UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture

Running head: KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 1 Kawaii Boys and Ikemen Girls: Constructing and Consuming an Ideal in Japanese Popular Culture Grace Pilgrim University of Florida KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 2 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………4 The Construction of Gender…………………………………………………………………...6 Explication of the Concept of Gender…………………………………………………6 Gender in Japan………………………………………………………………………..8 Feminist Movements………………………………………………………………….12 Creating Pop Culture Icons…………………………………………………………………...22 AKB48………………………………………………………………………………..24 K-pop………………………………………………………………………………….30 Johnny & Associates………………………………………………………………….39 Takarazuka Revue…………………………………………………………………….42 Kabuki………………………………………………………………………………...47 Creating the Ideal in Johnny’s and Takarazuka……………………………………………….52 How the Companies and Idols Market Themselves…………………………………...53 How Fans Both Consume and Contribute to This Model……………………………..65 The Ideal and What He Means for Gender Expression………………………………………..70 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………..77 References……………………………………………………………………………………..79 KAWAII BOYS AND IKEMEN GIRLS 3 Abstract This study explores the construction of a uniquely gendered Ideal by idols from Johnny & Associates and actors from the Takarazuka Revue, as well as how fans both consume and contribute to this model. Previous studies have often focused on the gender play by and fan activities of either Johnny & Associates talents or Takarazuka Revue actors, but never has any research -

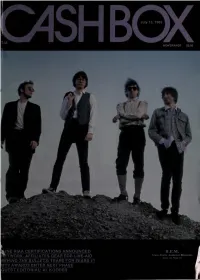

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Gary Moore: Ohne Bluesrock Kein Erfolg

EUR 7,10 DIE WELTWEIT GRÖSSTE MONATLICHE 05/07 VINYL -/ CD-AUKTION Mai Gary Moore: Ohne Bluesrock kein Erfolg. 2 Oldie-Markt 5/07 Schallplattenbörsen Plattenbörsen 2007 Schallplattenbörsen sind seit einigen Jahren fester Bestandteil der europäischen Musikszene. Steigende Besucherzahlen zeigen, dass sie längst nicht mehr nur Tummelplatz für Insider sind. Neben teuren Raritäten bieten die Händler günstige Second-Hand-Platten, Fachzeitschriften, Bücher Lexika, Poster und Zubehör an. Rund 250 Börsen finden pro Jahr allein in der Bundesrepublik statt. Oldie-Markt veröffentlicht als einzige deutsche Zeitschrift monatlich den aktuellen Börsenkalender. Folgende Termine wurden von den Veranstaltern bekannt gegeben: Datum Stadt/Land Veranstaltungs-Ort Veranstalter / Telefon 28. April Mannheim Rosengarten Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 60 28. April Halle Händelhalle First & Last (03 41) 699 56 80 29. April Trier Europahalle Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 60 29. April Braunschweig Stadthalle First & Last (03 41) 699 56 80 29. April Ulm Donauhalle Robert Menzel (07 31) 605 65 29. April Innsbruck/Österreich Hütterheim Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 5. Mai Passau X-Point Halle Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 12. Mai Karlsruhe Badnerlandhalle Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 62 12. Mai Regensburg Antonius Halle Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 13. Mai Leipzig Werk II First & Last (03 41) 699 56 80 13. Mai München Elserhalle Skull Concerts (089) 45 67 87 56 19. Mai Salzburg/Österreich Kleingmainer Saal Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 20. Mai Köln Theater am Tanzbrunnen Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 62 27. Mai Neerkant/Holland De Moost Oldies Club (00 31) 774 65 35 69 Achtung! An Alle Leser! Einsendeschluss für die Aution 343 ist der 14. -

