School Admissions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oakbank Author: Department for Education (Dfe)

Title: Oakbank Author: Department for Education (DfE) Impact Assessment – Section 9 Academies Act Duty 1. Section 9 of the Academies Act 2010 places a duty upon the Secretary of State to take into account what the impact of establishing the additional school would be likely to be on maintained schools, Academies and institutions within the further education sector in the area in which the additional school is (or is proposed to be) situated. 2. Any adverse impact will need to be balanced against the benefits of establishing the new school. Background 3. Oakbank is an 11-16 school for 560 pupils, due to open in September 2012 with 84 pupils in Year 7. It was proposed by existing Academy sponsor CfBT in partnership with a parent group known locally as WoW (standing for west of Wokingham). The group feel that those living in the rural villages to the West of Wokingham are disadvantaged in securing a school place for their children as a result of the admissions arrangements for other schools in Wokingham which prioritise children living closest to schools. They feel that this means that they get “what’s left”, and have to travel long distances past their closest school. It was envisaged that establishing Oakbank would provide a school closer to home to which these children would be admitted. 4. Oakbank will be situated on the site of the old Ryeish Green School in Wokingham Borough. It is, however, closer to Reading than it is to the town of Wokingham, although the M4 separates the school from the south of Reading. -

Admissions to Secondary School September 2021 - 2022

Admissions to Secondary School September 2021 - 2022 Guide for Parents and Carers - Moving on to Secondary School 1 School Admission Guide Sept 2021 - 2022 | Apply at www.brighterfuturesforchildren.org/school-admissions INTRODUCTION Dear Parent/Carer, We are Brighter Futures for Children and we as smooth and straightforward as possible. took over the delivery of children’s services It contains a lot of detail and it is important that in Reading in December 2018 from Reading you read it carefully and follow the guidance Borough Council. step-by-step to ensure you maximise your We are wholly-owned by Reading Borough chances of reaching a successful outcome for Council but independent of it, with our own staff, you and your child. management team and Board. Throughout this guide you will see references to On behalf of the council, we deliver children’s both Brighter Futures for Children and Reading social care (including fostering and early help), Borough Council, as well as both ‘Children education, Special Educational Needs and Looked After’ and ‘Looked After Children’. We Disabilities (SEND) and youth offending services. use the former and are encouraging others to do so, as we’ve asked our children in care and it’s a Our vision and aim is to unlock resources to help term they prefer. However, as we took over part every child have a happy, healthy and successful way through a school year, this guide will refer to life. both. Part of our education remit is to deliver the However, the information is correct and this school admissions service, in line with local guide gives you a flavour of the full range of authority statutory duties. -

Academy Name LA Area Parliamentary Constituency St

Academy Name LA area Parliamentary Constituency St Joseph's Catholic Primary School Hampshire Aldershot Aldridge School - A Science College Walsall Aldridge-Brownhills Shire Oak Academy Walsall Aldridge-Brownhills Altrincham College of Arts Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Altrincham Grammar School for Boys Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Ashton-on-Mersey School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Elmridge Primary School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Loreto Grammar School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Heanor Gate Science College Derbyshire Amber Valley Kirkby College Nottinghamshire Ashfield Homewood School and Sixth Form Centre Kent Ashford The Norton Knatchbull School Kent Ashford Towers School and Sixth Form Centre Kent Ashford Fairfield High School for Girls Tameside Ashton-under-Lyne Aylesbury High School Buckinghamshire Aylesbury Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School Buckinghamshire Aylesbury Dashwood Primary Academy Oxfordshire Banbury Royston Parkside Primary School Barnsley Barnsley Central All Saints Academy Darfield Barnsley Barnsley East Oakhill Primary School Barnsley Barnsley East Upperwood Academy Barnsley Barnsley East The Billericay School Essex Basildon and Billericay Dove House School Hampshire Basingstoke The Costello School Hampshire Basingstoke Hayesfield Girls School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Oldfield School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Ralph Allen School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Batley Girls' High School - Visual Arts College Kirklees Batley and Spen Batley Grammar School Kirklees Batley -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

Newsletter Dec 2012 Issue 65

Edgbarrow School Issue no. 65 - December 2012 www.edgbarrow.bracknell-forest.sch.uk From the Headteacher As we near the end of the Autumn term I wanted to take the opportunity to bring everybody up-to-date with what’s Our first painting and gardening day of new and what’s been happening at Edgbarrow School. this academic year was held on Saturday 29th September. Again we were very lucky with the support and time offered Well if I take you all way back to by our Mums, Dads and students, who the summer holidays I’m gave up a couple of hours on the day to delighted to report that our paint and garden. We estimate that this GCSE and A-Level results were time we probably saved the school about £3,500. just outstanding this year. At Thankfully it was a beautiful day and our gardeners, of GCSE the students achieved whom there were quite a few, did a sterling job on the 99.4% 5 A*-C or above and 79% 5 A*-C or above front large flower bed and around the front of Reception. including English and Maths. In addition to that over 24% When I showed parents around on the following Monday of our results were A* & A, in fact 174 of 179 students morning, even though it was raining, the school looked achieved 8 A*-C grades. great! As for Hill block, by the end of the day we had painted and decorated entrances, three offices, the three With regards to A-Level results, they were just fantastic. -

