Eric Bentley's "Double" Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUSTLER HOLLYWOOD Real Estate Press Kit

HUSTLER HOLLYWOOD Real Estate Press Kit http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Presentation Overview Hustler Hollywood Overview Real Estate Criteria Store Portfolio Testimonials http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Company History Hustler Hollywood The vision to diversify the Hustler brand and enter the mainstream retail market was realized in 1998 when the first Hustler Hollywood store opened on the iconic Sunset Strip in West Hollywood, CA. Larry Flynt's innovative formula for retailing immediately garnered attention, resulting in coverage in Allure and Cosmopolitan magazines as well as periodic appearances on E! Entertainment Network, the HBO series Entourage and Sex and the City. Since that time Hustler Hollywood has expanded to 25 locations nationwide ranging in size from 3,200 to 15,000 square feet. Hustler Hollywood showcases fashion-forward, provocative apparel and intimates, jewelry, home décor, souvenirs, novelties, and gifts; all in an open floor plan, contemporary design and lighting, vibrant colors, custom fixtures, and entirely viewable from outside through floor to ceiling windows. http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Retail Stores Hustler Hollywood, although now mimicked by a handful of competitors, has stood distinctly apart from peers by offering consumers, particularly couples, a refreshing bright welcoming store to shop in. Each of the 25 stores are well lit and immaculately clean, reflecting a creative effort to showcase a fun but comfortable atmosphere in every detail of design, fixture placement, and product assortment. -

Community in August Wilson and Tony Kushner

FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER By Copyright 2007 Richard Noggle Ph.D., University of Kansas 2007 Submitted to the Department of English and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date defended ________________ 2 The Dissertation Committee for Richard Noggle certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: FROM THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE COLLECTIVE: COMMUNITY IN AUGUST WILSON AND TONY KUSHNER Committee: ________________________ Chairperson, Maryemma Graham ________________________ Chairperson, Iris Smith Fischer ________________________ Paul Stephen Lim ________________________ William J. Harris ________________________ Henry Bial Date approved _______________ 3 ABSTRACT My study examines the playwrights August Wilson and Tony Kushner as “political” artists whose work, while positing very different definitions of “community,” offers a similar critique of an American tendency toward a kind of misguided, dangerous individualism that precludes “interconnection.” I begin with a look at how “community” is defined by each author through interviews and personal statements. My approach to the plays which follow is thematic as opposed to chronological. The organization, in fact, mirrors a pattern often found in the plays themselves: I begin with individuals who are cut off from their respective communities, turn to individuals who “reconnect” through encounters with communal history and memory, and conclude by examining various “successful” visions of community and examples of communities in crisis and decay. -

Outrageous Opinion, Democratic Deliberation, and Hustler Magazine V

VOLUME 103 JANUARY 1990 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONCEPT OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE: OUTRAGEOUS OPINION, DEMOCRATIC DELIBERATION, AND HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL Robert C. Post TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL ........................................... 6o5 A. The Background of the Case ............................................. 6o6 B. The Supreme Court Opinion ............................................. 612 C. The Significance of the Falwell Opinion: Civility and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ..................................................... 616 11. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE ............................. 626 A. Public Discourse and Community ........................................ 627 B. The Structure of Public Discourse ............... ..................... 633 C. The Nature of Critical Interaction Within Public Discourse ................. 638 D. The First Amendment, Community, and Public Discourse ................... 644 Im. PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND THE FALIWELL OPINION .............................. 646 A. The "Outrageousness" Standard .......................................... 646 B. The Distinction Between Speech and Its Motivation ........................ 647 C. The Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................... 649 i. Some Contemporary Understandings of the Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................................................ 650 (a) Rhetorical Hyperbole ............................................. 650 (b) -

Kendall Fields Guide for Mental Health Professionals in The

THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CLINICAL SEXOLOGISTS AT MAIMONIDES UNIVERSITY GUIDE FOR MENTAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN THE RECOGNITION OF SUICIDE AND RISKS TO ADOLESCENT HOMOSEXUAL MALES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CLINICAL SEXOLOGISTS AT MAIMONIDES UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY KENDALL FIELDS NORTH MIAMI BEACH, FLORIDA DECEMBER 2005 Copyright © by Kendall L. Fields All rights reserved ii DISSERTATION COMMITTEE William Granzig, Ph.D., MPH, FAACS. Advisor and Committee Chair James O Walker, Ph.D. Committee Member Peggy Lipford McKeal, Ph.D. NCC, LMHC Committee Member Approved by dissertation Committee Maimonides University North Miami Beach, Florida Signature Date _________________________________ William Granzig, Ph.D. James Walker, Ph.D. _ Peggy Lipford McKeal, Ph.D. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to those who assisted in the formulation of this dissertation: Dr. William Granzig, professor, advisor, and friend, who without his guidance, leadership, and perseverance this endeavor would not have taken place. To Dr. Walker, thank you for your time, patience, insight and continued support. To Dr. McKeal, thanks for you inspiration and guidance. You kept me grounded and on track during times when my motivation was waning. To Dr. Bernie Sue Newman, Temple University, School of Social Administration, Department of Social Work and in memory of Peter Muzzonigro for allowing me to reprint portions of their book. To those professionals who gave of their time to complete and return the survey questionnaires. To my darling wife, Irene Susan Fields, who provided support and faith in me. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

