2009 National Values Education Conference Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching Students to Text!

8068528 The Lexile Framework® for Reading Matching students to text! Matching students to texts at appropriate levels helps to increase their confidence, competence, and control over the reading process. The Lexile Framework is a reliable and tested tool designed to bridge two critical aspects of student reading achievement — levelling text difficulty and assessing the reading skills of each student. SCHOOL YEAR LEXILE LEVEL BENCHMARK LITERATURE SAMPLE TEXT PASSAGES The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1530 Strange Objects Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray 1270 When the Minister for National Heritage engaged me to translate the manuscript which Strange Objects by Gary Crew 1200 appears for the first time in this paper today, I expected the task would be purely academic. 1200L– War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy 1200 Naturally, I was honoured to be undertaking the translation of such an important work, and eager to provide as accurate an interpretation of the text as I could, but nothing could Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 1200 12 1700L have prepared me for the human element, the personality of the writer. Fired Up by Sarah Ell 1180 The Wind in the Willows Animal Farm by George Orwell 1170 ‘Look here,’ he went on, ‘this is what occurs to me. There’s a sort of dell down there in front The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells 1170 of us, where the ground seems all hilly and humpy and hummocky. We’ll make our way Diary Z by Stephanie McCarthy 1140 down into that, and try and find some sort of shelter, a cave or hole with a dry floor to it, out of the snow and the wind, and there we’ll have a good rest before we try again, for we’re The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame 1140 11 1100L both of us pretty dead beat. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

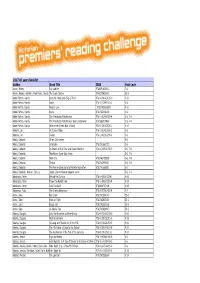

FINAL 2017 All Years Booklist.Xlsx

2017 All years Booklist Author Book Title ISBN Year Level Aaron, Moses Lily and Me 9780091830311 7-8 Aaron, Moses (reteller); Mackintosh, David (ill.)The Duck Catcher 9780733412882 EC-2 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Does My Head Look Big in This? 978-0-330-42185-0 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Jodie 978-1-74299-010-1 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Noah's Law : 9781742624280 9-10 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Rania 9781742990188 5-6 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker 978-1-86291-920-4 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa The Friendship Matchmaker Goes Undercover 9781862919488 5-6, 7-8 Abdel-Fattah, Randa Where the Streets Had a Name 978-0-330-42526-1 9-10 Abdulla, Ian As I Grew Older 978-1-86291-183-3 5-6 Abdulla, Ian Tucker 978-1-86291-206-9 5-6 Abela, Deborah Ghost Club series 5-6 Abela, Deborah Grimsdon 9781741663723 5-6 Abela, Deborah In Search of the Time and Space Machine 978-1-74051-765-2 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Max Remy Super Spy series 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah New City 9781742758558 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah Teresa 9781742990941 5-6, 7-8 Abela, Deborah The Remarkable Secret of Aurelie Bonhoffen 9781741660951 5-6 Abela, Deborah; Warren, Johnny Jasper Zammit Soccer Legend series 5-6, 7-8 Abrahams, Peter Behind the Curtain 978-1-4063-0029-1 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Down the Rabbit Hole 978-1-4063-0028-4 9-10 Abrahams, Peter Into The Dark 9780060737108 9-10 Abramson, Ruth The Cresta Adventure 978-0-87306-493-4 3-4 Acton, Sara Ben Duck 9781741699142 EC-2 Acton, Sara Hold on Tight 9781742833491 EC-2 Acton, Sara Poppy Cat 9781743620168 EC-2 Acton, Sara As Big As You 9781743629697 -

Walter Mcvitty Books Publisher's Archive

A Guide to the Walter McVitty Books Publisher’s Archive The Lu Rees Archives The Library University of Canberra October 2002 Scope and Content Note • Papers • 1984 – 1997 • 25 boxes • Series 6 (Publishers) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) • Series 9, (Finance and Sales) is restricted for 15 years. (2003-2018) These papers were donated to the Lu Rees Archives in 2000 under the Cultural Gifts Program. The papers are a complete record of the publishing company ‘Walter McVitty Books’, from its inception in 1985 until it’s sale in 1997. They are unique because this company was the only publisher to exclusively publish Australian children’s books. The papers include correspondence, reviews, artwork, contracts, awards, financial statements, manuscripts, book dummies and publicity materials. The major correspondents are the authors and illustrators, especially Colin Thiele and John Marsden; other publishers, and book clubs and associations. This finding aid was prepared by Management of Archives students Kerri Kemister, Wendy-Anne Quarmby and Lisa Roulstone, under the supervision of Professor Belle Alderman. Walter McVitty Biographical Note Prepared by: Cathie Bartley, Karen Ottoway and Amanda Rebbeck. Teacher, teacher librarian, tertiary lecturer, critic, editor, author and publisher Walter McVitty was born in Melbourne in 1934 and has been involved in the field of children’s literature for over four decades. He taught in schools in Victoria and worked overseas for five years before undertaking a librarianship course at Melbourne Teachers College in 1962. He was a teacher librarian in Victoria for six years, then Senior Lecturer in children's literature at Melbourne Teachers College for fifteen years before establishing his own small publishing company, Walter McVitty Books, with his wife Lois in 1985. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book Of

