Naming Laws Their Reinforcement of the Gender Binary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

(1999) the Bearer of a Family Name Is Not Necessarily an Authority on Its Origin

THE BEARER OF A FAMILY NAME IS NOT NECESSARILY AN AUTHORITY ON ITS ORIGIN, MEANING, ETIOLOGY, OR HISTORY (ON THE SEFARDIC FAMILY NAME ADATO ~ ADATTO) David L. Gold THE JEWISH FAMILY NAME FILE Resumen. Trabajo que estudia con propiedad el origen, significado, etiología e historia del apellido Adato o Adatto. Resumo. Traballo no que se analizan as orixes, o significado, a etioloxía e a historia do apelido Adato ou Adatto. Abstract. This article studies the origin, meaning, etiology and history of the sefardic family name Adato or Adatto. 1. INTRODUCTION For several years, I had correspondence with Albert Adatto, who was born in Istanbul, Turkey, and recently died in Seattle, Washington. Shortly before his death, he wrote me: Some spell our family name with one t and others with two. The enclosed photocopy from page 284 of Moïse Franco's Histoire des Israélites de l'Empire Ottoman (Paris, 1897) is the basic source. My discipline is history and I discount anything unless I am satisfied with the quality of my source material. Here is our family tradition regarding our name. Please note that I cannot footnote anything. When our family left Spain in 1492, they went to Turkey by way of Italy, where they took on the Italian name of Adatto with two ts. We became Italian by name because it was safe and it was a highly desirable Italian name. In Italian, the word adatto means 'suitable, adequate'. By tradition we are an adaptable Sefaradi family that made the transition from Spain to Turkey via Italy with the greatest of ease in Italian style. -

Name Change Checklist

Name Change Checklist Government Agencies Social Security Administration Department of Motor Vehicles - driver's license, car title and registration Voter Registration US Passport Post Office, if change of address Military or Veteran Records Public Assistance Naturalization Papers Any open court orders Work and Employment W-4 Form 401k Health Insurance Benefits (including Beneficiaries) Email ID Card Business Cards Name Plate Work website / website contact information Unions Professional Organizations Professional Licenses Personal website – if you have a resume based website Banks / Financial Institutions Checking accounts, checks, and bank cards Savings and money market accounts, CDs Credit Cards Assets such as property titles, deeds, trusts Debts such as mortgages and personal loans Debts such as auto or school loans Investment accounts, including IRAs, and 401ks Insurance Policies such as life, disability Home Homeowners or renters insurance Landlord Home owners association or management agency Property Tax department / Tax assessor Utilities o Electric o Gas o Water / sewer o Telephones (including cell and landline) o Internet o Cable Auto Insurance Medical Doctor Dentist Ob-Gyn Therapists Counselors Eye Doctor Pharmacy Veterinarian / Micro Chip Company Personal School / School Records / Alumni Associations Groups, Associations, Organizations Subscriptions Airline Miles Programs Loyalty Clubs Road Toll Accounts Your Voicemail Gym Membership Church / Religious Organizations Other Legal Documents Health proxy Power of Attorney Will Living Trusts Your Attorney Social Media Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Flickr Instagram Personal Blog or Website Email Accounts Brought to you by http://www.littlethingsfavors.com . -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

Gaelic Names of Plants

[DA 1] <eng> GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS [DA 2] “I study to bring forth some acceptable work: not striving to shew any rare invention that passeth a man’s capacity, but to utter and receive matter of some moment known and talked of long ago, yet over long hath been buried, and, as it seemed, lain dead, for any fruit it hath shewed in the memory of man.”—Churchward, 1588. [DA 3] GAELIC NAMES OE PLANTS (SCOTTISH AND IRISH) COLLECTED AND ARRANGED IN SCIENTIFIC ORDER, WITH NOTES ON THEIR ETYMOLOGY, THEIR USES, PLANT SUPERSTITIONS, ETC., AMONG THE CELTS, WITH COPIOUS GAELIC, ENGLISH, AND SCIENTIFIC INDICES BY JOHN CAMERON SUNDERLAND “WHAT’S IN A NAME? THAT WHICH WE CALL A ROSE BY ANY OTHER NAME WOULD SMELL AS SWEET.” —Shakespeare. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCLXXXIII All Rights reserved [DA 4] [Blank] [DA 5] TO J. BUCHANAN WHITE, M.D., F.L.S. WHOSE LIFE HAS BEEN DEVOTED TO NATURAL SCIENCE, AT WHOSE SUGGESTION THIS COLLECTION OF GAELIC NAMES OF PLANTS WAS UNDERTAKEN, This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. [DA 6] [Blank] [DA 7] PREFACE. THE Gaelic Names of Plants, reprinted from a series of articles in the ‘Scottish Naturalist,’ which have appeared during the last four years, are published at the request of many who wish to have them in a more convenient form. There might, perhaps, be grounds for hesitation in obtruding on the public a work of this description, which can only be of use to comparatively few; but the fact that no book exists containing a complete catalogue of Gaelic names of plants is at least some excuse for their publication in this separate form. -