Meyer Tech Pak012617.Indd

• Technical Information • Policies & Procedures • Fee Schedule for Rental & Services LOAD-IN AREA The loading dock is located on stage level, directly off upstage right. The dock has one 8’-0” wide x 10’-0” high (2.44m x 3.05m) overhead door. Dock height is 24” (.61m). There is NO leveler, and there is NO truck ramp. The loading area is 16’ wide x 22’ long with 12’ ceilings, in a wedge shape. Access to stage is through a 10’ wide x 11’ high overhead door upstage right. Access to the dressing rooms is by stairs or by elevator. CARPENTRY Seating Capacity Maximum Capacity: 1011 Orchestra 537 Grand Tier: 90 Mezzanine: 384 Handicapped Accessible: 8 Additional on Grand Tier Level Stage Dimensions Proscenium w: 49’-6” (15.09m) h:23’-0” (7.01m) Depth (plaster to back wall) 28’-0” (8.53m) Apron Curved 5’-0” (1.52m) at centerline Wing Space • Stage right 10’-0” (~3.05m) • Stage left 13’-0” (~3.96m) Orchestra Pit none Stage to Audience 4’-0” (1.21m) NFORMATION Stage Floor Material: 1/4” hardboard (Duron) I Color: Black Condition: Good Sub floor: 1 layer of 3/4” plywood 2x4 sleepers (24” O.C.) on resilient pads House Drapery: House Curtain- Scarlet; Manual Fly Item Number Material WxH Legs 8 black velour 10’ x 25’ (3.05m x 7.62m) Borders 4 black velour 60’ x 10’ (18.23m x 3.05m) Full Black 2 black velour 60’ x 25’ (18.23m x 7.62m) Line Set Data: Grid height: 53’-9” (16.38m) High trim: 50’-11” (15.52m) Low trim: 5’-8” (1.72m) Total Line Sets: 26 single purchase Arbor Capacity: 1500 lbs (680kg) ECHNICAL Weight Available: 8702 lbs (3947kg) Weight Size: 19 lbs (8.6 kg) Pipe Length: 60’-0” (18.29m) T Pipe size: 26 @ 1-1/2” Schedule 40 Lock Rail: Stage Left, stage level Line Plot: Enclosed Shop Area: There is NO on-site scenery shop, and there is no off-stage area for working on scenery. -

The Korean Wave As a Localizing Process: Nation As a Global Actor in Cultural Production

THE KOREAN WAVE AS A LOCALIZING PROCESS: NATION AS A GLOBAL ACTOR IN CULTURAL PRODUCTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Ju Oak Kim May 2016 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Department of Journalism Nancy Morris, Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Patrick Murphy, Associate Professor, Department of Media Studies and Production Dal Yong Jin, Associate Professor, School of Communication, Simon Fraser University © Copyright 2016 by Ju Oak Kim All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation research examines the Korean Wave phenomenon as a social practice of globalization, in which state actors have promoted the transnational expansion of Korean popular culture through creating trans-local hybridization in popular content and intra-regional connections in the production system. This research focused on how three agencies – the government, public broadcasting, and the culture industry – have negotiated their relationships in the process of globalization, and how the power dynamics of these three production sectors have been influenced by Korean society’s politics, economy, geography, and culture. The importance of the national media system was identified in the (re)production of the Korean Wave phenomenon by examining how public broadcasting-centered media ecology has control over the development of the popular music culture within Korean society. The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS)’s weekly show, Music Bank, was the subject of analysis regarding changes in the culture of media production in the phase of globalization. In-depth interviews with media professionals and consumers who became involved in the show production were conducted in order to grasp the patterns that Korean television has generated in the global expansion of local cultural practices. -

Annual Report 2003 Annual04c 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 1

