Protest and Punishment Political Prisoners in Papua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi

International Center for Transitional Justice The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi June 2012 Cover: A Papuan victim shows diary entries from 1969, when he was detained and transported to Java before the Act of Free Choice. ICTJ International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi www.ictj.org iii International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi Acknowledgements The International Center for Transitional Justice and (ICTJ) and the Institute of Human Rights Studies and Advocacy (ELSHAM) acknowledges the contributions of Matthew Easton, Zandra Mambrasar, Ferry Marisan, Joost Willem Mirino, Dominggas Nari, Daniel Radongkir, Aiesh Rumbekwan, Mathius Rumbrapuk, Sem Rumbrar, Andy Tagihuma, and Galuh Wandita in preparing this paper. Editorial support was also provided by Tony Francis, Atikah Nuraini, Nancy Sunarno, Dodi Yuniar, Dewi Yuri, and Sri Lestari Wahyuningroem. Research for this document were supported by Canada Fund. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of ICTJ and ELSHAM and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. About the International Center for Transitional Justice ICTJ works to assist societies in regaining humanity in the wake of massive human rights abuses. We provide expert technical advice, policy analysis, and comparative research on transitional justice approaches, including criminal prosecutions, reparations initiatives, truth seeking and memory, and institutional reform. -

Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA

Filep Karma adalah pemimpin paling berani di Papua Barat. Dia lawan kekerasan dengan taktik non-kekerasan macam Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King dan Nelson Mandela. Eben Kirksey, antropolog, menulis buku “Freedom in Entangled Worlds: West Papua and the Architecture of Global Power” Filep Karma’s steadfast resistance is an inspiration to all those struggling for human rights and justice for West Papua and elsewhere. John M. Miller, koordinator East Timor and Indonesia Action Network di New York Filep Karma is known to many in New Zealand. He is an icon of commit- ment to justice and freedom. Maire Leadbeater dari Auckland Aotearoa menulis buku “Negligent Neighbour: New Zealand’s Complicity in the Invasion and Occupation of Timor-Leste” Seakan Kitorang Setengah BinAtang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA FILEP KARMA Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua ©Deiyai Cetakan Pertama, November 2014 Interviewer Basilius Triharyanto Firdaus Mubarik Ruth Ogetay Nona Elisabeth Editor Lovina Soenmi Tata Letak dan Disain Henry Adrian Foto Cover Depan nobodycorp.org Foto Cover Belakang Eben Kirksey Karma, Filep Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua Deiyai, Jayapura, 2014 xvi + 137 hlm; 14,5 x 21,5 cm ISBN 978-602-17071-4-2 vi DAFTAR ISI ix Pengantar: Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua oleh Jim Elmslie 1 Masa Kecil di Wamena dan Jayapura 13 Biak Berdarah 25 Nasionalisme Papua 45 Perjalanan dalam Gambar 65 Dari Penjara ke Penjara 81 Kritik Langkah Perjuangan 101 Lampiran: Keputusan UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention oleh Freedom Now 129 Epilog: Menemui Filep Karma oleh Anugerah Perkasa vii viii PENGANTAR ix SEAKAN KITORANG SETENGAH BINATANG Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua FILEP KARMA, kelahiran 1959, menjalani hidupnya dalam bayang- bayang militer Indonesia. -

The Level of Apron Utility at Sultan Hasanuddin International Airport Maros

IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN: 2278-1684,p-ISSN: 2320-334X, Volume 16, Issue 4 Ser. I (Jul. - Aug. 2019), PP 59-63 www.iosrjournals.org The Level of Apron Utility at Sultan Hasanuddin International Airport Maros Ida Umboro Wahyu Nur Wening1, M. Yamin Jinca2, Jamaluddin Rahim3 1Master Degree of Transportation Engineering, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, 2Professor for Transportation Planning, Urban and Regional Planning, Hasanuddin University, 3Lecturer, Transportation Engineering, Hasanuddin University, Makassar-Indonesia, Corresponding Author: Ida Umboro Wahyu Nur Wening Abstract: Demand for flight numbers is an important factor in planning the capacity and facility requirements at the airport. This study aims to forecast the number of airplane movements over the next 5 years using the ARIMA method, determine the utilization level of the apron with Analytical Models for Gate Capacity, and estimate the amount of parking stand (gate) needed using the formula number of airplane gates. The results showed that the best model for forecasting the number of departure and arrival flights was ARIMA (0,1,1). Th apron utility rate is 35% with the use of 40 parking stands during rush hour. The need for stand parking for the next 5 years is 55 gates. It was concluded that forecasting the number of airplane movements increased every year. The maximum capacity of 75% is 31%. Keywords: Flight Demand, Forecasting Models, Apron, Effectiveness ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- Date of Submission: 01-07-2019 Date of acceptance: 16-07-2019 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. Introduction Air transportation has become one of the important modes of transportation for medium and long distance travel. -