PRELIMINARY STAFF REPORT To: City Planning Commission Prepared By: Nicolette Jones, Stosh Kozlowski, Laura Baños, and Derreck Deason Date: February 16, 2015

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Consideration: Request by City Council Motion M-15-444 for the City Planning Commission to conduct a study and public hearing to amend its Administrative Rules, Policies, & Procedures relative to the creation of an honorary street name change process. Background: To date, the City of New Orleans does not have a policy related to an honorary street dedication program. Currently, the City’s street naming policy, which is documented in the City Planning Commission’s Administrative Rules, Policies, and Procedures, only delineates the procedure for street name changes. An honorary street dedication program, which many other jurisdictions across the country have implemented, allows cities the opportunity to commemorate individuals and groups who have made significant contributions to the community, but without causing any disruption of the existing street grid associated with a modification to the Official Map as would a permanent street name change. According to best practices, honorary street signage is typically a secondary sign that is installed above or below an existing street name sign. The City Council has granted honorary street dedications in the recent past, though without a formalized policy to guide the process. Following the recent approval of street name changes in the spring of 2015, the New Orleans City Council requested that the City Planning Commission review the City’s street renaming rules and explore opportunities to create an honorary street dedication program. Recommendation: In order to promote clear wayfinding, efficient emergency response and service delivery, as well as accurate address keeping, the staff advises against frequent changes to the City’s Official Map. -

Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Office of the Professions Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services www.op.nysed.gov DO NOT USE THIS FORM IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY. IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY, YOU MUST SUBMIT A CONTACT US FORM ON THE OFFICE OF THE PROFESSIONS' WEBSITE AT https://eservices.nysed.gov/professions/contact-us/#/ Instructions: Use this form to report a change in your name. Read these instructions carefully and complete all applicable sections of this form. Be sure to print clearly in ink. You must include acceptable supporting documentation. Acceptable supporting documentation includes: A photocopy of a court, marriage certificate, or divorce papers authorizing your name change and a photocopy of a photo ID in your new name. Or Two (2) of the following sets of supporting documents: ● A letter from the Social Security Administration indicating both your old and new names. ● Copies of both old and new driver's licenses. ● Copies of both old and new New York State non-driver photo ID cards. ● Copies of both old and new Social Security Cards. ● Copies of both old and new passports. ● Copies of both old and new U.S. Military photo ID cards. Other forms of identification may be acceptable as supporting documentation. Please contact the Records and Archives Unit by calling 518-474-3817 Extension 380 or by emailing [email protected] before submitting. Currently registered licensed professionals will be sent a new registration certificate. Also, if you would like to replace your existing license parchment with one in your new name, check the appropriate box in Section II and enclose your original parchment (your original parchment will be letter sized, 8.5 x 11 inches, and will not have your address on it). -

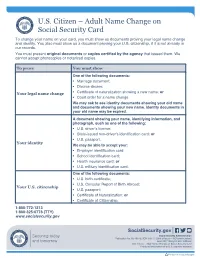

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Name Choice and the Assimilation of Immigrants in the United States, 1900-1930∗

Please Call Me John: Name Choice and the Assimilation of Immigrants in the United States, 1900-1930∗ Pedro Carneiro University College London, Institute for Fiscal Studies and Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice Sokbae Lee Seoul National University, Institute for Fiscal Studies and Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice Hugo Reis Bank of Portugal and Cat´olicaLisbon School of Business and Economics 11 February 2016 Abstract The vast majority of immigrants to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century adopted first names that were common among natives. The rate of adoption of an American name increases with time in the US, although most immigrants adopt an American name within the first year of arrival. Choice of an American first name was associated with a more successful assimilation, as measured by job occupation scores, marriage to a US native and take-up of US citizenship. We examine economic determi- nants of name choice, by studying the relationship between changes in the proportion of immigrants with an American first name and changes in the concentration of immi- grants as well as changes in local labor market conditions, across different census years. We find that high concentrations of immigrants of a given nationality in a particular location discouraged members of that nationality from taking American names. Poor local labor market conditions for immigrants (and good local labor market conditions for natives) led to more frequent name changes among immigrants. Key words: Americanization, culture, first name, identity, immigration JEL Classification Codes: J15, N32 ∗We would like to thank Christian Dustmann and Imran Rasul for their helpful comments, and Lucena Vieira for very competent research assistance. -