![Volume 36 Issue 32 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8778/volume-36-issue-32-pdf-488778.webp)

Volume 36 Issue 32 [PDF]

Svery Cornellian's Taper ORNELL ALUMNI NEW In the News this Week: Reunions large and colorful. Cornellian Council elects Neal Becker as president, Archie Palmer as executive secretary. The new Alumni Trustees are Charles H. Blair, James W. Parker, and Maurice C. Burritt. Poughkeepsie Regatta won by California crew. Volume 36 Number 32. June 21,1934 sidetrips you want to make, then continue whenever you are ready Suppose you are making an Orient cruise: arrive at Shanghai, and find China more fascinating than you ever dreamed any place could be One of the nicest things about cruising on the famous President Liners Stopover! Visit Hangchow and Soochow, Tientsin .. and Peking, Stay is the absolute freedom they allow you—to sail when you please, stop- as long as you like. Then continue on . on another President Liner over as you like, continue on when you chooseo ORIENT ROUNDTRIPS President Liners sail every week Actually you may go through the Panama Canal to California from Los Angeles and San Francisco via Hawaii and the Sunshine (or New York), to the Orient and back, or Round the World almost Route to Japan, China and the Philippines; every other week from as freely on these great ships as you could on your own private yacht. Seattle, via the fast Short Route. You may go one way, return the other And the fares are no more than for ordinary passagel —stopping over wherever you like, travel on the new S. S. President STOPOVER AS YOU LIKE Regular, frequent sailings of Coolidge and S. S. President Hoover and as many others as you choose the President Liners make it possible for you to stopover exactly of the President Liner fleet. -

Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man Degroot, Anton Degroot, A

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man deGroot, Anton deGroot, A. (2016). Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27708 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3189 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Saying Yes: Collaboration and Scenography of Man Equals Man by Anton deGroot A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN DRAMA CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY 2016 © Anton deGroot 2016 Abstract The following artist’s statement discusses the early inspirations, development, execution of, and reflections upon the scenographic treatment of Bertolt Brecht’s Man Equals Man, directed by Tim Sutherland and produced by the University of Calgary in February of 2015. It details the processes of the set, lights, and properties design, with a focus on the director / scenographer relationship, and an examination of the outcomes. ii Preface It is critical that I mention something at the beginning of this artist’s statement to provide some important context for the reader. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

A Gender Oriented Approach Toward Brecht

A GENDER-ORIENTED APPROACH TOWARDS BRECHTIAN THEATRE: FUNCTIONALITY, PERFORMATIVITY, AND AFFECT IN MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHIDREN AND THE GOOD PERSON OF SZECHWAN by SAADET BİLGE COŞKUN Submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University August 2015 i ii © Saadet Bilge Coşkun All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT A GENDER-ORIENTED APPROACH TOWARDS BRECHTIAN THEATRE: FUNCTIONALITY, PERFORMATIVITY, AND AFFECT IN MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN AND THE GOOD PERSON OF SZECHWAN Saadet Bilge Coşkun Conflict Analysis and Resolution, M.A. Thesis, 2015 Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Hülya Adak Keywords: Bertolt Brecht, epic theatre, performativity, gender, affect This thesis presents a gender-oriented critique of Bertolt Brecht’s theory of epic theatre and his two plays: Mother Courage and Her Children and, The Good Person of Szechwan. Feminist theatre scholars often criticize Brecht’s plays for not paying enough attention to gender issues and merely focusing on a class-based agenda. The main issues that these scholars highlight regarding Brecht’s plays and theory include the manipulation of female figures through functionalizing them in order to achieve certain political goals. Other criticisms focus on how female characters are desubjectified and/or desexualized through this instrumentalism. On the other hand, feminist critics also consider epic theater techniques to be useful in feminist performances. Considering all these earlier criticisms, this thesis aims to offer new perspectives for the gender- focused analysis of epic theatre and Brecht’s later plays. Similar to many other criticisms, I conclude that the embedded instrumentalism of epic theater techniques such as materializing and functionalizing the issues as well as the characters, in most cases leads to stereotyping the female characters. -

