Blue Bloods’ and Other Shows Resumed Filming in Pandemic N.Y.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14,000 Rsf Available for Lease

vk LOFTS// ON 37TH 35-18 37TH STREET A RARE ASSET IN ONE OF THE MOST DESIRABLE LOCATIONS OUTSIDE OF MANHATTAN. 14,000 RSF AVAILABLE FOR LEASE 1 2 SURROUNDING AREA vk LOFTS// ON 37TH STREET Lexus of Queens Standard Motor Products Building (Coffeed & Brooklyn Grange located on Rooftop) 3 PROPERTY INFORMATION • 35-18 37th Street, Astoria, NY vk • 7,000 SF - 2nd Floor LOFTS// ON 37TH • 7,000 SF - 3rd Floor STREET • Immediate occupancy • New bathrooms • New windows • Natural light • One large freight elevator • One exterior loading dock • 24/7 building access • Fully sprinklered 2018 Estimated Demographics .5 miles 1 mile 2 miles POPULATION 30,188 137,938 466,361 AVERAGE HOUSEHOLD INCOME $80,785 $78,615 $110,061 DAYTIME POPULATION 29,032 126,054 503,177 4 FLOOR PLANS SECOND FLOOR THIRD FLOOR WARNING: It is a violation of the WARNING: It is a violation of the law for any person, unless acting law for any person, unless acting under the direction of a licensed under the direction of a licensed architect to alter any item in any architect to alter any item in any way. If an item bearing the seal of way. If an item bearing the seal of an architect is altered, the an architect is altered, the altering architect shall affix to altering architect shall affix to this item his seal and the notation this item his seal and the notation "altered by" followed his signature "altered by" followed his signature and the date of such alteration. and the date of such alteration. OWNERSHIP AND USE OF OWNERSHIP AND USE OF DOCUMENTATION: drawings and DOCUMENTATION: drawings and specifications, as instruments of specifications, as instruments of professional service, are and professional service, are and shall remain the property of the shall remain the property of the architect. -

Latino Representation on Primetime Television in English and Spanish Media: a Framing Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2017 Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis Gabriela Arellano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arellano, Gabriela, "Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis" (2017). Master's Theses. 4785. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.2wvs-3sd3 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gabriela Arellano May 2017 © 2017 Gabriela Arellano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATIONS SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 Dr. Diana Stover School of Journalism and Mass Communications Dr. William Tillinghast School of Journalism and Mass Communications Professor John Delacruz School of Journalism and Mass Communications ABSTRACT LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano The purpose of this study was to provide updated data on the Latino portrayals on primetime English and Spanish-language television. -

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography Alexnepomniaschy.Com

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography alexnepomniaschy.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE MARVELOUS MRS. MAISEL Daniel Palladino AMAZON STUDIOS / Nick Thomason Season 4 Amy Sherman-Palladino MIXTAPE Ti West ANNAPURNA PICTURES Series NETFLIX / Chip Vucelich, Josh Safran L.A.’S FINEST Eagle Egilsson SONY PICTURES TELEVISION Series Mark Tonderai Scott White, Jerry Bruckheimer WISDOM OF THE CROWD Adam Davidson CBS Series Jon Amiel Ted Humphrey, Vahan Moosekian Milan Cheylov Adam Davidson GILMORE GIRLS: A YEAR IN THE LIFE Amy Sherman- WARNER BROS. TV / NETFLIX Mini-series Palladino Daniel Palladino Daniel Palladino Amy Sherman-Palladino THE AMERICANS Thomas Schlamme DREAMWORKS / FX Season 4 Chris Long Mary Rae Thewlis, Chris Long Daniel Sackheim Joe Weisberg, Joel Fields THE MENTALIST Chris Long WARNER BROS. / CBS Season 7 Simon Baker Matthew Carlisle, Bruno Heller Nina Lopez-Corrado Chris Long STANDING UP D.J. Caruso ALDAMISA Janet Wattles, Jim Brubaker Ken Aguado, John McAdams BLUE BLOODS David Barrett CBS Seasons 4 & 5 John Behring Jane Raab, Kevin Wade Alex Chapple Eric Laneuville I AM NUMBER FOUR D.J. Caruso DREAMWORKS Add’l Photography Sue McNamara, Michael Bay BIG LOVE Daniel Attias HBO Season 4 David Petrarca Bernie Caulfield THE EDUCATION OF CHARLIE BANKS Fred Durst Marisa Polvino, Declan Baldwin TAKE THE LEAD Liz Friedlander NEW LINE Diane Nabatoff, Michelle Grace CRIMINAL MINDS Pilot Richard Shepherd CBS / Peter McIntosh NARC Joe Carnahan PARAMOUNT PICTURES Nomination, Best Cinematography – Ind. Spirit -

