B39578e9fcaf9c5935ea0651609

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Aspergillus Flavus Soil and Corn Kernel Populations from Eight Mississippi River States Jorge A

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 11-13-2017 Characterization of Aspergillus Flavus Soil and Corn Kernel Populations From Eight Mississippi River States Jorge A. Reyes Pineda Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Agricultural Science Commons, Agriculture Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Reyes Pineda, Jorge A., "Characterization of Aspergillus Flavus Soil and Corn Kernel Populations From Eight Mississippi River States" (2017). LSU Master's Theses. 4350. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4350 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERIZATION OF ASPERGILLUS FLAVUS SOIL AND CORN KERNEL POPULATIONS FROM EIGHT MISSISSIPPI RIVER STATES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Plant Pathology and Crop Physiology by Jorge A. Reyes Pineda B.S., Universidad Nacional de Agricultura-Honduras 2011 December 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first thank God who gave me the strength and perseverance to complete the requirements for this degree, and second, I thank my family. Without their unconditional support and encouragement, I would have never been able to achieve this endeavor. I would like to thank my advisory committee, Drs. -

Review of Oxepine-Pyrimidinone-Ketopiperazine Type Nonribosomal Peptides

H OH metabolites OH Review Review of Oxepine-Pyrimidinone-Ketopiperazine Type Nonribosomal Peptides Yaojie Guo , Jens C. Frisvad and Thomas O. Larsen * Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, Søltofts Plads, Building 221, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark; [email protected] (Y.G.); [email protected] (J.C.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +45-4525-2632 Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 15 June 2020 Abstract: Recently, a rare class of nonribosomal peptides (NRPs) bearing a unique Oxepine-Pyrimidinone-Ketopiperazine (OPK) scaffold has been exclusively isolated from fungal sources. Based on the number of rings and conjugation systems on the backbone, it can be further categorized into three types A, B, and C. These compounds have been applied to various bioassays, and some have exhibited promising bioactivities like antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi and transcriptional activation on liver X receptor α. This review summarizes all the research related to natural OPK NRPs, including their biological sources, chemical structures, bioassays, as well as proposed biosynthetic mechanisms from 1988 to March 2020. The taxonomy of the fungal sources and chirality-related issues of these products are also discussed. Keywords: oxepine; nonribosomal peptides; bioactivity; biosynthesis; fungi; Aspergillus 1. Introduction Nonribosomal peptides (NRPs), mostly found in bacteria and fungi, are a class of peptidyl secondary metabolites biosynthesized by large modularly organized multienzyme complexes named nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) [1]. These products are amongst the most structurally diverse secondary metabolites in nature; they exhibit a broad range of activities, which have been exploited in treatments such as the immunosuppressant cyclosporine A and the antibiotic daptomycin [2,3]. -

Monograph on Dematiaceous Fungi

Monograph On Dematiaceous fungi A guide for description of dematiaceous fungi fungi of medical importance, diseases caused by them, diagnosis and treatment By Mohamed Refai and Heidy Abo El-Yazid Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University 2014 1 Preface The first time I saw cultures of dematiaceous fungi was in the laboratory of Prof. Seeliger in Bonn, 1962, when I attended a practical course on moulds for one week. Then I handled myself several cultures of black fungi, as contaminants in Mycology Laboratory of Prof. Rieth, 1963-1964, in Hamburg. When I visited Prof. DE Varies in Baarn, 1963. I was fascinated by the tremendous number of moulds in the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, Netherlands. On the other hand, I was proud, that El-Sheikh Mahgoub, a Colleague from Sundan, wrote an internationally well-known book on mycetoma. I have never seen cases of dematiaceous fungal infections in Egypt, therefore, I was very happy, when I saw the collection of mycetoma cases reported in Egypt by the eminent Egyptian Mycologist, Prof. Dr Mohamed Taha, Zagazig University. To all these prominent mycologists I dedicate this monograph. Prof. Dr. Mohamed Refai, 1.5.2014 Heinz Seeliger Heinz Rieth Gerard de Vries, El-Sheikh Mahgoub Mohamed Taha 2 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. 30. The genus Rhinocladiella 83 2. Description of dematiaceous 6 2. 31. The genus Scedosporium 86 fungi 2. 1. The genus Alternaria 6 2. 32. The genus Scytalidium 89 2.2. The genus Aurobasidium 11 2.33. The genus Stachybotrys 91 2.3. The genus Bipolaris 16 2. -

