REMOTE SENSING of PLANETARY SURFACES Final Report, NAG5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanic History of the Imbrium Basin: a Close-Up View from the Lunar Rover Yutu

Volcanic history of the Imbrium basin: A close-up view from the lunar rover Yutu Jinhai Zhanga, Wei Yanga, Sen Hua, Yangting Lina,1, Guangyou Fangb, Chunlai Lic, Wenxi Pengd, Sanyuan Zhue, Zhiping Hef, Bin Zhoub, Hongyu Ling, Jianfeng Yangh, Enhai Liui, Yuchen Xua, Jianyu Wangf, Zhenxing Yaoa, Yongliao Zouc, Jun Yanc, and Ziyuan Ouyangj aKey Laboratory of Earth and Planetary Physics, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China; bInstitute of Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; cNational Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100012, China; dInstitute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; eKey Laboratory of Mineralogy and Metallogeny, Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China; fKey Laboratory of Space Active Opto-Electronics Technology, Shanghai Institute of Technical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200083, China; gThe Fifth Laboratory, Beijing Institute of Space Mechanics & Electricity, Beijing 100076, China; hXi’an Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710119, China; iInstitute of Optics and Electronics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610209, China; and jInstitute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Science, Guiyang 550002, China Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved March 24, 2015 (received for review February 13, 2015) We report the surface exploration by the lunar rover Yutu that flows in Mare Imbrium was obtained only by remote sensing from landed on the young lava flow in the northeastern part of the orbit. On December 14, 2013, Chang’e-3 successfully landed on the Mare Imbrium, which is the largest basin on the nearside of the young and high-Ti lava flow in the northeastern Mare Imbrium, Moon and is filled with several basalt units estimated to date from about 10 km south from the old low-Ti basalt unit (Fig. -

A Summary of the Unified Lunar Control Network 2005 and Lunar Topographic Model B. A. Archinal, M. R. Rosiek, R. L. Kirk, and B

A Summary of the Unified Lunar Control Network 2005 and Lunar Topographic Model B. A. Archinal, M. R. Rosiek, R. L. Kirk, and B. L. Redding U. S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA, [email protected] Introduction: We have completed a new general unified lunar control network and lunar topographic model based on Clementine images. This photogrammetric network solution is the largest planetary control network ever completed. It includes the determination of the 3-D positions of 272,931 points on the lunar surface and the correction of the camera angles for 43,866 Clementine images, using 546,126 tie point measurements. The solution RMS is 20 µm (= 0.9 pixels) in the image plane, with the largest residual of 6.4 pixels. We are now documenting our solution [1] and plan to release the solution results soon [2]. Previous Networks: In recent years there have been two generally accepted lunar control networks. These are the Unified Lunar Control Network (ULCN) and the Clementine Lunar Control Network (CLCN), both derived by M. Davies and T. Colvin at RAND. The original ULCN was described in the last major publication about a lunar control network [3]. Images for this network are from the Apollo, Mariner 10, and Galileo missions, and Earth-based photographs. The CLCN was derived from Clementine images and measurements on Clementine 750-nm images. The purpose of this network was to determine the geometry for the Clementine Base Map [4]. The geometry of that mosaic was used to produce the Clementine UVVIS digital image model [5] and the Near-Infrared Global Multispectral Map of the Moon from Clementine [6]. -

Modeling and Adjustment of THEMIS IR Line Scanner Camera Image Measurements

Modeling and Adjustment of THEMIS IR Line Scanner Camera Image Measurements by Brent Archinal USGS Astrogeology Team 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 [email protected] As of 2004 December 9 Version 1.0 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. General 1.2. Conventions 2. Observations Equations and Their Partials 2.1. Line Scanner Camera Specific Modeling 2.2. Partials for New Parameters 2.2.1. Orientation Partials 2.2.2. Spatial Partials 2.2.3. Partials of the observations with respect to the parameters 2.2.4. Parameter Weighting 3. Adjustment Model 4. Implementation 4.1. Input/Output Changes 4.1.1. Image Measurements 4.1.2. SPICE Data 4.1.3. Program Control (Parameters) Information 4.2. Computational Changes 4.2.1. Generation of A priori Information 4.2.2. Partial derivatives 4.2.3. Solution Output 5. Testing and Near Term Work 6. Future Work Acknowledgements References Useful web sites Appendix I - Partial Transcription of Colvin (1992) Documentation Appendix II - HiRISE Sensor Model Information 1. Introduction 1.1 General The overall problem we’re solving is that we want to be able to set up the relationships between the coordinates of arbitrary physical points in space (e.g. ground points) and their coordinates on line scanner (or “pushbroom”) camera images. We then want to do a least squares solution in order to come up with consistent camera orientation and position information that represents these relationships accurately. For now, supported by funding from the NASA Critical Data Products initiative (for 2003 September to 2005 August), we will concentrate on handling the THEMIS IR camera system (Christensen et al., 2003). -