COLEMAN, ROSALYN 2020 Resume

ROSALYNFilm COLEMAN THE IMMORTAL JELLYFISH Dusty Bias MISS VIRGINIA R.J. Daniel Hanna EVOLUTION OF A CRIMINAL Darious Clarke Monroe/Spike Lee Producer IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY Ryan Fleck & Ana Bolden TWELVE Joel Schumacher FRANKIE & ALICE (w/Halle Berry) Geoffrey Sax BROOKLYN’S FINEST Antwoine Fuqua/Warner Bros. BROWN SUGAR (w/Taye Diggs) Rick Famuyiwa/20th Century Fox VANILLA SKY (w/Tom Cruise) Cameron Crowe/ Artisan OUR SONG (w/Kerry Washington) Jim McKay/Stepping Pictures MUSIC OF THE HEART (w/Meryl Streep) Wes Craven/Miramax MIXING NIA Alison Swan/Independent PERSONALS Mike Sargent/Independent Television JESSICA JONES Netflix BULL CBS MADAM SECRETARY CBS BLUE BLOODS CBS ELEMENTARY CBS WHITE COLLAR USA SPRING/FALL (Pilot) HBO Pilot NURSE JACKIE Showtime MERCY (Pilot) NBC NEW AMSTERDAM FOX KIDNAPPED (recurring) NBC LAW & ORDER SVU & CI NBC/Jim McKay/Michael Zinberg DEADLINE NBC OZ (recurring) HBO/Alex Zakrzewski D.C. (recurring) WB/Dick Wolf producer THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards/Hallmark Hall of Fame THE DITCHDIGGER’S DAUGHTERS Johnny Jensen/Family Channel Broadway TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD Bartlett Shear TRAVESTIES us Patrick Marber/Roundabout Theatre Co. THE MOUNTAINTOP us Kenny Leon RADIO GOLF us Kenny Leon SEVEN GUITARS Lloyd Richards THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards MULE BONE Michael Shultz Off Broadway NATIVE SON Acting Company/Yale Rep/ Seret Scott SCHOOL GIRLS OR THE AFRICAN MEAN GIRLS PLAY us MCC /Rebecca Taichman PIPELINE us Lincoln Center Theatre/Lileana Blain-Cruz BREAKFAST WITH MUGABE Signature Theater/David Shookov ZOOMAN & THE SIGN Signature Theatre/Steven Henderson WAR Rattlestick Theatre/Anders Cato THE SIN EATER 59 E. -

