Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spike: the Devil You Know Free

FREE SPIKE: THE DEVIL YOU KNOW PDF Franco Urru,Chris Cross,Bill Williams | 104 pages | 04 Jan 2011 | Idea & Design Works | 9781600107641 | English | San Diego, United States Spike: The Devil You Know - Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel Wiki Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to Spike: The Devil You Know. Want Spike: The Devil You Know Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Spike by Bill Williams. Chris Cross. While out and about drinking, naturally Spike gets in trouble over a girl of course and finds himself in the middle of a conspiracy that involves Hellmouths, blood factories, and demons. Just another day in Los Angeles, really. But when devil Eddie Hope gets involved, they might just kill each other before getting to the bad guys! Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Other Editions 3. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Spikeplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. The mini series sees a new character Eddie Hope stumble into Buffyverse alumni, Spike! I enjoyed their conversations but the general story was sort of Then again, that is the Buffyverse way of handling things! Jan 30, Sesana rated it it was ok Shelves: comicsfantasy. Well, that was pointless. The story is dull enough that I doubt the writer was interested in it. -

“The Wounded Angel Considers the Uses of So-Called Secular Literature to Convey Illuminations of Mystery, the Unsayable, the Hidden Otherness, the Holy One

“The Wounded Angel considers the uses of so-called secular literature to convey illuminations of mystery, the unsayable, the hidden otherness, the Holy One. Saint Ignatius urged us to find God in all things, and Paul Lakeland demonstrates how that’s theologically possible in fictions whose authors had no spiritual or religious intentions. A fine and much-needed reflection.” — Ron Hansen Santa Clara University “Renowned ecclesiologist Paul Lakeland explores in depth one of his earliest but perduring interests: the impact of reading serious modern fiction. He convincingly argues for an inner link between faith and religious imagination. Drawing on a copious cross section of thoughtful novels (not all of them ‘edifying’), he reasons that the joy of reading is more than entertainment but rather potentially salvific transformation of our capacity to love and be loved. Art may accomplish what religion does not always achieve. The numerous titles discussed here belong on one’s must-read list!” — Michael A. Fahey, SJ Fairfield University “Paul Lakeland claims that ‘the work of the creative artist is always somehow bumping against the transcendent.’ What a lovely thought and what a perfect summary of the subtle and significant argument made in The Wounded Angel. Gracefully moving between theology and literature, religious content and narrative form, Lakeland reminds us both of how imaginative faith is and of how imbued with mystery and grace literature is. Lakeland’s range of interests—Coleridge and Louise Penny, Marilynne Robinson and Shusaku Endo—is wide, and his ability to trace connections between these texts and relate them to large-scale theological questions is impressive. -

Angel Sanctuary, a Continuation…

Angel Sanctuary, A Continuation… Written by Minako Takahashi Angel Sanctuary, a series about the end of the world by Yuki Kaori, has entered the Setsuna final chapter. It is appropriately titled "Heaven" in the recent issue of Hana to Yume. However, what makes Angel Sanctuary unique from other end-of-the-world genre stories is that it does not have a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. It also displays a variety of worldviews with a distinct and unique cast of characters that, for fans of Yuki Kaori, are quintessential Yuki Kaori characters. With the beginning of the new chapter, many questions and motives from the earlier chapters are answered, but many more new ones arise as readers take the plunge and speculate on the series and its end. In the "Hades" chapter, Setsuna goes to the Underworld to bring back Sara's soul, much like the way Orpheus went into Hades to seek the soul of his love, Eurydice. Although things seem to end much like that ancient tale at the end of the chapter, the readers are not left without hope for a resolution. While back in Heaven, Rociel returns and thereby begins the political struggle between himself and the regime of Sevothtarte and Metatron that replaced Rociel while he was sealed beneath the earth. However the focus of the story shifts from the main characters to two side characters, Katou and Tiara. Katou was a dropout at Setsuna's school who was killed by Setsuna when he was possessed by Rociel. He is sent to kill Setsuna in order for him to go to Heaven. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Founded 1860 Lutheran Church Missouri Synod Worship in The

