Satellite Home Viewer Extension and Reauthorization Act Section 109 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glenn Reitmeier Component Digital Video Interface Now by the Time Testing Was Completed, All Used Worldwide

IGNITING CHANGE of a job that would allow Reitmeier to ing would determine the winner. Sarnoff “y I can’t sa enough apply advanced signal processing to TV. couldn’t pass up the challenge. Sarnoff also would send him to the Uni- An early prophet of digital TV, about the personal versity of Pennsylvania for his master’s. Reitmeier was tapped to lead the devel- attention of the Villanovans contributing to the community Reitmeier hit the ground digitizing. He opment of the Advanced Digital HDTV helped develop the architecture and soft- system for Sarnoff and its consortium faculty and their ware for one of the first computer systems partners: Philips, Thomson and NBC. dedication to for digitizing video; picked up his first pat- Competing against the calendar and new ent for picture resizing for digital video digital approaches from such titans as teaching.” effects; and contributed to experiments AT&T and MIT, Reitmeier’s team worked that led to the adoption of a standard for feverishly to build their prototype. — Glenn Reitmeier component digital video interface now By the time testing was completed, all used worldwide. This pace never slack- analog proposals had been eliminated, ened in Reitmeier’s 25 years at Sarnoff. since they couldn’t send HDTV in a single His collaboration and leadership in digi- over-the-air TV channel. But surprisingly, Their achievement earned the Grand tal video research, consumer electronics none of the four digital entries was victori- Alliance companies an Emmy Award. and other technologies earned Reitmeier ous. Each had strengths and weaknesses. Since 2002, Reitmeier has guided NBC the industry’s respect—and his children’s. -

Are You What You Watch?

Are You What You Watch? Tracking the Political Divide Through TV Preferences By Johanna Blakley, PhD; Erica Watson-Currie, PhD; Hee-Sung Shin, PhD; Laurie Trotta Valenti, PhD; Camille Saucier, MA; and Heidi Boisvert, PhD About The Norman Lear Center is a nonpartisan research and public policy center that studies the social, political, economic and cultural impact of entertainment on the world. The Lear Center translates its findings into action through testimony, journalism, strategic research and innovative public outreach campaigns. Through scholarship and research; through its conferences, public events and publications; and in its attempts to illuminate and repair the world, the Lear Center works to be at the forefront of discussion and practice in the field. futurePerfect Lab is a creative services agency and think tank exclusively for non-profits, cultural and educational institutions. We harness the power of pop culture for social good. We work in creative partnership with non-profits to engineer their social messages for mass appeal. Using integrated media strategies informed by neuroscience, we design playful experiences and participatory tools that provoke audiences and amplify our clients’ vision for a better future. At the Lear Center’s Media Impact Project, we study the impact of news and entertainment on viewers. Our goal is to prove that media matters, and to improve the quality of media to serve the public good. We partner with media makers and funders to create and conduct program evaluation, develop and test research hypotheses, and publish and promote thought leadership on the role of media in social change. Are You What You Watch? is made possible in part by support from the Pop Culture Collaborative, a philanthropic resource that uses grantmaking, convening, narrative strategy, and research to transform the narrative landscape around people of color, immigrants, refugees, Muslims and Native people – especially those who are women, queer, transgender and/or disabled. -

WILE MOTORS WE HAVE 8 Hatchback Sport Coupe New Carpeting, Great $5,000 After a Judge Noted He Had Location, Wolking Dis New *8380"" Shown No Remorse

