Eleven Fossils in Search of a Provincial Or Territorial Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Neoceratopsian Dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia And

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01222-7 OPEN A neoceratopsian dinosaur from the early Cretaceous of Mongolia and the early evolution of ceratopsia ✉ Congyu Yu 1 , Albert Prieto-Marquez2, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig 3,4, Zorigt Badamkhatan4,5 & Mark Norell1 1234567890():,; Ceratopsia is a diverse dinosaur clade from the Middle Jurassic to Late Cretaceous with early diversification in East Asia. However, the phylogeny of basal ceratopsians remains unclear. Here we report a new basal neoceratopsian dinosaur Beg tse based on a partial skull from Baruunbayan, Ömnögovi aimag, Mongolia. Beg is diagnosed by a unique combination of primitive and derived characters including a primitively deep premaxilla with four pre- maxillary teeth, a trapezoidal antorbital fossa with a poorly delineated anterior margin, very short dentary with an expanded and shallow groove on lateral surface, the derived presence of a robust jugal having a foramen on its anteromedial surface, and five equally spaced tubercles on the lateral ridge of the surangular. This is to our knowledge the earliest known occurrence of basal neoceratopsian in Mongolia, where this group was previously only known from Late Cretaceous strata. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that it is sister to all other neoceratopsian dinosaurs. 1 Division of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York 10024, USA. 2 Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, ICTA-ICP, Edifici Z, c/de les Columnes s/n Campus de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA. 4 Institute of Paleontology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, ✉ Ulaanbaatar 15160, Mongolia. -

Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza's Ethics

Midwest Studies in Philosophy, XXVI (2002) Eternity and Immortality in Spinoza’s Ethics STEVEN NADLER I Descartes famously prided himself on the felicitous consequences of his philoso- phy for religion. In particular, he believed that by so separating the mind from the corruptible body, his radical substance dualism offered the best possible defense of and explanation for the immortality of the soul. “Our natural knowledge tells us that the mind is distinct from the body, and that it is a substance...And this entitles us to conclude that the mind, insofar as it can be known by natural phi- losophy, is immortal.”1 Though he cannot with certainty rule out the possibility that God has miraculously endowed the soul with “such a nature that its duration will come to an end simultaneously with the end of the body,” nonetheless, because the soul (unlike the human body, which is merely a collection of material parts) is a substance in its own right, and is not subject to the kind of decomposition to which the body is subject, it is by its nature immortal. When the body dies, the soul—which was only temporarily united with it—is to enjoy a separate existence. By contrast, Spinoza’s views on the immortality of the soul—like his views on many issues—are, at least in the eyes of most readers, notoriously difficult to fathom. One prominent scholar, in what seems to be a cry of frustration after having wrestled with the relevant propositions in Part Five of Ethics,claims that this part of the work is an “unmitigated and seemingly unmotivated disaster.. -

Therapeutic Targeting of Replicative Immortality

Seminars in Cancer Biology 35 (2015) S104–S128 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seminars in Cancer Biology jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/semcancer Review Therapeutic targeting of replicative immortality a,∗ b c d e Paul Yaswen , Karen L. MacKenzie , W. Nicol Keith , Patricia Hentosh , Francis Rodier , f g h i c Jiyue Zhu , Gary L. Firestone , Ander Matheu , Amancio Carnero , Alan Bilsland , j k,1 k,1 l,1 Tabetha Sundin , Kanya Honoki , Hiromasa Fujii , Alexandros G. Georgakilas , m,1 n,o,1 p,1 q,1 Amedeo Amedei , Amr Amin , Bill Helferich , Chandra S. Boosani , r,1 s,1 t,1 u,1 Gunjan Guha , Maria Rosa Ciriolo , Sophie Chen , Sulma I. Mohammed , v,1 r,1 w,1 m,1 Asfar S. Azmi , Dipita Bhakta , Dorota Halicka , Elena Niccolai , s,1 n,o,1 x,1 p,1 Katia Aquilano , S. Salman Ashraf , Somaira Nowsheen , Xujuan Yang a Life Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, Berkeley, CA, United States b Children’s Cancer Institute Australia, Kensington, New South Wales, Australia c University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom d Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, United States e Universit´e de Montr´eal, Montr´eal, QC, Canada f Washington State University College of Pharmacy, Pullman, WA, United States g University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States h Biodonostia Institute, Gipuzkoa, Spain i Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla, HUVR, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Universdad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain j Sentara Healthcare, Norfolk, VA, United States k Nara Medical University, Kashihara, -

Offer Your Guests a Visually Stunning and Interactive Experience They Won’T Find Anywhere Else World of Animals