Space Sector Brochure

SPACE SPACE REVOLUTIONIZING THE WAY TO SPACE SPACECRAFT TECHNOLOGIES PROPULSION Moog provides components and subsystems for cold gas, chemical, and electric Moog is a proven leader in components, subsystems, and systems propulsion and designs, develops, and manufactures complete chemical propulsion for spacecraft of all sizes, from smallsats to GEO spacecraft. systems, including tanks, to accelerate the spacecraft for orbit-insertion, station Moog has been successfully providing spacecraft controls, in- keeping, or attitude control. Moog makes thrusters from <1N to 500N to support the space propulsion, and major subsystems for science, military, propulsion requirements for small to large spacecraft. and commercial operations for more than 60 years. AVIONICS Moog is a proven provider of high performance and reliable space-rated avionics hardware and software for command and data handling, power distribution, payload processing, memory, GPS receivers, motor controllers, and onboard computing. POWER SYSTEMS Moog leverages its proven spacecraft avionics and high-power control systems to supply hardware for telemetry, as well as solar array and battery power management and switching. Applications include bus line power to valves, motors, torque rods, and other end effectors. Moog has developed products for Power Management and Distribution (PMAD) Systems, such as high power DC converters, switching, and power stabilization. MECHANISMS Moog has produced spacecraft motion control products for more than 50 years, dating back to the historic Apollo and Pioneer programs. Today, we offer rotary, linear, and specialized mechanisms for spacecraft motion control needs. Moog is a world-class manufacturer of solar array drives, propulsion positioning gimbals, electric propulsion gimbals, antenna positioner mechanisms, docking and release mechanisms, and specialty payload positioners. -

LUNAR REGOLITH PROPERTIES CONSTRAINED by LRO DIVINER and CHANG'e 2 MICROWAVE RADIOMETER DATA. J. Feng1, M. A. Siegler1, P. O

50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2132) 3176.pdf LUNAR REGOLITH PROPERTIES CONSTRAINED BY LRO DIVINER AND CHANG’E 2 MICROWAVE RADIOMETER DATA. J. Feng1, M. A. Siegler1, P. O. Hayne2, D. T. Blewett3, 1Planetary Sci- ence Institute (1700 East Fort Lowell, Suite 106 Tucson, AZ 85719-2395, [email protected]), 2University of Colorado, Boulder. 3Johns Hopkins Univ. Applied Physics Lab, Maryland. Introduction: The geophysical properties of the sults of the thermal model (which includes layer num- lunar regolith have been well-studied, but many uncer- bers, layer thickness, temperature profile and density tainties remain about their in-situ nature. Diviner Lunar profile) are input parameters for the microwave model. Radiometer Experiment onboard LRO [1] is an instru- In contrast to [2, 3], we update the thermal parame- ment measuring the surface bolometric temperature of ters to match the surface temperature at noon in the the regolith. It has been systematically mapping the equatorial region and diurnal temperature variation in Moon since July 5, 2009 at solar and infrared wave- high latitude (Fig. 1). The best fit of the data show that lengths covering a full range of latitudes, longitudes, for most highlands the regolith has a bond albedo of local times and seasons. The Microwave Radiometer 0.09 at normal solar incidence and bond albedo at arbi- (MRM) carried by Chang’e 2 (CE-2) was used to de- trary solar incidence θ is represented by A=0.09 rive the brightness temperature of the moon in frequen- +0.04×(4θ/π)3+0.05×(2θ/π)8. -

