General Assembly Distr.: General 9 March 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi

International Center for Transitional Justice The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi June 2012 Cover: A Papuan victim shows diary entries from 1969, when he was detained and transported to Java before the Act of Free Choice. ICTJ International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua Before and After Reformasi www.ictj.org iii International Center The Past That Has Not Passed: Human Rights Violations in Papua for Transitional Justice Before and After Reformasi Acknowledgements The International Center for Transitional Justice and (ICTJ) and the Institute of Human Rights Studies and Advocacy (ELSHAM) acknowledges the contributions of Matthew Easton, Zandra Mambrasar, Ferry Marisan, Joost Willem Mirino, Dominggas Nari, Daniel Radongkir, Aiesh Rumbekwan, Mathius Rumbrapuk, Sem Rumbrar, Andy Tagihuma, and Galuh Wandita in preparing this paper. Editorial support was also provided by Tony Francis, Atikah Nuraini, Nancy Sunarno, Dodi Yuniar, Dewi Yuri, and Sri Lestari Wahyuningroem. Research for this document were supported by Canada Fund. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of ICTJ and ELSHAM and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. About the International Center for Transitional Justice ICTJ works to assist societies in regaining humanity in the wake of massive human rights abuses. We provide expert technical advice, policy analysis, and comparative research on transitional justice approaches, including criminal prosecutions, reparations initiatives, truth seeking and memory, and institutional reform. -

Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA

Filep Karma adalah pemimpin paling berani di Papua Barat. Dia lawan kekerasan dengan taktik non-kekerasan macam Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King dan Nelson Mandela. Eben Kirksey, antropolog, menulis buku “Freedom in Entangled Worlds: West Papua and the Architecture of Global Power” Filep Karma’s steadfast resistance is an inspiration to all those struggling for human rights and justice for West Papua and elsewhere. John M. Miller, koordinator East Timor and Indonesia Action Network di New York Filep Karma is known to many in New Zealand. He is an icon of commit- ment to justice and freedom. Maire Leadbeater dari Auckland Aotearoa menulis buku “Negligent Neighbour: New Zealand’s Complicity in the Invasion and Occupation of Timor-Leste” Seakan Kitorang Setengah BinAtang RASIALISME INDONESIA DI TANAH PAPUA FILEP KARMA Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua ©Deiyai Cetakan Pertama, November 2014 Interviewer Basilius Triharyanto Firdaus Mubarik Ruth Ogetay Nona Elisabeth Editor Lovina Soenmi Tata Letak dan Disain Henry Adrian Foto Cover Depan nobodycorp.org Foto Cover Belakang Eben Kirksey Karma, Filep Seakan Kitorang Setengah Binatang Rasialisme Indonesia di Tanah Papua Deiyai, Jayapura, 2014 xvi + 137 hlm; 14,5 x 21,5 cm ISBN 978-602-17071-4-2 vi DAFTAR ISI ix Pengantar: Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua oleh Jim Elmslie 1 Masa Kecil di Wamena dan Jayapura 13 Biak Berdarah 25 Nasionalisme Papua 45 Perjalanan dalam Gambar 65 Dari Penjara ke Penjara 81 Kritik Langkah Perjuangan 101 Lampiran: Keputusan UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention oleh Freedom Now 129 Epilog: Menemui Filep Karma oleh Anugerah Perkasa vii viii PENGANTAR ix SEAKAN KITORANG SETENGAH BINATANG Perjuangan Seorang Pegawai Negeri di Papua FILEP KARMA, kelahiran 1959, menjalani hidupnya dalam bayang- bayang militer Indonesia. -