Papua JOHN BRAITHWAITE, MICHAEL COOKSON, VALERIE BRAITHWAITE and LEAH DUNN1

2. Papua JOHN BRAITHWAITE, MICHAEL COOKSON, VALERIE BRAITHWAITE AND LEAH DUNN1 Papua is interpreted here as a case with both high risks of escalation to more serious conflict and prospects for harnessing a ‘Papua Land of Peace’ campaign led by the churches. The interaction between the politics of the Freeport mine and the politics of military domination of Papua, and military enrichment through Papua, are crucial to understanding this conflict. Replacing the top- down dynamics of military-political domination with a genuine bottom-up dynamism of village leadership and development is seen as holding the key to realising a Papua that is a ‘land of peace’ (see Widjojo et al. 2008). Papuans have less access to legitimate economic opportunities than any group in Indonesia and have experienced more violence and torture since the late 1960s in projects of the military to block their political aspirations than any other group in Indonesia today. Institutions established with the intent of listening to Papuan voices have in practice been deaf to those voices. Calls for truth and reconciliation are among the pleas that have fallen on deaf ears, which is an acute problem when so many Papuans see Indonesian policy in Papua as genocide. Anomie in the sense of withdrawal of commitment to the Indonesian normative order by citizens, and in the sense of gaming that order by the military, is entrenched in Papua. Background to the conflict Troubled jewels of cultural and biological diversity The island of New Guinea and the smaller islands along its coast are home to nearly 1000 languages (267 on the Indonesian side) and one-sixth of the world’s ethnicities (Ruth-Hefferbower 2002:228). -

PT. Aviastar Mandiri PK – BRD British

FINAL KNKT 09.12.04.01 NNAATTIIOONNAALL TTRRAANNSSPPOORRTTAATTIIOONN SSAAFFEETTYY COOMMMMIITTTTEEEE C Aircraft Accident Investigation Report PT. Aviastar Mandiri PK – BRD British Aerospace BAe 146-300 Wamena Airport, Papua Republic of Indonesia 9 April 2009 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY COMMITTEE MINISTRY OF TRANSPORTATION REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA 2009 This Preliminary Factual Report was produced by the National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC), Karya Building 7th Floor Ministry of Transportation, Jalan Medan Merdeka Barat No. 8 JKT 10110, Indonesia. The report is based upon the investigation carried out by the NTSC in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Aviation Act (UU No.1/2009), and Government Regulation (PP No. 3/2001). Readers are advised that the NTSC investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing aviation safety. Consequently, NTSC reports are confined to matters of safety significance and may be misleading if used for any other purpose. As NTSC believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, readers are encouraged to copy or reprint for further distribution, acknowledging NTSC as the source. When the NTSC makes recommendations as a result of its investigations or research, safety is its primary consideration. However, the NTSC fully recognizes that the implementation of recommendations arising from its investigations will in some cases incur a cost to the industry. Readers should note that the information in NTSC reports and recommendations is provided to promote aviation safety. In no case is it intended to imply blame or liability. TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................................... I TABLE OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................. -

Prosecuting Political Aspiration RIGHTS Indonesia’S Political Prisoners WATCH

Indonesia HUMAN Prosecuting Political Aspiration RIGHTS Indonesia’s Political Prisoners WATCH Prosecuting Political Aspiration Indonesia’s Political Prisoners Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-642-X Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org June 2010 1-56432-642-X Prosecuting Political Aspiration Indonesia’s Political Prisoners Maps of Prisons with Political Prisoners in Indonesia ......................................................... 1 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations ....................................................................................................... -