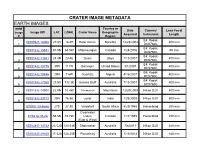

CRATER IMAGE METADATA EARTH IMAGES Country Or BMM Date Camera/ Lens Focal Image Image ID# LAT

CRATER IMAGE METADATA EARTH IMAGES Country or BMM Date Camera/ Lens Focal Image Image ID# LAT. LONG. Crater Name Geographic Acquired Instrument Length # Region E4: Kodak ISS006-E-16068 27.8S 16.4E Roter Kamm Namibia 12/28/2002 400 mm 1 DCS760C E4: Kodak ISS012-E-15881 51.5N 68.5W Manicouagan Canada 1/24/2006 50 mm 2 DCS760C E4: Kodak ISS014-E-11841 24.4N 24.4E Oasis Libya 1/13/2007 400 mm 3 DCS760C E4: Kodak ISS014-E-15775 35N 111W Barringer United States 3/1/2007 400 mm 4 DCS760C E4: Kodak ISS014-E-19496 29N 7.6W Ouarkziz Algeria 4/16/2007 800 mm 5 DCS760C E4: Kodak ISS015-E-17360 23.9S 132.3E Gosses Bluff Australia 7/13/2007 400 mm 6 DCS760C ISS018-E-14908 22.9N 10.4W Tenoumer Mauritania 12/20/2008 Nikon D2X 800 mm 7 ISS018-E-23713 20N 76.5E Lonar India 1/28/2009 Nikon D2X 800 mm 8 STS51I-33-56AA 27S 27.3E Vredefort South Africa 8/29/1985 Hasselblad 250 mm Clearwater STS61A-35-86 56.5N 74.7W Lakes Canada 11/1/1985 Hasselblad 250 mm (East & West) ISS028-E-14782 25.52S 120.53E Shoemaker Australia 7/6/2011 Nikon D2X 200 mm ISS034-E-29105 17.32S 128.25E Piccaninny Australia 1/15/2013 Nikon D2X 180 mm CRATER IMAGE METADATA MARS IMAGES BMM Geographic *Date or Camera/ Image Image ID# LAT. LONG. Crater Name Approx. YR Mission Name Region Instrument # Acquired PIA14290 5.4S 137.8E Gale Aeolis Mensae 2000's THEMIS IR Odyssey THEMIS IR Aeolis 14.5S 175.4E Gusev 2000's THEMIS IR Odyssey MOSAIC Quadrangle Mars Orbiter Colorized MOLA 42S 67E Hellas Basin Hellas Planitia 2000's Laser Altimeter Global Surveyor (MOLA) Viking Orbiter Margaritifer Visual -

Impact Craters) Into the Subsurface

SUBSURFACE MINERAL HETEROGENEITY IN THE MARTIAN CRUST AS SEEN BY THE THERMAL EMISSION IMAGING SYSTEM (THEMIS): VIEWS FROM NATURAL “WINDOWS” (IMPACT CRATERS) INTO THE SUBSURFACE. L. L. Tornabene1 , J. E. Moersch1, H. Y. McSween Jr.1, J. A. Piatek1 and P. R. Christensen2; 1Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996-1410, 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287–6305, USA. Introduction and Background: Impact craters have been effectively used as a “natural drill” into the crust of the moon, the Earth and on Mars, giving us a glimpse of the mineral and lithologic compositions that are otherwise not exposed or present on surfaces. A lunar study by Tomp- kins and Pieters [1] has demonstrated that Lunar Clementine data could be used to show that numerous craters on the Moon excavated distinct compositions within both the cen- tral uplift and craters walls/terraces of several complex cra- ters with respect to the surrounding lunar surface composi- tion. Later, Tornabene et al [2] demonstrated how Haughton impact structure was an excellent terrestrial analog for dem- onstrating the utility of using craters for studying both near- subsurface and the shallow crust of Mars. Using ASTER Thermal infrared (TIR) data, as an analog for THEMIS TIR, three subsurface units were distinguished within the structure as units that were excavated and uplifted by the impact event. These units, if not for the regional tilt and erosion, would otherwise not be presently exposed if not for the Haughton event. Meanwhile, recent studies on Mars by the Opportunity rover [3] revealed our first clear view of out- cropping bedrock of sedimentary layers within the walls of Eagle and Endurance craters. -