Tamwag Fawf000069 Lo.Pdf

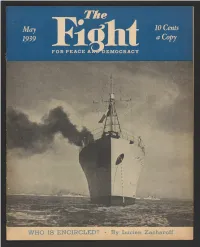

AND NOW— June 15 Cents 1939 World a Copy FOR PEACE AND DEMOCRACY TO THOSE who have read and supported The FIGHT for Peace and Demoer over the years, we wish to announce several changes in the magazine beginning with the June 1939 issue. These improvements in format are designed to provide a livelier, better medium for expressing the American people's struggle against the Fascist war-makers. They come as a result of wide reader interest in the problems of the magazine, as well as the active study of the publishers and the staff. These New Features! @ NAME—The WORLD for Peace and Democracy is a positive improve the app rance of the title, expressing with clarity the constructive aims of the maga- play, mailing and handlin; This change has heen sevei zine, The fight for peace goes on—but it has become ar that in the planning, until jancial arrangements could be worked this fight is conducted on a world scale. © EDITORS—Dr. Harry F. Ward, Helen Bryan, Margaret Forsyth, DEPARTMENTS. ‘Thomas L, Harris, executive secretary of the Ame ‘Thomas L. Harris, Dorothy McConnell and Dr. Max Yergan nL gue, will write a monthly pa; will form the Editorial Board of The WORLD. world pes ‘¢ movement. Other new de} and Recor A number of further new features are being ” © SIZE—The WORLD will measure somewhat smaller than the worked out present size, This will facilitate westand display, the mailing PRICE Please note that the price of The WORLD will be 15 and handling of th le still keeping it within the cents a copy, $1.50 a year After careful consideration, it was range of large, pi ‘orial publications. -

American Repertory Theater Partners with Creative Action Project and 826 Boston on Podcast Play Series

For Immediate Release August 6, 2012 Contact: Kati Mitchell 617-496-2000x8841 [email protected] American Repertory Theater partners with Creative Action Project and 826 Boston on Podcast Play Series Cambridge, MA — The American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) collaborates this summer with 826 Boston, a not-for-profit writing center based in Roxbury, MA, and Creative Action Project, a program of Cambridge Community Services, on a series of site-specific “podcast plays” designed to creatively engage local teens with public spaces around Greater Boston. A.R.T. teaching artists are leading three-day workshops in Cambridge and in Roxbury, in which groups of teenagers learn about the fundamentals of playwriting, practice collaborative storytelling, and participate in a writing immersion exercise at the Fresh Pond Reservation and Franklin Park, respectively. The young playwrights are challenged to locate a place in the park that inspires them, and then imagine a short play that could happen at that site. The resultant plays are recorded as audio, by a mix of teen playwrights and graduate acting students from the A.R.T./MXAT Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University. These plays will be uploaded to the A.R.T. website, as well as the Cambridge Water Department and Franklin Park Coalition websites. The A.R.T., with staff from the Cambridge Water Department and the Franklin Park Coalition, is developing a “theatrical walking tour” map for each park, which park-goers can download along with the podcast series and enjoy on their next visit to the Fresh Pond Reservation or Franklin Park. -

Masterpieces

MORE MASTERPIECES Robert Brustein n 1967, I wrote a controversial essay called “No More Masterpieces,” in which, following the French radical theorist Antonin Artaud (The Theatre and Its Double) and the Polish critic Jan Kott (Shakespeare Our Contemporary), I argued against Islavish reproduction of classical works. I agreed that we had reached the end of some cycle in staging these plays, that actor-dominated classics, particularly Shakespeare, were beginning to resemble opera more than theatre, with their sumptuous settings, brocaded costume parades, and warbled arias. I believed that modern directors were now obliged to freshen our thinking about classical writers in the same way that modern playwrights (notably O’Neill, Cocteau, Sartre, and T.S. Eliot) were freely revisioning the Greeks. My hope was for approaches that would revitalize familiar works wrapped in a cocoon of academic reverence or paralyzed by arthritic convention. Theatre, being a material medium, was settling too cozily into ostentatious display, disregarding the poetic core of a text, its thematic purpose and inner meaning. One way to avoid this, I thought, was through metaphorical investigation by an imaginative director, in close collaboration with a visionary designer, locating the central image of a play through visual icons and a unified style. This was what Peter Brook was doing with the Royal Shakespeare Company in his revitalized productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (channeling its youthful energies into acrobatics and circus acts) and King Lear (translating its vision of old age and death into a bleak visual vocabulary influenced by Beckett). Such produc- tions were making Shakespeare our contemporary through suggestive associations, bringing audiences a fresh appreciation of classics in danger of dying from hardened stage arteries.