001-324 Солтис 5-09-14.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dvoretsky Lessons 48

The Instructor The Effects of Replaying I have frequently mentioned, in books and articles, an effective training method: replaying specially selected positions – positions which cannot be “resolved” from beginning to end, so there is really no sense in trying. Instead, players must find, in succession, a series of correct decisions independently (or nearly independently) of each other. In the majority of such exercises, play continues for a minimum of ten moves, although sometimes longer. After all, a shorter variant could in fact be calculated from beginning to end, which would then abolish it as a playing exercise. But The there are sometimes exceptions. The brilliant attack from the following game, which remained hidden in the Instructor annotations, and which is now offered for your consideration, has for some reason never become widely known, although its basic ideas were demonstrated Mark Dvoretsky in Mikhail Botvinnik’s annotations from his book 1941 Match-Tournament. But even those who are familiar with Botvinnik’s analysis will be none the worse for it – for they too will see sharp new variations. Botvinnik - Bondarevsky Leningrad/Moscow 1941 So – you have White. Try to find each move in turn, taking Black’s replies from the following text. Or you might play out this fragment against a friend: he will also find it a problem requiring deep insight into the position. 39.Ne2xd4! In combination with White’s next move, this is a rather obvious exchange: in this way, White gets the opportunity to speculate on the pin along the a1-h8 diagonal. In the game, Botvinnik played the much weaker 39.Ng3?, and after 39...Qe6! 40.Re2 Be3, he ought to have been dead lost: White has neither his pawn, nor any sort of compensation for it. -

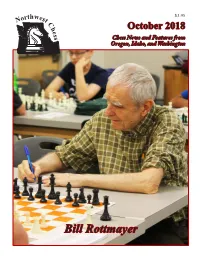

Bill Rottmayer on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the Oldest Participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open

$3.95 orthwes N t C h October 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Idaho, and Washington Bill Rottmayer On the front cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the oldest participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open. Bill has participated in most Spokane Chess Club events the last few years. Photo credit: James Stripes. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Dustin Herker at the Las Vegas International Festival where Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. he won first place U1000. Photo credit: Nancy Keller. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich, Alex Machin, Eric Holcomb. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. -

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Ebook Download Chess for Everyone: a Complete Guide for the Beginner

CHESS FOR EVERYONE: A COMPLETE GUIDE FOR THE BEGINNER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert M Snyder | 205 pages | 30 Dec 2008 | iUniverse | 9780595482061 | English | Bloomington IN, United States Chess for Everyone: A Complete Guide for the Beginner PDF Book The antithesis of the defensive principle: strive to separate the King and Knight, know the winning maneuvers. White to play wins, whereas black to play is a draw This is in accordance to the principle of Rook passiveness. In some cases, on-site registration might not be offered at all! About Simon Pavlenko. Another complicated maneuver which requires white to make the best of his Knight-Bishop duo. Doubled pawns are a liability, but when your opponent has none, they can be a good thing. Balance action with reflection. Return to Book Page. Design Co. Once you learn the game you can move on to playing chess online. If you're buying a used kiln, check for obvious damage, such as cracks in the metal broken fire- bricks and damage to the heating elements. We list them for you and discuss their success. Before you move into those specialized techniques and strategies, however, you do need to have a complete understanding of the opening phase. You are basically trusting some anonymous VPN company not to impliment a man-in-the-middle attack on you. Kiln size is another consideration. How many other guides explain the actually playing environment? Not only does it give you the basic tactics and strategy but it also outlines the rules you need to win. Filed to: VPN Services. -

Aims: to Enable Participants to Teach Young and Gifted Players in Schools

FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles 1. Objective: To educate and certify Trainers and Chess-Teachers on an international basis. This FIDE Trainers’ Seminar for FIDE Trainer Titles Diploma is approved by FIDE and the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG). The seminar is co-organised by the FIDE, the European Chess Union (ECU), the FIDE Trainers’ Commission (TRG), the Russian Chess Federation and the Russian Chess Academy. 2. Dates: 8th October to 13th October 2013. 3. Location: Moscow, Russia. 4. Participants - Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: FIDE/TRG will award the following titles, according to the approved TRG Guide: 1.2. Titles’ Descriptions / Requirements / Awards: 1.2.2. FIDE Trainer (FT) 1.2.2.1. Scope / Mission: a. Boost international level players in achieving playing strengths of up to FIDE ELO rating 2450. b. National examiner. 1.2.2.2. Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: a. Proof of national trainer education and recommendation for participation by the national federation. b. Proof of at least 5 years activity as a trainer. c. Achieved a career top FIDE ELO rating of 2300 (strength). d. TRG seminar norm. 1.2.2.3. Title Award: a. By successful participation in a TRG Seminar. b. By failing to achieve the FST title (rejected application). 1.2.3. FIDE Instructor (FI) 1.2.3.1. Scope / Mission: a. Raised the competitive standard of national youth players to an international level. b. National examiner. c. Trained players with rating below 2000. FIDE Trainers’ Seminar - Moscow 2013 1 1.2.3.2. Qualification / Professional Skills Requirements: a. Proof of national trainer education and recommendation for participation by the national federation. -

