Zim Feasibility-Of-Adoldsd Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres

Midlands Province Mobile Voter Registration Centres Chirumhanzu District Team 1 Ward Centre Dates 18 Mwire primary school 10/06/13-11/06/13 18 Tokwe 4 clinic 12/06/13-13/06/13 18 Chingegomo primary school 14/06/13-15/06/13 16 Chishuku Seondary school 16/06/13-18/06/13 9 Upfumba Secondary school 19/06/13-21/06/13 3 Mutya primary school 22/06/13-24/06/13 2 Gonawapotera secondary school 25/06/13-27/06/13 20 Wildegroove primary school 28/06/13-29/06/13 15 Kushinga primary school 30/06/13-02/07/13 12 Huchu compound 03/07/13-04/-07/13 12 Central estates HQ 5/7/13 20 Mtao/Fair Field compound 6/7/13 12 Chiudza homestead 07/07/13-08/06/13 14 Njerere primary school 9/7/13 Team 2 Ward Centre Dates 22 Hillview Secondary school 10/07/13-12/07/13 17 Lalapanzi Secondary school 13/07/13-15/07/13 16 Makuti homestead 16/06/13-17/06/13 1 Mapiravana Secondary school 18/06/13-19/06/13 9 Siyahukwe Secondary school 20/06/13-23/06/13 4 Chizvinire primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 21 Mukomberana Seconadry school 26/06/13-29/06/13 20 Union primary school 30/06/13-01/07/13 15 Nyikavanhu primary school 02/07/13-03/07/13 19 Musens primary school 04/07/13-06/07/13 16 Utah primary school 07/7/13-09/07/13 Team 3 Ward Centre Dates 11 Faerdan primary school 10/07/13-11/07/13 11 Chamakanda Secondary school 12/07/13-14/07/13 11 Chamakanda primary school 15/07/13-16/07/13 5 Chizhou Secondary school 17/06/13-16/06/13 3 Chilimanzi primary school 21/06/13-23/06/13 25 Maponda primary school 24/06/13-25/06/13 6 Holy Cross seconadry school 26/06/13-28/06/13 20 New England Secondary -

(Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020

Statutory Instrument 55 ofS.I. 2020. 55 of 2020 Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) [CAP. 23:02 Order, 2020 (No. 20) Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) “THIRTEENTH SCHEDULE Order, 2020 (No. 20) CUSTOMS DRY PORTS IT is hereby notifi ed that the Minister of Finance and Economic (a) Masvingo; Development has, in terms of sections 14 and 236 of the Customs (b) Bulawayo; and Excise Act [Chapter 23:02], made the following notice:— (c) Makuti; and 1. This notice may be cited as the Customs and Excise (Ports (d) Mutare. of Entry and Routes) (Amendment) Order, 2020 (No. 20). 2. Part I (Ports of Entry) of the Customs and Excise (Ports of Entry and Routes) Order, 2002, published in Statutory Instrument 14 of 2002, hereinafter called the Order, is amended as follows— (a) by the insertion of a new section 9A after section 9 to read as follows: “Customs dry ports 9A. (1) Customs dry ports are appointed at the places indicated in the Thirteenth Schedule for the collection of revenue, the report and clearance of goods imported or exported and matters incidental thereto and the general administration of the provisions of the Act. (2) The customs dry ports set up in terms of subsection (1) are also appointed as places where the Commissioner may establish bonded warehouses for the housing of uncleared goods. The bonded warehouses may be operated by persons authorised by the Commissioner in terms of the Act, and may store and also sell the bonded goods to the general public subject to the purchasers of the said goods paying the duty due and payable on the goods. -

Factors Associated with Exclusive Breastfeeding in Accra, Ghana

UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Faculty of Community and Health Sciences FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH EXCLUSIVE BREASTFEEDING IN KWEKWE DISTRICT, ZIMBABWE THEMBA NDUNA, MSc, BSc, Dip A Mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Public Health, in the Faculty of Community and Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape December 2011 Supervisor: Dr. Brian van Wyk i DECLARATION I, the undersigned declare that this thesis has been composed by myself and that the research it describes has been done by me. The thesis has not been accepted in any previous application for a degree elsewhere. All quotations have been distinguished by quotation marks and the sources of information clearly acknowledged by means of references. Signed: Name: Themba Nduna Date: 31 / 12 /2011 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere thanks and gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Brian van Wyk, for his advice and guidance throughout the course of this study. Conducting research using a qualitative approach was such a challenge and pain-staking endeavour, particularly as a new experience quite unfamiliar for me. Dr van Wyk continued not to only challenge me but also to encourage, motivate and inspire me through positive feedback and that coupled with relevant guidance I got this far. I thank you, Brian. This study would not have been successful without invaluable support from the administration staff of the School of Public Health. If I do not mention the two beloved people, my wife Ruth and my one and only daughter Simphiwethina, my acknowledgement would be incomplete and short of sincerity. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Turmoil in Zimbabwe's Mining Sector

