Considerations for the Anthropocene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RADICAL ARCHIVES Presented by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU Curated by Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh

a/p/a RADICAL ARCHIVES presented by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU curated by Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh Friday, April 11 – Saturday, April 12, 2014 radicalarchives.net Co-sponsored by Asia Art Archive, Hemispheric Institute, NYU History Department, NYU Moving Image Archive Program, and NYU Archives and Public History Program. Access the Internet with NYU WiFi SSID nyuguest login guest2 password erspasta RADICAL ARCHIVES is a two-day conference organized around the notion of archiving as a radical practice, including: archives of radical politics and practices; archives that are radical in form or function; moments or contexts in which archiving in itself becomes a radical act; and considerations of how archives can be active in the present, as well as documents of the past and scripts for the future. The conference is organized around four threads of radical archival practice: Archive and Affect, or the embodied archive; Archiving Around Absence, or reading for the shadows; Archives and Ethics, or stealing from and for archives; and Archive as Constellation, or archive as method, medium, and interface. Advisory Committee Diana Taylor John Kuo Wei Tchen Peter Wosh Performances curated Helaine Gawlica (Hemispheric Institute) with assistance from Marlène Ramírez-Cancio (Hemispheric Institute) RADICAL ARCHIVES SITE MAP Friday, April 11 – Saturday, April 12 KEY 1 NYU Cantor Film Center 36 E. 8th St Restaurants Coffee & Tea 2 Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU 8 Washington Mews Cafetasia Cafe Nadery Oren’s 3 NYU Bobst -

Calendar of Events

Calendar of Events The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.), along with hundreds of organizations in the archives community across New York State, proudly presents New York Archives Week October 6-12, 2013, coordinating commemorative activities throughout the New York City Metropolitan area. New York Archives Week is an annual celebration aimed at informing the general public of the diverse array of archive materials accessible in the Metropolitan New York City region. The celebration includes open houses, lectures, workshops and behind-the-scenes tours designed to illustrate the importance of historical records. All New York Archives Week events are free and open to the public. Following is a calendar overview of the New York Archives Week events. Please see the “Event Descriptions” pages for details about each event, including RSVP instructions. For the latest news about New York Archives Week visit: www.nycarchivists.org. The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) thanks MetLife for being a major sponsor of New York Archives Week. A.R.T. also thanks the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation for their generous support of New York Archives Week. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 5 (BONUS DAY!) Mount Sinai Archives; “Reaching Out to the Inside: Internal Publications Over the Years,” Exhibit, 7:00 a.m.- 11:00 p.m., all week, exhibit closes December 31, 2013. The New York Society Library; “Extraordinary Gifts: Rare Books Presented to the New York Society Library 1754-2012,” Saturday 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m, open daily through December 31, 2013, see ongoing exhibits and programs below for times for each day. -

Maggie Schreiner

Maggie Schreiner Professional Experience Manager of Archives and Special Collections, August 2019 – Present Archivist, February 2018 – August 2019 Brooklyn Historical Society, Brooklyn, NY • Collection Development: Build and maintain relationships with collections donors, conduct site visits to assess and survey potential donations, prepare proposed donations for assessment by the Collections Committee; draft and finalize deeds of gifts, accession new material in consultation with donors. • Arrangement and Description: Oversee archival description program through supervision of processing, maintaining and revising policies and procedures, determining processing priorities, and implementation of iterative processing. Prioritize materials for conservation or digitization. • Digital Projects: Manage digital projects, including collections digitization, development of digital access platforms, and the digital preservation program. Responsible for liaising with vendor IT and digitization services, and consultants. • Collections Management: Overall stacks maintenance and location control for all archival collections across multiple facilities; monitoring of environmental conditions in collections storage spaces. • Records Retention: Manage business records of Brooklyn Historical Society, update records retention schedule, and support staff in implementing retention schedule. • Supervision: Supervision of 1 FTE Archivist, as well as FT and PT project staff, graduate interns, and volunteers. • Administration: Budget development and tracking for -

Subject Files -- File List Updated September 7, 2019 These Files Contain Small Pieces of Ephemera -- Postcards, Handbills, Flyers, and Other Single-Sheet Papers