Livros De Xadrez

LIVROS DE XADREZ No. TÍTULO Autor Editora 1 100 Endgames You Must Know Jesus de la Villa New In Chess 2 Ajedrez - La Lucha por la Iniciativa Orestes Aldama Zambrano Paidotribo 3 Alexander Alekhine Alexander Kotov R.H.M. Press 4 Alexander Alekhine´s Best Games Alexander Alekhine Batsford Chess 5 Analysing the Endgame John Speelman Batsford Chess 6 Art of Chess Combination Znosko-Borovsky Dover 7 Attack and Defence M.Dvoretsky & A.Yusupov Batsford Chess 8 Attack and Defence in Modern Chess Tactics Ludek Pachman RPK 9 Attacking Technique Colin Crouch Batsford Chess 10 Better Chess for Average Players Tim Harding Dover 11 Bishop v/s Knight: The Veredict Steve Mayer Ice 12 Bobby Fischer My 60 Memorable Games Bobby Fischer Faber & Faber Limited 13 Bobby Fischer Rediscovered Andrew Soltis Batsford 14 Bobby Fischer: His Aproach to Chess Elie Agur Cadogan 15 Botvinnik - One Hundred Selected Games M.Botvinnik Dover 16 Building Up Your Chess Lev Alburt Circ 17 Capablanca Edward Winter McFarland 18 Chess Endgame Quis Larry Evans Cardoza Publishing 19 Chess Endings Yuri Averbach Everyman Chess 20 Chess Exam and Training Guide Igor Khmelnitsky I am Coach Press 21 Chess Middlegames Yuri Averbach Cadogan Chess 22 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 23 Chess Praxis Aron Nimzowitsch Hays Publishing 24 Chess Self-Improvement Zenon Franco Gambit 25 Chess Strategy for the Tournament Player Alburt & Palatnik Circ 26 Creative Chess Amatzia Avni Cadogan Chess 27 Creative Chess Opening Preparation Viacheslav Eingorn Gambit 28 Endgame Magic J.Beasley -

188 Rebusland

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS number 188 March 31, 2020 REBUSLAND Jeff Coakley & Andrey Frolkin Strange days have found us. But life goes on. This article, long in the planning, categorises the four basic types of chess rebuses and presents two original examples of each. An index to our joint compositions published since 2016 is also appended. The list includes 25 problems from the Puzzling Side. Here is number 26, dedicated to a mutual musical hero, Jim Morrison of the Doors. Rebus 26 w________w“Morrison” [wdwdwdwd] [dwdwdwdw]M [wdwdwdwd] [dwdwdwdw]o r i [wdwdwdwd] [dwdwdwdw]o R n [wdwdwdwd] [dwdwdwdw]s s n w--------w Each letter represents a different type of piece. Uppercase is one colour, lowercase is the other. Determine the position and, if possible, the last move. GREETINGS FROM Rebusland! A rebus is an exercise in deductive reasoning, for composers and solvers. The analysis is primarily a process of elimination, discarding piece assignments with impossible consequences until only the truth remains. Identifying illegal positions is an essential skill. One useful tool we developed in this regard is pro-passer theory, described in detail with the solution to the next problem. This rebus is very complicated, like the times we live in. Stay healthy. Rebus 27 “Healthy” w________w [wdwdwdwd]e L [dwdwdwdw]HH HH a [wdwdwdwd]H H HH [dwdwdwdw]Et [wdwdwdwd]AL y [dwdwdwdw]h h h [wdwdwdwd]hhh hhTY [dwdwdwdw] w--------w Each letter represents a different type of piece. Uppercase is one colour, lowercase is the other. Determine the position and the last move. The first two problems were standard rebuses. -