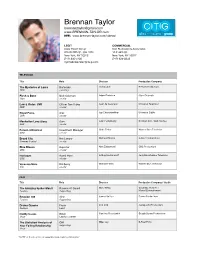

Brennan Taylor [email protected] REEL

Brennan Taylor [email protected] www.BRENNAN-TAYLOR.com REEL www.brennan-taylor.com/videos/ LEGIT COMMERCIAL Clear Talent Group Don Buchwald & Associates 325 W 38th St., Ste 1203 10 E 44th St. New York, NY 10018 New York, NY 10017 (212) 840-4100 (212) 634-8348 [email protected] TELEVISION Title Role Director Production Company The Mysteries of Laura Bartender Randy Zisk Berlanti Productions NBC recurring Flesh & Bone Nick Coleman Adam Davidson Starz Originals Starz co-star Law & Order: SVU Officer Tom Haley Jean de Segonzac Universal Television NBC co-star Royal Pains Alex Jay Chandrasekhar Universal Cable USA co-star Manhattan Love Story Sam John Fortenberry Brillstein Ent. / ABC Studios ABC co-star Person of Interest Investment Manager Chris Fisher Warner Bros Television CBS co-star Broad City Hot Lawyer Michael Blieden 3 Arts Entertainment Comedy Central co-star Blue Bloods Reporter Alex Zakrzewski CBS Productions CBS co-star Hostages Agent Horn Jeffrey Nachmanoff Jerry Bruckheimer Television CBS co-star Veronica Mars RA Gerry Michael Fields Warner Bros Television CW co-star FILM Title Role Director Production Company / Studio The Amazing Spider-Man II Ravencroft Guard Marc Webb Columbia Pictures / Feature Supporting Marvel Entertainment Reunion 108 Allen James Suttles Carms Productions Feature Supporting Drama Queens Frank Levi Lieb Juxtaposed Productions Feature Lead Daddy Issues Dillon Carolina Roca-Smith Grizzly Bunny Productions Short Lead & co-writer The Statistical Analysis of Cliff Miles Jay B-Reel Films Your Failing Relationship Supporting Short *A PDF of this is online at: www.brennan-taylor.com/resume/. -

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Sanibona Bangane! South Africa

2003 ANNUAL REPORT sanibona bangane! south africa Takalani Sesame Meet Kami, the vibrant HIV-positive Muppet from the South African coproduction of Sesame Street. Takalani Sesame on television, radio and through community outreach promotes school readiness for all South African children, helping them develop basic literacy and numeracy skills and learn important life lessons. bangladesh 2005 Sesame Street in Bangladesh This widely anticipated adaptation of Sesame Street will provide access to educational opportunity for all Bangladeshi children and build the capacity to develop and sustain quality educational programming for generations to come. china 1998 Zhima Jie Meet Hu Hu Zhu, the ageless, opera-loving pig who, along with the rest of the cast of the Chinese coproduction of Sesame Street, educates and delights the world’s largest population of preschoolers. japan 2004 Sesame Street in Japan Japanese children and families have long benefited from the American version of Sesame Street, but starting next year, an entirely original coproduction designed and produced in Japan will address the specific needs of Japanese children within the context of that country’s unique culture. palestine 2003 Hikayat Simsim (Sesame Stories) Meet Haneen, the generous and bubbly Muppet who, like her counterparts in Israel and Jordan, is helping Palestinian children learn about themselves and others as a bridge to cross-cultural respect and understanding in the Middle East. egypt 2000 Alam Simsim Meet Khokha, a four-year-old female Muppet with a passion for learning. Khokha and her friends on this uniquely Egyptian adaptation of Sesame Street for television and through educational outreach are helping prepare children for school, with an emphasis on educating girls in a nation with low literacy rates among women. -

SOUND STAGE PRODUCTION REPORT “This Report Reveals a Portion of the Los Angeles Production Picture That Has Until Now Gone Unviewed

SOUND STAGE PRODUCTION REPORT “This report reveals a portion of the Los Angeles production picture that has until now gone unviewed. We hope that the availability of this data, and our plans to expand it through new studio partnerships, will be an asset to business leaders and policymakers, and further public understanding of L.A.’s signature industry and the wide employment and economic benefits it brings.” - Paul Audley, President of FilmL.A. PHOTO: Dmitry Morgan / Shutterstock.com PHOTO: MBS Media Campus PHOTO: Sunset Gower Studios© 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. CREDITS: 12th Floor Supervising Research Analyst: Hollywood, CA 90028 Adrian McDonald Graphic Design: filmla.com Shane Hirschman Photography: @FilmLA Shutterstock FilmLA Stages / studios (as noted) FilmLAinc TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 CERTIFIED SOUND STAGES IN GREATER LOS ANGELES 3 OTHER NON-CERTIFIED PRODUCTION SPACES 3 SHOOT DAYS ON STUDIO SOUND STAGES AND BACKLOTS 4 TRENDS IN SOUND STAGE FILMING 5 TRENDS IN BACKLOT FILMING 7 TRENDS IN SOUND STAGE OCCUPANCY 8 PROJECT COUNTS BY PRODUCTION CATEGORY 8 SOUND STAGES AND STUDIO INFRASTRUCTURE IN NORTH AMERICA 9 CONCLUSION 12 INTRODUCTION For more than 20 years, FilmL.A. has conducted an ongoing study of on-location filming in the Greater Los Angeles area. Drawing on data from film permits it coordinates, FilmL.A. publishes detailed quarterly updates on local film production, covering categories like Feature Films, Television Dramas and Commercials, among others. The availability of this data helps inform the film industry, Los Angeles area residents and state and local public officials of the overall health of California’s signature industry. Few other film offices track local film production as thoroughly as FilmL.A does. -