fr ?4 — MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, Jan. 13. 1989 APARTMENTS Merchandise I MISCELLANEOUS CARS (FOR RENT FOR SALE FOR SALE EAST HARTFORD. EIGHT month old water- 1980 FORD. Fairmont. Clean, second floor, 5 1 Spcciolisj^j bed, $325. Courthouse Four cylinder, four rooms, 2 bedrooms. I FURNITURE One Gold membership, speed. Runs and looks J Stove and refrigerator. 12'/2 months left tor good. Asking $500. 649- Security required. $650 5434. PORTABLE twin bed. ■^BOOKKEEPING/ $450. Compared to rep- plus utilities. Coll 644- Like new. Includes ■^CARPENTRY/ ■^HEATING/ MISCELLANEOUS ulor price of $700 plus. 1984 MERCURY Marquis. 1712.________________ mattress. $75. 643-8208. E ^ income tax 1 2 ^ REMODELING IS H J PLUMBING SERVICES Eric 649-3426.D One owner. Excellent TWO bedroom with heat condition. 39,000 miles. A on first floor. $600 per I FUEL OIL/COAL/ Fully equipped. $5395. SA5 HOME GSL Building Mainte 633-2824. month. No pets. One Ifirew ooo 1 9 8 8 INCOME TAXES PJ’s Plumblna, Heating 8 nance Co. Commercl- Automotive months security. Coll IMPR0VEMENT5 1984 RENAULT Encore. Consultation / Preparation & REPAIRS Air Conditioning al/ResIdentlal building Don, 643-2226, leoye SEA SO N ED firewood for Boilers, pumps, hot water repairs and home Im Five door, five speed. message. After 7pm, Individuals / "No Job Too Small" tanks, new and air conditioning, body sale. Cut, split and Regleleted and FuSy Insured provements. Interior 646-9892.____________ delivered. $35 per laad. Sole Proprietors replacements, and exterior painting, excellent, new muffler, MANCHESTER. Two 742-1182. FREE ESTIMATES FREE ESTIMATES light carpentry. Com I0 F O R S A L E tires. -

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: a MEDIUM in SEARCH of SOLUTIONS John W

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: A MEDIUM IN SEARCH OF SOLUTIONS JoHN W. MACY, JR.* INTRODUCTION In its simplest and most comprehensive definition, a communications system is a process in which creative communicators become aware of the expressed and some- times unexpressed needs of the users of the system and responsively collect and provide information, entertainment, and other resources toward the satisfaction of these needs. Despite the often quoted and now popular belief that in electronic com- munications systems "the medium is the message,"' the design of a system in which the message is itself the message-and the medium is merely a means of delivering a diversity of messages of intrinsic value to the users-is a mandate for radio and television in the decade of the 1970s. This is one of the basic philosophies behind the approach of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as it builds and develops the public sector of broadcasting. Some time ago Robert Oppenheimer was quoted as saying, "What is new is new not because it has never been there before, but because it has changed in quality."2 This is surely what is new about the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. But to understand the nature and direction of the qualitative changes brought about by its creation and activities, it is necessary to look first at what was there before and how the Corporation came into being. I BACKGROUND OF PUBLIC BROADCASTING Over the past fifty years, the American public, through its elected representatives and otherwise, has made a series of choices to encourage the development of a public alternative in the field of communications. -

Magisterarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit „Es war einmal MTV. Vom Musiksender zum Lifestylesender. Eine Programmanalyse von MTV Germany im Jahr 2009.“ Verfasserin Sandra Kuni, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, Februar 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 841 Studienichtung lt. Studienblatt: Publizistik und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hausjell DANKSAGUNG Die Fertigstellung der Magisterarbeit bedeutet das Ende eines Lebensabschnitts und wäre ohne die Hilfe einiger Personen nicht so leicht möglich gewesen. Zu Beginn möchte ich Prof. Dr. Fritz Hausjell für seine kompetente Betreuung und die interessanten und vielseitigen Gespräche über mein Thema danken. Großer Dank gilt Dr. Axel Schmidt, der sich die Zeit genommen hat, meine Fragen zu bearbeiten und ein informatives Experteninterview per Telefon zu führen. Besonders möchte ich auch meinem Freund Lukas danken, der mir bei allen formalen und computertechnischen Problemen geholfen hat, die ich alleine nicht geschafft hätte. Meine Tante Birgit stand mir immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite, ihr möchte ich für das Korrekturlesen meiner Arbeit und ihre Verbesserungsvorschläge danken. Zum Schluss danke ich noch meinen Eltern und all meinen guten Freunden für ihr offenes Ohr und ihre Unterstützung. Danke Vicky, Kathi, Pia, Meli und Alex! EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich habe diese Magisterarbeit selbständig verfasst, alle meine Quellen und Hilfsmittel angegeben und keine unerlaubten Hilfen eingesetzt. Diese Arbeit wurde bisher in keiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt. Ort und Datum Sandra Kuni INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. EINLEITUNG .....................................................................................................1 I.1. Auswahl der Thematik................................................................................................ 1 I.2. -