Papua JOHN BRAITHWAITE, MICHAEL COOKSON, VALERIE BRAITHWAITE and LEAH DUNN1

2. Papua JOHN BRAITHWAITE, MICHAEL COOKSON, VALERIE BRAITHWAITE AND LEAH DUNN1 Papua is interpreted here as a case with both high risks of escalation to more serious conflict and prospects for harnessing a ‘Papua Land of Peace’ campaign led by the churches. The interaction between the politics of the Freeport mine and the politics of military domination of Papua, and military enrichment through Papua, are crucial to understanding this conflict. Replacing the top- down dynamics of military-political domination with a genuine bottom-up dynamism of village leadership and development is seen as holding the key to realising a Papua that is a ‘land of peace’ (see Widjojo et al. 2008). Papuans have less access to legitimate economic opportunities than any group in Indonesia and have experienced more violence and torture since the late 1960s in projects of the military to block their political aspirations than any other group in Indonesia today. Institutions established with the intent of listening to Papuan voices have in practice been deaf to those voices. Calls for truth and reconciliation are among the pleas that have fallen on deaf ears, which is an acute problem when so many Papuans see Indonesian policy in Papua as genocide. Anomie in the sense of withdrawal of commitment to the Indonesian normative order by citizens, and in the sense of gaming that order by the military, is entrenched in Papua. Background to the conflict Troubled jewels of cultural and biological diversity The island of New Guinea and the smaller islands along its coast are home to nearly 1000 languages (267 on the Indonesian side) and one-sixth of the world’s ethnicities (Ruth-Hefferbower 2002:228). -

Suharto Dies Without Being Brought to Justice

Tapol bulletin no, 188/189, March 2008 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (2008) Tapol bulletin no, 188/189, March 2008. Tapol bulletin (188). pp. 1-36. ISSN 1356-1154 The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25927/ Bulletin no.188/189 March 2008 ISSN 1356-1154 Promoting human rights, peace and democracy in Indonesia Suharto dies without being brought to justice The following statement was issued by TAPOL after the death of Suharto on 27 January 2008: It is hard to exaggerate the damage inflicted on political rights, the rule of law ceased to function and Indonesia by the form'er dictator Suharto, who died today, gross human rights violations occurred without end. during the 33 years when he ruled the country with a rod After Suharto was forced to resign when mass of iron until his downfall in May 1998. demonstrations swept Indonesia in 1998 in response to Suharto rose to power on a wave of massacres that the financial crisis engulfing the country, the political killed up to one million people, one of the twentieth constraints on the population were lifted. But the century's worst crimes against humanity for which no one damaging impact of military impunity and the lack of has been brought to justice. Tens of thousands more were incarcerated and held for more than a decade without charge or trial. 13,000 men were banished to the remote island of Buru, out of reach of their families and subject to Contents a harsh physical environment and unremitting hard labour, which caused hundreds of deaths. -

"Don't Bother, Just Let Him Die"

"DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE" KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International Indonesia 2018 Cover photo: A Papuan woman mourns the victim of shootings in Paniai Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a © Amnesty International Indonesia/Bagus Septa Pratama Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons license. First published in 2018 by Amnesty International Indonesia HDI Hive Menteng 3rd Floor, Probolinggo 18 Jakarta Pusat 10350 Index: ASA 21/8198/2018 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International Indonesia amnesty.org – amnestyindonesia.org "DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE": KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA "DON'T BOTHER, JUST LET HIM DIE": KILLING WITH IMPUNITY IN PAPUA 3 Amnesty International Indonesia CONTENTS GLOSSARY 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 2. BACKGROUND 13 3. INDONESIA’S OBLIGATION UNDER INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AND IN NATIONAL LEGISLATION 23 4. -

