Two Stories from the Day I Was Born

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Integrated Annual Corporate Governance Report

Secutitieg aner Exchonge NIsvto Commission @\ SEC FORM _ I-ACGR INTEGRATED ANNUAT CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT t. For the fiscal year ended: December 3 1. 20 1 7 2. SEC Identification Number: PW-686 3. BIR Tax Identification No.: 000-263-340 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter: PHILIPPINE BANK 0F COMMUNICATIONS 5, Philippines (SEC Use Only) Province, Country or otherjurisdiction of Industrv Classification Code: incorporation or organization 7, 7226 Address ofprincipal office Postal Code 8, 830-7000 Issuer's telephone number, including area code 9. NA Former name, former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report. * SEC Form - I-ACGR Uodated 21,Dec2OI7 Page 3 of 80 INTEGRATED ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT RECOMMENDED CG COMPLIANT ADDITIONAL INFORMATION EXPLANATION PRACTICE/POLICY / NON- COMPLIANT The Board’s Governance Responsibilities Principle 1: The company should be headed by a competent, working board to foster the long- term success of the corporation, and to sustain its competitiveness and profitability in a manner consistent with its corporate objectives and the long- term best interests of its shareholders and other stakeholders. Recommendation 1.1 1. Board is composed of directors Compliant • Eric O. Recto – Chairman of the Board & Director with collective working Mr. Recto, Filipino, 54 years old, was elected Director and Vice Chairman of the knowledge, experience or Board on July 26, 2011, appointed Co-Chairman of the Board on January 18, 2012 expertise that is relevant to the and Chairman of the Board on May 23, 2012. He is the Chairman and CEO of ISM company’s industry/sector. -

Masterlist of Private Schools Sy 2011-2012

Legend: P - Preschool E - Elementary S - Secondary MASTERLIST OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 MANILA A D D R E S S LEVEL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL HEAD POSITION TELEPHONE NO. No. / Street Barangay Municipality / City PES 1 4th Watch Maranatha Christian Academy 1700 Ibarra St., cor. Makiling St., Sampaloc 492 Manila Dr. Leticia S. Ferriol Directress 732-40-98 PES 2 Adamson University 900 San Marcelino St., Ermita 660 Manila Dr. Luvimi L. Casihan, Ph.D Principal 524-20-11 loc. 108 ES 3 Aguinaldo International School 1113-1117 San Marcelino St., cor. Gonzales St., Ermita Manila Dr. Jose Paulo A. Campus Administrator 521-27-10 loc 5414 PE 4 Aim Christian Learning Center 507 F.T. Dalupan St., Sampaloc Manila Mr. Frederick M. Dechavez Administrator 736-73-29 P 5 Angels Are We Learning Center 499 Altura St., Sta. Mesa Manila Ms. Eva Aquino Dizon Directress 715-87-38 / 780-34-08 P 6 Angels Home Learning Center 2790 Juan Luna St., Gagalangin, Tondo Manila Ms. Judith M. Gonzales Administrator 255-29-30 / 256-23-10 PE 7 Angels of Hope Academy, Inc. (Angels of Hope School of Knowledge) 2339 E. Rodriguez cor. Nava Sts, Balut, Tondo Manila Mr. Jose Pablo Principal PES 8 Arellano University (Juan Sumulong campus) 2600 Legarda St., Sampaloc 410 Manila Mrs. Victoria D. Triviño Principal 734-73-71 loc. 216 PE 9 Asuncion Learning Center 1018 Asuncion St., Tondo 1 Manila Mr. Herminio C. Sy Administrator 247-28-59 PE 10 Bethel Lutheran School 2308 Almeda St., Tondo 224 Manila Ms. Thelma I. Quilala Principal 254-14-86 / 255-92-62 P 11 Blaze Montessori 2310 Crisolita Street, San Andres Manila Ms. -

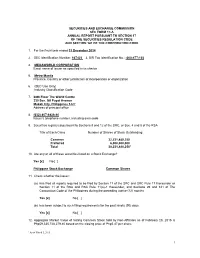

1 Securities and Exchange Commission Sec Form 17-A

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE 1. For the fiscal year ended 31 December 2014 2. SEC Identification Number: 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No.: -000-477-103 4. MEGAWORLD CORPORATION Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter 5. Metro Manila Province, Country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization 6. (SEC Use Only) Industry Classification Code 7. 28th Floor The World Centre 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue Makati City, Philippines 1227 Address of principal office 8. (632) 867-8826-40 Issuer’s telephone number, including area code 9. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC, or Sec. 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Stock Outstanding Common 32,231,480,250 Preferred 6,000,000,000 Total 38,231,480,2501 10. Are any or all of these securities listed on a Stock Exchange? Yes [x] No [ ] Philippine Stock Exchange Common Shares 11. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months. Yes [x] No [ ] (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days. Yes [x] No [ ] 12. Aggregate Market Value of Voting Common Stock held by Non-Affiliates as of February 28, 2015 is Php59,335,728,279.40 based on the closing price of Php5.47 per share. -