NCA All-Star National Championship Wall of Fame

WALL OF FAME DIVISION YEAR TEAM CITY, STATE L1 Tiny 2019 Cheer Force Arkansas Tiny Talons Conway, AR 2018 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2017 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2016 The Stingray All Stars Grape Marietta, GA 2015 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2014 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Plano, TX 2013 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2012 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2011 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2010 Texas Lonestar Cheer Company Houston, TX 2009 Cheer Athletics Itty Bitty Kitties Dallas, TX 2008 Woodlands Elite The Woodlands, TX 2007 The Pride Addison, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep D2 2019 East Texas Twisters Ice Ice Baby Canton, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1.1 Tiny Prep 2019 All-Star Revolution Bullets Webster, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Tiny Prep 2018 Liberty Cheer Starlettes Midlothian, TX 2017 Louisiana Rebel All Stars Faith (A) Shreveport, LA Cheer It Up All-Stars Pearls (B) Tahlequah, OK 2016 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2015 Texas Legacy Cheer Laredo, TX 2014 Raider Xtreme Raider Tots Lubbock, TX __________________________________________________________________________________________________ L1 Mini 2008 The Stingray All Stars Marietta, GA 2007 Odyssey Cheer and Athletics Arlington, TX 2006 Infinity Sports Kemah, -

47Th Annual New York Emmy® Awards

THE 47th ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY AWARDS – 2004 WINNERS SINGLE NEWSCAST: Under 35 minutes CBS 2 News at 11: City Hall Shooting. July 23, 2003. (WCBS-TV Channel 2). Kristin Quillinan, Executive Producer; Gerard Andrews, Producer; Ernie Anastos, Dana Tyler, Anchors; Richard Bamberger, Assignment Manager; Paul Zucker, Director. SINGLE NEWSCAST: Over 35 minutes FOX 5 NEWS AT 10 PM. May 20, 2003. (WNYW FOX 5). Michelle Donovan, Producer; Joseph Farrington, Assignment Editor; Peter Pontillo, Director; Rosanna Scotto, Len Cannon, Anchors. SINGLE MORNING NEWS PROGRAM Good Day New York. February 6, 2003. (WNYW FOX 5). David Shenfeld, Executive Producer; Adrienne Paxton, Producer; Tommy Simpson, Director; Rosanna Scotto, Anchor. COVERAGE OF AN INSTANT BREAKING NEWS STORY NYC Blackout. August 14, 2003. (WCBS-TV Channel 2). Philip O’Brien, Assistant News Director; Maura McHugh, Kristin Quillinan, Executive Producers; John Verrilli, Managing Editor; Richard Bamberger, Assignment Manager; Brian Lowder, Andrew Friedman, Wanda Prisanzano, Assignment Editors; Ernie Anastos, Dana Tyler, Anchors; Jeffrey Gesoff, Gerard Andrews, Kelly Drossel, Mindy Bloom, Emad Asghar, Producers; David Diaz, Hazel Sanchez, Andrew Kirtzman, Marcia Kramer, Robert Strang, Brendan Keefe, Lisa Daniels, Jay Dow, Louis Young, Joseph Biermann, John Slattery, Morry Alter, Mary Calvi, Reporters; Susan King, Director. COVERAGE OF AN ANTICIPATED NEWS STORY Air 11 Remembers 9/11. September 11, 2002. (WPIX-TV). Melinda Murphy, Reporter; Jennifer Larned, Chet Wilson, Ray Rivera, Segment Producers. COVERAGE OF A CONTINUING NEWS STORY Journey of Hope. May 19, 20, 2003. (News 12 Long Island). Michael DelGiudice, Photojournalist, Editor, Producer; Elizabeth Hashagen, Producer. SINGLE HARD NEWS STORY Vietnam. October 31, 2002. (WNBC-TV). Chuck Scarborough, Reporter; Steve Narisi, Producer. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