Clinical and Laboratory Profile of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Original article 109 Clinical and laboratory profile of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: a retrospective study Ramakrishna Pai Jakribettua, Thomas Georgeb, Soniya Abrahamb, Farhan Fazalc, Shreevidya Kinilad, Manjeshwar Shrinath Baligab Introduction Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is a type differential leukocyte count, and erythrocyte sedimentation of semi-invasive aspergillosis seen mainly in rate. In all the four dead patients, the cause of death was immunocompetent individuals. These are slow, progressive, respiratory failure and all patients were previously treated for and not involved in angio-invasion compared with invasive pulmonary tuberculosis. pulmonary aspergillosis. The predisposing factors being Conclusion When a patient with pre-existing lung disease compromised lung parenchyma owing to chronic obstructive like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or old tuberculosis pulmonary disease and previous pulmonary tuberculosis. As cavity presents with cough with expectoration, not many studies have been conducted in CPA with respect to breathlessness, and hemoptysis, CPA should be considered clinical and laboratory profile, the study was undertaken to as the first differential diagnosis. examine the profile in our population. Egypt J Bronchol 2019 13:109–113 Patients and methods This was a retrospective study. All © 2019 Egyptian Journal of Bronchology patients older than 18 years, who had evidence of pulmonary Egyptian Journal of Bronchology 2019 13:109–113 fungal infection on chest radiography or computed tomographic scan, from whom the Aspergillus sp. was Keywords: chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, immunocompetent, laboratory isolated from respiratory sample (broncho-alveolar wash, parameters bronchoscopic sample, etc.) and diagnosed with CPA from aDepartment of Microbiology, Father Muller Medical College Hospital, 2008 to 2016, were included in the study. -

Emerging Health Concerns in the Era of Cannabis Legalization

Emerging Health Concerns in the Era of Cannabis Legalization Iyad N. Daher, MD, FACC, FASE, FSCCT Chief Science Officer, VRX Labs Cannabis legalization is advancing worldwide * complicated … * Legalization impact on population use and health hazards More first-time users More volume of consumption (more exposure) More matrices (smoke/vape/cookies/gummies/drinks) More access to vulnerable populations (young, elderly, cancer, immunocompromised, fertile females, pregnant) More potential for inappropriate/accidental use (young, driving, operating machinery) More apparent cannabis related medical problems (increased reporting) Cannabis population health impact is yet to be fully understood Limited US federal funding Restrictions on research even with private funds (stigma, loss of federal funding) Paucity of quality data (small numbers, case reports, no longitudinal studies, biases (reporting/publishing/authors/editors/reviewers) Post marketing studies NOT mandated at this time How do these concerns compare with alcohol? Alcohol like Cannabis specific first time users Increased cannabis related medical problems (psychiatric, Increased exposure bad experience, vulnerable populations contaminants) (young, pregnant) More matrices inappropriate/accidental use (smoke/vape/cookies/gummie (young, driving, operating s/drinks) machinery) vulnerable populations (elderly, More apparent cancer, immunocompromised, fertile or pregnant females): contaminants Comparison to alcohol is useful but has limitations Cannabis and derived THC/CBD have -

Characterization of Terrelysin, a Potential Biomarker for Aspergillus Terreus

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus Ajay Padmaj Nayak West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Nayak, Ajay Padmaj, "Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 3598. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/3598 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Characterization of terrelysin, a potential biomarker for Aspergillus terreus Ajay Padmaj Nayak Dissertation submitted to the School of Medicine at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Immunology and Microbial Pathogenesis Donald H. Beezhold, -

Safety of the Fungal Workhorses of Industrial Biotechnology: Update on the Mycotoxin and Secondary Metabolite Potential of Asper