Annual04C 5/23/05 4:17 PM Page 1 MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM Annual Report 2003 Annual04C 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 1 2004 Annual Report Contents Board of Trustees 2 Board Committees 2 President’s Report 5 Director’s Report 6 Curatorial Report 8 Exhibitions, Traveling Exhibitions 10 Loans 11 Acquisitions 12 Publications 33 Attendance 34 Membership 35 Education and Programs 36 Year in Review 37 Development 44 MAM Donors 45 Support Groups 52 Support Group Officers 56 Staff 60 Financial Report 62 Independent Auditors’ Report 63 This page: Visitors at The Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition. Front Cover: Milwaukee Art Museum, Quadracci Pavilion designed by Santiago Calatrava. Back cover: Josiah McElheny, Modernity circa 1952, Mirrored and Reflected Infinitely (detail), 2004. See listing p. 18. www.mam.org 1 Annual04C 5/23/05 3:55 PM Page 2 BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEES OF Earlier European Arts Committee David Meissner MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim Quirk Joanne Murphy Chair Dorothy Palay As of August 31, 2004 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Barbara Recht Sheldon B. Lubar Martha R. Bolles Vicki Samson Sheldon B. Lubar Chair Vice Chair and Secretary Suzanne Selig President Reva Shovers Christopher S. Abele Barbara B. Buzard Dorothy Stadler Donald W. Baumgartner Donald W. Baumgartner Joanne Charlton Vice President, Past President Eric Vogel Lori Bechthold Margaret S. Chester Hope Melamed Winter Frederic G. Friedman Frederic G. Friedman Stephen Einhorn Jeffrey Winter Assistant Secretary and Richard J. Glaisner George A. Evans, Jr. Terry A. Hueneke Eckhart Grohmann Legal Counsel EDUCATION COMMITTEE Mary Ann LaBahn Frederick F. -

Disney's the Little Mermaid

Disney’s The Little Mermaid A production by Variety Children’s Theatre October 24 - 26, 2014 Touhill Performing Arts Center University of Missouri - St. Louis Dear Educators, Variety Children’s Theatre is proud to present its sixth annual production, Disney’s The Little Mermaid. Once again under the direction of Tony Award nominee Lara Teeter, this show boasts some of the city’s greatest professional actors and designers. We all eagerly await the results of their craft— bringing the story of Ariel to life. Be sure that you and your students are there to experience the beauty of an opera house with a full orchestra, dazzling sets and brilliant costumes (including a trip under the sea). Musical theatre can enhance learning on so many levels. It builds an appreciation for the arts, brings to life a lesson on the parts of a story (i.e. characters, plot, conflict) and provides the perfect setting to learn a thing or two about fairy tales and why they are important windows into important facets of our lives. Variety takes that learning one step further, however, presenting an inclusive cast where adult equity actors, talented adults from community theatre, and gifted theatrical children, work side-by-side with children who have a wide range of disabilities. The production is truly a lesson in acceptance, perseverance and the “I CAN” spirit that shines through all Variety programs. In the near future, we will have Disney’s The Little Mermaid study guide to help you incorporate the show into your curriculum and to help your students prepare for the show. -

Imagem E Pensamento Comunicação E Sociedade

imagenepensamento.qxp:Apresentação 1 31/03/11 13:28 Página1 23 Comunicação e Sociedade José Bragança de Miranda, Moisés de Lemos Martins Moisés de Lemos Martins Madalena Oliveira Jacinto Godinho José Bragança de Miranda Madalena Oliveira Aparentemente a imagem superou o pensamento, já não Jacinto Godinho necessitando dele. Trata-se de um resultado paradoxal, se repararmos que a filosofia ocidental, a de Platão, por Imagem e Pensamento exemplo, começa precisamente num conflito com as ima- gens. Esse conflito é resolvido através das ideias eternas, Imagem e Pensamento um procedimento que abre caminho ao «conceito», de que a técnica digital é a culminação. No momento final deste processo, a relação entre imagem, palavra e texto tornou- -se praticamente num enigma, sendo nosso propósito, neste ensaio plural, escrito a muitas mãos, interrogá-lo, debatê-lo e clarificá-lo, na medida do possível. www.ruigracio.com Universidade do Minho Grácio Editor Grácio Editor Centro de Estudos de Comunicação e Sociedade Imagem e Pensamento:Layout 1 31/03/11 12:52 Página2 Imagem e Pensamento:Layout 1 31/03/11 12:52 Página3 Moisés de Lemos Martins, José Bragança de Miranda, Madalena Oliveira e Jacinto Godinho (Eds) IMAGEM E PENSAMENTO Grácio Editor Imagem e Pensamento:Layout 1 31/03/11 12:52 Página4 Ficha técnica Título: Imagem e Pensamento Editores: Moisés de Lemos Martins, José Bragança de Miranda, Madalena Oliveira e Jacinto Godinho Colecção: Comunicação e Sociedade — n.º 23 Director da colecção: Moisés de Lemos Martins Centro de Estudos Comunicação e Sociedade da Universidade do Minho Capa: Grácio Editor Coordenação editorial: Rui Grácio Design gráfico: Grácio Editor Impressão e acabamento: Tipografia Lousanense 1ª Edição: Abril de 2011 ISBN: 978-989-8377-12-8 Dep. -