Creative Arts & Attractions Offer Your Guests a Visually Stunning and Interactive Experience They Won’t Find Anywhere Else World of Animals Entertain guests with giant illuminated, eye-catching displays of animals from around the world. Animal displays are made in the ancient Eastern tradition of lantern-making with 3-D metal frames, fiberglass, and acrylic materials. Unique and captivating displays will provide families and friends with a lifetime of memories. Animatronic Dinosaurs Fascinate patrons with an impressive visual spectacle in our exhibitions. Featured with lifelike appearances, vivid movements and roaring sounds. From the very small to the gigantic dinosaurs, we have them all. Everything needed for a realistic and immersive experience for your patrons. Providing interactive options for your event including riding dinosaurs and dinosaur inflatable slides. Enhancing your merchandise stores with dinosaur balloons and toys. Animatronic Dinosaur Options Abelisaurus Maiasaura Acrocanthosaurus Megalosaurus Agilisaurus Olorotitan arharensis Albertosaurus Ornithomimus Allosaurus Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Ankylosaurus Oviraptor philoceratops Apatosaurus Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis Archaeopteryx Parasaurolophus Baryonyx Plateosaurus Brachiosaurus Protoceratops andrewsi Carcharodontosaurus Pterosauria Carnotaurus Pteranodon longiceps Ceratosaurus Raptorex Coelophysis Rugops Compsognathus Spinosaurus Deinonychus Staurikosaurus pricei Dilophosaurus Stegoceras Diplodocus Stegosaurus Edmontosaurus Styracosaurus Eoraptor Lunensis Suchomimus -

Reptile Family Tree

Reptile Family Tree - Peters 2015 Distribution of Scales, Scutes, Hair and Feathers Fish scales 100 Ichthyostega Eldeceeon 1990.7.1 Pederpes 91 Eldeceeon holotype Gephyrostegus watsoni Eryops 67 Solenodonsaurus 87 Proterogyrinus 85 100 Chroniosaurus Eoherpeton 94 72 Chroniosaurus PIN3585/124 98 Seymouria Chroniosuchus Kotlassia 58 94 Westlothiana Casineria Utegenia 84 Brouffia 95 78 Amphibamus 71 93 77 Coelostegus Cacops Paleothyris Adelospondylus 91 78 82 99 Hylonomus 100 Brachydectes Protorothyris MCZ1532 Eocaecilia 95 91 Protorothyris CM 8617 77 95 Doleserpeton 98 Gerobatrachus Protorothyris MCZ 2149 Rana 86 52 Microbrachis 92 Elliotsmithia Pantylus 93 Apsisaurus 83 92 Anthracodromeus 84 85 Aerosaurus 95 85 Utaherpeton 82 Varanodon 95 Tuditanus 91 98 61 90 Eoserpeton Varanops Diplocaulus Varanosaurus FMNH PR 1760 88 100 Sauropleura Varanosaurus BSPHM 1901 XV20 78 Ptyonius 98 89 Archaeothyris Scincosaurus 77 84 Ophiacodon 95 Micraroter 79 98 Batropetes Rhynchonkos Cutleria 59 Nikkasaurus 95 54 Biarmosuchus Silvanerpeton 72 Titanophoneus Gephyrostegeus bohemicus 96 Procynosuchus 68 100 Megazostrodon Mammal 88 Homo sapiens 100 66 Stenocybus hair 91 94 IVPP V18117 69 Galechirus 69 97 62 Suminia Niaftasuchus 65 Microurania 98 Urumqia 91 Bruktererpeton 65 IVPP V 18120 85 Venjukovia 98 100 Thuringothyris MNG 7729 Thuringothyris MNG 10183 100 Eodicynodon Dicynodon 91 Cephalerpeton 54 Reiszorhinus Haptodus 62 Concordia KUVP 8702a 95 59 Ianthasaurus 87 87 Concordia KUVP 96/95 85 Edaphosaurus Romeria primus 87 Glaucosaurus Romeria texana Secodontosaurus -

Atlantic Geoscience Society Abstracts 1995 Colloquium

A t l a n t ic G eo l o g y 39 ATLANTIC GEOSCIENCE SOCIETY ABSTRACTS 1995 COLLOQUIUM AND ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING ANTIGONISH, NOVA SCOTIA The 1995 Colloquium of the Atlantic Geoscience Society was held in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, on February 3 to 4, 1995. On behalf of the Society, we thank Alan Anderson, Mike Melchin, Brendan Murphy, and all others involved in the organization of this excellent meeting. In the following pages we publish the abstracts of talks and poster sessions given at the Colloquium which included special sessions on "The Geological Evolution of the Magdalen Basin: ANatmap Project" and "Energy and Environmental Research in the Atlantic Provinces", as well as contri butions of a more general aspect. The Editors Atlantic Geology 31, 39-65 (1995) 0843-5561/95/010039-27S5.05/0 40 A b st r a c t s A study of carbonate rocks from the late Visean to Namurian Mabou Group, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia T.L. Allen Department o f Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3J5, Canada The Mabou Group, attaining a maximum thickness of7620 stituents of the lower Mabou Group. The types of carbonate m, lies conformably above the marine Windsor Group and rocks present include laminated lime boundstones (stromato unconformably below the fluviatile Cumberland Group. It com lites), floatstones, and grainstones. The stromatolites occur pre prises a lower grey lacustrine facies and an upper red fluviatile dominantly as planar laminated stratiform types and as later facies. The grey lacustrine facies consists predominantly of grey ally linked hemispheroids, some having a third order crenate siltstones and shales with interbedded sandstones, gypsum, and microstructure. -