View metadata,Downloaded citation and from similar orbit.dtu.dk papers on:at core.ac.uk Mar 29, 2019 brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research Database In Technology Safety of the fungal workhorses of industrial biotechnology: update on the mycotoxin and secondary metabolite potential of Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, and Trichoderma reesei Frisvad, Jens Christian; Møller, Lars L. H.; Larsen, Thomas Ostenfeld; Kumar, Ravi; Arnau, Jose Published in: Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology Link to article, DOI: 10.1007/s00253-018-9354-1 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Frisvad, J. C., Møller, L. L. H., Larsen, T. O., Kumar, R., & Arnau, J. (2018). Safety of the fungal workhorses of industrial biotechnology: update on the mycotoxin and secondary metabolite potential of Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus oryzae, and Trichoderma reesei. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 102(22), 9481-9515. DOI: 10.1007/s00253-018-9354-1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Interaction Between Tribolium Castaneum and Mycotoxigenic Aspergillus flavus in Maize Flour

insects Article The Interaction between Tribolium castaneum and Mycotoxigenic Aspergillus flavus in Maize Flour Sónia Duarte 1,2 , Ana Magro 1,*, Joanna Tomás 1, Carolina Hilário 1, Paula Alvito 3,4, Ricardo Boavida Ferreira 1,2 and Maria Otília Carvalho 1,2 1 Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] (S.D.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (R.B.F.); [email protected] (M.O.C.) 2 LEAF—Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal 3 National Health Institute Dr. Ricardo Jorge (INSA), 1600-609 Lisboa, Portugal; [email protected] 4 Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM), University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: It is important to hold cereals in storage conditions that exclude insect pests such as the red flour beetle and fungi, especially mycotoxin-producing ones (as a few strains of Aspergillus flavus). This work aims to investigate the interaction between these two organisms when thriving in maize flour. It was observed that when both organisms were together, the mycotoxins detected in maize flour were far higher than when the fungi were on their own, suggesting that the presence of insects may contribute positively to fungi development and mycotoxin production. The insects in Citation: Duarte, S.; Magro, A.; contact with the fungi were almost all dead at the end of the trials, suggesting a negative effect of the Tomás, J.; Hilário, C.; Alvito, P.; fungi growth on the insects. -

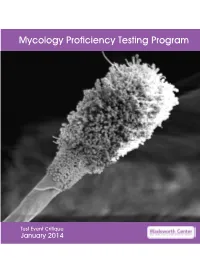

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program

Mycology Proficiency Testing Program Test Event Critique January 2014 Table of Contents Mycology Laboratory 2 Mycology Proficiency Testing Program 3 Test Specimens & Grading Policy 5 Test Analyte Master Lists 7 Performance Summary 11 Commercial Device Usage Statistics 13 Mold Descriptions 14 M-1 Stachybotrys chartarum 14 M-2 Aspergillus clavatus 18 M-3 Microsporum gypseum 22 M-4 Scopulariopsis species 26 M-5 Sporothrix schenckii species complex 30 Yeast Descriptions 34 Y-1 Cryptococcus uniguttulatus 34 Y-2 Saccharomyces cerevisiae 37 Y-3 Candida dubliniensis 40 Y-4 Candida lipolytica 43 Y-5 Cryptococcus laurentii 46 Direct Detection - Cryptococcal Antigen 49 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Yeast 52 Antifungal Susceptibility Testing - Mold (Educational) 54 1 Mycology Laboratory Mycology Laboratory at the Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) is a reference diagnostic laboratory for the fungal diseases. The laboratory services include testing for the dimorphic pathogenic fungi, unusual molds and yeasts pathogens, antifungal susceptibility testing including tests with research protocols, molecular tests including rapid identification and strain typing, outbreak and pseudo-outbreak investigations, laboratory contamination and accident investigations and related environmental surveys. The Fungal Culture Collection of the Mycology Laboratory is an important resource for high quality cultures used in the proficiency-testing program and for the in-house development and standardization of new diagnostic tests. Mycology Proficiency Testing Program provides technical expertise to NYSDOH Clinical Laboratory Evaluation Program (CLEP). The program is responsible for conducting the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-compliant Proficiency Testing (Mycology) for clinical laboratories in New York State. All analytes for these test events are prepared and standardized internally. -

Enzymatic Potential of Bacteria and Fungi Isolates from the Sewage Sludge Composting Process