From Museums to Film Studios, the Creative Sector Is One of New York City’S Most Important Economic Assets

CREATIVE NEW YORK From museums to film studios, the creative sector is one of New York City’s most important economic assets. But the city’s working artists, nonprofit arts groups and for-profit creative firms face a growing number of challenges. June 2015 www.nycfuture.org CREATIVE NEW YORK Written by Adam Forman and edited by David Giles, Jon- CONTENTS athan Bowles and Gail Robinson. Additional research support from from Xiaomeng Li, Travis Palladino, Nicho- las Schafran, Ryan MacLeod, Chirag Bhatt, Amanda INTRODUCTION 3 Gold and Martin Yim. Cover photo by Ari Moore. Cover design by Amy ParKer. Interior design by Ahmad Dowla. A DECADE OF CHANGE 17 Neighborhood changes, rising rents and technology spark This report was made possible by generous support anxiety and excitement from New York Community Trust, Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, Rock- SOURCES OF STRENGTH 27 efeller Brothers Fund and Edelman. Talent, money and media make New York a global creative capital CENTER FOR AN URBAN FUTURE CREATIVE VOICES FROM AROUND THE WORLD 33 120 Wall St., Fl. 20 New YorK, NY 10005 Immigrants enrich New York’s creative sector www.nycfuture.org THE AFFORDABILITY CRISIS 36 Center for an Urban Future is a results-oriented New Exorbitant rents, a shortage of space and high costs York City-based think tank that shines a light on the most critical challenges and opportunities facing New ADDITIONAL CHALLENGES 36 YorK, with a focus on expanding economic opportunity, New York City’s chief barriers to variety and diversity creating jobs and improving the lives of New York’s most vulnerable residents. -