Philippine Bank of Communications (PBCOM) Reported a Consolidated Net Income of Php1.17B in 2020

BANKING TABLE OF CONTENTS IN THE NEW About the Cover 1 NORMAL PBCOM Through the Years 2 Our Vision, Mission and Values 3 Chairman’s Message 4 The President Speaks 6 ABOUT THE COVER Banking in the New Normal 10 With a health crisis threatening the world, 2020 was a Our Board of Directors 15 year of challenges for many. A lot of changes had to be Our Senior Management Team 24 made in order to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. For financial institutions such as PBCOM, the challenge is to Our Business 32 continuously provide the necessary financial services to Our Branch and ATM Network 35 the public without compromising the health and safety of both our employees and the banking public. Sustainability Report 43 Corporate Governance 60 This annual report highlights the successes that PBCOM achieved in 2020 in meeting these challenges. Risk and Capital Management 75 Investments in digital capabilities, product Consumer Protection and Experience 93 enhancements, improvements in service delivery, and the implementation of operational changes, are only Financial Highlights 98 some of the major steps we undertook in order to deliver a superior banking experience in the new normal. 1 Our bank, PBCOM, has a very rich history marked by a legacy of strong relationships nurtured through trust and service. And our thrust to focus on you, our clients, is always the center of everything we do. In 2020, we continue our journey towards building a “digital-first” banking experience for our clients. We have formally launched PBCOMobile, the Bank’s all-mobile banking platform to enhance our other digital offerings. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 99 3rd International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE-17) The Strategies of the Popularization of Mandarin Chinese in the Philippines under the New Sino- Philippine Relations Lili Xu Dehui Li The Southern Base of Confucius Institute Headquarters, College of Foreign language and Cultures, Xiamen University Xiamen University Xiamen, China Xiamen, China [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—At present, the popularization of Mandarin there are 167 Philippine Chinese schools(PCS), most of which Chinese (PMC) in the Philippines are facing some problems, such have established courses from kindergarten to middle school. as low effectiveness of class teaching, the obstruction from the mainstream society, fierce competition with other foreign Since the 1990s, conforming to the trend of times, PCS and languages. This article tries to provide some specific suggestions CLE institutes have been exploring new methods on internal on the teaching subjects, contents, channels, and layout mechanism, teaching methodology and international exchanges, considering the analysis of the history and status quo of PMC in which brought in more students coming for schooling. this area. “Students of Chinese descendants are not the only group in schools, the ratio of non-Chinese is still in the rise.”2 On 10th Keywords—Philippines; popularization of Mandarin Chinese; April 2016, the 2nd Summit Conference for the Philippine Sino-Philippine relations; diversification Chinese School hosted by the Tan Yankui Fund and the Center for Chinese Language Education in the Philippines was held in I. INTRODUCTION Manila. Representatives of 96 Chinese schools have come to a The Philippines is located in southeastern Asia and is an new resolution----Carrying Forward CLE Spirit and composing important neighbor of China. -

Exploring the Development Trend of Chinese Education in the Tertiary Level (Philippines)

EXPLORING THE DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION IN THE TERTIARY LEVEL (PHILIPPINES) PROF. DAISY CHENG SEE ABSTRACT This paper traces the changes and developments in Chinese education in the Philippines by a survey of the history thereof. It discusses how Chinese education developed from an education catered to a small number of overseas Chinese to the ethnic Chinese, from an education of students of Chinese descent to mainstream Philippine society in the tertiary level, and the role played by the socio-political environment in this regard. This paper also seeks to answer the question of whether the policy of the Philippine government has anything to do with this development. Difficulties and obstacles to this type of education are discussed. Through an evaluation of the foregoing, this paper proposes some solutions to the perceived problems. This paper uses the investigative exploratory method of study. Books and relevant publications are utilized where necessary. Materials from the Internet from recognized institutions are also used as reference. Interviews and surveys were also conducted in the process of this study. Keywords: Mandarin Linguistic routines; Digital storytelling, Communicative Approach CHINESE STUDIES PROGRAM LECTURE SERIES © Ateneo de Manila University No. 3, 2016: 56–103 http://journals.ateneo.edu SEE / DEVELOPMENT TREND OF CHINESE EDUCATION 57 hinese education in the Philippines refers to the education C taught to ethnic Chinese who became Filipino citizens in Chinese schools after Filipinization.1 Chinese schools have already systematically turned into private Filipino schools that taught the Chinese language (Constitution of the Philippines, 1973).2 Basically, this so-called “Chinese-Filipino education” must have begun in 1976, when Chinese schools in the Philippines underwent comprehensive Filipinization. -