The Old Indian Move by Move

Junior Tay The Old Indian move by move www.everymanchess.com About the Author is a FIDE Candidate Master and an ICCF Senior International Master. He is a for- Junior Tay mer National Rapid Chess Champion and represented Singapore in the 1995 Asian Team Championship. A frequent opening surveys contributor to New in Chess Yearbook, he lives in Balestier, Singapore with his wife, WFM Yip Fong Ling, and their dog, Scottie. He used the Old Indian Defence exclusively against 1 d4 in the 2014 SportsAccord World Mind Games Online event, which he finished in third place out of more than 3000 participants. Also by the Author: The Benko Gambit: Move by Move Ivanchuk: Move by Move Contents About the author 3 Series Foreword 5 Bibliography 6 Introduction 7 1 The Classical Tension Tussle 17 2 Sämisch-Style Set-Ups and Early d4-d5 Systems 139 3 Various Ideas in the Fianchetto System 274 4 Marshalling an Attack with 4 Íg5 and 5 e3 395 5 Navigating the Old Indian Trail: 20 Questions 456 Solutions 467 Index of Variations 490 Index of Games 495 Foreword Move by Move is a series of opening books which uses a question-and-answer format. One of our main aims of the series is to replicate – as much as possible – lessons between chess teachers and students. All the way through, readers will be challenged to answer searching questions and to complete exercises, to test their skills in chess openings and indeed in other key aspects of the game. It’s our firm belief that practising your skills like this is an excellent way to study chess openings, and to study chess in general. -

Course Notes and Summary

FM Morefield’s Chess Curriculum: Course Review This PDF is intended to be used as a place to review the topics covered in the course and should not be used as a replacement. Feel free to save, print, or distribute this PDF as needed. Section 1: Background Information History ● Chess is widely assumed to have originated in India around the seventh century. ● Until the mid-1400s in Europe, chess was known as shatranj, which had different rules than modern chess. ● Some well-known authors and chess players from that time period are Greco, Lucena, and Ruy Lopez. ● The Romantic Era lasted from the late 18th century until the middle of the 19th century, and was characterized by sacrifices and aggressive play. ● Chess has widely been considered a sport since the late 1800s, when the World Chess Championship was organized for the first time. Other ● Chess is considered a game of planning and strategy because it is a game with no hidden information, where you and your opponent have the same pieces, so there is no luck. ● Studying chess seriously can bring you many benefits, but simply playing it won’t make you smarter. Section 2: Rules of the Game Setting Up the Board ● There are sixty-four squares on the board, and thirty-two pieces (sixteen per player). ● Each player’s pieces are made up of eight pawns, two knights, two bishops, two rooks, a queen, and a king. ● There are two players, Black and White. White moves first. ● If you’re using a physical board, rotate the board until there is a light square on the bottom right for each player. -

April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT

Volume 48, Number 2 COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION April 2021 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT COLORADO SCHOLASTIC ONLINE CHAMPIONSHIP Volume 48, Number 2 Colorado Chess Informant April 2021 From the Editor With measured steps, the Colorado chess scene may just be com- ing back to life. It has been announced that the Colorado Open has been sched- uled for Labor Day weekend this year - albeit with safety proto- cols in place. Be sure to check out the website as the date nears (www.ColoradoChess.com) because as we are aware, things The Colorado State Chess Association, Incorporated, is a could change. The Denver Chess Club has also announced a Section 501(C)(3) tax exempt, non-profit educational corpora- tournament in June of this year - go to their website tion formed to promote chess in Colorado. Contributions are (www.DenverChess.com) for more information on that one. tax deductible. It is with a heavy heart and profound sadness that a friend and Dues are $15 a year. Youth (under 20) and Senior (65 or older) ‘chess bud’ of mine has passed away. Not long after his 70th memberships are $10. Family memberships are available to birthday in January, Michael Wokurka collapsed at his home on additional family members for $3 off the regular dues. Scholas- the 22nd - and never regained consciousness. No prior warning tic tournament membership is available for $3. or health issues were known. His obituary online is listed here: ● Send address changes to - Attn: Alexander Freeman to the https://tinyurl.com/2rz9zrca. He loved the game of chess, and email address [email protected]. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

The Inner Game of Chess: How to Calculate and Win Online

ZmKzi [Read download] The Inner Game of Chess: How to Calculate and Win Online [ZmKzi.ebook] The Inner Game of Chess: How to Calculate and Win Pdf Free Andrew Soltis audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #736467 in eBooks 2015-04-23 2015-04-23File Name: B00WL76LTE | File size: 25.Mb Andrew Soltis : The Inner Game of Chess: How to Calculate and Win before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Inner Game of Chess: How to Calculate and Win: 60 of 62 people found the following review helpful. Good but flawedBy A. AliCan't understand the unrestrained adulation some reviewers have given this book. Soltis can write very well - see for example 'Soviet Chess' which is a scholarly work, or see 'Confessions of a Chess Grandmaster'. The title being reviewed here is also one of his better efforts.The book explains the pragmatic realities of calculation very well indeed. A thoughtful reading of this book will enhance one's understanding of what to calculate, how to calculate, how far to calculate, and what positions deserve calculation. By implication, one's strength would improve.It's difficult to provide a synopsis of this book because, like Kotov, it's not coherently orgainised but is a compendium of practical wisdom concerning calculation. Chapters include 'Trees and how to build them', 'Rechecking' and 'The Practical Calculator' - all of importance to a player.I've given this four stars (and not five) for 3 reasons.