The Lummi Nation -- WRIA 1 (Mountains to the Sea)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North: Lummi, Nooksack, Samish, Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish

Policy 7.01 Implementation Plan Region 2 North (R2N) Community Services Division (CSD) Serving the following Tribes: Lummi Nation, Nooksack Indian Tribe, Samish Indian Nation, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, Swinomish Tribal Community, Tulalip Tribes, & Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Biennium Timeframe: July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 Revised 04/2021 Annual Key Due Dates: April 1st - CSD Regional Administrators submit 7.01 Plan and Progress Reports (PPRs) to CSD HQ Coordinator. April 13th – CSD HQ Coordinator will submit Executive Summary & 7.01 PPRs to the ESA Office of Assistant Secretary for final review. April 23rd - ESA Office of the Assistant Secretary will send all 7.01 PPRs to Office of Indian Policy (OIP). 7.01 Meetings: January 17th- Cancelled due to inclement weather Next scheduled meeting April 17th, hosted by the Nooksack Indian Tribe. 07/07/20 Virtual 7.01 meeting. 10/16/20 7.01 Virtual meeting 01/15/21 7.01 Virtual 04/16/21 7.01 Virtual 07/16/21 7.01 Virtual Implementation Plan Progress Report Status Update for the Fiscal Year Goals/Objectives Activities Expected Outcome Lead Staff and Target Date Starting Last July 1 Revised 04/2021 Page 1 of 27 1. Work with tribes Lead Staff: to develop Denise Kelly 08/16/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by services, local [email protected] , Tulalip Tribes agreements, and DSHS/CSD Tribal Liaison Memorandums of 10/18/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by Understanding Dan Story, DSHS- Everett (MOUs) that best [email protected] meet the needs of Community Relations 01/17/2020 North 7.01 Meeting Region 2’s Administrator/CSD/ESA scheduled to be hosted by Upper Skagit American Indians. -

The Nooksack River: Floodplains That Work Phase 1

The Nooksack River: Floodplains That Work Phase 1 PROJECT BENEFITS Protect critical infrastructure: 2 water treatment plants 2 wastewater treatment plants 1 elementary school Reduce risk of loss of life & property: Building a resilient floodplain Mitigate debris flows Restore alluvial fan functions A community-driven approach to floodplain management Protect rural communities The Nooksack River: Floodplains That Work project uses an integrated approach to Protect valuable agricultural reduce flood hazards, improve habitat, and increase the resiliency of our rural lands communities and agriculture. The Whatcom County Flood Control Zone District is leading this effort, bringing diverse interests together to find solutions that work for Improve critical habitat: the community and achieve project goals. This project builds on improved relationships and trust built among multiple interests through the Lower Nooksack Restore riparian vegetation River Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan update process. Improve fish passage Project Components: Support salmon &Puget Ferndale Levee Improvement – Preliminary Design: reduce flood hazards Sound recovery for the City of Ferndale water and wastewater treatment plants and the Public Utility District No. 1 of Whatcom County water treatment facility; re-establish PROJECT PARTNERS riparian vegetation; improve recreational opportunities City of Ferndale Lynden Levee Improvement – Final Design and Construction: reduce flood hazards for the City of Lynden wastewater treatment plant, 500 -

Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits

PNNL-17161 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits Z Yang TP Khangaonkar December 2007 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

Changes in the Economy of the Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1969 Changes in the Economy of the Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington Don Newman Taylor Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, and the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Don Newman, "Changes in the Economy of the Lummi Indians of Northwest Washington" (1969). WWU Graduate School Collection. 918. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/918 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANGES IN THE ECONOMT OF THE LUMMI INDIANS OF NORTHWEST WASHINGTON A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Western Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Don Newman Taylor June, 1969 CHANGES IN THE ECONOMY OF THE LUMMI INDIANS OF NORTHWEST WASHINGTON by Don Newman Taylor Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Advisory Committee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is not long after embarking upon a study of this nature that one realizes but for the aid and cooperation of others, little would be accomplished. The number involved in this inquiry seem legion—to the point that the author, upon reflection, feels he has been little more than a compiler of data and ideas emanating from other sources, Althou^ it is impossible to name all concerned here, the author wishes to thank those who have assisted in this investigation. -

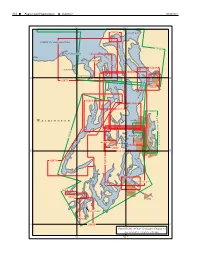

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

Stratigraphy and Chronology of Raised Marine Terraces, Bay View Ridge, Skagit County, Washington Robert T