applied sciences Article Enzymatic Potential of Bacteria and Fungi Isolates from the Sewage Sludge Composting Process 1,2, 1,2 1,2, Tatiana Robledo-Mahón y , Concepción Calvo and Elisabet Aranda * 1 Institute of Water Research, University of Granada, Ramón y Cajal 4, 18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] (T.R.-M.); [email protected] (C.C.) 2 Department of Microbiology, Pharmacy Faculty, University of Granada, Campus de Cartuja s/n, 18071 Granada, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Current address: Department of Agro-Environmental Chemistry and Plant Nutrition, y Faculty of Agrobiology, Food and Natural Resources, Czech University of Life Sciences, Kamýcká 129, 16500 Prague 6-Suchdol, Czech Republic. Received: 6 October 2020; Accepted: 2 November 2020; Published: 3 November 2020 Featured Application: Screening of suitable microorganisms adapted to environmental conditions are the challenges for the optimization of biotechnological processes in the current and near future. Some of the isolated microorganisms in this study possess biotechnological desirable features which could be employed in different processes, such as biorefinery, bioremediation, or in the food industry. Abstract: The aim of this study was the isolation and characterisation of the fungi and bacteria during the composting process of sewage sludge under a semipermeable membrane system at full scale, in order to find isolates with enzymatic activities of biotechnological interest. A total of 40 fungi were isolated and enzymatically analysed. Fungal culture showed a predominance of members of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota division and some representatives of Mucoromycotina subdivision. Some noticeable fungi isolated during the mesophilic and thermophilic phase were Aspergillus, Circinella, and Talaromyces. -

New Species in Aspergillus Section Terrei

available online at www.studiesinmycology.org StudieS in Mycology 69: 39–55. 2011. doi:10.3114/sim.2011.69.04 New species in Aspergillus section Terrei R.A. Samson1*, S.W. Peterson2, J.C. Frisvad3 and J. Varga1,4 1CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Uppsalalaan 8, NL-3584 CT Utrecht, the Netherlands; 2Microbial Genomics and Bioprocessing Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, 1815 N. University Street, Peoria, IL 61604, USA; 3Department of Systems Biology, Building 221, Technical University of Denmark, DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark; 4Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science and Informatics, University of Szeged, H-6726 Szeged, Közép fasor 52, Hungary. *Correspondence: Robert A. Samson, [email protected] Abstract: Section Terrei of Aspergillus was studied using a polyphasic approach including sequence analysis of parts of the β-tubulin and calmodulin genes and the ITS region, macro- and micromorphological analyses and examination of extrolite profiles to describe three new species in this section. Based on phylogenetic analysis of calmodulin and β-tubulin sequences seven lineages were observed among isolates that have previously been treated as A. terreus and its subspecies by Raper & Fennell (1965) and others. Aspergillus alabamensis, A. terreus var. floccosus, A. terreus var. africanus, A. terreus var. aureus, A. hortai and A. terreus NRRL 4017 all represent distinct lineages from the A. terreus clade. Among them, A. terreus var. floccosus, A. terreus NRRL 4017 and A. terreus var. aureus could also be distinguished from A. terreus by using ITS sequence data. New names are proposed for A. terreus var. floccosus, A. terreus var. -

Molecular Microbial Enumeration Tests and the Limitation of Colony Forming Units

Microbiological examination of nonsterile Cannabis products: Molecular Microbial Enumeration Tests and the limitation of Colony Forming Units. Kevin McKernan, Yvonne Helbert, Heather Ebling, Adam Cox, Liam T. Kane, Lei Zhang Medicinal Genomics, Woburn MA Cannabis microbial testing presents unique challenges. Unlike food testing, cannabis testing has to consider various routes oF administration beyond just oral administration. Cannabis flowers produce high concentrations oF antimicrobial cannabinoids and terpenoids and thus represent a diFFerent matrix than traditional Foods 1, 2. In 2018, it is estimated that 50% oF cannabis is consumed via vaporizing or smoking oils and Flowers while the other halF is consumed in Marijuana InFused Products or MIPs. There are also transdermal patches, salves and suppositories that all present diFFerent microbial considerations. Several recent publications have surveyed cannabis Flower microbiological communities3-5. These have detected several concerning genus and species such as Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, Penicillium paxilli and Penicillium citrinum, Clostridium botulinum, Eschericia coli, Salmonella and Staphyloccus. There are several documented cannabis complications and even Fatalities due to Aspergillosis in immuno-compromised patients6-18. A recent paper even demonstrates a case oF cannabis derived Aspergillosis in an immune competent patient19. It is unknown to what extent Aspergillus produces mycotoxins in cannabis and to what extent those toxins enrich in the cannabis extraction process. Llewellyn et al . published laboratory settings where to 8.7ug/g oF aflatoxin could be produce with inoculated “marihuana” but the work was perFormed in 1977 and still leaves many questions regarding iF this can occur in the wild 20. It is also unknown if Clostridium botulinum produces botulinum toxin in cannabis oils.