Names and “Doing Gender”: How Forenames and Surnames

Sex Roles DOI 10.1007/s11199-017-0805-4 FEMINIST FORUM REVIEW ARTICLE Names and BDoing Gender^: How Forenames and Surnames Contribute to Gender Identities, Difference, and Inequalities Jane Pilcher1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Names, as proper nouns, are clearly important for Nonetheless, practices of personal naming in these countries the identification of individuals in everyday life. In the present are patterned and structured: first, as a consequence of repli- article, I argue that forenames and surnames need also to be cation of usage of the names of individuals and recurring recognized as Bdoing^ words, important in the categorization demands for the authentication of individual identity over of sex at birth and in the ongoing management of gender time; second, by cultural traditions and conventions (including conduct appropriate to sex category. Using evidence on per- those patrilineal and patriarchal in origin) whereby personal sonal naming practices in the United States and United names are used to mark individual and social identities (Finch Kingdom, I examine what happens at crisis points of sexed 2008). Despite their fundamental and ubiquitous importance and gendered naming in the life course (for example, at the for each individual in a multitude of contexts, scholars are birth of babies, at marriage, and during gender-identity transi- only just beginning to give personal names and naming prac- tions). I show how forenames and surnames help in the em- tices Bthe theoretical and analytical scrutiny^ they deserve bodied doing of gender and, likewise, that bodies are key to (Palsson 2014,p.618). -

How to Host a Geography Quiz Night

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EDUCATION Geography Awareness Week How to Host a Geography Quiz Night Quiz or Trivia nights have been a pastime for people all over the world and been used as a fun fundraising tool for many groups. These can be at home, in a bar or restaurant, at a student union, lounge, church hall… really anywhere! Celebrating Geography Awareness Week can be really fun, but also stressful if you are unsure how to start. Use this guide to plan a quiz night to spread awareness where you are. 1. Establish a planning team: Seek support for the event from your principal/ adviser/ other key leaders. Form a team with volunteers or other interested organizations. Clearly define and divide roles and responsibilities among a few team members, and meet regularly for event planning. Consider the following team member roles: • Event Leader: Oversees events activities and timeline; organizes communication among team members; coordinates volunteers to help before, during and after the event. Will be the venue liaison and may need to be the mediator should play get out of hand. • Host: Should be well-spoken, personable, enjoys public speaking, can get a crowd excited and having a good time but will also be organized and able to ensure that everyone is being fair and friendly. • Promotions Coordinator: Places Geography Awareness Week posters in and around schools and throughout communities; coordinates invitations; connects with event partners and sponsors; contacts local and national TV, radio stations, and newspapers. 2. Plan your event: Allow about two months or more to plan the event. Consult with school administrators or other appropriate officials when selecting a time and place for your event. -

Unto Shauna Laurel, Evan Wreath, and Margaret Pelican and Those of the College of Arms Who Find Themselves in Receipt of This

Unto Shauna Laurel, Evan Wreath, and Margaret Pelican and those of the College of Arms who find themselves in receipt of this letter, greetings from Rowen Blue Tyger on behalf of Mistress Avelina Keyes, Brigantia Principal Herald of the East, on this feastday of Erconwald, Bishop and confessor, A.S. XXXVIII, also reckoned 30 April 2004 in the Common Era. This letter would not have been accomplished without the great help of Istvan Eastern Crown and Kat'ryna Diadem; my thanks to them both. It is the desire of the East that the following items be considered and registered by the College - 40 new primary names, 2 new change primary names, 1 new order name, 1 new household name, 41 new devices, 1 new change of device, and 10 new badges - for a total of 96 items. A cheque for these items, totaling $384, shall be sent separately. Additionally, there is 1 resub primary name and 2 resub devices. Unless otherwise mentioned, the submitter will accept all changes. I remain in your service, Lord Rowen Cloteworthy, Blue Tyger Herald mka Rowen Stuffer 2124 Harbour Dr., Palmyra, NJ 08065-1104 (856) 829-8709, [email protected] 1) Agnes Edith Godolphin (f) - new primary name One could make the argument that 'Edith' could be a surname. Reaney & Wilson, page 151 under "Edith", No major changes. The submitter would like her name to indicates that Edith became a surname, though the latest be changed to be authentic for 'late 16th century England'. form cited is 'John Idyth' dated 1327. She would like to keep the middle name 'Edith' if the use of middle names by women can be documented to the late 2) Ailionora inghean 16th century in England, but is willing to drop it if Ronain - new device - Argent, otherwise.