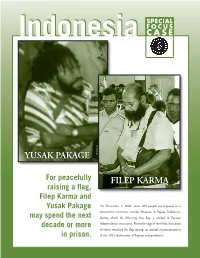

Yusak Pakage Filep Karma

SPECIAL FOCUS IndonesiaIndonesia CASE YUSAK PAKAGE ©ELSHAM For peacefully FILEP KARMA ©ELSHAM raising a flag, Filep Karma and On December 1, 2004, some 200 people participated in a Yusak Pakage nonviolent ceremony outside Abepura in Papua, Indonesia, may spend the next during which the Morning Star flag, a symbol of Papuan decade or more independence, was raised. From the edge of the fields, hundreds of others watched the flag-raising, an annual commemoration in prison. of the 1962 declaration of Papuan independence. Indonesian police advanced on the crowd, firing shots and beating people with batons. At least four people were reportedly injured by bullets fired by the police, including two with wounds to the head. Police reportedly beat a human rights monitor from the Institute for Human Rights Study and Advocacy who was trying to photograph the police attack on the crowd. Outnumbered by the crowd, the police retreated temporarily until reinforcements arrived and then forced an end to the ceremony. Police arrested Filep Karma at the site of the ceremony, and reportedly beat and stomped on him during transport to the police station. A group of about 20 people were later arrested at the police station when they went to protest Mr. Karma’s arrest, but all were subsequently released, except for Yusak Pakage. Mr. Karma and Mr. Pakage were later charged with rebellion for their role in leading and organizing the flag-raising event. In May 2005, a court sentenced Filep Karma to 15 years in prison and Yusak Pakage to 10 years on charges of treason for having “betrayed” Indonesia by flying the outlawed Papua flag. -

Papua: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°53 Jakarta/Brussels, 5 September 2006 Papua: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions I. OVERVIEW by the plummeting of Indonesian-Australian relations in early 2006 over Australia’s decision to grant temporary asylum to a group of Papuan political activists. No part of Indonesia generates as much distorted reporting as Papua, the western half of New Guinea that has been This briefing will examine several questions that lie home to an independence movement since the 1960s. behind the distortions: Who governs Papua and how? Are TNI numbers Some sources, mostly outside Indonesia, paint a picture increasing, and if so, why? of a closed killing field where the Indonesian army, backed by militia forces, perpetrates genocide against a What substance is there to the claim of historical defenceless people struggling for freedom. A variant has injustice in Papua’s integration into Indonesia? the army and multinational companies joining forces to How strong is the independence movement in despoil Papua and rob it of its own resources. Proponents Papua? Who supports it? of this view point to restrictions on media access, increasing troop strength in Papua of the Indonesian armed What substance is there to allegations of genocide? forces (TNI), payments to the TNI from the giant U.S. Are there Muslim militias in Papua? And a process copper and gold mining company, Freeport, and reports of Islamicisation? by human rights organisations as supporting evidence for their views. How much of Papua is off-limits to outsiders? Why the restrictions? Others, mostly inside Indonesia, portray Papua as What can the international community do? the target of machinations by Western interests, bent on bringing about an East Timor-style international intervention that will further divide and weaken the II. -

Indonesia's Political Prisoners

Indonesia H U M A N Prosecuting Political Aspiration R I G H T S Indonesia’s Political Prisoners WATCH Prosecuting Political Aspiration Indonesia’s Political Prisoners Copyright © 2010 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-642-X Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org June 2010 1-56432-642-X Prosecuting Political Aspiration Indonesia’s Political Prisoners Maps of Prisons with Political Prisoners in Indonesia ......................................................... 1 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Recommendations ........................................................................................................ 15 Methodology ................................................................................................................. 16 Political Prisoners from the Moluccas ................................................................................ 17 Background ................................................................................................................... 17 The 2007 Flag Unfurling and Its Violent Aftermath ........................................................ -