The Clementine Mission —

The Clementine mission – A 10-year perspective Trevor C Sorensen1,∗ and Paul D Spudis2 1University of Kansas, Lawrence KS, USA. 2Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel MD, USA. ∗e-mail: [email protected] Clementine was a technology demonstration mission jointly sponsored by the Department of Defense (DOD) and NASA that was launched on January 25th, 1994. Its principal objective was to use the Moon, a near-Earth asteroid, and the spacecraft’s Interstage Adapter as targets to demon- strate lightweight sensor performance and several innovative spacecraft systems and technologies. The design, development, and operation of the Clementine spacecraft and ground system was per- formed by the Naval Research Laboratory. For over two months Clementine mapped the Moon, producing the first multispectral global digital map of the Moon, the first global topographic map, and contributing several other important scientific discoveries, including the possibility of ice at the lunar South Pole. New experiments or schedule modifications were made with minimal constraints, maximizing science return, thus creating a new paradigm for mission operations. Clementine was the first mission known to conduct an in-flight autonomous operations experiment. After leaving the Moon, Clementine suffered an onboard failure that caused cancellation of the asteroid ren- dezvous. Despite this setback, NASA and the DOD applied the lessons learned from the Clemen- tine mission to later missions. Clementine set the standard against which new small spacecraft missions are commonly measured. -

Titan Explorer: the Next Step in the Exploration of a Mysterious World

Outer Planets Assessment Group (OPAG) 6-7 October 2005 Arlington, VA Titan Explorer: The Next Step in the Exploration of a Mysterious World Presentation based on the Final Report for NASA Vision Mission Study per NRA-03-OSS-01 (Submitted on 6/10/2005) Presented by: William Edwards, NASA Langley Research Center [email protected] Principal Investigator: Dr. Joel S. Levine, NASA Langley Research Center Study Lead: Henry S. Wright, NASA Langley Research Center Content - Agenda Titan Explorer • Goal • Science Questions • Science Payload • Data Collection Strategy • Titan Environment • Platform Comparison • Baseline Description - Airship – Configuration – Deployment – Subsystems – Operations • Conclusions Goals of the “Vision Mission” Titan Explorer • The first goal is to sharpen understanding of a subset of possible future missions for scientific and programmatic planning. These vision missions represent approaches to extending the current and near term flight programs to future, more advanced capabilities. • A second and equally important goal for improving our understanding of implementation of long term objectives is to support integration of long range Agency-wide planning. (i. e., use of astronauts, nuclear power, and other “high-dollar” technologies). Titan Explorer Science Questions Titan Explorer • What is the chemical composition of the atmosphere, including the trace gases? • What is the isotopic ratio of the gases in the atmosphere? • What pre-biological chemistry is occurring in the atmosphere/surface of Titan today and -

Clementine Observations of the Zodiacal Light and the Dust Content of the Inner Solar System

Clementine Observations of the Zodiacal Light and the Dust Content of the Inner Solar System Joseph M. Hahn Saint Mary’s University Institute for Computational Astrophysics February 13, 2004 with Herb Zook (NASA/JSC), Bonnie Cooper (OSS), Sunny Sunkara (LPI) 1 What is the Zodiacal Light? The zodiacal light (ZL) is sunlight that is scattered and/or reradiated by interplanetary dust. The inner ZL is observed towards the sun, usually at optical wavelengths. The outer ZL is observed away from the sun, usually at infrared wavelengths. photo by Marco Fulle. 2 Why Study Interplanetary Dust? “Someone unfamiliar with astrophysical problems would certainly consider the study of interplanetary dust as an exercise of pure academic interest and may even smile at the fact that much theoretical machinery is devoted to tiny dust grains” Philippe Lamy, 1975, Ph.D. thesis. 3 Why Study Interplanetary Dust? • Dust are samples of small bodies that formed in remote niches throughout the solar system, and they place constraints on conditions in the solar nebula during the planet–forming epoch. – dust from asteroids tell us of solar nebula conditions at r ∼ 3 AU – dust from long–period Oort Cloud comets tell us of nebula conditions at 5 . r . 30 AU – dust from short–period Jupiter–Family comets tell us of conditions in the Kuiper Belt at r & 30 AU • IF the information carried by dust samples (collected by U2 aircraft, Stardust, spacecraft dust collection experiments, etc.) are indeed decipherable, then their mineralogy will inform us of nebula conditions and its history over 3 . r . 30 AU. • However interpreting this dust requires understanding their sources (asteroid & comets), their spatial distributions, transport mechanisms, and sampling biases (e.g., certain sources may be more effective at delivering dust to your detector than other sources). -