A Passion for Palaeontology September 22, 2012-March 17, 2013

BACK COVER PAGE COVER PAGE Bearing Witness Inside the ROM Governors A dark chapter in ROM NEWSLETTER OF THE Cambodia’s history ROM GOVERNORS The Institute for Contemporary FALL/WINTER 2 012 Summer at the ROM has been a whirlwind of activity. Culture (ICC) presents Observance Exciting new initiatives such as Friday Night Live and our and Memorial: Photographs from family weekend programming have been extremely popular S-21, Cambodia, featuring over 100 and we have seen many new visitors and partners come photographs developed from original through our doors. Also hugely successful has been our negatives abandoned by the Khmer Special thanks to Susan Crocker and INSIDER groundbreaking exhibition Ultimate Dinosaurs: Giants from Rouge in January 1979, at the S-21 secret John Hunkin, Ron Graham, the Gondwana, which pioneers the use of Augmented Reality prison in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Honourable William C. Graham and and includes the largest dinosaur ever mounted in Canada. Curated by Photo Archive Group, and Cathy Graham, Deanna Horton, Dr. Carla Shapiro from the Munk School Richard W. Ivey, and Sarah and Tom This month, it is a great pleasure to welcome Robert Pierce of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, Milroy for their generous support of this as the new chairman of the Board of Governors. As a this exhibition calls attention to the exhibition. For information on how you long-time volunteer, Board member for more than 12 years, atrocities in Cambodia in the 1970s can support Observance and Memorial and supporter of the ROM, Rob has served in a leadership or to make a donation to the ICC, BIG and human rights issues. -

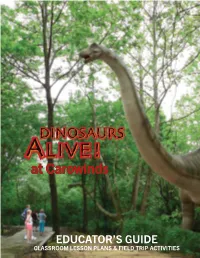

At Carowinds

at Carowinds EDUCATOR’S GUIDE CLASSROOM LESSON PLANS & FIELD TRIP ACTIVITIES Table of Contents at Carowinds Introduction The Field Trip ................................... 2 The Educator’s Guide ....................... 3 Field Trip Activity .................................. 4 Lesson Plans Lesson 1: Form and Function ........... 6 Lesson 2: Dinosaur Detectives ....... 10 Lesson 3: Mesozoic Math .............. 14 Lesson 4: Fossil Stories.................. 22 Games & Puzzles Crossword Puzzles ......................... 29 Logic Puzzles ................................. 32 Word Searches ............................... 37 Answer Keys ...................................... 39 Additional Resources © 2012 Dinosaurs Unearthed Recommended Reading ................. 44 All rights reserved. Except for educational fair use, no portion of this guide may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any Dinosaur Data ................................ 45 means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other without Discovering Dinosaurs .................... 52 explicit prior permission from Dinosaurs Unearthed. Multiple copies may only be made by or for the teacher for class use. Glossary .............................................. 54 Content co-created by TurnKey Education, Inc. and Dinosaurs Unearthed, 2012 Standards www.turnkeyeducation.net www.dinosaursunearthed.com Curriculum Standards .................... 59 Introduction The Field Trip From the time of the first exhibition unveiled in 1854 at the Crystal -

Meet the Gilded Lady 2 Mummies Now Open

Member Magazine Spring 2017 Vol. 42 No. 2 Mummies meet the gilded lady 2 mummies now open Seeing Inside Today, computerized inside of mummies, revealing CT scans of the Gilded Lady tomography (CT) scanning details about the person’s reveal that she was probably offers researchers glimpses age, appearance, and health. in her forties. They also suggest of mummified individuals “Scans like these are noninvasive, that she may have suffered like never before. By combining they’re repeatable, and they from tuberculosis, a common thousands of cross-sectioned can be done without damaging disease at the time. x-ray images, CT scans let the history that we’re trying researchers examine the to understand,” Thomas says. Mummy #30007, known as the Gilded Lady, is one of the most beautifully preserved mummies from The Field Museum’s collection, and one of 19 now on view in the special exhibition Mummies. For decades, keeping mummies like this one well preserved also meant severely limiting the ability of researchers to study them. The result is that little was known about the Gilded Lady beyond what could be gleaned from the mummy’s exterior, with its intricate linen bindings, gilded headdress, and painted facial features. Exterior details do offer some clues. The mummy dates from 30 BC–AD 395, a period when Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire. While the practice of mummification endured in Egypt, it was being transformed by Roman influences. Before the Roman era, for example, mummies had been placed in wooden coffins, while the Gilded Lady is preserved in only linen wrappings and cartonnage, a papier mâché-like material. -