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy John Sands Illus. Walter Cunninghan Five to Eight Years: MEILLON, Jill The Children’s Garden Australasian Publishing BASSER, Veronica The Glory Bird John Sands Illus. Elaine Haxton Eight to Twelve Years: GRIFFIN, David The Happiness Box Australasian Publishing Illus. Leslie Greener REES, Leslie The Story of Sarli the Turtle John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham McFADYEN, Ella Pegman’s Tales Angus & Robertson Illus. Edina Bell WILLIAMS, Ruth C. Timothy Tatters Bilson Honey Pty Illus. Rhys Williams Teenage: BIRTLES, Dora Pioneer Shack Shakespeare Head 1948 – WINNER HURLEY, Frank Shackleton's Argonauts Angus & Robertson HIGHLY COMMENDED MARTIN, J.H. & W.D. The Australian Book of Trains Angus & Robertson JACKSON, Ada Beatles Ahoy! Paterson Press Illus. Nina Poynton (chapter headings) MORELL, Musette Bush Cobbers Australasian Publishing Illus. -

Your Reading: a Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students

ED 337 804 CS 213 064 AUTHOR Nilsen, Aileen Pace, Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for JuniOr High and Middle School Students. Eighth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5940-0; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 347p.y Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High and Middle School Booklist. For the previous edition, see ED 299 570. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 59400-0015; $12.95 members, $16.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Boots; Junior High Schools; Junior High School Students; *Literature Appreciation; Middle Schools; Reading Interests; Reuding Material Selection; Recreational Reading; Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Middle School Students ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography for junior high and middle school students describes nearly 1,200 recent books to read for pleasure, for school assignments, or to satisfy curiosity. Books included are divided inco six Lajor sections (the first three contain mostly fiction and biographies): Connections, Understandings, Imaginings, Contemporary Poetry and Short Stories, Books to Help with Schoolwork, and Books Just for You. These major sections have been further subdivided into chapters; e.g. (1) Connecting with Ourselves: Accomplishments and Growing Up; (2) Connecting with Families: Close Relationships; (3) -

Plainsong Or Polyphony?

Plainsong or Polyphony? Australian Award‐Winning Novels of the 1990s for Adolescent Readers. Heather Voskuyl Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Certificate of Authorship / Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of the requirements for a degree. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information resources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate _____________________________________________________ i Acknowledgements I would like to thank two people for the contributions they have made to this thesis, my supervisor Rosemary Ross Johnston for challenging me and encouraging me to persist, and my husband Hans for his patience and support. I would also like to acknowledge the support and encouragement given to me by my employer, Queenwood School for Girls. ii Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Voice 6 Theoretical Perspectives 10 Adolescent Readers 22 Australian YA Novels 28 Addressing a Dear Child or a Becoming Adult? 35 Chapter 2: Who Speaks? 40 Omniscient Narrators 43 Multiple Narrators 48 Reliable Adolescent Narrator/Protagonists 54 Unreliable Adolescent Narrator/Protagonists 58 An Eclectic Mix? 60 Dangerous Spaces in Between 70 Chapter 3: Who Speaks to Whom? 76 Narratees 77 Subordinate Adolescent Characters – Friends and Foes 92 Chapter -

K-9 Booklist - Short

K-9 Booklist - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title Author Level 3986 1,2, pirate stew Howarth, Kylie K-2 28524 10 little hermit crabs Fox, Lee & McGowan, Shane (ill) K-2 825 10 little insects Cali, Davide & Pianina, V (ill) 5-6 15023 10 little rubber ducks Carle, Eric K-2 9404 100 Australian poems for children Griffith, Kathryn & Scott-Mitchell, Claire (eds) 3-4 & Rogers, Gregory (ill) 21158 100 scientists who made history Mills, Andrea & Caldwell, Stella 5-6 41505 100 things to know about food Baer, Sam & Firth, Rachel & Hall, Rose & 5-6 James, Alice & Martin, Jerome 5891 100 things to know about science Frith, Alex & Lacey, Minna & Martin, Jerome 5-6 & Melmoth, Jonathan 660416 100 ways to fly Taylor, Michelle 3-4 3094 100 women who made history: remarkable women Caldwell, Stella & Hibbert, Clare & Mills, 5-6 who shaped our world Andrea & Skene, Rona 5638 1000-year-old boy, The Welford, Ross 7-9 1477 1001 bugs to spot Doherty, G K-2 91599 1001 pirate things to spot Lloyd Jones, Rob & Gower, Teri (ill) K-2 6114 101 collective nouns Cossins, Jennifer K-2 87206 101 ways to save the earth Bellamy, David & Dann, Penny (ill) 5-6 22034 13 days of midnight Hunt, Leo 7-9 569157 13th reality, The: Hunt for dark infinity Dashner, James 7-9 24577 13th reality, The: Journal of curious letters Dashner, James 7-9 4983 1836 Do you dare: Fighting -