Megaworld Corporation 3

CR04055-2017 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM ACGR ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 1. Report is Filed for the Year Dec 31, 2016 2. Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 3. Address of principal office 28th Floor, The World Centre, 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Makati City Postal Code 1227 4.SEC Identification Number 167423 5. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 6. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 7. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 867-8826 to 40 8. Former name or former address, if changed from the last report N/A The Exchange does not warrant and holds no responsibility for the veracity of the facts and representations contained in all corporate disclosures, including financial reports. All data contained herein are prepared and submitted by the disclosing party to the Exchange, and are disseminated solely for purposes of information. Any questions on the data contained herein should be addressed directly to the Corporate Information Officer of the disclosing party. Megaworld Corporation MEG PSE Disclosure Form ACGR-1 - Annual Corporate Governance Report Reference: Revised Code of Corporate Governance of the Securities and Exchange Commission Description of the Disclosure In compliance with SEC Memorandum Circular No. 20 series of 2016, attached herewith is the Annual Corporate Governance Report (SEC Form-ACGR) of Megaworld Corporation for the year 2016. Filed on behalf by: Name Dohrie Edangalino Designation Head-Corporate Compliance Group MEGAWORLD CORPORATION ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT (SEC FORM – ACGR) FOR YEAR 2016 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM – ACGR ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT 1. -

Downloadable Annual Report Yes

CR02058-2016 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A, AS AMENDED ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF THE CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. For the fiscal year ended Dec 31, 2015 2. SEC Identification Number 167423 3. BIR Tax Identification No. 000-477-103 4. Exact name of issuer as specified in its charter MEGAWORLD CORPORATION 5. Province, country or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization Metro Manila 6. Industry Classification Code(SEC Use Only) 7. Address of principal office 28th Floor, The World Centre, 330 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Makati City Postal Code 1227 8. Issuer's telephone number, including area code (632) 8678826 to 40 9. Former name or former address, and former fiscal year, if changed since last report N/A 10. Securities registered pursuant to Sections 8 and 12 of the SRC or Sections 4 and 8 of the RSA Title of Each Class Number of Shares of Common Stock Outstanding and Amount of Debt Outstanding Common 32,239,445,872 Preferred 6,000,000,000 11. Are any or all of registrant's securities listed on a Stock Exchange? Yes No If yes, state the name of such stock exchange and the classes of securities listed therein: Philippine Stock Exchange, Common Shares 12. Check whether the issuer: (a) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 17 of the SRC and SRC Rule 17.1 thereunder or Section 11 of the RSA and RSA Rule 11(a)-1 thereunder, and Sections 26 and 141 of The Corporation Code of the Philippines during the preceding twelve (12) months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports) Yes No (b) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past ninety (90) days Yes No 13. -

Chemistry According to Kids

Chemistry According to KKidsids by Lida Schoen n order to celebrate 2006 as the Year of Chemistry in Korea, the Korean Chemical Society (KCS) initiated and sponsored a Iglobal poster competition. Choon Do of the KCS collaborated with IUPAC’s Committee on Chemistry Education (CCE) and Lida Schoen of the Science Across the World program to launch the poster competition, which culminated with a display during the International Conference on Chemical Education (ICCE) held in Seoul in August 2006. Lida Schoen administered and managed the competition with the support of the SAW network. Chemistry for Humanity The theme for this poster competition was that of the Rosalyn T. Yu (age 14), Philippines conference: “Chemistry for Humanity.” Therefore, stu- dents who entered the contest were asked to visualize their ideas on this general concept. The contest offered two age categories: 10–13 and 14–16. Altogether, 944 entries were received from 32 different countries: 427 on paper and 517 electronic files in various formats. From these entries, 13 posters from the age 10-13 category and 41 posters from the age 14–16 category were preselected. There were no separate categories for paper and electronic entries. Criteria for the jury were as follows: y relevance to the theme Maria Prasilova (age 16), Slovak Republic y clear message, communi- cation value y artistic value: color, composition y universally understandable, with little or no text An exhibition of these posters was on display at the 19th International Conference on Chemical Education (ICCE) from 12–17 August 2006 in Seoul, Korea. Around 300 chemists from all over the world were able to admire the selections (for more about the ICCE, see conference report on p. -

PRIVATE EDUCATION ASSISTANCE COMMITTEE NATIONAL SECRETARIAT 25Th Floor Philippine AXA Life Centre 1286 Sen

