NSG Membership for India and Pakistan: Debating 'Critical' Aspects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charter of Independence: a Critical Study of Mujib's Six Point Programme

Ayyaz GullI CHARTER OF INDEPENDENCE: A CRITICAL STUDY OF MUJIB'S SIX POINT PROGRAMME Abstract This paper will try to explore the role of Bengali political leadership to transform the dream of separation of East Pakistan into reality. It will also provide a detailed and systematic study of Six Point Programme of Awami League which proved to be a 'charter of independence' and gave a comprehensive analysis of the basic demands of East Pakistanis and successfully combined public opinions in order to get mass support in the struggle for freedom from the West Pakistan. Moreover, this study will seek several waves of criticism regarding Six Point Programme by the state of Pakistan, political parties of West and East Pakistan, and even by the people within the Awami League. Key Words: Six Point Formula, Two Economy Thesis, Secessionist Movement, Economic Disparities, Conspiracy Theories The East Bengalis political elite played an important role in the separation of East Pakistan. It was economic exploitation which gave them an ample opportunity to win over popular support. They were conscious of these distinct geographical and cultural features, and they lost no occasion to project the differences between the two wings. They highlighted the points of ‘separateness’ in their speeches in the Constituent Assembly and the Provincial Assemblies. For instance, Abdul Mansur Ahmad, a prominent member from East Pakistan, observed in Constituent Assembly Pakistan is a unique country having two wings which are separated by a distance of more than a thousand miles…religion and common struggle are the only common factors… with the exception of these two things, all other factors, viz the language, the culture…practically everything is different. -

IWCSS 2020 Organizing and Program Committees

IWCSS 2020 Organizing and Program Committees General Chairs J. Christopher Westland, University of Illinois (Chicago), USA Hai Jiang, Arkansas State University, USA Aniello Castiglione, University of Naples Parthenope, Italy Program Chairs Valentina Emilia Balas, "Aurel Vlaicu" University of Arad, Romania Yang Xu, Hunan University, China Program Committee Md Atiqur Rahman Ahad, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh Saqib Ali, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan Flora Amato, University of "Naples Federico II", Italy Ranbir Singh Batth, Lovely Professional University, India Oana Geman, Stefan cel Mare University of Suceava, Romania Che-Lun Hung, Providence University, Taiwan Xing Gao, University of Memphis, USA Donghoon Kim, Arkansas State University, USA Gabor Kiss, Obuda University, Hungary Konstantinos Kolias, University of Idaho, USA Neeraj Kumar, Thapar Institute of Engineering and Technology, India Anyi Liu, Oakland University, USA Weizhi Meng, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark Fabio Narducci, University of Naples "Parthenope", Italy Anand Nayyar, Duytan University, Vietnam Reza Meimandi Parizi, Kennesaw State University, USA Emil Pricop, Petroleum - Gas University of Ploiesti, Romania Quan Qian, Shanghai University, China Vijender Kr. Solanki, CMR Institute of Technology, Hyderabad, India Zhiyuan Tan, Napier University, UK Bing Tang, Hunan University of Science and Technology, China Muhhamad Imran Tariq, Superior University Lahore, Pakistan Ning Wang, Rowan University, USA Haitao Xu, Arizona State University, USA Pengcheng You, Johns Hopkins University, USA Ji Zhang, University of Southern Queensland, Australia Philippe Fournier-Viger, Harbin Institute of Technology, China Hairong Lv, Tsinghua University, China Shuo Feng, McMaster University, Canada Venkatasamy Sureshkumar, PSG College of Technology, India Qiao Hu, Hunan University, China Tasmina Islam, University of Kent, UK lxi Xiaokang Wang, St. -

Men's Athlete Profiles 1 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON

Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games - Men's Athlete Profiles 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON (CMR) Date Of Birth : 09/05/1989 Place Of Birth : Yaoundé Height : 160cm Residence : Region du Centre 2018 – Indian Open Boxing Tournament (New Delhi, IND) 5th place – 49KG Lost to Amit Panghal (IND) 5:0 in the quarter-final; Won against Muhammad Fuad Bin Mohamed Redzuan (MAS) 5:0 in the first preliminary round 2017 – AFBC African Confederation Boxing Championships (Brazzaville, CGO) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Matias Hamunyela (NAM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Mohamed Yassine Touareg (ALG) 5:0 in the semi- final; Won against Said Bounkoult (MAR) 3:1 in the quarter-final 2016 – Rio 2016 Olympic Games (Rio de Janeiro, BRA) participant – 49KG Lost to Galal Yafai (ENG) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2016 – Nikolay Manger Memorial Tournament (Kherson, UKR) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Ievgen Ovsiannikov (UKR) 2:1 in the final 2016 – AIBA African Olympic Qualification Event (Yaoundé, CMR) 1st place – 49KG Won against Matias Hamunyela (NAM) WO in the final; Won against Peter Mungai Warui (KEN) 2:1 in the semi-final; Won against Zoheir Toudjine (ALG) 3:0 in the quarter-final; Won against David De Pina (CPV) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2015 – African Zone 3 Championships (Libreville, GAB) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the final 2014 – Dixiades Games (Yaounde, CMR) 3rd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the semi- final 2014 – Cameroon Regional Tournament 1st place – 49KG Won against Tchouta Bianda (CMR) -