Recommended Reading List Recommended Reading List

Name: RECOMMENDED READING LIST © 2009 Kumon Institute of Education KIE GB Printed in Malaysia RRL_booklet0912.indd 1 09/12/21 11:03 Contents Genres For Level D and above, use the genre icons below to help you find books you will enjoy. Introduction ...................... Action & Adventure What is the Kumon Recommended Reading List? Introduction 1 Exciting tales for all ages, from The Saga of Erik the Viking Information for Parents ....2 (D-29) to The Three Musketeers (Further Reading 20). The Kumon Recommended Reading List (RRL) is a list of 380 books intended to help Kumon students find books that they will enjoy reading, and to .................. Read Together 4 Crime & Mystery encourage them to read books from a wide range of genres and styles. Level 2A ...........................8 Suspenseful stories, guaranteed to keep you guessing, like Five on a Treasure Island (D-28) and The Thirty-Nine Steps How are the Books Chosen? Level A ...........................10 (H-1). The books on the RRL have been selected because they are popular, award Level B ...........................12 Fairy Tale, Myth & Legend Amazing books full of fantastic places and feats, like The Iliad winning, or recognised literary classics. They were all available from major Level C ...........................14 and the Odyssey (F-1) and One Thousand and One Arabian online bookshops (Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Dymocks.com.au and Nights (G-27). Level D ...........................16 Waterstones.com) at the time of writing. Fantasy Level E ...........................18 Magic, adventure and imaginary worlds await readers in How are the Books Arranged? ........................... incredible books like Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone Level F 20 (E-21) and The Hobbit (H-3). -

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Peters Township School District MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR READING LEVEL POINTS I Had A Hammer: Hank Aaron... Aaron, Hank 7.1 34 Postcard, The Abbott, Tony 3.5 17 My Thirteenth Winter: A Memoir Abeel, Samantha 7.1 13 Go And Come Back Abelove, Joan 5.2 10 Saying It Out Loud Abelove, Joan 5.8 8 Behind The Curtain Abrahams, Peter 3.5 16 Down The Rabbit Hole Abrahams, Peter 5.8 16 Into The Dark Abrahams, Peter 3.7 15 Reality Check Abrahams, Peter 5.3 17 Up All Night Abrahams, Peter 4.7 10 Defining Dulcie Acampora, Paul 3.5 9 Dirk Gently's Holistic... Adams, Douglas 7.8 18 Guía-autoestopista galá.... Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 Hitchhiker's Guide To The... Adams, Douglas 8.3 13 Life, The Universe, And... Adams, Douglas 8.6 13 Mostly Harmless Adams, Douglas 8.5 14 Restaurant At The End-Universe Adams, Douglas 8.1 12 So Long, And Thanks For All Adams, Douglas 9.4 12 Watership Down Adams, Richard 7.4 30 Storm Without Rain, A Adkins, Jan 5.6 8 Thomas Edison (DK Biography) Adkins, Jan 9.4 8 Ghost Brother Adler, C. S. 6.5 7 Her Blue Straw Hat Adler, C. S. 5.5 9 If You Need Me Adler, C. S. 6.9 7 In Our House Scott Is My... Adler, C. S. 7.2 8 Kiss The Clown Adler, C. S. 6.1 8 Lump In The Middle, The Adler, C. S. 6.5 10 More Than A Horse Adler, C. -

FARROW Erin-Thesis.Pdf

Somewhere Between: The Shifting Trends in the Narrative Strategies and Preoccupations of the Young Adult Realistic Fiction Genre in Australia Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts Victoria University Erin Farrow 2017 Abstract. ‘Young adult realistic fiction’ is a classification used by contemporary publishers such as Random House, McGraw Hill Education and Scholastic, who define it as ‘stories with characters, settings, and events that could plausibly happen in true life’ (Scholastic 2014). From the first Australian young adult imprint in 1986 it has become possible to trace substantial shifts in the trends of genre. This thesis explores some of the ways that the narrative structures and preoccupations of contemporary Australian young adult realistic fiction novels have shifted, particularly in regards to the portrayal of the main protagonist’s self-awareness, the complexity of the subject matter being discussed and the unresolved nature of the novels’ endings. The significance of these shifting trends within the genre is explored by means of a creative component and an accompanying exegesis. Through my novel, Somewhere between, I aim to consider and build on the changing narrative structures and preoccupations of Australian novels of the young adult realistic fiction genre. The exegesis uses the examination of representative Australian YA novels published between 1986 and 2013 to demonstrate the shifting trends in these three main narrative structures and preoccupations. The gradual, steady, shift in the narrative structures and preoccupations of the genre away from stability and assurance gives evidence of shifting notions of childhood and adolescent subjectivity within contemporary Australian society.