Suharto Dies Without Being Brought to Justice

Tapol bulletin no, 188/189, March 2008 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (2008) Tapol bulletin no, 188/189, March 2008. Tapol bulletin (188). pp. 1-36. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25927/ Bulletin no.188/189 March 2008 ISSN 1356-1154 Promoting human rights, peace and democracy in Indonesia Suharto dies without being brought to justice The following statement was issued by TAPOL after the death of Suharto on 27 January 2008: It is hard to exaggerate the damage inflicted on political rights, the rule of law ceased to function and Indonesia by the form'er dictator Suharto, who died today, gross human rights violations occurred without end. during the 33 years when he ruled the country with a rod After Suharto was forced to resign when mass of iron until his downfall in May 1998. demonstrations swept Indonesia in 1998 in response to Suharto rose to power on a wave of massacres that the financial crisis engulfing the country, the political killed up to one million people, one of the twentieth constraints on the population were lifted. But the century's worst crimes against humanity for which no one damaging impact of military impunity and the lack of has been brought to justice. Tens of thousands more were incarcerated and held for more than a decade without charge or trial. 13,000 men were banished to the remote island of Buru, out of reach of their families and subject to Contents a harsh physical environment and unremitting hard labour, which caused hundreds of deaths. -

"Don't Bother, Just Let Him Die"

"DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE" KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International Indonesia 2018 Cover photo: A Papuan woman mourns the victim of shootings in Paniai Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a © Amnesty International Indonesia/Bagus Septa Pratama Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons license. First published in 2018 by Amnesty International Indonesia HDI Hive Menteng 3rd Floor, Probolinggo 18 Jakarta Pusat 10350 Index: ASA 21/8198/2018 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International Indonesia amnesty.org – amnestyindonesia.org "DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE": KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA "DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE": KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA 3 Amnesty International Indonesia CONTENTS GLOSSARY 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 2. BACKGROUND 13 3. INDONESIA’S OBLIGATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AND IN NATIONAL LEGISLATION 23 4. -

National Transportation Safety Committee Ministry of Transportation Republic of Indonesia 2009

KNKT.08.03.06.04 NNAATTIIOONNAALL TTRR AANNSSPPOORRTTAATTIIOONN SSAAFFFosterEE BrooksTTYY drunk pilot skit.wmv CCOOMMMMIITTTTEEEE Aircraft Accident Investigation Report Transall C-160 PK–VTQ Wamena Airport, Wamena, Papua Republic of Indonesia 6 March 2008 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY COMMITTEE MINISTRY OF TRANSPORTATION REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA 2009 This report was produced by the National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC), Karya Building 7th Floor Ministry of Transportation, Jalan Medan Merdeka Barat No. 8 JKT 10110, Indonesia. The report is based upon the investigation carried out by the NTSC in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, Aviation Act (UU No.1/2009), and Government Regulation (PP No. 3/2001). Readers are advised that the NTSC investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing aviation safety. Consequently, NTSC reports are confined to matters of safety significance and may be misleading if used for any other purpose. As NTSC believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, readers are encouraged to copy or reprint for further distribution, acknowledging NTSC as the source. When the NTSC makes recommendations as a result of its investigations or research, safety is its primary consideration. However, the NTSC fully recognizes that the implementation of recommendations arising from its investigations will in some cases incur a cost to the industry. Readers should note that the information in NTSC reports and recommendations is provided to promote aviation safety. In no case is it intended to imply blame or liability. TABLE OF CONTENS TABLE OF CONTENS .......................................................................................... ii FIGURES ............................................................................................................... iv GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. -