Founded 1860 Lutheran Church Missouri Synod Worship in the Sanctuary Sunday May 23rd Pastor Rev. Mark Moldenhauer (979) 551-2293 PastorMark @Bethlehem WmPenn.org Secretary Mrs. Amy Schroeder (979) 836-7303 Office @Bethlehem WmPenn.org Organist Ann Sommer AV Tech Ian Schroeder The Day of Pentecost May 23, 2021 Divine Service: Setting One with Communion Pre-Service Music Ringing of the Church Bell At Bethlehem Lutheran Church we teach and confess that Holy Communion consists of four different visible elements: the bread, the wine, the body, and the blood. When the Word of God is added to the bread and wine it is the body and blood of Jesus Christ, 1 Cor. 11: 23-26. There are many different beliefs concerning Holy Communion so on the basis of 1 Cor. 11: 27-29 we request that you speak with the Pastor or one of the Elders before receiving Holy Communion. PROCESSIONAL HYMN We Praise You and Acknowledge You, O God LSB 941 Text: © 1999 Stephen P. Starke, admin. Concordia Publishing House. Used by permission: LSB Hymn License no. 110005013 Tune: Public domain CONFESSION AND ABSOLUTION LSB 151 P In the name of the Father and of the T Son and of the Holy Spirit. C Amen. P If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. C But if we confess our sins, God, who is faithful and just, will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. P Let us then confess our sins to God our Father. C Most merciful God, we confess that we are by nature sinful and unclean. -

Sfx: a Gun Cocks. Wes Fires.)

Angel Between the Lines Season 1 Episode 7 - "Hide and Seek" by Ryan Bovay and Tabitha Grace Smith Cover Art by Kayla14 Cast: Wesley Justine Otto - A sleazy barfly who imagines himself Justine’s lover. Carl (Bartender) – Sympathetic to Justine, but still serves what is ordered. Julia – Justine’s twin sister. Having overcome the abuse their mother inflicted upon her by training as a Potential Slayer in London, Julia returns to L.A. to reconnect with Justine and help her do the same. Julia is intelligent, articulate, and acutely aware of the emotional obstacles she’s battled through. Diana - Early-mid 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Hawkins - Late 30's, mercenary working for Wesley Mason - Lilah’s legal assistant and is in his early 30’s. He’s sharp, an egotist and an expert self-preservationist, which is what has allowed him to survive at Wolfram and Hart thus far. Lilah Wolfram & Hart Commando #1: these three are generic commandos Wolfram & Hart Commando #2 Wolfram & Hart Commando #3 British Vampire: Articulate and depraved, late 20's in appearance. Relishes rare kills like a chef does rare ingredients. Eric the Vampire: Freshly turned, early 20's 007_001 Setting: Dark Alley (SFX: LA CITY SOUNDS, CARS, ETC) (SFX: HEELS ON THE GROUND, WALKING, STOPS SEVERAL SECONDS LATER AS JUSTINE STOPS) (TAKES A DRINK FROM A BOTTLE) (MUTTERING, DRUNK, DESPAIR) Do this for me Justine... you have to do this for me. JUSTINE: (DRINKS FROM BOTTLE) You have to kill me so you’re alone again... always alone. (CREEPY MAN WHO JUST SHOWS UP CREEPILY) Not always alone Justine. -

Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series Editor: Lyn White

BOOK PUBLISHERS Teachers’ Notes Angel: Through My Eyes - Natural Disaster Zones by Zoe Daniel Series editor: Lyn White ISBN 9781760113773 Recommended for ages 11-14 yrs These notes may be reproduced free of charge for use and study within schools but they may not be reproduced (either in whole or in part) and offered for commercial sale. Introduction ............................................ 2 Links to the curriculum ............................. 5 Background information for teachers ....... 12 Before reading activities ......................... 14 During reading activities ......................... 16 After-reading activities ........................... 20 Enrichment activities ............................. 28 Further reading ..................................... 30 Resources ............................................ 32 About the writer and series editor ............ 32 Blackline masters .................................. 33 Allen & Unwin would like to thank Heather Zubek and Sunniva Midtskogen for their assistance in creating these teachers notes. 83 Alexander Street PO Box 8500 Crows Nest, Sydney St Leonards NSW 2065 NSW 1590 ph: (61 2) 8425 0100 [email protected] Allen & Unwin PTY LTD Australia Australia fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 www.allenandunwin.com ABN 79 003 994 278 INTRODUCTION Angel is the fourth book in the Through My Eyes – Natural Disaster Zones series. This contemporary realistic fiction series aims to pay tribute to the inspiring courage and resilience of children, who are often the most vulnerable in post-disaster periods. Four inspirational stories give insight into environment, culture and identity through one child’s eyes. www.throughmyeyesbooks.com.au Advisory Note There are children in our schools for whom the themes and events depicted in Angel will be all too real. Though students may not be at risk of experiencing an immediate disaster, its long-term effects may still be traumatic. -