Reference: BW00595 Subject: Mental Health for Children I Can Confirm

Reference: BW00595 Subject: Mental Health for Children I can confirm that the CCG does hold some of the information requested; please see responses below: QUESTION Berkshire West CCG I am writing to you regarding the Berkshire West trailblazer area expanding access to mental health care for children and young people. I am trying to understand to what extent the programme is engaging with schools for excluded children. 1. Please could you provide a list of each educational setting the mental health support team is (or has been) active in since its inception. Please note the name and URN or UKPRN where applicable A: 1 Berkshire West West Berkshire Beedon CE Primary School 109950 Berkshire West West Berkshire Bradfield C.E. Primary School 110007 Berkshire West West Berkshire Brightwalton C.E. Primary School 110008 Berkshire West West Berkshire Bucklebury C.E. Primary School 109955 Berkshire West West Berkshire Chaddleworth St. Andrew's CE. 109957 Berkshire West West Berkshire Chieveley Primary School 109810 Berkshire West West Berkshire Cold Ash St Mark's CE School 109958 Berkshire West West Berkshire Compton C.E. Primary School 109959 Berkshire West West Berkshire Curridge Primary School 109811 Berkshire West West Berkshire Francis Baily Primary School 109831 Berkshire West West Berkshire Hampstead Norreys CE Primary School 109964 Berkshire West West Berkshire Hermitage Primary School 109815 Berkshire West West Berkshire Hungerford Primary School 109816 Berkshire West West Berkshire Inkpen Primary School 109817 Berkshire West West Berkshire John O'Gaunt School 142822 Berkshire West West Berkshire Kennet School 136647 Berkshire West West Berkshire Kintbury St Marys C. E. 109967 Berkshire West West Berkshire Lambourn CE Primary 146307 Berkshire West West Berkshire Parsons Down Junior School 109923 Berkshire West West Berkshire Shefford C.E. -

2013 Admissions Cycle

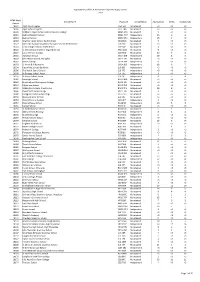

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2013 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 15 6 4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy (formerly Upper School) Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 9 <3 <3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 5 4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 18 6 6 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 8 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 18 9 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 9 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 8 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon -

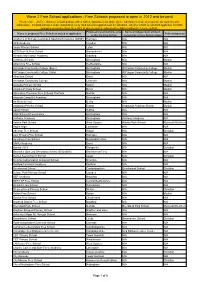

Free Schools Proposed to Open in 2012 and Beyond

Wave 2 Free School applications - Free Schools proposed to open in 2012 and beyond Please note - All Free Schools, including those with a faith designation must abide by the Admissions Code and operate fair and inclusive admissions. If a faith school is under subscribed every child who has applied must be admitted - whether a faith or non-faith applicant. If a faith school is oversubscribed, then 50% of places must be allocated to children without reference to faith. Proposed Local Authority area Name of independent school if Name of proposed Free School as stated in application Faith designation to site the Free School converting to Free School status Academy of Entrepreneurship & Sporting Excellence (AESE) Haringey N/A N/A ACE Academy Croydon N/A N/A Acorn Primary School Luton N/A N/A AGS Post 16 Free School Warwickshire N/A N/A Airedale Montessori Academy Bradford N/A N/A Al Hikma Schools Birmingham N/A Muslim Alban City Free School Hertfordshire N/A N/A Al-Furqan Community College (Boys) Birmingham Al-Furqan Community College Muslim Al-Furqan Community College (Girls) Birmingham Al-Furqan Community College Muslim Alhambra School Brent N/A N/A Al-Ihsaan Community College Leicester N/A Muslim Al-Quba Primary School Merton N/A Muslim Alsalam Primary School Brent N/A Muslim Alternative Provision Free Schools Thetford Norfolk N/A N/A Amanah Camp Hill Academy Birmingham N/A N/A An Noor School Derby N/A Muslim Andalusia Primary School Bristol Andalusia Academy Bristol Muslim Apollo School Suffolk N/A N/A AQA School Of Excellence Birmingham -