PRIVATE EDUCATION ASSISTANCE COMMITTEE NATIONAL SECRETARIAT 25th Floor Philippine AXA Life Centre 1286 Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue corner Tindalo St., Makati City SCHEDULE OF SCHOOLS TO UNDERGO eCERTIFICATION of APPLICANT SCHOOLS SY 2020 – 2021 (March 1, 2021 – March 26, 2021) To facilitate the eCertification process, kindly prepare the following: 1. Ensure that the initial documentary requirements (Part I and II) have been uploaded in the EIS (https://eis.peac.org.ph/) 2. Make certain that the required ECEs (Part III) have also been submitted online (via Google Drive or OneDrive) or courier thru PEAC NS (please refer to https://peac.org.ph/certification/) 3. Duration of eCertification is whole day (7:00AM-4:00PM) via Zoom App (email will be sent to the schools concerned indicating the details pertinent to eRecertification) 4. Check the equipment/devices to be used are working; and that there is a stable internet connection. 5. All key personnel, JHS teachers and selected ESC students (JHS) must make themselves available for the interviews if the need arises. 6. **Results will be released once all scheduled Certification activities are done. 7. **Schedule for other Certification activities for SY2020-2021 will be posted separately. For inquiries, concerns and clarifications on eCertification: Certification Unit Email Address: [email protected] Mobile: 0917-5013669/0917-3070071 1 REGION NCR METRO MANILA March 1, 2021 1404147 The Lord's Wisdom Academy of Caloocan Inc., Caloocan, Metro Manila March 2, 2021 1404148 Jean-Captiste of Reims -

Download Must Have Seized Their Attention

Communicating climate change in the rice sector JAIME A. MANALO IV with ANNA MARIE F. BAUTISTA JAYSON C. BERTO ROMMEL T. HALLARES FREDIERICK M. SALUDEZ JENNIFER VILLAFLOR-MESA November 2017 Communicating climate change in the rice sector 3 Disclaimer: All positions and views expressed in this book are sole responsibilities of the authors who do not claim to represent the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice), Department of Education (DepEd), or CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CGIAR-CCAFS). Copyright 2017 © DA-Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice) and DA-Bureau of Agricultural Research (BAR). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced; stored in a retrieval system; or transmitted in any way or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without written permission of the copyright holders. Published by: DA-Philippine Rice Research Institute Maligaya, Science City of Muñoz, 3119 Nueva Ecija Website: www.philrice.gov.ph Email: [email protected] Tel: (044) 456-0258; -0285 DA-Bureau of Agricultural Research Diliman, Quezon City Website: www.bar.gov.ph Tel: (02) 928-8505 Graphic design and layout by Jayson C. Berto Language edited by Constante T. Briones ISBN NO. 978-621-8022-33-1 Printed in the Philippines Note: We asked parents and/or guardians of students to allow us to use their photos in this publication. Table of contents Title page i Table of contents iii Foreword iv Acknowledgment vi Lists of figures and tables viii Introduction -

ENROLMENT in PRIVATE PRE-SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 As of September 30, 2011

ENROLMENT IN PRIVATE PRE-SCHOOLS SY 2011-2012 As of September 30, 2011 Division / School Male Female Total NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION 42,775 41,530 84,305 001 City of Manila 4,759 4,873 9,632 002 Quezon City 10,911 10,627 21,538 003 Pasay City 1,064 1,045 2,109 004 Caloocan City 2,269 2,335 4,604 005 City of Mandaluyong 1,422 926 2,348 006 Marikina City 2,266 2,281 4,547 007 Makati City 2,607 2,647 5,254 008 Pasig City 3,503 3,664 7,167 Interim San Juan City 1,344 1,171 2,515 009 Parañaque City 2,263 2,175 4,438 010 City of Las Piñas 2,427 2,360 4,787 011 Valenzuela City 1,738 1,820 3,558 012 City of Malabon 1,063 972 2,035 Navotas City 389 323 712 013 Taguig City/Pateros 2,608 2,392 5,000 014 City of Muntinlupa 2,142 1,919 4,061 Private Preschool Enrolment / SY 2011-2012 Page 1 of 55 Division / School Male Female Total NATIONAL001 CITY CAPITAL OF MANILA REGION 4,759 4,873 9,632 1 Adamson University 23 27 50 2 Aguinaldo International School (Emilio Aguinaldo College Science High School) 24 8 32 3 Aim Christian Learning Center 22 14 36 4 Arellano University (J. Sumulong HS) 24 23 47 5 Asuncion Learning Center 14 16 30 6 Bethel Lutheran School 7 8 15 7 Blaze Montessori 62 70 132 8 Build Up Knowledge Learning Center 73 50 123 9 Central Methodist Educational Center 14 8 22 10 Chiang Kai Shek College 388 326 714 11 Christian Academy of Manila 3 8 11 12 Colegio de San Juan de Letran 34 13 47 13 Colegio de Sta.