Subject Files -- file list Updated September 7, 2019 These files contain small pieces of ephemera -- postcards, handbills, flyers, and other single-sheet papers. Bold -- “Parent” Categories Italics -- Files that share the name with their “parent” categories. The folders do not actually say “General” Strikethrough -- File is Missing DO YOU NEED TO CREATE A NEW SUBJECT FILE? It’s possible that there’s no subject file for the material you’re putting away. In that case, please find a file folder and write the subject on that. File it in correct alphabetical order, and then write your new subject on this sheet in pen or pencil. Thanks! Note on Mini Liu subject files: these files were donated in their current form by a donor who had maintained her own subject files. They have been maintained in their original condition, but have been inter filed with our existing subject file collection for ease of access. 15-M Movement AANCO AAUPA meeting minutes (Asian American Union for Political Action) (Mini Liu subject file) AAUPA -- Jazz for Jackson (Mini Liu subject file) ABC No Rio Abu Jamal, Mumia Active Resistance Abu-Jamal, Mumia Act Up Activism Ad Busting / Billboard Reclamation Africa Afro Europes Conference Agitarte / Papel Machete / When We Fight We Win (Puerto Rico / Boston / NOLA) Agriculture AIDS/HIV Activism AIDS - Spain Alliance for Labor and Community Allied Media Conference- AMC Alternate Media Amnesty International Amsterdam Anarchism ● flyers ● Academic articles and papers ● Catalunya ● Japan ● Tactics ● Oregon ● Mexico Anarchist ● -

Big Dog Days by Hannah Nussbaum

It was the penultimate night of August and I was ready for anything, dressed in a gauzy PG-13 outfit, standing on the patio of a soft-boiled party filled with talking backs and healthy-looking pink mouths. Things were just starting to get boisterous and someone standing near me was vaporizing chartreuse liquor, and wisps of green gas were wafting around the patio like little souls on their way to the underworld. I sipped and shuffled, posed and pouted, eyes on a platter of finger food balanced on the bar. Eventually I was approached by a beautiful boy with big rubber shoes and a blue hood pulled tightly around his ears. He introduced himself and complimented my look and soon we were talking about the beach, which was all anybody talked about those days—the liminal state of affairs down there, the big weird question mark stamped on our city. The beach in our city had once been a normal, generic beach, you know the kind, with sand, surf and all the regular seaside fixings. Then one summer the entire coast had been purchased by either an asset management company or a real estate investment trust—it wasn’t clear which—and what happened next was a series of ownership changes, financing issues, construction delays, legal challenges and chronically delayed re-opening dates. The beach changed hands several times and some scaffolding was erected around it while the project plans were being ironed out. We were told that the 587 acres of coastal wetlands were supposed to be renovated into 2.1 million square feet of beachfront space and 1 million square feet of to-be-determined on a 206-acre tract, with the remainder to be converted into stormwater retention basins. -

Ecologise Reading Material for Ecologise Camps

ECOLOGISE READING MATERIAL FOR ECOLOGISE CAMPS Sangatya Sahitya Bhandar CONTENTS 1. Ecologise Camps: An Introduction Page 2 2. Nature's Methods Of Soil Management Albert Howard Page 5 3. Humanity Does Not Know Nature Masanobu Fukuoka Page 8 4. On a Perspective for Renaissance of Agriculture Venkat Page 11 5. Walking Henry David Thoreau Page 15 6. The Proper Use of Land E F Schumacher Page 19 7. Gaia’s Will Manu Kothari and Lopa Mehta Page 24 8. Fire & Accounting Mansoor Khan Page 34 9. Waiting for a Genius Page 38 Lu Hsun For more information, visit: www.ecologise.in 1 Ecologise Camps: An Introduction “When the last tree has been cut down, the last fish caught, the last river poisoned, only then will we realize that one cannot eat money.” Native American Saying We now live in an age of ecological change and turmoil that is unprecedented in scale and rapidity in the history of the earth. We are grappling with a slew of converging crises, most of which are the direct result of human activity and the ‘religion’ of ‘Growth and Development’ that we have embraced in the past 250 years of industrialisation. Climate change, natural resource depletion, species extinction, environmental degradation, population pressure and human conflict resulting in large scale refugee crises are some of the problems we have to contend with. Some of these, like climate change, are reaching tipping points beyond which changes become irreversible. Humans are the only species on earth that have had such a massive direct impact on the environment in which we live, by virtue of the tools and technologies that we have developed, in the process of the ‘development’ of our ‘civilization’. -