3 Space Probes Critical Thinking

Name Class Date CHAPTER 22 Exploring Space SECTION 3 Space Probes BEFORE YOU READ After you read this section, you should be able to answer these questions: • Why do we use space probes to visit other planets? • What kinds of information can space probes gather? What Are Space Probes? What does the surface of Mars look like? Does life STUDY TIP exist anywhere else in the solar system? To answer ques- Summarize Make a timeline tions like these, scientists send space probes through showing when the space probes in this section were the solar system. A space probe is a vehicle that carries launched. On the timeline, scientific instruments into outer space, but has no people describe the destination of on board. Space probes visit planets or other bodies in each probe. space. They can complete missions that would be too dangerous or expensive for humans to carry out. LUNA AND CLEMENTINE Luna 1, the first space probe, was launched by the Soviet Union in 1959. It flew past the moon. In 1966, Luna 9 made the first soft landing on the moon’s surface. In all, space probes from the United States and the Soviet Union have completed more than 30 lunar missions. In 1994, the United States probe Clementine Critical Thinking discovered that craters on the moon may contain water. 1. Infer Why would frozen The water may have been left from comet impacts. In water on the moon be useful 1998, the Lunar Prospector confirmed that frozen water for a human colony there? exists on the moon. -

Near Earth Object (NEO) Mitigation Options Using Exploration Technologies

Near Earth Object (NEO) Mitigation Options Using Exploration Technologies Robert B. Adams1, Jonathan W. Campbell2, Randall C. Hopkins3 and W. Scott Smith4 National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Marshall Space Flight Center, MSFC, AL, 35812 William Arnold5 Jacob Sverdrup, Huntsville, AL 35812 Mike Baysinger6 and Tracie Crane7 Qualis Corporation, Huntsville, AL 35805 Pete Capizzo8 and Steven Sutherlin9 Raytheon Corporation, Huntsville, AL 35806 John Dankanich10 and Gordon Woodcock11 Gray Research Inc., Huntsville, AL 35806 George Edlin12 and Johnny Rushing13 Alpha Technology, Inc., Huntsville, AL 35801 Leo Fabisinski14, David Jones15, Steve McKamey16 and Scott Thomas17 International Space Systems, Inc., Huntsville, AL 35816 Claudio Maccone18 Member of the International Academy of Astronautics, Torino, Turin, Italy Greg Matloff19 New York City College of Technology, Brooklyn, NY, 11201 John Remo20 Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 1 Advanced Propulsion Technologist, EI63/Advanced Concepts, Senior Member AIAA. 2 Space Systems Engineer/Scientist, EV13/Space Environments, Associate Fellow AIAA. 3 Aerospace Engineer (Vehicle Design and Mission Analysis), EI63/Advanced Concepts. 4 Optical Physics, VP63/Optics. 5 Senior Principal Engineer, VP63/Optics. 6 Design Engineer,EI63/Advanced Concepts, 5000 Bradford Drive, Suite 3B. 7 Engineer, EI63/Advanced Concepts, 5000 Bradford Drive, Suite 3B. 8 Electrical and Avionics System Engineer, EI63/Advanced Concepts, 401 Jan Davis Drive. 9 Principal Multi-Discipline Engineer, ER23/Spacecraft Propulsion Systems, 401 Jan Davis Drive. 10 Aerospace Engineer, 655 Discovery Drive, Suite 300, Member AIAA. 11 Senior Engineer, 655 Discovery Drive, Suite 300, Associate Fellow AIAA. 12 Chief Scientist, Nuclear and Directed Energy Concepts, 3322 South Memorial Parkway, Suite 630. 13 Physicist, Nuclear and Directed Energy Concepts, 3322 South Memorial Parkway, Suite 630.