All That Glitters is Not Gold: Turmoil in Zimbabwe’s Mining Sector Africa Report N°294 | 24 November 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Makings of an Unstable System ................................................................................ 5 A. Pitfalls of a Single Gold Buyer ................................................................................... 5 B. Gold and Zimbabwe’s Patronage Economy ............................................................... 7 C. A Compromised Legal and Justice System ................................................................ 10 III. The Bitter Fruits of Instability .......................................................................................... 14 A. A Spike in Machete Gang Violence ............................................................................ 14 B. Mounting Pressure on the Mnangagwa Government ............................................... 15 C. A Large-scale Police Operation .................................................................................. 16 IV. Three Mines, Three Stories of Violence .......................................................................... -

Midlands Province

School Province District School Name School Address Level Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BARU KUSHINGA PRIMARY BARU KUSHINGA VILLAGE 48 CENTAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK MUSENA RESETTLEMENT AREA VILLAGE 1 MUSENA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu BUSH PARK 2 VILLAGE 5 WARD 19 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CAMBRAI ST MATHIAS LALAPANZI TOWNSHIP CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKA NDARUZA VILLAGE HEAD CHAKA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAKASTEAD FENALI VILLAGE NYOMBI SIDING Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT SCHEME MVUMA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAPWANYA HWATA-HOLYCROSS ROAD RUDUMA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIHOSHO MATARITANO VILLAGE HEADMAN DEBWE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHILIMANZI NYONGA VILLAGE CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIMBINDI CHIMBINDI VILLAGE WARD 5 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINGEGOMO WARD 18 TOKWE 4 VILLAGE 16 CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHINYUNI CHINYUNI WARD 7 CHUKUCHA VILLAGE Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIRAYA (WYLDERGROOVE) MVUMA HARARE ROAD WASR 20 VILLAGE 1 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU CHISHUKU VILAGE 3 CHIEF CHIRUMANZU Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHITENDERANO TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT AREA WARD 11 Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWESHE PONDIWA VILLAGE MAPIRAVANA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT AREA Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA NO 2 VILLAGE 66 CHIWODZA CENTRAL ESTATES Primary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZVINIRE CHIZVINIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE WARD 4 Primary Midlands -

The Undersigned Authenticate That the the Midlands State University for Assessing Zimbabwean Local Housing: Challenges and Oppor

APPROVAL FORM The undersigned authenticate that they have supervised and recommended to the Midlands State University for acceptance the dissertation entitled: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Of Kwekwe City Council. Submitted by :Christiner Mjanga Reg. No. R134524H in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Sciences Honours Degree in Local Governance Studies. ..................................................... ...................................................... SUPERVISIOR DATE .................................................... ........................................................ CHAIRPERSON DATE i FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE RELEASE FORM Name of Student: Christiner Mjanga Registration Number: R134524H Dissertation title: Assessing Zimbabwean Local Authorities` capacity to deliver affordable housing- Challenges and Opportunities: Case of Kwekwe City Council. Degree to which Dissertation was presented: Bsc Honours in Local governance studies Year this degree granted: 2016 Permission is hereby granted to the Midlands State University library to produce single copies of this dissertation and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research only. The author reserves other publication rights and neither the dissertation nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author`s written permission. Signed ...................................................... -

VII. the Unity Government Response

HUMAN RIGHTS THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections WATCH The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0220 The Elephant in the Room Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security Sector Ahead of Elections List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... ii I. Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

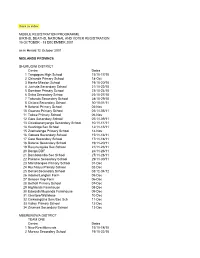

Back to Index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME

Back to index MOBILE REGISTRATION PROGRAMME BIRTHS, DEATHS, NATIONAL AND VOTER REGISTRATION 15 OCTOBER - 13 DECEMBER 2001 as in Herald 12 October 2001 MIDLANDS PROVINCE SHURUGWI DISTRICT Centre Dates 1 Tongogara High School 15/10-17/10 2 Chironde Primary School 18-Oct 3 Hanke Mission School 19/10-20/10 4 Juchuta Secondary School 21/10-22/10 5 Dombwe Primary School 23/10-24/10 6 Svika Secondary Schoo 25/10-27/10 7 Takunda Secondary School 28/10-29/10 8 Chitora Secondary School 30/10-01/11 9 Batanai Primary School 02-Nov 10 Gwanza Primary School 03/11-05/11 11 Tokwe Primary School 06-Nov 12 Gare Secondary School 07/11-09/11 13 Chivakanenyanga Secondary School 10/11-11/11 14 Kushinga Sec School 12/11-13/11 15 Zvamatenga Primary School 14-Nov 16 Gamwa Secondary School 15/11-16/11 17 Gato Secondary School 17/11-18/11 18 Batanai Secondary School 19/11-20/11 19 Rusununguko Sec School 21/11-23/11 20 Donga DDF 24/11-26/11 21 Dombotombo Sec School 27/11-28/11 22 Pakame Secondary School 29/11-30/11 23 Marishongwe Primary School 01-Dec 24 Ruchanyu Primary School 02-Dec 25 Dorset Secondary School 03/12-04/12 26 Adams/Longton Farm 05-Dec 27 Beacon Kop Farm 06-Dec 28 Bethall Primary School 07-Dec 29 Highlands Farmhouse 08-Dec 30 Edwards/Muponda Farmhouse 09-Dec 31 Glentore/Wallclose 10-Dec 32 Chikwingizha Sem/Sec Sch 11-Dec 33 Valley Primary School 12-Dec 34 Zvumwa Secondary School 13-Dec MBERENGWA DISTRICT TEAM ONE Centre Dates 1 New Resettlements 15/10-18/10 2 Murezu Secondary School 19/10-22/10 3 Chizungu Secondary School 23/10-26/10 4 Matobo Secondary -

