The Prediction and Observation of the 1997 July 18 Stellar Occultation by Triton: More Evidence for Distortion and Increasing Pressure in Triton’S Atmosphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur

Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, Francois Colas, Alain Klotz, Christophe Pellier, Jean-Marc Petit, Philippe Rousselot, et al. To cite this version: Olivier Mousis, Ricardo Hueso, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sylvain Bouley, Benoît Carry, et al.. Instru- mental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy. Experimental Astronomy, Springer Link, 2014, 38 (1-2), pp.91-191. 10.1007/s10686-014-9379-0. hal-00833466 HAL Id: hal-00833466 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00833466 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Instrumental Methods for Professional and Amateur Collaborations in Planetary Astronomy O. Mousis, R. Hueso, J.-P. Beaulieu, S. Bouley, B. Carry, F. Colas, A. Klotz, C. Pellier, J.-M. Petit, P. Rousselot, M. Ali-Dib, W. Beisker, M. Birlan, C. Buil, A. Delsanti, E. Frappa, H. B. Hammel, A.-C. Levasseur-Regourd, G. S. Orton, A. Sanchez-Lavega,´ A. Santerne, P. Tanga, J. Vaubaillon, B. Zanda, D. Baratoux, T. Bohm,¨ V. Boudon, A. Bouquet, L. Buzzi, J.-L. Dauvergne, A. -

Appulses of Jupiter and Saturn

IN ORIGINAL FORM PUBLISHED IN: arXiv:(side label) [physics.pop-ph] Sternzeit 46, No. 1+2 / 2021 (ISSN: 0721-8168) Date: 6th May 2021 Appulses of Jupiter and Saturn Joachim Gripp, Emil Khalisi Sternzeit e.V., Kiel and Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: gripp or khalisi ...[at]sternzeit-online[dot]de Abstract. The latest conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn occurred at an optical distance of 6 arc minutes on 21 December 2020. We re-analysed all encounters of these two planets between -1000 and +3000 CE, as the extraordinary ones (< 10′) take place near the line of nodes every 400 years. An occultation of their discs did not and will not happen within the historical time span of ±5,000 years around now. When viewed from Neptune though, there will be an occultation in 2046. Keywords: Jupiter-Saturn conjunction, Appulse, Trigon, Occultation. Introduction reason is due to Earth’s orbit: while Jupiter and Saturn are locked in a 5:2-mean motion resonance, the Earth does not The slowest naked-eye planets Jupiter and Saturn made an join in. For very long periods there could be some period- impressive encounter in December 2020. Their approaches icity, however, secular effects destroy a cycle, e.g. rotation have been termed “Great Conjunctions” in former times of the apsides and changes in eccentricity such that we are and they happen regularly every ≈20 years. Before the left with some kind of “semi-periodicity”. discovery of the outer ice giants these classical planets rendered the longest known cycle. The separation at the instant of conjunction varies up to 1 degree of arc, but the Close Encounters latest meeting was particularly tight since the planets stood Most pass-bys of Jupiter and Saturn are not very spectac- closer than at any other occasion for as long as 400 years. -

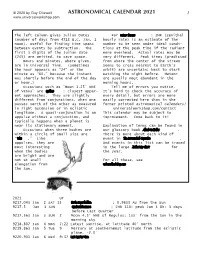

Astronomical Calendar 2021 1

© 2020 by Guy Ottewell ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR 2021 1 www.universalworkshop.com The left column gives Julian Dates For meteor showers: ZHR (zenithal (number of days from 4713 B.C. Jan. 1 hourly rate) is an estimate of the noon), useful for finding time spans number to be seen under ideal condi- between events by subtraction. The tions at the peak time if the radiant first 3 digits of the Julian date were overhead. Actual rates may be (245) are omitted, to save space. very different. Peak times (predicted Hours and minutes, where given, from where the center of the stream are in Universal Time. (Sometimes seems to cross nearest to Earth’s the hour appears as “24” or the orbit) are uncertain; best to start minute as “60,” because the instant watching the night before. Meteor was shortly before the end of the day are usually most abundant in the or hour.) morning hours. Occasions such as “Moon 1.25° NNE Tell me of errors you notice. of Venus” are appulses: closest appar- It’s hard to check the accuracy of ent approaches. They are slightly every detail, but errors are more different from conjunctions, when one easily corrected here than in the passes north of the other as measured former printed Astronomical Calendars! in right ascension or in ecliptic universalworkshop.com/contact longitude. A quasi-conjunction is an This calendar may be subject to appulse without a conjunction, and improvement. Come back to it! typically happens when a planet is near its stationary moment. Explanation of terms can be found in Occasions when three bodies are our glossary book Albedo to Zodiac. -