News Letter Embassy of Pakistan Jakarta April - June 2015

NEWS LETTER EMBASSY OF PAKISTAN JAKARTA APRIL - JUNE 2015 Contents of the Issue Death of Indonesian Ambassador to Pakistan, Burhan Muhammad · Death of Indonesian and His Wife in Pakistan Helicopter Crash Ambassador to Pakistan Burhan Muhammad 1 · Asian-African Conference 2015 2 · Media Engagement 2 · Indonesia Participation in My Karachi Expo 2 Tributes paid to Ambassador Burhan Muhammad at · Indonesia-Pakistan Gedung Pancasila, Jakarta Bilateral Data 2 Indonesian ambassador to Pakistan President of Indonesia, Joko Widodo · Asian-African Business Burhan Muhammad died at the expressed deep sorrow on the passing Summit 2015 3 Singapore General Hospital on 19th of Indonesian Ambassador to May 2015, 11 days after the Pakistan, Burhan Muhammad. · Visit of NDU Delegates 3 Pakistani military helicopter he was The body was taken to the family · Pakistan Stall at AITIS 2015 3 travelling on crashed in the home where he was buried with full mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan, military honours. Pakistan High · Economic Activities 3 Pakistan on May 8. The accident Commissioner to Singapore H.E. · Obituary of Ambassador killed seven people on the spot, Tanveer Khaskheli and Pakistan including his wife Heri Listyawati Charge d’ Affairs to Indonesia, Syed Burhan Muhammad 4 and envoys from the Philippines and Zahid Raza, represented government · Activities at Norway. The envoys were part of a of Pakistan at the funeral. Pakistan Embassy, Jakarta 4 large group of foreign dignitaries Earlier, Minister of Defence being ferried to the inauguration of a Production, Mr. Rana Tanveer Cd'A / Counsellor ski resort chairlift in the town of Hussein brought the dead body of Syed Zahid Raza Naltar. -

Partition of Punjab: Sikhs and Lyallpur, Explores the Significance of Lyallpur in Partition of Punjab

THIS DISSERTATION IS BEING SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY ROLE OF MIGRANTS IN MAKING OF MODERN FAISALABAD 1947-1960 Submitted By: Muhammad Abrar Ahmad Ph. D. 2011-2016 Research Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Dean, Faculty of Arts & Humanities University of the Punjab Department of History & Pakistan Studies University of the Punjab, Lahore 2016 In the name of ALLAH, the creator of the universe the most beneficent, most merciful. DECLARATION I, hereby, declare that this Ph. D thesis titled “Role of Migrants in Making of Modern Faisalabad 1947-1960” is the result of my personal research and is not being submitted concurrently to any other University for any degree or whatsoever. Muhammad Abrar Ahmad Ph. D. Scholar I CERTIFICATE Certificate by Research Supervisor This is to certify that Muhammad Abrar Ahmad has completed the Dissertation entitled “Role of Migrants in Making of Modern Faisalabad 1947-1960” under my supervision. It fulfills the requirements necessary for submission of the dissertation for the Doctor of Philosophy in History. Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Dean, Faculty of Arts & Humanities, University of the Punjab, Lahore. Submitted Through Prof. Dr. Muhammad Iqbal Chawla Chairman, Department of History & Pakistan Studies, University of the Punjab, Lahore External Examiner II DEDICATED To My Loving Amma Gee (Late) who has been a constant source of warmth and inspiration III Acknowledgement First of all, I offer my bow of humility to Almighty Allah who opened my mind and enabled me to carry out this noble task of contributing few drops in ocean of knowledge. -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 07/17/2013 12:53:25 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 «JJ.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 06/30/2013 (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf 5975 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 315 Maple street Richardson TX, 75081 Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes Q No D (2) Citizenship Yes Q No Q (3) Occupation Yes • No D (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes Q No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No |x] - (3) Branch offices Yes D No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No D If no, please attach the required amendment. I The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy of the charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