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 1978 Stratigraphy and Chronology of Raised Marine Terraces, Bay View Ridge, Skagit County, Washington Robert T. Siegfried Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Siegfried, Robert T., "Stratigraphy and Chronology of Raised Marine Terraces, Bay View Ridge, Skagit County, Washington" (1978). WWU Graduate School Collection. 788. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/788 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Bellingham, Washington 98225 • [206] 676-3000 MASTER'S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree at Western Washington University, I agree that the Library shall make its copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying" of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes, or for financial gain, shall not be allowed without my written permission. 7 7 Robert T. Siegfried MASTER'S THESIS In presenting thisthesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements fora master's degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronicformat, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. -

Chapter 2 Setting

Chapter 2: Community Setting Many of the core characteristics and values that bring 2.1 Location, Topography and Temperature residents, businesses Bellingham is located in northwest Washington on the shore of and visitors to Bellingham Bay. The south and east boundaries of the urban area abut the slopes of Stewart, Lookout, and Chuckanut Bellingham lie in the Mountains, at the edge of the Cascade foothills that frame Mount vast natural Baker. resources within and surrounding the city. Topography ranges from sea level to about 500 feet above Puget Sound on the hilltops around Bellingham. Elevation increases to 3,050 feet at the top of Stewart Mountain, and eventually to 10,785 at the top of Mount Baker. The landform is generally flat to rolling within the urban growth area, though the plateau edge overlooking Bellingham Bay can drop off abruptly in slopes ranging from 40% to 75%. Mean temperatures vary from a high of 73 degrees in July to a low of 31 degrees Fahrenheit in January. Average annual precipitation is about 35 inches. Approximately 80% of the precipitation occurs from October through March with less than 6% falling during the summer months. Following is a list of environmental features that are found in and around the Bellingham Urban Area. 2.2 Water 2.2.1 Creeks Three major creeks and three minor ones drain the Bellingham area. These are: • Squalicum Creek – A major creek that starts in the Nooksack Valley and flows southwest to the mouth of Bellingham Bay. • Whatcom Creek – A major creek that drains from the northwest end of Lake Whatcom west into Bellingham Bay. -

1855 Treaty of Point Elliott

Treaty of Point Elliott, 1855 Articles of agreement and convention made and concluded at Muckl-te-oh, or Point Elliott, in the territory of Washington, this twenty-second day of January, eighteen hundred and fifty-five, by Isaac I. Stevens, governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for the saidTerritory, on the part of the United States, and the undersigned chiefs, head-men and delegates of the Dwamish, Suquamish, Sk-kahl-mish, Sam-ahmish, Smalh-kamish, Skope-ahmish, St-kah-mish, Snoqualmoo, Skai-wha-mish, N'Quentl-ma-mish, Sk-tah-le-jum, Stoluck-wha-mish, Sno-ho-mish, Skagit, Kik-i-allus, Swin-a-mish, Squin-ah-mish, Sah-ku- mehu, Noo-wha-ha, Nook-wa-chah-mish, Mee-see-qua-guilch, Cho-bah-ah-bish, and othe allied and subordinate tribes and bands of Indians occupying certain lands situated in said Territory of Washington, on behalf of said tribes, and duly authorized by them. ARTICLE 1. The said tribes and bands of Indians hereby cede, relinquish, and convey to the United States all their right, title, and interest in and to the lands and country occupied by them, bounded and described as follows: Commencing at a point on the eastern side of Admiralty Inlet, known as Point Pully, about midway between Commencement and Elliott Bays; thence eastwardly, running along the north line of lands heretofore ceded to the United States by the Nisqually, Puyallup, and other Indians, to the summit of the Cascade range of mountains; thence northwardly, following the summit of said range to the 49th parallel of north latitude; thence west, along said -

Preliminary Geologic Map of the Mount Baker 30- by 60-Minute Quadrangle, Washington

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Preliminary Geologic Map of the Mount Baker 30- by 60-Minute Quadrangle, Washington by R.W. Tabor1 , R.A. Haugerud2, D.B. Booth3, and E.H. Brown4 Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources, Olympia, Washington, 98504 OPEN FILE REPORT 94-403 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S.Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. iu.S.G.S., Menlo Park, California 94025 2U.S.G.S., University of Washington, AJ-20, Seattle, Washington 98195 3SWMD, King County Department of Public Works, Seattle, Washington, 98104 ^Department of Geology, Western Washington University, Bellingham, Washington 98225 INTRODUCTION The Mount Baker 30- by 60-minute quadrangle encompasses rocks and structures that represent the essence of North Cascade geology. The quadrangle is mostly rugged and remote and includes much of the North Cascade National Park and several dedicated Wilderness areas managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Geologic exploration has been slow and difficult. In 1858 George Gibbs (1874) ascended the Skagit River part way to begin the geographic and geologic exploration of the North Cascades. In 1901, Reginald Daly (1912) surveyed the 49th parallel along the Canadian side of the border, and George Smith and Frank Calkins (1904) surveyed the United States' side. Daly's exhaustive report was the first attempt to synthesize what has become an extremely complicated geologic story. -

