as part of a congressional program to build a new steel United States navy prior to the tum of the century. Her innovative design incorporated modern armament, high speed engines and armor shielding the magazines and propulsion machinery. She is the oldest extant steel hulled warship in the world. The U.S.S. Olympia was the flagship of Admiral George Dewey's victorious task force at the battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898. During the first two decades of the 19th century she protected American lives and interests in Panama, Dominican Republic, Murmansk (Russia), Croatia and Serbia. -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

Halyards-Fall-2016.Pdf

~ United States Navy ~ United States Marine Corps ~ United States Coast Guard ~ United States Flag Merchant Marine ~ Vol. X, No. 334 Colorado Springs Council Fall 2016 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~ HALYARDS ~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 2014 #1 and 2015 #2 NLUS Small Council Newsletter http://www.navyleague-coloradosprings.org/ COUNCIL CALENDAR Council Dinner & Annual Meeting – November 2 Sep 24 - Board Meeting, 0900, Mimi’s, N. Academy Location: PAFB Club Social hour: 5:30 pm. Dinner: 6:30 pm. Oct 8 - Board Meeting, 0900, Mimi’s, N. Academy Price: $25 Nov 2 – Council Dinner Meeting, 1730, PAFB Meal Options: London Broil, Chicken Cordon Bleu Nov 5 - Board Meeting, 0900, Mimi’s N. Academy Speaker: TBD Dec 3 - Board Meeting, 0900, Mimi’s, N. Academy Please RSVP by October 28 to Steve Bethke at [email protected] or (719) 359-3710. FROM THE PRESIDENT Anyone interested in Navy League, the sea services, or our speakers/topics is welcome at any of our I hope this finds everyone ready for fall. Below are a events. You don’t have to be a member of NLUS! couple quick points to emphasize as you get into this quarter’s Halyards. Board of Directors Elections – Nov 2 First, our website is constantly being updated with items The Nominating Committee (Dick, Deborah, Bunny) of interest. Please click on: http://www.navyleague- have developed the following slate of candidates for coloradosprings.org. A couple of “near term” election to the 2017 Board of Directors at our November opportunities to get together are the USNA-USAFA council Annual Meeting and dinner: Football Game on 1 October and the Navy Ball on 15 Elected Officials October. -

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No

All Guns Blazing! Newsletter of the Naval Wargames Society No. 282 – APRIL 2018 ‘The eyes of the world are now focused on the Falkland Islands. Others are watching anxiously to see whether brute force or the rule of law will triumph. Wherever naked aggression occurs it must be overcome. The cost now, however high, must be set against the cost we would one day have to pay if this principle went by default. That is why, through diplomatic, economic and, if necessary, through military means, we shall persevere until freedom and democracy are restored to the people of the Falkland Islands.’ – Margaret Thatcher, 14 April 1982 Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson chose St. David's Day to announce the name of one of the new Type 26 warships as HMS Cardiff. The third to be named in the City Class of eight brand new, cutting-edge, anti- submarine warfare frigates, HMS Cardiff will provide advanced protection for the likes of the UK’s nuclear deterrent and Queen Elizabeth Class aircraft carriers. It’s great to see the name HMS Cardiff returning to the Fleet as one of our new Type 26 Frigates, reflecting the Royal Navy’s long- standing bond with the city and the people of Wales. The name HMS Cardiff brings with it a proud history. A century ago the light cruiser HMS Cardiff famously led the German High Seas Fleet into internment at Scapa Flow at the end of the First World War. The last HMS Cardiff, a Type 42 destroyer, also distinguished herself on operations around the world, including the 1982 Falklands campaign, the 1991 Gulf War and service in the Adriatic during the 1999 crisis in Kosovo. -