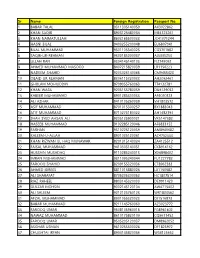

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No. 1 BABAR

Sr Name Foreign Registration Passport No. -

Organisational Matters Relating to the Postponed Tenth (2020) NPT Review Conference

Organisational matters relating to the postponed Tenth (2020) NPT Review Conference GLOBAL SECURITY REPORT Tariq Rauf February 2021 The European Leadership Network (ELN) is an independent, non-partisan, pan-European network of nearly 200 past, present and future European leaders working to provide practical real-world solutions to political and security challenges. About the author Tariq Rauf was Head of Verification and Security Policy Cooperation at the International Atomic Energy Agency; Alternate Head of the IAEA NPT Delegation 2002-2010; IAEA Liaison and Point-of-Contact for the Trilateral Initiative, the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement, the Fissile Material Control Treaty, the Nuclear Suppliers Group, the Zangger Committee, Committee UNSCR 1540, and the (UN) Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force (CTITF); and responsible for the IAEA Forum on Experience of Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones Relevant for the Middle East. He has attended all NPT meetings from 1987 to 2019 as an official delegate including as Non-Proliferation Expert with Canada’s NPT Delegation 1987-2000; and Senior Advisor to the 2014 NPT PrepCom Chair and to the Chair of Main Committee I at the 2015 review conference. Personal views are expressed here for purposes of discussion. Published by the European Leadership Network, February 2021 European Leadership Network (ELN) 8 St James’s Square London, UK, SE1Y 4JU @theELN europeanleadershipnetwork.org Published under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 © The ELN 2021 The opinions articulated in this report represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Leadership Network or any of its members. -

Las Coaliciones Promotoras Y Los Contextos Que

LAS COALICIONES PROMOTORAS Y LOS CONTEXTOS QUE LLEVARON AL AVANCE DEL PROYECTO ATÓMICO CAREM (CENTRAL ARGENTINA DE ELEMENTOS MODULARES) EN ARGENTINA ENTRE 1976 Y 2015 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Development Management and Policy By Francisco Paterson, B.A. Buenos Aires December 5, 2018 Copyright 2018 by Francisco Paterson All rights reserved ii ADVOCACY COALITIONS AND THE CONTEXTS THAT LED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF CAREM ATOMIC PROJECT (CENTRAL ARGENTINA DE ELEMENTOS MODULARES) IN ARGENTINA BETWEEN 1976 AND 2015 Francisco Paterson, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Diego Hurtado de Mendoza Ph. D. ABSTRACT While the way in which the State makes decisions regarding matters of public policy cannot be reduced to a simple universal explanation, it is, however, important to try to grasp why certain matters are of sufficient concern to be dealt with by the governmental apparatus. In an analysis of the more than 38-year history of the fully State-owned CAREM (Central Argentina de Elementos Modulares) nuclear power reactor, I use the advocacy coalition framework and the political contexts in which it advanced to examine the beliefs held by the actors that shaped the progress of the project throughout its chronology. Originally conceptualized in the 1970s as part of a military program for naval propulsion, the reactor was presented as a civilian project in 1984 and went through ups and downs in its development until the 2006 Argentinian Nuclear Plan from which it derives its budget today. -