U.S. V. Angel Rivero

Jul 7, 2017 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT cYffiKVS DIST°CTE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA I s.D. OF FLA -MJ^Ml 17-204J5.GR-COOKE/GOODMAN 18 U.S.C. § 1960(a) 18 U.S.C. § 2 18 U.S.C. § 982 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, vs. ANGEL RIVERO, Defendant. / INFORMATION The Acting United States Attorney charges that: 1. Pursuant to Title 18, United States Code, Section 1960(b)(2), the term "money transmitting" included transferring funds on behalf of the public by any and all means, including but not limited to, transfers within this country or to locations abroad by wire, check, draft, facsimile, or courier. 2. At all times relevant to this Information, money transmitters operating in the State of Florida were required to register under Florida law. 3. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO register with the State of Florida or obtain a license from the State of Florida to operate a money transmitting business. 4. At no time relevant to this Information did defendant ANGEL RIVERO comply with money transmitting business registration requirements pursuant to Title 31, United States Code, Section 5330. Case l:17-cr-20475-MGC Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 07/07/2017 Page 2 of 6 UNLICENSED MONEY TRANSMITTER (18 U.S.C. § 1960) From on or about May 22, 2014, through on or about March 11, 2015, in Miami-Dade County, in the Southern District of Florida, and elsewhere, the defendant, ANGEL RIVERO, did knowingly conduct, control, manage, supervise, direct, and own all or part of an unlicensed money transmitting business, as that -

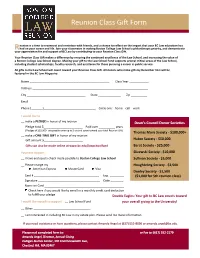

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

2019 11 Newsletter Copy

MEDICINE HAT & DISTRICT LIVE MUSIC CLUB Live Newsletter NOV 2019 Music Club Editor: Betty Bischke [email protected] In Memoriam Albert William “Billy” Jones, beloved husband of the late Nina Mabel Jones, passed away peacefully on Thursday October 24, 2019 at the age of 88 years. He leaves to cherish his memory his children Carolynn and her daughter Lindsay, and David (Tammy) and their children Alexander and Connor. He was predeceased by his wife of 53 years Nina, his parents Doris and Henry and his sister Margaret. It is difficult to capture the depth and richness of life in so brief a span. Billy’s life was dedicated to his family, friends, music and to God. Originally born and raised in Toronto, ON, Billy early on became dedicated to music. Although he also explored talents in Tool and Die Making, electronics and other passions, music and the steel guitar were the consistent theme of his professional life and for most that knew him, they were an inseparable combination. It was in Toronto that he met his wife Nina and together spent years touring the continent driven by the country and western sound that dominated his musical focus. His talent for the steel guitar was legendary. He played with some of the greats: Stompin’ Tom Connors, Hank Williams Sr., King Ganam and Tommy Hunter (to name but a few). Billy and Nina went on to pursue a family, with their children Carolynn and David, eventually moving out to Medicine Hat, AB, where they enjoyed the remainder of their lives building new relationships with great friends discovered there. -

Intuitive Angel Card Reader Course Guidebook

Intuitive Angel Card Reader Course Guidebook Melanie Beckler www.Ask-Angels.com CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Invocation 3 Our Private Facebook Group 5 Questions for Your Angel Card Readings 9 Angel Card Reading Spreads 16 30 Day Challenge 18 Certification Introduction Every aspect of this Intuitive Angel Card Readings Course has been guided by the angels. By going through the course in it’s entirely, listening to each of the videos in order, and then looping back to re-listen and dive in deeper to certain sessions, psychic tools, and experiences, the angels will help you to lift into a higher vibrational state of love and light. The intention, and energy present in this course will help you to clearly connect with an- gelic guidance, heighten your intuition, and more fully align with your highest authentic truth and light. Connecting with angels is fun, healing, powerful, enlightening and rewarding on so many levels. Be willing to set aside your preconceived notions of what connecting with the angels should be like, or might be like so you can tune into the light, power and possibilities that are present in your authentic connection with the angels that is! I’m honored that you’ve decided to join me in completing this course. If at any time you need assistance accessing the course components, or with anything at all, email us at [email protected]. With love, light and gratitude, Invocation Calling upon your angels before each and every Intuitive Angel Card Reading is an essential part of your set-up process that you will learn more about in the video course.