Carrier Battles: Command Decision in Harm's Way Douglas Vaughn Smith

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Carrier Battles: Command Decision in Harm's Way Douglas Vaughn Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES CARRIER BATTLES: COMMAND DECISION IN HARM'S WAY By DOUGLAS VAUGHN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History, In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Douglas Vaughn Smith defended on 27 June 2005. _____________________________________ James Pickett Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ William J. Tatum Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member _____________________________________ Donald D. Horward Committee Member _____________________________________ James Sickinger Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This work is dedicated to Professor Timothy H. Jackson, sailor, scholar, mentor, friend and to Professor James Pickett Jones, from whom I have learned so much. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Professor Timothy H. Jackson, Director, College of Distance Education, U.S. Naval War College, for his faith in me and his continuing support, without which this dissertation would not have been possible. I also wish to thank Professor James Pickett Jones of the Florida State University History Department who has encouraged and mentored me for almost a decade. Professor of Strategy and Policy and my Deputy at the Naval War College Stanley D.M. Carpenter also deserves my most grateful acknowledgement for taking on the responsibilities of my job as well as his own for over a year in order to allow me to complete this project. -

USS Arizona Memorial

USS Arizona Memorial Administrative History Review Draft 1.0 September 15, 2004 Prepared for the National Park Service Prepared by Spencer Architects, Inc. 18109 University Avenue #101 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 [email protected] Table of Contents DRAFT 2.2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE TO THE REVIEW DRAFT (not completed for Draft 2.2) Scope of Work Research problems Recommendations for Completion INTRODUCTION (not completed for Draft 2.2) Purpose of Administrative History General Description of Process and Participants CONTEXT Era of the Battleship Design of Arizona Armament Armor Belt Machinery Crew Compliment Arizona’s Service Record Design of the Utah Pearl Harbor Attack Ward confrontation Torpedo trail picture in Harbor Attack on the Utah Attack on the Arizona Damage Assessment Pearl harbor Salvage Operations Arizona Salvage Operations Battery Arizona BUILDING A MEMORIAL Ideas about a Memorial Pacific War Memorial Commission Navy Ideas about a Memorial Congressional Legislation Fundraising Design of the Arizona Memorial Maintenance of the Memorial Structure BUILDING A PARK Construction of the Visitor Center Design of the Visitor Center Changes to Building Page 1 of 3 Printed 6/22/19 Table of Contents DRAFT 2.2 Elvis Fans Visitors MANAGEMENT ISSUE: RESOURCES Historic Resources Collections Objects Collection Documents Collection Oral History Collection Use of the Collection Collection Management Issues Planning Documents Natural Resources Federal Policies Entrance Fee Policy Budget Close down Boat Tours MANAGEMENT ISSUES: RESEARCH Mapping Surveys Record drawings Reconnaissance of Site Bifouling Study Cyclical monitoring program MANAGEMENT ISSUE: RELATIONSHIPS US Navy Boundary between sacred historic resource and secular harbor Ford Island Development Control of the Waters in Pearl Harbor The Arizona Memorial Museum Association Pearl Harbor Survivors Association Japanese Pearl Harbor Friendship Association Blind Vendors USS Arizona Memorial Fund Controversial Relationship Issues Japanese tourists. -

Remarks by USS Colorado Committee Chairman, John Mackin

Remarks by USS Colorado Committee Chairman, John Mackin Thank you, Madam Chairwoman, and Members of the Committee As a 26‐year, nuclear submarine officer and now, since retiring from the Navy, a 22‐year resident of Colorado, I am extremely excited and very proud to have a submarine named Colorado. It is indeed, a great honor to the state, and to all the citizens of Colorado, to have such a great ship with the name of our state, and it calls to mind the great traditions of the USS Colorado’s that have gone before. I will speak more to that in a moment. The christening and commissioning of a Naval vessel is an important event with traditions going back centuries. In recent years, especially with ships named after cities and states, it has become a cause of great celebration for the namesake constituencies. The Commissioning ceremony itself is a Navy ceremony which the federal government will pay. But there are several, traditional activities that surround that ceremony which celebrate this achievement, and honors the hard work of the crew, and those activities are the responsibility of the Commissioning Committee. It is our task to organize and fund these events. To that end, we have first sought to raise awareness within the state. Our initial effort was the conduct of a contest to design the ship’s crest. We had about 140 entries, mostly from Colorado, but from other states, and internationally, as well. After the ship informed me of the winning design to be used as their Crest, I noted winner had an address in New York.