Migration and Irregular Work in Austria: a Case Study of the Structure And

www.ssoar.info Migration and irregular work in Austria: a case study of the structure and dynamics of irregular foreign employment in Europe at the beginning of the 21st Century Jandl, Michael; Hollomey, Christina; Gendera, Sandra; Stepien, Anna; Bilger, Veronika Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Jandl, M., Hollomey, C., Gendera, S., Stepien, A., & Bilger, V. (2008). Migration and irregular work in Austria: a case study of the structure and dynamics of irregular foreign employment in Europe at the beginning of the 21st Century. (IMISCoe Reports). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271786 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Migration and Irregular Work in Austria IMISCOE (International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion) IMISCOE is a Network of Excellence uniting over 500 researchers from various institutes that specialise in migration studies across Europe. Networks of Excellence are cooperative research ventures that were created by the European Commission to help overcome the fragmentation of international studies. They amass a crucial source of knowledge and expertise to help inform European leadership today. -

Qe7ybugnpjvupq3u.Pdf

EDITOR'S LETTER Stepping Into History By Rachel Riederer Brooklyn, NY June 8, 2016 In this month’s Editor’s Letter, Rachel Riederer talks with artist Alicia Grullón about reenacting crucial political moments, from labor actions in the Bronx to famous Texas filibusters. I remember crowding around a laptop with friends to watch Wendy Davis’s filibuster in the Texas State Senate. Her eleven-hour speech was an attempt to block a bill imposing restrictions that would cause many abortion clinics to close. Even on a tiny computer screen and halfway across the country, you could feel the energy and tension in the statehouse, all the way up until she completed the filibuster, to the raucous chanting of supporters that filled the statehouse hallways. So when I heard about Alicia Grullón’s reenactment of the filibuster at BRIC House as part of the exhibition “Whisper or Shout: Artists in the Social Sphere,” I wondered what it would be like to see a a reenactment of a moment that had already been so well documented. Grullón’s performance piece was urgent and moving. Hearing the text of the filibuster spoken aloud by someone who is not a lawyer or a politician gave the words new weight, and it was striking to see Grullón in person, dealing with fatigue as well as the often openly hostile environment. After her performance, we talked about how she came to incorporate reenactments into her artistic practice, what it means to change the identity of one of the actors in a political moment, and the radical empathy of putting yourself into someone else’s shoes. -

In New York City

Labor Archives Labor Library and Robert F. Wagner Wagner F. Robert and Library on Organizations, Tamiment Organizations, on Brooklyn, rent strikes in Harlem and and Harlem in strikes rent Brooklyn, Printed Ephemera Collection Ephemera Printed integration struggles at Stuyvesant Town and in in and Town Stuyvesant at struggles integration first citywide federation of tenant tenant of federation citywide first associations in NYC (1938). (1938). NYC in associations resistance to urban renewal in the South Bronx, Bronx, South the in renewal urban to resistance history of tenant struggle, including: neighborhood neighborhood including: struggle, tenant of history Wide Tenants Council was the the was Council Tenants Wide Knickerbocker Village, the City City the Village, Knickerbocker rent regulation system forms the backdrop to a rich rich a to backdrop the forms system regulation rent Formed in 1936 by residents of of residents by 1936 in Formed The creation and subsequent dismantling of the the of dismantling subsequent and creation The affordable housing from the 1940s to the present. present. the to 1940s the from housing affordable of collective action by NYC tenants for decent and and decent for tenants NYC by action collective of Tenants Organize in New York City York New in Organize Tenants , an exploration exploration an , We Won’t Move: Move: Won’t We Interference Archive presents presents Archive Interference Metropolitan Council on Housing on Council Metropolitan Private collection of the of collection Private decontrol (circa 1975). 1975). (circa decontrol apartments affected by vacancy vacancy by affected apartments rent stabilization to most of the the of most to stabilization rent Protection Act, which extended extended which Act, Protection support of the Emergency Tenant Tenant Emergency the of support action for housing justice. -