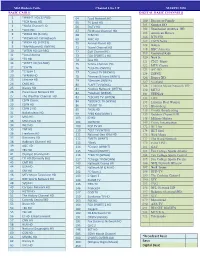

Thinkbright Programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009

ThinkBright programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009 So what is ThinkBright? A Community Asset. / À} Ì vi} i>À} à > v>Þ v `}Ì> i>À} ÃiÀÛVið / i ÃiÀÛVi Ì>À}iÌà ÃÌÕ`iÌÃ] i`ÕV>ÌÀÃ] v>iÃ] >` i>ÀiÀà v > >}ið / i / À} Ì ÃÕÌi v ÃiÀÛVià VÕ`iÃ\ ThinkBright TV ThinkBright Online Special TV and Outreach Initiatives Professional Development for Teachers ThinkBright TV. / à `}Ì> V >i Ài`ivià i>À} vÀ «i«i v > >}ið Ì vviÀà > Ü`i Û>ÀiÌÞ v «À}À>} Ì i`ÕV>Ìi] i} Ìi] >` iÀV ÕÀ VÕÌÞ >` LiÞ`° 7 iÌ iÀ ÞÕ½Ài } vÀ V `Ài½Ã «À}À>Ã] «À}À>Ã Ì ÕÃi ÞÕÀ V>ÃÃÀ] Ài>Ìi` VÌiÌ] À iÀV } iÌiÀÌ>iÌ / À} Ì /6 à vÀ ÞÕ° *ÕÃ] i>V iÛi} / À} Ì vi>ÌÕÀià > `i`V>Ìi` Ì ii Ã Ì >Ì LÕÃÞ ÛiÜiÀÃ Ü ÕÃÌ Ü i Ì tune in to find compelling programs that suit their interests! THEME NIGHTS Sundays / Family & Education 8/&% Mondays / Health & Wellness Tuesdays / Arts & Performance Wednesdays / History & Biography Thursdays / Heritage & Diversity Fridays / Think Globally Saturdays / Science & Nature ThinkBright Online. ÕÀÕà ÌiiÛà ÛiÜiÀà V> v` > ÌÀi>ÃÕÀi ÌÀÛi v iÀV iÌ ÀiÃÕÀVià vÀ ÃV ] i] >` VÕÌÞ ÕÃi° iV ÕÌ / À} ̽à /6 ÃV i`Õi] `i«Ì vÀ>Ì ÃiiVÌ «À}À>Ã] ÌiÀ>VÌÛi >VÌÛÌià >` }>iÃ] ÃÌ>`>À`ÃL>Ãi` iÃà «>Ã] `6`i "i] * - /i>V iÀi 9] }Ài>Ì vÀ>Ì Ã] >` Àit ThinkBright Brings Learning to Light! i>À Ài >Ì ÜÜÜ°/ À} Ì°À} À >``Ì> V«ià v Ì Ã }Õ`i] «i>Ãi VÌ>VÌ iÌÃÞ >ÛÀÃi >Ì Ç£È°n{x°Çäää iÝÌ° Î{x° ThinkBright is made possible through the support of our partners: New York State Music Fund ThinkBright is a service of The Western New York Public Broadcasting Association U Àâà *>â> U *ÃÌ "vvVi Ý £ÓÈÎ U Õvv>] iÜ 9À £{Ó{ä U ǣȰn{x°Çäää ThinkBright programming on Time Warner 21 / Digital 17.3 JANUARY & FEBRUARY 2009 ~~ Workout Series ~~ Classical Stretch Every Sunday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday morning at 6:00 am An effective total body workout of graceful movements which unlocks uncomfortably rigid muscles for a more flexible, relaxed and strengthened body. -