HOVASAURUS BOULEI, an AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN from the UPPER PERMIAN of MADAGASCAR by P.J

99 Palaeont. afr., 24 (1981) HOVASAURUS BOULEI, AN AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF MADAGASCAR by P.J. Currie Provincial Museum ofAlberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T5N OM6, Canada ABSTRACT HovasauTUs is the most specialized of four known genera of tangasaurid eosuchians, and is the most common vertebrate recovered from the Lower Sakamena Formation (Upper Per mian, Dzulfia n Standard Stage) of Madagascar. The tail is more than double the snout-vent length, and would have been used as a powerful swimming appendage. Ribs are pachyostotic in large animals. The pectoral girdle is low, but massively developed ventrally. The front limb would have been used for swimming and for direction control when swimming. Copious amounts of pebbles were swallowed for ballast. The hind limbs would have been efficient for terrestrial locomotion at maturity. The presence of long growth series for Ho vasaurus and the more terrestrial tan~saurid ThadeosauTUs presents a unique opportunity to study differences in growth strategies in two closely related Permian genera. At birth, the limbs were relatively much shorter in Ho vasaurus, but because of differences in growth rates, the limbs of Thadeosau rus are relatively shorter at maturity. It is suggested that immature specimens of Ho vasauTUs spent most of their time in the water, whereas adults spent more time on land for mating, lay ing eggs and/or range dispersal. Specilizations in the vertebrae and carpus indicate close re lationship between Youngina and the tangasaurids, but eliminate tangasaurids from consider ation as ancestors of other aquatic eosuchians, archosaurs or sauropterygians. CONTENTS Page ABREVIATIONS . ..... ... ......... .......... ... ......... ..... ... ..... .. .... 101 INTRODUCTION . -

Place Names Describing Fossils in Oral Traditions

Place names describing fossils in oral traditions ADRIENNE MAYOR Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Folk explanations of notable geological features, including fossils, are found around the world. Observations of fossil exposures (bones, footprints, etc.) led to place names for rivers, mountains, valleys, mounds, caves, springs, tracks, and other geological and palaeonto- logical sites. Some names describe prehistoric remains and/or refer to traditional interpretations of fossils. This paper presents case studies of fossil-related place names in ancient and modern Europe and China, and Native American examples in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Evidence for the earliest known fossil-related place names comes from ancient Greco-Roman and Chinese literature. The earliest documented fossil-related place name in the New World was preserved in a written text by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. In many instances, fossil geonames are purely descriptive; in others, however, the mythology about a specific fossil locality survives along with the name; in still other cases the geomythology is suggested by recorded traditions about similar palaeontological phenomena. The antiquity and continuity of some fossil-related place names shows that people had observed and speculated about miner- alized traces of extinct life forms long before modern scientific investigations. Traditional place names can reveal heretofore unknown geomyths as well as new geologically-important sites. Traditional folk names for geological features in the Named fossil sites in classical antiquity landscape commonly refer to mythological or and modern Greece legendary stories that accounted for them (Vitaliano 1973). Landmarks notable for conspicuous fossils Evidence for the practice of naming specific fossil have been named descriptively or mythologically locales can be found in classical antiquity. -

The Cambrian Explosion: a Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals

The Cambrian Explosion A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Very suddenly, and at about the same horizon the world over, life showed up in the rocks with a bang. For most of Earth’s early history, there simply was no fossil record. Only recently have we come to discover otherwise: Life is virtually as old as the planet itself, and even the most ancient sedimentary rocks have yielded fossilized remains of primitive forms of life. NILES ELDREDGE, LIFE PULSE, EPISODES FROM THE STORY OF THE FOSSIL RECORD The Cambrian Explosion: A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Our home planet coalesced into a sphere about four-and-a-half-billion years ago, acquired water and carbon about four billion years ago, and less than a billion years later, according to microscopic fossils, organic cells began to show up in that inert matter. Single-celled life had begun. Single cells dominated life on the planet for billions of years before multicellular animals appeared. Fossils from 635,000 million years ago reveal fats that today are only produced by sponges. These biomarkers may be the earliest evidence of multi-cellular animals. Soon after we can see the shadowy impressions of more complex fans and jellies and things with no names that show that animal life was in an experimental phase (called the Ediacran period). Then suddenly, in the relatively short span of about twenty million years (given the usual pace of geologic time), life exploded in a radiation of abundance and diversity that contained the body plans of almost all the animals we know today.