The Tribes of Washington State Map Download

12 8 28 17 26 6 9 18 24 2 7 27 5 15 13 22 4 25 There are 29 federally-recognized Native American tribes 21 located on reservations throughout Washington state. 16 Each tribe has a body of elected officials that oversees its 20 governmental programs. They provide services including 14 health care, education, housing, public safety, courts, 10 transportation, natural resources, environment, culture 23 and economic development. Gaming revenue is a major source of funding to pay for tribal government services. 11 Tribes are investing in new initiatives to diversify their economic base. Investments range from hotels to golf 1 courses to shopping centers. 19 Tribes employ more than 30,000 people statewide and pay more than $1.5 billion annually in wages and benefits. Capital spending, and the purchase of goods and services from private companies, adds billions more dollars to the state’s economy each year. Tribal economic activities also generate millions of dollars in federal, state and local taxes. 29 Washingtontribes.org is a public education program of the Washington Indian Gaming Association. washingtontribes.org 3 1. Chehalis The Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis 4. Hoh The Hoh Tribe has 443 acres of 7. Lower Elwha Klallam The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe is located on roughly 11. Nisqually The Nisqually Indian Tribe has more 14. Puyallup The Puyallup Tribe of Indians has more than 4,000 members and is 18. Sauk-Suiattle The Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe is located near Darrington and 22. Spokane The Spokane Tribe of Indians’ reservation is 159,000 acres located 26. -

Wiser Lake Creek-Nooksack River Watershed

NRCS National Water Quality Initiative (NWQI) Watershed Assessment: Wiser Lake Creek-Nooksack River Watershed Prepared By: Whatcom Conservation District Lynden, WA December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2 Tables and Figures .......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Background and Purpose ..................................................................................................... 7 Background ...................................................................................................................... 7 Location of Watershed Assessment Area ......................................................................... 8 Sub-basins of Wiser Watershed ............................................................................................... 9 Special Districts ....................................................................................................................... 9 Water Quality Resource Concerns ................................................................................. 11 Washington State Surface Water Quality Criteria ................................................................. 11 303d Assessed Waters .......................................................................................................... -

Tribes in the Pacific Northwest Region

Tribes in the Pacific Northwest Region Tribe Full Name Tribe Alternate Name Tribe Contact Information Phone Web Site Burns Paiute Tribe Burns Paiute 100 Pasigo Street (541) 573-2088 http://www.burnspaiute-nsn.gov Burns, OR 97720-2442 Coeur D'Alene Tribe Coeur D'Alene P.O. Box 408 (208) 686-1800 http://www.cdatribe-nsn.gov/ 850 A Street Plummer, ID 83851-0408 Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes of Confederated Salish P.O. Box 278 (406) 675-2700 http://www.cskt.org the Flathead Reservation 42487 Complex Boulevard Pablo, MT 59855-0278 Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Confederated Yakama P.O. Box 151 (509) 865-5121 http://www.yakamanation-nsn.gov Yakama Nation 401 Fort Road Toppenish, WA 98948-0151 Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Confederated Coos 1245 Fulton Avenue (541) 888-9577 http://www.ctclusi.org Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians Coos Bay, OR 97420 Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians of Siletz Tribe P.O. Box 549 (541) 444-2532 http://www.ctsi.nsn.us Oregon 201 SE Swan Avenue Siletz, OR 97380-0549 Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Chehalis P.O. Box 536 (360) 273-5911 http://www.chehalistribe.org Reservation 420 Howanut Road Oakville, WA 98568 Confederated Tribes of the Colville Confederated Colville P.O. Box 150 (509) 634-2200 http://www.colvilletribes.com Reservation 1 Colville Street Nespelem, WA 99155-0150 Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Grand Ronde Grand Ronde Tribes 9615 Grand Ronde Road (503) 879-5211 http://www.grandronde.org Community of Oregon Grand Ronde, OR 97347-9712 Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Umatilla Tribe Nixyaawii Governance Center46411 (541) 276-3165 http://www.umatilla.nsn.us Indian Reservation Ti'míne Way Pendleton, OR 97801-0638 Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Warms Springs Tribe P.O.