Glossary: Only Some Selected Terms Are Defined Here; for a Full Glossary

Glossary: Only some selected terms are defined here; for a full glossary consult an astronomical dictionary or google the word you need defined. Aphelion/Perihelion: Earth’s orbit is elliptical so the planet is farthest from the Sun at aphelion (first week of July) and closest at perihelion (first week of Jan). Apogee/Perigee: Since orbits around the Sun or Earth are usually ellipses, the farthest and nearest distances use “apo” (far) and “peri” (near) to describe the maximum and minimum values. For Earth and its satellites, apogee is the farthest point and perigee is the nearest (“geo” = Earth). The same prefixes are applied to orbits around the Moon -”luna” (apolune and perilune) Sun -”helios” (aphelion/perihelion), etc. Appulse: A close approach of two astronomical objects. i.e. minimum separation expressed in degrees, minutes and seconds of arc where 1 degree = 60 minutes and 1 minute = 60 seconds of arc. Note: the Moon and Sun are about 0.5 degrees or 30 minutes of arc across. Bolides or Fireballs: A very bright meteor (shooting star) that often can light up the ground and produce meteorites. See Meteor Shower below for more. Conjunction: The point in time when two stellar objects have the same Right Ascension. This is usually close to the minimum separation of the two objects but may not necessarily be minimum. (See also appulse above). When a planet is at Inferior Conjunction with the Sun it is between Earth and Sun and in Superior Conjunction, it is on the opposite side of the sun. At neither time are they easy (but not impossible) to see since they are near the Sun. -

Observer's Handbook 1974

the OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK 1974 sixty- sixth year of publication the ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY of CANADA THE ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA Incorporated 1890 Federally Incorporated 1968 The National Office of the Society is located at 252 College Street, Toronto 130, Ontario; the business office, reading room and astronomical library are housed here. Membership is open to anyone interested in astronomy and applicants may affiliate with one of the eighteen Centres across Canada established in St. John’s, Halifax, Quebec, Montreal, Ottawa, Kingston, Hamilton, Niagara Falls, London, Windsor, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Calgary, Vancouver, Victoria and Toronto, or join the National Society direct. Publications of the Society are free to members, and include the Jo u r n a l (6 issues per year) and the O bserver’s H a n d b o o k (published annually in November). Annual fees of $12.50 ($7.50 for full-time students) are payable October 1 and include the publications for the following calendar year. VISITING HOURS AT SOME CANADIAN OBSERVATORIES Burke-Gaffney Observatory, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. October-April: Saturday evenings 7:00 p.m. May-September: Saturday evenings 9:00 p.m. David Dunlap Observatory, Richmond Hill, Ontario. Wednesday mornings throughout the year, 10:00 a.m. Saturday evenings, April through October (by reservations, tel. 884-2112). Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, B.C. May-August: Daily, 9:15 a.m.-4:30 p.m. (Guide, Monday to Friday). Sept.-April: Monday to Friday, 9:15 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Public observing, Saturday evenings, April-October, inclusive. -