Amnesty International PAPUA Digest

A man in the Papua highlands © Private Amnesty International PAPUA DIGEST The people of Papua are subject to severe human rights violations at the hands of the Indonesian authorities. Their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are heavily curtailed. Many people are imprisoned simply for having taken part in non-violent demonstrations, or having expressed their opinions. The region of Papua is made up of two Indonesian With an area of 163,000 square miles of mountains, provinces – Papua and West Papua – which together tropical rainforest, agricultural land and marsh, Papua is form the western half of New Guinea, a large tropical rich in resources, including copper, oil, gold, timber and island north of Australia. The provincial capital of Papua fish. It is home to just over 3.5 million people, including province, Jayapura, is 200 miles south of the equator and some 250 indigenous groups. Indigenous Papuans are nearly 2,500 miles east of Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta. Melanesians and ethnically distinct from the majority of Indonesians, who are Malay. Christianity is the dominant Formerly a Dutch colony, the region was briefly transferred religion in Papua. Hundreds of thousands of people, to the United Nations Temporary Executive Authority principally Malay Muslims from other parts of Indonesia, in 1962 before being handed to Indonesia in 1963. It have settled in Papua. officially became the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya following a UN-supervised referendum in 1969, which is Despite its natural wealth, Papua remains one of the considered to have been fraudulent by most Papuans. Its least economically developed regions of Indonesia, with name changed yet again, to Papua, in 2002. -

Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-01 Flowers in the Wall: Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia Webster, David University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/106249 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca FLOWERS IN THE WALL Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Melanesia by David Webster ISBN 978-1-55238-955-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Filep Karma Is in Urgent Need of Medical Treatment

UA: 109/12 Index: ASA 21/017/2012 Indonesia Date: 19 April 2012 URGENT ACTION PRISONER'S MEDICAL TREATMENT PREVENTED Indonesian prisoner of conscience Filep Karma is in urgent need of medical treatment. He needs to travel to receive this treatment, but the prison authorities have refused to pay for his transport and medical costs. Filep Karma is serving a 15-year sentence at the Abepura prison in Papua province for raising a banned regional flag. Doctors at the Dok Dua hospital in nearby Jayapura conducted a medical examination last month and suspect a tumour of the colon. They have confirmed that he requires a colonoscopy and follow-up treatment. However the necessary equipment is not available in Papua province and they have referred him to the Cikini hospital in the capital, Jakarta. The Abepura prison authorities have given permission for Filep Karma to travel to Jakarta, but they have refused to cover the cost of his medical treatment and travel. By law, all medical costs for treatment of a prisoner at a hospital must be borne by the state (Regulation No. 32/1999 on Terms and Procedures on the Implementation of Prisoners’ Rights in Prisons). Filep Karma has suffered a number of medical problems in detention, including bronchopneumonia, excess fluid in the lungs and a urinary tract infection. In July 2010 he was sent to a hospital in Jakarta for prostate surgery and other care. In November 2011 he was transferred to the Dok Dua hospital in Papua for an operation after he experienced bleeding haemorrhoids, chronic diarrhoea and blood in his stool. -

West Papua Report March 2010

West Papua Report March 2010 This is the 70th in a series of monthly reports that focus on developments affecting Papuans. This series is produced by the non- profit West Papua Advocacy Team (WPAT) drawing on media accounts, other NGO assessments, and analysis and reporting from sources within West Papua. This report is co-published with the East Timor and Indonesia Action Network (ETAN) Back issues are posted online at http://etan.org/issues/wpapua/default.htm Questions regarding this report can be addressed to Edmund McWilliams at [email protected]. Summary The West Papua Advocacy Team urges President Obama to use his March visit to Indonesia to call on the Indonesian Government to implement fundamental changes in West Papua where human rights violations and impunity for security force crimes persist. Reporting from the central highlands in West Papua indicate an increased presence of security force and abusive and corrupt behavior of these forces. Papuans have peacefully demonstrated in large numbers to press demands for the release of political prisoners, respect for human rights, the investigation and prosecution of the killing of a peaceful demonstrator, and for demilitarization of West Papua. Papuans also have protested an Indonesian Government plan to seize vast tracts of land for "development" and displace many Papuans. The Indonesian government has failed to provide urgent health care for Filep Karma, a Papuan political prisoner. An Indonesian Minister has protested that Freeport McMoran, the giant U.S. mining operation, is operating illegally. Papuans have rejected plans by the Provincial government of West Java and the national government to send migrants to West Papua.