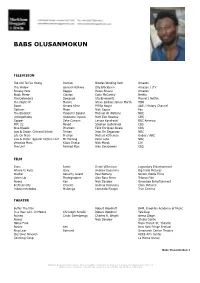

Babs Olusanmokun

BABS OLUSANMOKUN TELEVISION Too Old To Die Young Damian Nicolas Winding Refn Amazon The Widow General Azikiwe Olly Blackburn Amazon / ITV Sneaky Pete Reggie Helen Shaver Amazon Black Mirror Clayton Colm McCarthy Netflix The Defenders Sowande Uta Briesewitz Marvel / Netflix The Night Of Marvin Steve Zaillian/James Marsh HBO Roots Omoro Kinte Phillip Noyce A&E / History Channel Gotham Mace Nick Copus Fox The Blacklist Yaabari's Soldier Michael W. Watkins NBC Unforgettable Goodacre Oyensi Matt Earl Beesley CBS Copper Zeke Canaan Larysa Kondracki BBC America NYC 22 Fouad Stephen Gyllenhaal CBS Blue Bloods Phantom Félix Enríquez Alcalá CBS Law & Order: Criminal Intent Tristan Jean De Segonzac NBC Life On Mars Preston Michael Katleman Kudos / ABC Law & Order: Special Victims Unit Mr Marong Peter Leto NBC Veronica Mars Kizza Oneko Nick Marck CW The Unit Painted Man Alex Zakrzewski CBS FILM Dune Jamis Denis Villeneuve Legendary Entertainment Where Is Kyra Gary Andrew Dosunmu Big Indie Pictures Shelter Security Guard Paul Bettany Screen Media Films Listen Up Photographer Alex Ross Perry Tribeca Film Ponies Ken Nick Sandow Greenbox Entertainment Restless City Cravate Andrew Dosunmu Clam Pictures Indocumentados Mubenga Leonardo Ricagni True Cinema THEATER Buffer The Man Robert Woodruff BAM, Brooklyn Academy of Music In a Year with 13 Moons Christoph Smolik Robert Woodruff Yale Rep Ruined Cmdr. Osembenga Charles R. Wright Arena Stage Ponies Nick Sandow Studio Dante Home Free Mass Transit St. Theatre Ponies Ken New York Fringe Festival King Lear Edmund Greenwich Center Theatre Sky Over Nineveh HERE Arts Center Counting Coup La Mama Annex Babs Olusanmokun 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Bank Gallery, High Street, Kenilworth, Warwickshire, CV8 1LY Registered in England No. -

LIC Comprehensive Plan Phase 1

LONG ISLAND CITY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PHASE 1 LONG ISLAND CITY Phase Comprehensive Plan 1 SUMMARY REPORT 1 LONG ISLAND CITY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PHASE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Long Island City Comprehensive Plan has received pivotal support from public and private funders: NYS Senator Michael Gianaris NYC Economic Development Corporation NYS Assemblywoman Catherine Nolan Consolidated Edison Co. of N.Y., Inc. NYC Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito Cornell Tech NYC Council Majority Leader Jimmy Van Bramer Ford Foundation Queens Borough President Melinda Katz TD Charitable Foundation Empire State Development Verizon Foundation NYC Regional Economic Development Council The LICP Board Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee provided invaluable input, feedback and support. Members include, Michelle Adams, Tishman Speyer Richard Dzwlewicz, TD Bank Denise Arbesu, Citi Commercial Bank Meghan French, Cornell Tech David Brause, Brause Realty John Hatfield, Socrates Sculpture Park Tracy Capune, Kaufman Astoria Studios, Inc. Gary Kesner, Silvercup Studios Mary Ceruti, SculptureCenter Seth Pinsky, RXR Realty Ebony Conely-Young, Long Island City YMCA Caryn Schwab, Mount Sinai Queens Carol Conslato, Consolidated Edison Co. of N.Y., Inc. Gretchen Werwaiss, Werwaiss & Co., Inc. Jenny Dixon, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation Jonathan White, White Coffee Corporation and Garden Museum Richard Windram, Verizon Patricia Dunphy, Rockrose Development Corp. Finally, thank you to the businesses and organizations who responded to our survey and to everyone who participated in our focus groups and stakeholder conversations. Your participation was essential to informing this report. Summaries and lists of participants can be found in the Appendices. 2 LONG ISLAND CITY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN PHASE 1 ABOUT THIS REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Phase 1 of the Comprehensive Plan and this report was completed by Long Island City Partnership with the assistance of Public Works Partners and BJH Advisors. -

A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE CLOSER AND SAVING GRACE: FEMINIST AND GENRE THEORY IN 21ST CENTURY TELEVISION Lelia M. Stone, B.A., M.P.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Albert Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Art Goven, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stone, Lelia M. A Textual Analysis of The Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21st Century Television. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2013, 89 pp., references 82 titles. Television is a universally popular medium that offers a myriad of choices to viewers around the world. American programs both reflect and influence the culture of the times. Two dramatic series, The Closer and Saving Grace, were presented on the same cable network and shared genre and design. Both featured female police detectives and demonstrated an acute awareness of postmodern feminism. The Closer was very successful, yet Saving Grace, was cancelled midway through the third season. A close study of plot lines and character development in the shows will elucidate their fundamental differences that serve to explain their widely disparate reception by the viewing public. Copyright 2013 by Lelia M. Stone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters Page 1 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................