Glossary 2010 Ablation Erosion of an Object (Generally a Meteorite) by The

Glossary 2010 ablation erosion of an object (generally a meteorite) by the friction generated when it passes through the Earth’s atmosphere achromatic lens a compound lens whose elements differ in refractive constant in order to minimize chromatic aberration albedo the ratio of the amount of light reflected from a surface to the amount of incident light alignment the adjustment of an object in relation with other objects altitude the angular distance of a celestial body above or below the horizon appulse a penumbral eclipse of the Moon aphelion the point on its orbit where the Earth is farthest from the Sun arcminute one sixtieth of a degree of angular measure arcsecond one sixtieth of an arcminute, or 1/3600 of a degree ascending node in the orbit of a Solar System body, the point where the body crosses the ecliptic from south to north asteroid a small rocky body that orbits a star — in the Solar System, most asteroids lie between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter astronomical unit mean distance between the Earth and the Sun asynchronous in connection with orbital mechanics, refers to objects that pass overhead at different times of the day; does not move at the same speed as Earth’s rotation axis theoretical straight line through a celestial body, around which it rotates azimuth the direction of a celestial body from the observer, usually measured in degrees from north bandpass filter a device for suppressing unwanted frequencies without appreciably affecting the desired frequencies binary star two stars forming a physically bound pair -

Lunar Distances Final

A (NOT SO) BRIEF HISTORY OF LUNAR DISTANCES: LUNAR LONGITUDE DETERMINATION AT SEA BEFORE THE CHRONOMETER Richard de Grijs Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Balaclava Road, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract: Longitude determination at sea gained increasing commercial importance in the late Middle Ages, spawned by a commensurate increase in long-distance merchant shipping activity. Prior to the successful development of an accurate marine timepiece in the late-eighteenth century, marine navigators relied predominantly on the Moon for their time and longitude determinations. Lunar eclipses had been used for relative position determinations since Antiquity, but their rare occurrences precludes their routine use as reliable way markers. Measuring lunar distances, using the projected positions on the sky of the Moon and bright reference objects—the Sun or one or more bright stars—became the method of choice. It gained in profile and importance through the British Board of Longitude’s endorsement in 1765 of the establishment of a Nautical Almanac. Numerous ‘projectors’ jumped onto the bandwagon, leading to a proliferation of lunar ephemeris tables. Chronometers became both more affordable and more commonplace by the mid-nineteenth century, signaling the beginning of the end for the lunar distance method as a means to determine one’s longitude at sea. Keywords: lunar eclipses, lunar distance method, longitude determination, almanacs, ephemeris tables 1 THE MOON AS A RELIABLE GUIDE FOR NAVIGATION As European nations increasingly ventured beyond their home waters from the late Middle Ages onwards, developing the means to determine one’s position at sea, out of view of familiar shorelines, became an increasingly pressing problem. -

Observer's Handbook 1980

OBSERVER’S HANDBOOK 1980 EDITOR: JOHN R. PERCY ROYAL ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF CANADA CONTRIBUTORS AND ADVISORS A l a n H. B a t t e n , Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, Victoria, B.C., Canada V 8 X 3X3 (The Nearest Stars). Terence Dickinson, R.R. 3, Odessa, Ont., Canada K0H 2H0 (The Planets). M arie Fidler, Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 124 Merton St., Toronto, Ont., Canada M4S 2Z2 (Observatories and Planetariums). V ictor Gaizauskas, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, Ont., Canada K1A 0R6 (Sunspots). J o h n A. G a l t , Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Penticton, B.C., Canada V2A 6K3 (Radio Sources). Ian Halliday, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, Ont., Canada K1A 0R6 (Miscellaneous Astronomical Data). H e le n S. H o g g , David Dunlap Observatory, University of Toronto, Richmond Hill, Ont., Canada L4C 4Y6 (Foreword). D o n a l d A. M a c R a e , David Dunlap Observatory, University of Toronto, Richmond Hill, Ont., Canada L4C 4Y6 (The Brightest Stars). B r ia n G. M a r s d e n , Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, Mass., U.S.A. 02138 (Comets). Janet A. M attei, American Association o f Variable Star Observers, 187 Concord Ave., Cambridge, Mass. U.S.A. 02138 (Variable Stars). P e t e r M. M illm a n , Herzberg Institute o f Astrophysics, National Research Council, Ottawa, Ont., Canada K1A 0R6 (Meteors, Fireballs and Meteorites). A n t h o n y F. J. M o f f a t , D épartement de Physique, Université de Montréal, Montréal, P.Q., Canada H3C 3J7 (Star Clusters). -

Transits of Mercury, 1605–2999 CE

Appendix A Transits of Mercury, 1605–2999 CE Date (TT) Int. Offset Date (TT) Int. Offset Date (TT) Int. Offset 1605 Nov 01.84 7.0 −0.884 2065 Nov 11.84 3.5 +0.187 2542 May 17.36 9.5 −0.716 1615 May 03.42 9.5 +0.493 2078 Nov 14.57 13.0 +0.695 2545 Nov 18.57 3.5 +0.331 1618 Nov 04.57 3.5 −0.364 2085 Nov 07.57 7.0 −0.742 2558 Nov 21.31 13.0 +0.841 1628 May 05.73 9.5 −0.601 2095 May 08.88 9.5 +0.326 2565 Nov 14.31 7.0 −0.599 1631 Nov 07.31 3.5 +0.150 2098 Nov 10.31 3.5 −0.222 2575 May 15.34 9.5 +0.157 1644 Nov 09.04 13.0 +0.661 2108 May 12.18 9.5 −0.763 2578 Nov 17.04 3.5 −0.078 1651 Nov 03.04 7.0 −0.774 2111 Nov 14.04 3.5 +0.292 2588 May 17.64 9.5 −0.932 1661 May 03.70 9.5 +0.277 2124 Nov 15.77 13.0 +0.803 2591 Nov 19.77 3.5 +0.438 1664 Nov 04.77 3.5 −0.258 2131 Nov 09.77 7.0 −0.634 2604 Nov 22.51 13.0 +0.947 1674 May 07.01 9.5 −0.816 2141 May 10.16 9.5 +0.114 2608 May 13.34 3.5 +1.010 1677 Nov 07.51 3.5 +0.256 2144 Nov 11.50 3.5 −0.116 2611 Nov 16.50 3.5 −0.490 1690 Nov 10.24 13.0 +0.765 2154 May 13.46 9.5 −0.979 2621 May 16.62 9.5 −0.055 1697 Nov 03.24 7.0 −0.668 2157 Nov 14.24 3.5 +0.399 2624 Nov 18.24 3.5 +0.030 1707 May 05.98 9.5 +0.067 2170 Nov 16.97 13.0 +0.907 2637 Nov 20.97 13.0 +0.543 1710 Nov 06.97 3.5 −0.150 2174 May 08.15 3.5 +0.972 2644 Nov 13.96 7.0 −0.906 1723 Nov 09.71 13.0 +0.361 2177 Nov 09.97 3.5 −0.526 2654 May 14.61 9.5 +0.805 1736 Nov 11.44 13.0 +0.869 2187 May 11.44 9.5 −0.101 2657 Nov 16.70 3.5 −0.381 1740 May 02.96 3.5 +0.934 2190 Nov 12.70 3.5 −0.009 2667 May 17.89 9.5 −0.265 1743 Nov 05.44 3.5 −0.560 2203 Nov -

Almanac Skygazer's

Skygazer’s 40°N FOR LATITUDES AlmanacSGA 2017NEAR (North 40° NORTH America) EVENING MORNING A SUPPLEMENT TO SKY & TELESCOPE 5 p.m. 6 7 8 9 10 11 Midnight 1 220173 4 5 6 7 a.m. Sunset Set 7 Quadrantids 4 5 Y 7 8 9 Uranus P R Y Transits Rise A R 15 16 U A Sirius Rises 8 N U A A N 22 t 23 Equation J h Sunrise A g i of time l J i Julian day 2,457,000+ day Julian w 30 29 t Sirius Transits Neptune Sets g E Set n Polaris’s Upper Culmination i n 9 M 5 n d r 8 5 6 s o Y 7 Orion Nebula M42 Transits P e t m r R o Y e c f u A R e S 12 13 v r U A e y n U Pleiades Transit f R i Rise A R n Pollux Transits o R g s 10 B 20 19 i Jupiter Transits t u r s B E a e n Sun t E t F w e S s F slow i V 26 l Antares Rises 27 i g Saturn Rises h Set P t 5 11 6 3 1 8 EVENING SKY 12 13 H MORNING SKY H Lower Culmination of Polaris C C Rise Jan 1 Neptune 0.3° A R Jan 4 Earth is R A west of Mars 19 Uranus Sets 20 91,404,322 A 12 M miles from the Jan 11 Venus is 47° M Regulus Transits 27 east of the Sun 26 Sun (perihelion) P Set at 9 a.m. -

A Meta-Analysis of Coordinate Systems and Bibliography of Their Use on Pluto from Charon’S Discovery to the Present Day ⇑ Amanda Zangari

Icarus 246 (2015) 93–145 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus A meta-analysis of coordinate systems and bibliography of their use on Pluto from Charon’s discovery to the present day ⇑ Amanda Zangari Southwest Research Institute, 1050 Walnut St, Suite 300, Boulder, CO 80302, United States Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States article info abstract Article history: This paper aims to alleviate the confusion between many different ways of defining latitude and Received 21 January 2014 longitude on Pluto, as well as to help prevent future Pluto papers from drawing false conclusion due Revised 15 October 2014 to problems with coordinates. In its 2009 meeting report, the International Astronomical Union Working Accepted 21 October 2014 Group on Cartographic Coordinates and Rotational Elements redefined Pluto coordinates to follow a Available online 4 November 2014 right-handed system (Archinal, B.A., et al. [2011a]. Celest. Mech. Dynam. Astron. 109, 101–135; Archinal, B.A., et al. [2011b]. Celest. Mech. Dynam. Astron. 110, 401–403). However, before this system was Keywords: redefined, both the previous system (defining the north pole to be north of the invariable plane), and Pluto the ‘‘new’’ system (the right-hand rule system) were commonly used. A summary of major papers on Charon Pluto, surface Pluto and the system each paper used is given. Several inconsistencies have been found in the literature. The vast majority of papers and most maps use the right-hand rule, which is now the IAU system and the system recommended here for future papers. -

A Treatise on Astronomy Theoretical and Practical by Robert

NAPOLI Digitized by Google Digitized Google A TREATISE ov ASTRONOMY THEORETICAL and PRACTICAL. BY ROBERT WOODHOUSE, A M. F.R.S. FELLOW OF GONVILLK AND CAIUS COLLEGE, AND PLUMIAN PROFESSOR OF ASTRONOMY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE. Part II. Vol. I. CONTAINING THE THEORIES OF THE SUN, PLANETS, AND MOON. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED BY 3 . SMITH, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY ; FOR J. DEIGHTON & SONS, AND O. & W. B. WHITTAKER, LONDON. 1823 Digitized by Google Digitized by Google : ; —; CHAP. XVII. ON THE SOLAR THEORY Inequable Motions of the Sun in Right Ascension and Longi- tude.— The Obliquity of the Ecliptic determined from Ob- servations made near to the Solstices . — The Reduction of Zenith Distances near to the Solstices, to the Solstitial Zenith Distance.—Formula of such Reduction.—Its Application . Investigation of the Form of the Solar Orbit. — Kepler’s Discoveries.— The Computation of the relative Values of the Sun’s Distances and of the Angles described round the Earth.— The Solar Orbit an Ellipse. — The Objects of the Elliptical Theory. In giving a denomination to the preceding part of this Volume, we have stated it to contain the Theories of the fixed Stars such theories are, indeed, its essential subjects ; but they are not exclusively so. In several parts we have been obliged to encroach on, or to borrow from, the Solar Theory and, in so doing, have been obliged to establish certain points in that theory, or to act as if they had been established. To go no farther than the terms Right Ascension, Latitude, and Longitude. The right ascension of a star is measured from the first point of Aries, which is the technical denomination of the intersection of the equator and ecliptic, the latter term de- signating the plane of the Sun’s orbit the latitude of a star is its angular distance from the last mentioned plane ; and the longitude of a star is its distance from the first point of Aries measured along the ecliptic.