Peak Oil and the Everyday Complexity of Human Progress Narratives

Peak Oil and the Everyday Complexity of Human Progress Narratives John C. Pruit University of Missouri The “big” story of human progress has polarizing tendencies featuring the binary options of progress or decline. I consider human progress narratives in the context of everyday life. Analysis of the “little” stories from two narrative environments focusing on peak oil offers a more complex picture of the meaning and contours of the narrative. I consider the impact of differential blog site commitments to peak oil perspectives and identify five narrative types culled from two narrative dimensions. I argue that the lived experience complicates human progress narratives, which is no longer an either/or proposition This is going to be an environmental disaster of unprecedented proportions and the only thing that people seem to really care about is keeping the Mississippi open to shipping traffic so that BAU [business as usual] can continue. I weep for the wetlands and what their loss will mean. “FMagyar” April 30, 2010 What's the worst the doomers can moan about now? An oil spill (not even a big one by historical standards) and a bit of toxic mess in Canada. Woo, I'm so scared! Come on doomers, you can do better than this! :) “Mr Potato Head” July 9, 2010 Oil and oil-related events such as the 2010 BP spill in the Gulf of Mexico are part of the story of human progress and important to how people story their own lives. Oil powers lifestyles and plays a role in everything from transportation to food production. -

The SRRT Newsletter

Digital image fromDigital image October 2020 Issue 212 Shutterstock . The SRRT Newsletter Libraries and Voting During COVID-19 Dear The SRRT NewsletterReaders, I hope the best for your health and your work as we continue with the challenge of COVID-19. In this issue, we have taken a closer look at what libraries are doing to support voting in their communities. The role of libraries in helping people register and vote can be a critical one, especially in states that have so many barriers to voting, such as requiring a witness to sign a mail-in ballot (e.g., Wis- Inside this issue consin), requiring a copy of an acceptable ID to be included with a mail-in ballot (e.g., Alabama) or not allowing ballot drop boxes (e.g., Tennessee). We encour- From the Coordinator-Elect.........2 age libraries to provide as much information as possible for local voters, so they know where and how to register and vote and what they need to do that. There are some excellent websites that Call for SRRT Elected Offices ........3 provide specific information about local voting and registrations, such asVote.org. VoteRiders helps Voices From the Past ...................3 people actually obtain the ID they need. GODORT has put together a Voting and Election toolkit. HHPTF has also put together a template that can be used to guide libraries in providing relevant and So All Can Attend .........................4 timely accurate voting and registration information for each community. The document also pro- FTF News .....................................5 vides a short annotated list of recommended websites. -

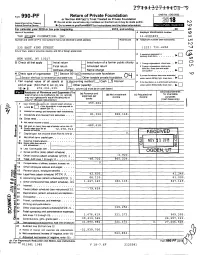

2018 Or Tax Year Beginning , 2018, and Endina Name of Foundation a Employer Ldentlf1catlon Number the PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Department o,,t the Treasury ... Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service .,. Go to www.irs.gov/Fonn990PF for instructions and the latest information For ca endar vear 2018 or tax year beginning , 2018, and endina Name of foundation A Employer ldentlf1catlon number THE PFJEER FOUNDATION, INC. 13-6083839 Number and street (or PO box number 11 ma1l 1s not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see 1nstruct1ons) 235 EAST 42ND STREET ( 212) 733 -4250 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption appllcat1on 1s pending, check here. • • NEW YORK, NY 10017 G Check all that apply Initial return ,___ Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ1zat1ons. check here. ,___ Final return ~ Amended return 2 F ore1gn orgamzat1ons meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name change computat1on • • • • • • • • H Check type of organization X Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation oy E If private foundation status was terminated D _.___.n __S.::.e.::.c::.:t::..:10:.:.n.:...4...:..::.94..;..7.:...'<:c:a:u..H1,_,, >...:n::..:o:..:n::..:e:::.x:.=e::..:m.:.,10:.:t....:c:.:.h:.=a::..:ri:.=ta:.:b:.:.le:;....::.tr.:::u.:::st:....__,_""._,_=O:.:t::..:h=e.:...r.:.ta=xa:;:=b:..::le;...c..:.:Pn.:.v::::ac:cte;....:.f.:::o.;:u::..:n.=d.=ac.::t1.:::o::..:n n ___ ..:__--l under section S07(b)(1)(A) check here .