2020 March Channel Line up with Pricing Color

B is Mid-Hudson Cable Channel Line UP MARCH 2020 BASIC CABLE DIGITAL BASIC CHANNELS 2 *WMHT HD (17 PBS) 64 Food Network HD 100 Discovery Family 3 *FOX News HD 65 TV Land HD 101 Science HD 4 *NASA Channel HD 66 TruTV HD 102 Destination America HD 5 *QVC HD 67 FX Movie Channe l HD 105 American Heroes 6 *WRGB HD (6-CBS) 68 TCM HD 106 BTN HD 7 *WCWN HD CW Network 69 AMC HD 107 ESPN News 8 *WXXA HD (FOX23) 70 Animal Planet HD 108 Babytv 9 *My4AlbanyHD (WNYA) 71 Travel Channel HD 118 BBC America 10 *WTEN HD (10-ABC) 72 Golf Channel HD 119 Universal Kids 11 *Local Access 73 FOX SPORTS 1 HD 12 *FX HD 120 Nick Jr. 74 fuse HD 121 CMT Music 13 *WNYT HD (13-NBC) 75 Tennis Channel HD 122 MTV Classic 17 *EWTN 76 *LIGHTtv (WNYA) 123 IFC HD 19 *C-Span 1 77 *Comet TV (WCWN) 124 ESPNU 20 *WRNN HD 78 *Heroes & Icons (WNYT) 126 Disney XD 23 Lifetime HD 79 *Decades (WNYA) 127 Viceland 24 CNBC HD 80 *LAFF TV (WXXA) 128 Lifetime Movie Network HD 25 Disney HD 81 *Justice Network (WTEN) 130 MTV2 26 Paramount Network HD 82 *Stadium (WRGB) 131 TEENick 27 The Weather Channel HD 83 *ESCAPE TV (WTEN) 132 LIFE 28 ESPN Classic 84 *BOUNCE TV (WXXA) 133 Lifetime Real Women 29 ESPN HD 86 *START TV 135 Bloomberg 30 ESPN 2 HD 95 *HSN HD 138 Trinity Broadcasting 31 Nickelodeon HD 99 *PBS Kids(WMHT) 139 Outdoor Channel HD 32 MSG HD 103 ID HD 148 Military History 33 MSG PLUS HD 104 OWN HD 149 Crime Investigation 34 WE! HD 109 POP TV HD 172 BET her 35 TNT HD 110 *GET TV (WTEN) 174 BET Soul 36 Freeform HD 111 National Geo Wild HD 175 Nick Music 37 Discovery HD 112 *METV (WNYT) -

AGE Qualitative Summary

AGE Qualitative Summary Age Gender Race 16 Male White (not Hispanic) 16 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 17 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 18 Malel Blacklk or Africanf American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Female Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female White (p(not Hispanic)) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female Other 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 20 Female White (not Hispanic) 20 Female Other 20 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 20 Male Other 20 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 21 Female Don’t want to respond 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 21 Female White (not -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 103/Thursday, May 28, 2020

32256 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 103 / Thursday, May 28, 2020 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS closes-headquarters-open-window-and- presentation of data or arguments COMMISSION changes-hand-delivery-policy. already reflected in the presenter’s 7. During the time the Commission’s written comments, memoranda, or other 47 CFR Part 1 building is closed to the general public filings in the proceeding, the presenter [MD Docket Nos. 19–105; MD Docket Nos. and until further notice, if more than may provide citations to such data or 20–105; FCC 20–64; FRS 16780] one docket or rulemaking number arguments in his or her prior comments, appears in the caption of a proceeding, memoranda, or other filings (specifying Assessment and Collection of paper filers need not submit two the relevant page and/or paragraph Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2020. additional copies for each additional numbers where such data or arguments docket or rulemaking number; an can be found) in lieu of summarizing AGENCY: Federal Communications original and one copy are sufficient. them in the memorandum. Documents Commission. For detailed instructions for shown or given to Commission staff ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. submitting comments and additional during ex parte meetings are deemed to be written ex parte presentations and SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal information on the rulemaking process, must be filed consistent with section Communications Commission see the SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In (Commission) seeks comment on several section of this document. proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) proposals that will impact FY 2020 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: of the Commission’s rules or for which regulatory fees.