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary

School Level Province District School Name School Address Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHAMAKANDA LYNWOOD CENTER TAKAWIRA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHENGWENA RAMBANAPASI VILLAGE, CHIEF HAMA CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHISHUKU VILLAGE 2A CHISHUKU RESETLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIVONA DENHERE VILLAGE WARD 3 MHENDE CMZ Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIWODZA VILLAGE 38 CHIWODZA RESETTLEMENT MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu CHIZHOU WARD 5 MUZEZA VILLAGE, HEADMAN BANGURE , CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DANNY DANNY SEC Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu DRIEFONTEIN DRIEFONTEIN MISSION FARM Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu GONAWAPOTERA CHAKA BUSINESS CENTRE MVUMA MASVINGO ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HILLVIEW HILLVIEW VILLAGE1, LALAPANZI Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu HOLY CROSS HOLY CROSS MISSION WARD 6 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LALAPANZI 42KM ALONG GWERU-MVUMA ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA LEOPOLD TAKAWIRA 2KM ALONG CENTRAL ESTATES ROAD Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MAPIRAVANA MAPIRAVANA VILLAGE WARD 1CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUKOMBERANWA MUWANI VILLAGE HEADMAN MANHOVO Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSENA VILLAGE 8 MUSENA RESETTLEMENT Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUSHANDIRAPAMWE RUDHUMA VILLAGE WARD 25 CHIRUMANZU Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu MUTENDERENDE DZORO VILLAGE CHIEF HAMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu NEW ENGLAND LOVEDALE FARMSUB-DIVISION 2 MVUMA Secondary Midlands Chirumanzu ORTON'S DRIFT ORTON'S DRIFT FARM Secondary Midlands -

Midlands North Inspection Stations

MIDLANDS NORTH INSPECTION STATIONS GOKWE CENTRAL 1 BHEJANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHEVECHEVE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3 CHIDAMOYO PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIDOMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 CHITAPO BUSINESS CENTRE 6 GANYUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 GWANYIKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 GWENUNGU PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GWENYA PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 JAHANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 KASIKANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 KRIMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 MALIYAMI PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 MAPU PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 MTANKI PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 MUTANGE C.B. PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 MWEMBESI PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 NDABAMBI PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 NHONGO PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 SATENGWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 SENGWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 SIMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 ST. CUTHBERTS MASORO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 TONGWE SECONDARY SCHOOL 25 CHIZIYA COMMUNITY HALL 26 GABABE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 RAJI MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT 28 GWEHAVA PRIMARY SCHOOL GOKWE EAST 1 BATSIRAI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2 CHAMINUKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 3 CHINYENYETU PRIMARY SCHOOL 4 CHIODZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 COPPER QUEEN BUSINESS CENTRE 6 DENDA PRIMARY SCHOOL 7 DEWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 DINDIMUTIWI PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 GANDAVACHE PRIMARY SCHOOL 10 GOREDEMA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 GWEBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 HWADZE PRIMARY SCHOOL 13 KAHOBO PRIMARY SCHOOL 14 KAMWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 15 KAMWAMBE PRIMARY SCHOOL 16 KASONDE PRIMARY SCHOOL 17 KUEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 18 KWAEDZA PRIMARY SCHOOL 19 MADZIDRIRE PRIMARY SCHOOL 20 MASOSONI PRIMARY SCHOOL 21 MHUMHA PRIMARY SCHOOL 22 MSADZI PRIMARY SCHOOL 23 MUDONDO PRIMARY SCHOOL 24 MUPAWA PRIMARY SCHOOL 25 MUSOROWENZOU PRIMARY SCHOOL 26 MUTEHWE PRIMARY SCHOOL 27 MUTUKANYI PRIMARY SCHOOL 28 NORAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 29 NYAMAZENGWE PRIMARY -

OTHER ISSUES ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & Mps, JUNE 2000

Zimbabwe, Country Information Page 1 of 95 ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE PAST & PRESENT ANNEX D: FULL ELECTION RESULTS JUNE 2000 (hard copy only) ANNEX E: MDC CANDIDATES & MPs, JUNE 2000 & MDC LEADERSHIP & SHADOW CABINET ANNEX F: MDC POLICIES, PARTY SYMBOLS AND SLOGANS ANNEX G: CABINET LIST, AUGUST 2002 ANNEX H: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This country report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The country report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The country report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the country report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom.