N March 2013, 140 Tuscarora Indians Traveled from Their Reservation Near

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Ogden Land Company

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 2-25-1897 Ogden Land Company. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Doc. No. 154, 54th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1897) This Senate Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 54TH CONGRESS,} SENATB. DocuMENT 2r7 Sess·ion. { No. 154. OGDEN LA~D COMPANY. FEBRUARY 25, 1897.-Laid on the table and ordered to be printed. Mr. O.A.LL presented the following MEMORIAL OF THE SENECA NATION OF INDIANS, PROTESTING AGAINST THE PROPOSED PURCHASE BY THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR OF THE TITLE OR INTEREST OF THE OGDEN LAND COMPANY, SO CALLED, IN' AND TO THE LANDS EMBRACED WITHIN THE AI,LEGANY AND CATTARAUGUS INDIAN RESER VATIONS, IN THE S 'TATE OF NEW YORK. EXECUTIVE DEP.A.RTMENT, SENECA N A'l'ION OF INDIANS, Salamanca,, N. Y., -----, 1897. Know all men by these presents: That the Seneca Nation of Indians in council assembled have duly made and appointed W. C. Hoag, A. L. Jimerson, Frank Patterson, W. W. Jimerson, and W. S. Kennedy to be our delegates to go to Washington, D. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Indian Law for Local Courts

NEW YORK STATE JUDICIAL INSTITUTE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Who is an Indian (and why do we need to care)? ................................... 1 2. Criminal Jurisdiction ............................................................................ 3 3. Tribal Police .......................................................................................... 6 4. Tribal Vehicle and Traffic ...................................................................... 7 5. State Law Enforcement ......................................................................... 8 6. Tribal Courts ........................................................................................ 9 Civil Jurisdiction (or “now you need to care”) ........................................... 11 Exhausting Tribal Exhaustion ............................................................... 11 Sovereign Immunity .............................................................................. 12 Full Faith and Credit ............................................................................ 13 7. Domestic Relations and Family Law .................................................... 16 Child Support ...................................................................................... 16 Marriage & Divorce ............................................................................... 17 8. Hunting and Fishing ........................................................................... 18 9. Cutting Edge on Resolving Jurisdictional Issues ................................. 20 New York State, -

Cave Post Offices Alabama, Arkansas, and Florida

Cave Post Offices in Alabama, Arkansas, and Florida by Thomas Lera American Spelean History Association Special Publication Number Four May 2018 The American Spelean History Association The American Spelean History Association (ASHA) is an internal organization of the National Speleological Society. It is devoted to the study, interpretation, and dissemination of information about spelean history, which includes folklore, legends, and historical facts about caves throughout the world and the people who are associated with them, their thoughts, philosophies, difficulties, tragedies, and triumphs. Membership: Membership in the Association is open to anyone who is interested in the history of man’s use of caves. Membership in the National Speleological Society is not required. The Journal of Spelean History is the Association’s primary publication and is mailed to all members. The Journal includes articles covering a wide variety of topics relating to man’s use of caves, including historical cave exploration and use, saltpeter and other mineral extraction, show cave development and history, and other related topics. It is the primary medium for conveying information and ideas within the caving history community. A cumulative Journal of Spelean History index is available on the Association’s Web site, www.cavehistory.org, and issues over five years old may be viewed and downloaded at no cost. Membership: ASHA membership (or subscription) cost $2.00 per Journal of Spelean History issue mailed to U.S. addresses. Checks should be made payable to “ASHA” and sent to the Treasurer (Robert Hoke, 6304 Kaybro St, Laurel MD 20707). Sorry, we cannot accept credit cards. Check the Association’s Web site for information on foreign membership. -

Table-12.Pdf

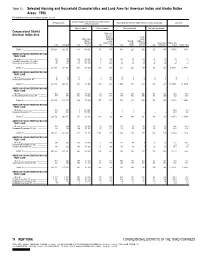

Table 12. Selected Housing and Household Characteristics and Land Area for American Indian and Alaska Native Areas: 1990 [For definitions of terms and meanings of symbols, see text] Occupied housing units with American Indian, Eskimo, All housing units or Aleut householder Households with American Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut householder Land area Owner occupied Renter occupied Family households Nonfamily households Congressional District Mean con- American Indian Area tract rent (dollars), Female Mean value specified house- (dollars), renter Married- holder, no specified paying cash couple husband Householder Square kilo- Total Occupied Total owner Total rent Total family present Total living alone meters Square miles ------------------------ District 1 239 124 192 807 313 139 800 176 637 364 224 109 125 105 1 650.6 637.3 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 219 180 139 95 800 13 400 108 72 24 44 44 3.6 1.4 Poospatuck Reservation, NY (state)-------- 46 45 29 175 200 2 313 23 13 6 8 8 .2 .1 Shinnecock Reservation, NY (state)-------- 173 135 110 86 100 11 458 85 59 18 36 36 3.4 1.3 ----------------------- District 23 243 283 211 591 264 63 700 234 286 331 228 77 167 128 15 504.1 5 986.1 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 Oneida (East) Reservation, NY------------ 20 1211–1363104421.2.1 ----------------------- District 24 261 036 202 380 934 46 900 489 264 1 055 734 234 368 291 32 097.8 12 393.0 AMERICAN INDIAN RESERVATION AND TRUST LAND All areas-------------------------- 754 634 561 45 000 64 184 485 342 106 140 124 49.2 19.0 St. -

Siege of Petersburg

Seige Of Petersburg June 9th 1864 - March 25th 1865 Siege Of Petersburg Butler”s assault (June 9) While Lee and Grant faced each other after Cold Harbor, Benjamin Butler became aware that Confederate troops had been moving north to reinforce Lee, leaving the defenses of Petersburg in a vulnerable state. Sensitive to his failure in the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, Butler sought to achieve a success to vindicate his generalship. He wrote, "the capture of Petersburg lay near my heart." Petersburg was protected by multiple lines of fortifications, the outermost of which was known as the Dimmock Line, a line of earthworks 10 miles (16 km) long, east of the city. The 2,500 Confederates stretched thin along this defensive line were commanded by a former Virginia governor, Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise. Butler”s plan was formulated on the afternoon of June 8, 1864, calling for three columns to cross the Appomattox and advance with 4,500 men. The first and second consisted of infantry from Maj. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore”s X Corps and U.S. Colored Troops from Brig. Gen. Edward W. Hinks”s 3rd Division of XVIII Corps, which would attack the Dimmock Line east of the city. The third was 1,300 cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. August Kautz, who would sweep around Petersburg and strike it from the southeast. The troops moved out on the night of June 8, but made poor progress. Eventually the infantry crossed by 3:40 a.m. on June 9 and by 7 a.m., both Gillmore and Hinks had encountered the enemy, but stopped at their fronts. -

Special Operations in the Civil War

From Raids to Recon: Special Operations in the Civil War John Dowdle (COL, USA RET) Company of Military Historians Gettysburg, PA April 20, 2013 Premise Were there missions conducted in the Civil War that would meet the modern definition and criteria of a successful Special Operations mission today? 2 Modern Definition of Special Operations A Special Operation is conducted by forces specially trained, equipped, and supported for a specific target whose destruction, elimination, or rescue (if hostages) is a political or military objective As defined by ADM William McRaven from his book, SPEC OPS: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare and Practice: 1995 3 Types of Modern Special Operations Types: • Unconventional Warfare (Guerrilla Warfare)* • Direct Action (Raids)* • Special Reconnaissance* • Foreign Internal Defense (FID) • Counter Terrorism • Coalition Warfare • Humanitarian/Civic Action (HCA) • Psychological Operations (Psyops) • Civil Affairs * Most common Civil War missions 4 Modern Special Operations Definitions . Unconventional Warfare - Military and paramilitary operations conducted in enemy-held, enemy-controlled , or politically sensitive territory. Includes guerilla warfare, evasion and escape, subversion, sabotage, and other operations of a covert or clandestine nature; normally of long-duration. Mainly conducted by indigenous forces organized, trained, equipped, supported, and directed in varying degrees by special operations forces . Direct Action - Overt or covert action against an enemy force. Seize, damage, or destroy a target; capture or recover personnel or material in support of strategic/operational objectives or conventional forces. Short-duration, small-scale offensive actions. Raids, ambushes, direct assault tactics; mine emplacement; standoff attacks by firing from air, ground, or maritime platforms; designate or illuminate targets for precision-guided munitions; support for cover and deception operations; or conduct independent sabotage normally inside enemy-held territory . -

Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission

Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Part II – Management Plan Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission July 2012 NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Part II - Management Plan Submitted to: The Niagara Falls National Heritage Area Commission U.S. National Park Service and Ken Salazar U.S. Secretary of the Interior Consulting team: John Milner Associates, Inc. Heritage Strategies, LLC National Trust for Historic Preservation Bergmann Associates July 2012 NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE A REA MANAGEMENT PLAN Part II – Implementation Plan ii NIAGARA FALLS NATIONAL HERITAGE A REA MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents PART II ─ MANAGEMENT PLAN CHAPTER 1 ─ CONCEPT AND APPROACH 1.1 What is a National Heritage Area? ................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Designation of the Niagara Falls National Heritage Area ................................ 1-2 1.3 Vision, Mission, and Goals of the National Heritage Area .............................. 1-3 1.4 The Heritage Area’s Preferred Alternative ....................................................... 1-4 1.5 National Signifi cance of the Heritage Area ......................................................1-6 1.6 The National Heritage Area Concept ............................................................... 1-8 1.6.1 Guiding Principles................................................................................... 1-8 1.6.2 Using the Management Plan ................................................................... 1-9 1.6.3 Terminology ............................................................................................1-9 -

A Draft Documentary History of the Cranberry Iron Mine in Mitchell County, North Carolina by Colonel (Ret.) William C

A Draft Documentary History of the Cranberry Iron Mine in Mitchell County, North Carolina By Colonel (Ret.) William C. Schneck, Jr. Corps of Engineers (As of 15 October 2017) Introduction This is a draft documentary history of the Cranberry Iron Mine, from the time that General Robert Hoke acquired the property in 1867 until the last active mining operation closed in the 1960s. I have attempted to collect relevant documents and place them in roughly chronological order. I have also included the available relevant technical information on the equipment used in the mine. Perhaps more can be accomplished on this portion of the subject. I invite other members of the Historical Society to add any missing material to this document and discuss/correct any deficient interpretations of the information at hand (particularly the dating of photos). As drafted, my intent was to focus on the mine (not the railroad, town, furnace in Johnson City, or other iron mining operations along the railroad as this document is currently over 200 pages). For those who wish to research the documents and photos further, I have provided links to expedite such attempts when available. In general, I have left the original spelling (sometimes autocorrect strikes, so I am unsure that all of it is original). I believe this documentary history will support much analysis (e.g. accurate structural drawings and detailed timelines of changes in the facilities), which will make it possible to develop more accurate modelling of this fascinating operation. I wish to thank Chris Ford for his assistance and encouragement to bring this document into a presentable state. -

Case Shot & Canister

Case Shot & Canister 1BA Publication of the Delaware Valley Civil War Round Table Partners with Manor College and the Civil War Institute Our 22nd Year February 2014 4BVolume 24 5BNumber 2 Editor Patricia Caldwell Contributors Hugh Boyle, Book Nook Editor Rose Boyle Mike Burkhimer Nancy Caldwell, Artistic Adviser Mike Cavanaugh Paula Gidjunis Ed Greenawald Bernice Kaplan Herb Kaufman Walt Lafty Jack Lieberman OUR ANNUAL CELEBRATION OF Jane Peters Estes Max Reihmann PRESIDENTS’ DAY Andy Waskie Sheryl Weiner Our February Meeting Original Photos Tuesday, February 18, 2014 Patricia Caldwell (unless 7:30 pm otherwise noted) 6:15 pm for dinner (all welcome - make reservations!) 3BUOfficers Radisson Hotel President Hugh Boyle Route 1 @ Old Lincoln Highway Vice President Trevose, PA Jerry Carrier Treasurer Herb Kaufman Secretary The Mary Lincoln Enigma Patricia Caldwell Presenter: Del Val Member Mike Burkhimer e-mail:[email protected] U phone: (215)638-4244 Dinner Menu – Grilled Sage Chicken, with Cabernet Demi-Glaze. website: HUwww.dvcwrt.orgU Served with soup du jour, rolls/butter, iced tea, soda, dessert. Substitute: Pasta (chef’s selection). Umailing addresses: for membership: 2601 Bonnie Lane Huntingdon Valley PA 19006 Call Rose Boyle at 215-638-4244 for reservations for newsletter items: by February 13. Dinner Price $24.00 3201 Longshore Avenue You are responsible for dinners not cancelled Philadelphia PA 19149-2025 by Monday morning February 17. In This Issue Membership renewal information Paula Gidjunis updates Preservation News What happened to our January meeting Civil War Institute Spring semester schedule Walt Lafty elaborates on a little-known event The Presidents’ Day theme in our Book Nook review by Mike Burkhimer Snow, Snow, Snow. -

Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1969-70

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 066 279 RC 006 405 AUTHOR Hathorn, John R. TITLE Annual Report of New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs, 1969-70. INSTITUTION New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Af f airs, Albany. PUB DATE 70 NOTE 33p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *American Indians; *Armual Reports; Committees; Community Health; Education; Educational Finance; Industry; Leadership; *Reservations (Indian); *Services; Social Services; *State Programs; Transportation IDENTIFIERS *New York State ABSTRACT . The 1969-70 annual report of the New York State Interdepartmental Committee on Indian Affairs describes the committee's purpose and function as being to render, through the several state departments and agencies represented, various services to the 8 Indian Reservations--Cattaraugus, St. Regis, Tonawanda, Tuscarora, Allegany, Anandaga, Shinnecock, and Poospatucklocated within the boundaries of New York. The Department of Commerce programs have included assistance in industrial development and tourist promotion. The Department of Education has contracted with 12 public school districts near the teservations to educate Indian children. In addition, transportation, tuition, and assistance to high school graduates enrcjlled in post-secondary institutions are discussed. The Department of Transportation maintains all highways on Indian Reservations, along with other state highways. The Department of Health offers general medical clinics, child health clinics, and non-clinic medical services, and county health departments of fer services in behalf of specific, reservations. The chairman's report of 1969-70 activities and events, addresses of the 7 New York State Interdepartmental Committee members and 21 Indian Interest Organizations, and 9 Indian Reservation leaders and officials are included.