Agriculture Architecture & Construction

FOR LANCASTER COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT PAGE 2 COURSEGUIDE SCHEDULE CHANGES A CHALLENGE AGRICULTURE Prepare to succeed Agricultural mill or lumber company. You’ll build skills in the operation of When changes should be made You’ve heard the question a thou- Mechanics & Technology mechanized harvesting equip- sand times – “What do you want to ment and its maintenance. At the end of this school year, review your choices. Prerequisite: Agricultural Science & You need to change your schedule then only if do after you graduate?” Technology Grades: 10-11 Horticulture u a counselor finds that your selections aren’t ap- If you’re like I was in high school, Credit: 1 unit Introduction propriate Offered: Andrew Jackson, Buford, Prerequisite: Agricultural Science & you really don’t know. Indian Land Technology (at Andrew Jackson and u you have failed a course And the good news is, right now, Buford) You’ll learn about agricul- u tural occupations as you learn Grades: 10-12 you’ve chosen a course that won’t be offered you don’t have to know. Credit: 1 unit more about FFA and how it u you don’t meet prerequisites. But that doesn’t mean you Offered: Andrew Jackson, Buford, supports industries. Indian Land shouldn’t be thinking about it – ex- You’ll get an overview of You’ll study house plants, What a counselor says topics covered in detail in fruit crops, landscaping and ploring careers, discovering your “You need to realize that wanting to be in classes Horticulture and Forestry so greenhouses. strengths and your interests, learn- with friends or with specific teachers or to have you can decide if you want to You’ll learn plant identifica- ing all you can so you’ll have lots of certain periods free are not valid reasons to ask to take any of these courses. -

LHAT 40Th Anniversary National Conference July 17-20, 2016

Summer 2016 Vol. 39 No. 2 IN THE LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES LEAGUE LHAT 40th Anniversary National Conference 9 Newport Drive, Ste. 200 Forest Hill, MD 21050 July40th 17-20, ANNUAL 2016 (T) 443.640.1058 (F) 443.640.1031 WWW.LHAT.ORG CONFERENCE & THEATRE TOUR ©2016 LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES. Chicago, IL ~ JULY17-20, 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Greetings from Board Chair, Jeffery Gabel 2016 Board of Directors On behalf of your board of directors, welcome to Chicago and the L Dana Amendola eague of Historic American Theatres’ 40th Annual Conference Disney Theatrical Group and Theatre Tour. Our beautiful conference hotel is located in John Bell the heart of Chicago’s historic theatre district which has seen FROM it all from the rowdy heydays of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to Tampa Theatre Randy Cohen burlesque and speakeasies to the world-renowned Lyric Opera, Americans for the Arts Steppenwolf Theatre and Second City. John Darby The Shubert Organization, Inc. I want to extend an especially warm welcome to those of you Michael DiBlasi, ASTC who are attending your first LHAT conference. You will observe old PaPantntaggeses Theh attrer , LOL S ANANGGELEL S Schuler Shook Theatre Planners friends embracing as if this were some sort of family reunion. That’s COAST Molly Fortune because, for many, LHAT is a family whose members can’t wait Newberry Opera House to catch up since last time. It is a family that is always welcoming Jeffrey W. Gabel new faces with fresh ideas and even more colorful backstage Majestic Theater stories. -