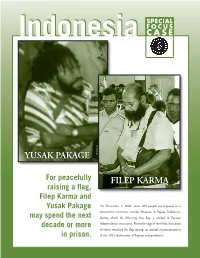

Yusak Pakage Filep Karma

SPECIAL FOCUS IndonesiaIndonesia CASE YUSAK PAKAGE ©ELSHAM For peacefully FILEP KARMA ©ELSHAM raising a flag, Filep Karma and On December 1, 2004, some 200 people participated in a Yusak Pakage nonviolent ceremony outside Abepura in Papua, Indonesia, may spend the next during which the Morning Star flag, a symbol of Papuan decade or more independence, was raised. From the edge of the fields, hundreds of others watched the flag-raising, an annual commemoration in prison. of the 1962 declaration of Papuan independence. Indonesian police advanced on the crowd, firing shots and beating people with batons. At least four people were reportedly injured by bullets fired by the police, including two with wounds to the head. Police reportedly beat a human rights monitor from the Institute for Human Rights Study and Advocacy who was trying to photograph the police attack on the crowd. Outnumbered by the crowd, the police retreated temporarily until reinforcements arrived and then forced an end to the ceremony. Police arrested Filep Karma at the site of the ceremony, and reportedly beat and stomped on him during transport to the police station. A group of about 20 people were later arrested at the police station when they went to protest Mr. Karma’s arrest, but all were subsequently released, except for Yusak Pakage. Mr. Karma and Mr. Pakage were later charged with rebellion for their role in leading and organizing the flag-raising event. In May 2005, a court sentenced Filep Karma to 15 years in prison and Yusak Pakage to 10 years on charges of treason for having “betrayed” Indonesia by flying the outlawed Papua flag. -

Papua: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°53 Jakarta/Brussels, 5 September 2006 Papua: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions I. OVERVIEW by the plummeting of Indonesian-Australian relations in early 2006 over Australia’s decision to grant temporary asylum to a group of Papuan political activists. No part of Indonesia generates as much distorted reporting as Papua, the western half of New Guinea that has been This briefing will examine several questions that lie home to an independence movement since the 1960s. behind the distortions: Who governs Papua and how? Are TNI numbers Some sources, mostly outside Indonesia, paint a picture increasing, and if so, why? of a closed killing field where the Indonesian army, backed by militia forces, perpetrates genocide against a What substance is there to the claim of historical defenceless people struggling for freedom. A variant has injustice in Papua’s integration into Indonesia? the army and multinational companies joining forces to How strong is the independence movement in despoil Papua and rob it of its own resources. Proponents Papua? Who supports it? of this view point to restrictions on media access, increasing troop strength in Papua of the Indonesian armed What substance is there to allegations of genocide? forces (TNI), payments to the TNI from the giant U.S. Are there Muslim militias in Papua? And a process copper and gold mining company, Freeport, and reports of Islamicisation? by human rights organisations as supporting evidence for their views. How much of Papua is off-limits to outsiders? Why the restrictions? Others, mostly inside Indonesia, portray Papua as What can the international community do? the target of machinations by Western interests, bent on bringing about an East Timor-style international intervention that will further divide and weaken the II. -

Preliminary Report Consists of Factual Information Collected Until the Preliminary Report Published

PRELIMINARY KNKT.16.09.27.04 Aircraft Accident Investigation Report PT. Trigana Air Service Boeing 737-300F; PK-YSY Wamena Airport, Papua Republic of Indonesia 13 September 2016 This preliminary investigation report was produced by the Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi (KNKT), Transportation Building, 3rd Floor, Jalan Medan Merdeka Timur No. 5 Jakarta 10110, Indonesia. The report is based upon the initial investigation carried out by the KNKT in accordance with Annex 13 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation Organization, the Indonesian Aviation Act (UU No. 1/2009) and Government Regulation (PP No. 62/2013). The preliminary report consists of factual information collected until the preliminary report published. This report will not include analysis and conclusion. Readers are advised that the KNKT investigates for the sole purpose of enhancing aviation safety. Consequently, the KNKT reports are confined to matters of safety significance and may be misleading if used for any other purpose. As the KNKT believes that safety information is of greatest value if it is passed on for the use of others, readers are encouraged to copy or reprint for further distribution, acknowledging the KNKT as the source. When the KNKT makes recommendations as a result of its investigations or research, safety is its primary consideration. However, the KNKT fully recognizes that the implementation of recommendations arising from its investigations will in some cases incur a cost to the industry. Readers should note that the information in KNKT reports and recommendations is provided to promote aviation safety. In no case is it intended to imply blame or liability. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................