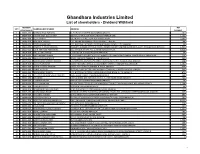

List of Shareholder-Dividend Withheld

Ghandhara Industries Limited List of shareholders - Dividend Withheld MEMBER NET SR # SHAREHOLDER'S NAME ADDRESS FOLIO PAR ID PAYABLE 1 00002-000 MISBAHUDDIN FAROOQI D-151 BLOCK-B NORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 461 2 00004-000 FARHAT AFZA BEGUM MST. 166 ABU BAKR BLOCK NEW GARDEN TOWN,LAHORE 1,302 3 00005-000 ALLAH RAKHA 135-MUMTAZ STREETGARHI SHAHOO,LAHORE. 3,293 4 00006-000 AKHTAR A. PERVEZ C/O. AMERICAN EXPRESS CO.87 THE MALL, LAHORE. 180 5 00008-000 DOST MUHAMMAD C/O. NATIONAL MOTORS LIMITEDHUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.KARACHI. 46 6 00010-000 JOSEPH F.P. MASCARENHAS MISQUITA GARDEN CATHOLIC COOP.HOUSING SOCIETY LIMITED BLOCK NO.A-3,OFF: RANDLE ROAD KARACHI. 1,544 7 00013-000 JOHN ANTHONY FERNANDES A-6, ANTHONIAN APT. NO. 1,ADAM ROAD,KARACHI. 5,004 8 00014-000 RIAZ UL HAQ HAMID C-103, BLOCK-XI, FEDERAL.B.AREAKARACHI. 69 9 00015-000 SAIED AHMAD SHAIKH C/O.COMMODORE (RETD) M. RAZI AHMED71/II, KHAYABAN-E-BAHRIA, PHASE-VD.H.A. KARACHI-46. 214 10 00016-000 GHULAM QAMAR KURD 292/8, AZIZABAD FEDERAL B. AREA,KARACHI. 129 11 00017-000 MUHAMMAD QAMAR HUSSAIN C/O.NATIONAL MOTORS LTD.HUB CHAUKI ROAD, S.I.T.E.,P.O.BOX-2706, KARACHI. 218 12 00018-000 AZMAT NAWAZISH AZMAT MOTORS LIMITED, SC-43,CHANDNI CHOWK, STADIUM ROAD,KARACHI. 1,585 13 00021-000 MIRZA HUSSAIN KASHANI HOUSE NO.R-1083/16,FEDERAL B. AREA, KARACHI 434 14 00023-000 RAHAT HUSSAIN PLOT NO.R-483, SECTOR 14-B,SHADMAN TOWN NO.2, NORTH KARACHI,KARACHI. -

Isolation and Molecular Characterization

Isolation and molecular characterization of the indigenous Staphylococcus aureus strain K1 with the ability to reduce hexavalent chromium for its application in bioremediation of metal-contaminated sites Muhammad Tariq1, Muhammad Waseem1, Muhammad Hidayat Rasool1, Muhammad Asif Zahoor1 and Irshad Hussain2 1 Department of Microbiology, Government College University, Faisalabad, Punjab, Pakistan 2 Department of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, The Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan ABSTRACT Background. Urbanization and industrialization are the main anthropogenic activities that are adding toxic heavy metals to the environment. Among these, chromium (in hexavalent: Cr+6 and/or trivalent Cr+3) is being released abundantly in wastewater due to its uses in different industrial processes. It becomes highly mutagenic and carcinogenic once it enters the cell through sulfate uptake pathways after interacting with cellular proteins and nucleic acids. However, Cr+6 can be bio-converted into more stable, less toxic and insoluble trivalent chromium using microbes. Hence in this study, we have made efforts to utilize chromium tolerant bacteria for bio-reduction of Cr+6 to Cr+3. Methods. Bacterial isolate, K1, from metal contaminated industrial effluent from Kala Shah Kaku-Lahore Pakistan, which tolerated up to 22 mM of Cr6+ was evaluated for chromate reduction. It was further characterized biochemically and molecularly Submitted 29 April 2019 R Accepted 22 August 2019 by VITEK 2 system and 16S rRNA gene sequencing respectively. Other factors Published 11 October 2019 affecting the reduction of chromium such as initial chromate ion concentration, pH, Corresponding author temperature, contact-time were also investigated. The role of cellular surface in sorption 6+ Muhammad Waseem, of Cr ion was analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy. -

Nuclear Reactors Made in Patagonia Argentine Firm Invap, Leader in the Nuclear Technology Field in Latin America, Makes Its Mark in the Aerospace Sector

Nuclear Reactors made in Patagonia Argentine firm Invap, leader in the nuclear technology field in Latin America, makes its mark in the aerospace sector FRANCISCA RISATTI Buenos Aires 9 OCT 2016 In 2000, when Australia had to decide who would build its only nuclear research reactor to replace a British model, an Argentine public-funded company, which at the time had 350 employees, fought off competition from industry heavyweights such as the French firm Technicatome (‘Areva’ since 2006) and the German firm Siemens. Invap built the reactor at its Patagonian hub in San Carlos de Bariloche. The achievement, marking the firm’s first export to a developed country, set it firmly among the big league for service providers of nuclear technology for peaceful means. Today, on the verge of celebrating its 40th anniversary, and following a move towards greater diversification, the company has proved Argentina to be the only Latin American country capable of designing, building and operating its own satellites. The Argentine Ambassador to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as well as its former assistant director-general, Rafael Grossi, has said that the company occupies a “leading position” in the research reactor industry. “Invap’s great asset is its ability to produce what the client needs, rather than selling them something they already make. Invap sees the problem and the technological requirements and then considers and designs the solution”, Grossi stated. “When we won the bid for the Australia project, the company was turning over around 30 million dollars per year. Over the last 15 years, this figure has increased six-fold and today we have a turnover of around 200 million dollars”, said Héctor Otheguy, the company’s CEO, at Invap’s headquarters in Buenos Aires.