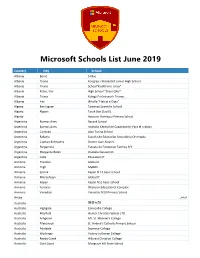

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St. -

Admissions to Secondary School September 2021 - 2022

Admissions to Secondary School September 2021 - 2022 Guide for Parents and Carers - Moving on to Secondary School 1 School Admission Guide Sept 2021 - 2022 | Apply at www.brighterfuturesforchildren.org/school-admissions INTRODUCTION Dear Parent/Carer, We are Brighter Futures for Children and we as smooth and straightforward as possible. took over the delivery of children’s services It contains a lot of detail and it is important that in Reading in December 2018 from Reading you read it carefully and follow the guidance Borough Council. step-by-step to ensure you maximise your We are wholly-owned by Reading Borough chances of reaching a successful outcome for Council but independent of it, with our own staff, you and your child. management team and Board. Throughout this guide you will see references to On behalf of the council, we deliver children’s both Brighter Futures for Children and Reading social care (including fostering and early help), Borough Council, as well as both ‘Children education, Special Educational Needs and Looked After’ and ‘Looked After Children’. We Disabilities (SEND) and youth offending services. use the former and are encouraging others to do so, as we’ve asked our children in care and it’s a Our vision and aim is to unlock resources to help term they prefer. However, as we took over part every child have a happy, healthy and successful way through a school year, this guide will refer to life. both. Part of our education remit is to deliver the However, the information is correct and this school admissions service, in line with local guide gives you a flavour of the full range of authority statutory duties. -

Royal Holloway, University of London Aspiring Schools List

Royal Holloway, University of London Aspiring Schools list Accrington and Rossendale College Addey and Stanhope School Alde Valley School Alder Grange School Aldercar High School Alec Reed Academy All Saints Academy Dunstable All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham All Saints Church of England Academy Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Altrincham College of Arts Amersham School Appleton Academy Archbishop Tenison's School Ark Evelyn Grace Academy Ark William Parker Academy Armthorpe Academy Ash Hill Academy Ashington High School Ashton Park School Askham Bryan College Aston University Engineering Academy Astor College (A Specialist College for the Arts) Attleborough Academy Norfolk Avon Valley College Avonbourne College Aylesford School - Sports College Aylward Academy Barnet and Southgate College Barr's Hill School and Community College Baxter College Beechwood School Belfairs Academy Belle Vue Girls' Academy Bellerive FCJ Catholic College Belper School and Sixth Form Centre Benfield School Berkshire College of Agriculture Birchwood Community High School Bishop Milner Catholic College Bishop Stopford's School Blatchington Mill School and Sixth Form College Blessed William Howard Catholic School Bloxwich Academy Blythe Bridge High School Bolton College Bolton St Catherine's Academy Bolton UTC Boston High School Bourne End Academy Bradford College Bridgnorth Endowed School Brighton Aldridge Community Academy Bristnall Hall Academy Brixham College Brockhill Park Performing Arts College Brompton Academy Brooklands -

Name of Accepted School in TPS 3 Dimensions Abberley Hall School

Name of Accepted School in TPS 3 Dimensions Abberley Hall School Abbey Gate College Abbots Bromley School for Girls Abbot's Hill Aberdour School Abingdon House School Abingdon School Acorn Park School Acorns School Akeley Wood School Aldenham School Alderley Edge School for Girls Alderwasley Hall Aldwickbury School All Hallows School Alleyn Court School Alleyn's School Alpha Preparatory School Alton School Ambitious about Autism Amesbury School Ampleforth College Anderson School Annemount School Appleford School Appletree Treatment Centre Ltd Arnfield Independent School Arnold House School Arnold Lodge School Arnold School Ashbridge Independent School Ashcroft School Ashton House School Ashville College Ashwicke Hall School Atlantic College Aurora Eccles School Aurora Hanley School Aurora Hedgeway School Aurora Meldreth Manor School Aurora Redehall School Austin Friars School Avalon School Educational Trust Avenue Nursery & Pre Prearatory School Avocet House School Ayscoughfee Hall School Aysgarth School Babington House School Bablake School Bancroft's School Banstead Preparatory School Barlborough Hall School Barnard Castle School Barnardiston Hall School Bassett House School Battle Abbey School Beachborough School Trust Ltd Bedales School Bede's Senior School Bedford Girls School Bedford Modern School Bedford School Beech lodge School Beechwood Park School Beechwood Sacred Heart School Beeston Hall School Beis Yaakov Girls School Belmont Grosvenor School Belmont School Belvedere Preparatory School Benenden School (Kent) Ltd Berkhampstead