The Musical Worlds of Julius Eastman Ellie M

9 “Diving into the earth”: the musical worlds of Julius Eastman ellie m. hisama In her book The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism, Briony Fer considers the dramatic changes to “the map of art” in the 1950s and characterizes the transition away from modernism not as a negation, but as a positive reconfiguration.1 In examining works from the 1950s and 1960s by visual artists including Piero Manzoni, Eva Hesse, Dan Flavin, Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, and Louise Bourgeois, Fer suggests that after a modernist aesthetic was exhausted by mid-century, there emerged “strategies of remaking art through repetition,” with a shift from a collage aesthetic to a serial one; by “serial,” she means “a number of connected elements with a common strand linking them together, often repetitively, often in succession.”2 Although Fer’s use of the term “serial” in visual art differs from that typically employed in discussions about music, her fundamental claim I would like to thank Nancy Nuzzo, former Director of the Music Library and Special Collections at the University at Buffalo, and John Bewley, Archivist at the Music Library, University at Buffalo, for their kind research assistance; and Mary Jane Leach and Renée Levine Packer for sharing their work on Julius Eastman. Portions of this essay were presented as invited colloquia at Cornell University, the University of Washington, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Peabody Conservatory of Music, the Eastman School of Music, Stanford University, and the University of California, Berkeley; as a conference paper at the annual meeting of the Society for American Music, Denver (2009), and the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music, Kansas City (2009); and as a keynote address at the Michigan Interdisciplinary Music Society, Ann Arbor (2011). -

THE ARMITAGE BALLET • MEREDITH MONK an ARTIST and HER MUSIC BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

~'f& •. & OF MUSIC THE ARMITAGE BALLET • MEREDITH MONK AN ARTIST AND HER MUSIC BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer BAM Carey Playhouse November 20-22, 1987 presents MEREDITH MONK AN ARTIST AND HER MUSIC with ALLISON EASTER WAYNE HANKIN ROBERTEEN NAAZ HOSSEINI CHING GONZALEZ NICKY PARAISO ANDREA GOODMAN NURIT TILLES and guest artist BOBBY McFERRIN Music Composed by Lighting Designed by MEREDITH MONK· TONY GIOVANNETTI Costumes Designed by 1echnical Director Stage Manager YOSHIO YABARA DAVID MooDEY PEGGY GOULD Sound 1echnician Costume Assistant DAVE MESCHTER ANNEMARIE HOLLANDER Meredith Monk: An Artist And Her Music is presented in association with THE HOUSE FOUNDATION FOR THE AIUS, INC. The music events of the NEXT WAVE Festival are made possible, in part, with a grant from the MARY FLAGLER CARY CHARITABLE TRUST BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC E i ;II-----,FEIS;~AL·1 SPONSORED BY PHILIP MORRIS COMPANIES INC. The 1987 NEXT WAVE Festival is sponsored by PllILIPMORRISCOMPANIES INC. The NEXT WAVE Production and Touring Fund and Festival are supported by: the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FORTIlE AKfS, TIlEROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION, TIlEFORD FOUNDATION, TIlE ELEANOR NAYWR DANA CHARITABLE TRUST, PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS, the BOOI'II FERRIS FOUNDATION, TIlE IlENRYLuCEFOUNDATlON, INC., theAT&if FOUNDATION, TIlEHOWARD GILMAN FOUNDATION, TIlEWILLIAM AND FIDRA HEWLEITFOUNDATlON, theMARY FLAGLER CARY CHARITAl'LETRUST, TllEHINDUJAFOUNDATlON, TIlEEDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION OFAMERICA, the MORGAN GUARANTY TRUST coMPANY, ROBERI' w. WILSON, 'DIEREFJ)FOUNDATION INC., theEMMA A. SIIEAFERCHARITABLE TRUST, SCHLUMBERGER, YVES SAINT LAURENT INTERNATIONAL, andtheNEW lQRK STATE COUNCD.. ON TIlE AR1K Additional funds for the NEXT WAVE Festival are provided by: TIlEBEST PRODUcm FOUNDATION, C~OLA ENTEKI'AINMENT, INC., MEET TIlECOMPOSER, INC., the CIGNA CORPORATION, TIlEWILLIAM AND MARY GREVE FOUNDATION, INC., the SAMUEL I.