</I> Gender Naming in the Marketing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pitzer Senior Theses Pitzer Student Scholarship 2014 Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960 Dahnya Nicole Hernandez Pitzer College Recommended Citation Hernandez, Dahnya Nicole, "Funny Pages: Comic Strips and the American Family, 1930-1960" (2014). Pitzer Senior Theses. Paper 60. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pitzer_theses/60 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pitzer Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pitzer Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FUNNY PAGES COMIC STRIPS AND THE AMERICAN FAMILY, 1930-1960 BY DAHNYA HERNANDEZ-ROACH SUBMITTED TO PITZER COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE FIRST READER: PROFESSOR BILL ANTHES SECOND READER: PROFESSOR MATTHEW DELMONT APRIL 25, 2014 0 Table of Contents Acknowledgements...........................................................................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................3 Chapter One: Blondie.....................................................................................................................................18 Chapter Two: Little Orphan Annie............................................................................................................35 -

In Texas * That Going to College Is Un (ELL)

IN T E CH OIL,A STIC VOL. XVI AUSTIN, TEXAS, JANUARY, 1933 No. 5 150 Counties Report Kenley Says Four Years LETTEK County Enough in High School Corsicana Wins Conference A SPANISH CONTEST IN BOX and League Organizations to Date JEFFERSON COUNTY PERSONAL PRINCIPAL CHESTER H. KEJST- Football Over Masonic Home ITEMS -*- LEY, of San Antonio High Instructor Says Greatest Diffi Counties Not Included in List Urged to Report Now School, writes the LEAGUES, as Eight Conference B Regional Winners Declared culty Is in Securing Prop follows: er Tests for Pupils. >OUNTIES that have not RDERING plays for trial from re Good-Night Good-Will On "I was unable to attend the Writer Endorses 8-Semester Thirteenth Annual Foot- O the Loan Library service, Mrs. ported officers should do so Gridiron Writer Implies ball State Championship sea T AST spring I was director Kahat Baker, of Carthage, gives some League breakfast at Ft. Worth, And One-Year Transfer Rule at once, if election has already so I have just read with interest son under the auspices of the ^-* for Spanish in Jefferson account of herself since she was a ;aken place. In many counties AIUS SHAVER in Colliers County and wrote you for sug participant in Interscholastic League ;he account of the discussion on TF the high schools of the state University Interscholastic nstitutes have not yet been held (Nov. 18) says Bob Hall, gestions for conducting the herself: :he transfer and the 8 semester will stick by the one-year League closed with the game be Last year our and in some other counties in former Masonic Home (Fort affair. -

The Landon School of Illustrating and Cartooning

The Landon School of Illustrating and Cartooning by Charles N. Landon 1922 Facsimile Edition edited by John Garvin Copyright 2009 by John Garvin www.johngarvin.com Published by Enchanted Images Inc. www.enchantedimages.com All illustrations in this book are copyrighted by their respective copy- right holders (according to the original copyright or publication date as printed in/on the original work) and are reproduced for historical reference and research purposes. Any omission or incorrect informa- tion should be transmitted to the publisher, so it can be rectified in future editions of this book. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other- wise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9785946-3-3 Second Edition First Printing November 2009 Edition size: 250 Printed in the United States of America 2 Preface (First Edition) This book began as part of a research project on Carl Barks. In various inter- views Barks had referred to the “Landon correspondence course in cartooning” he’d taken when he was sixteen. Fascinated, I tried to find a copy of Landon’s course. After a couple of years of searching on eBay and other auction houses – where I was only able to find partial copies – I finally tracked down a com- plete copy from a New York rare book dealer. In the meantime, my research revealed that more than a few cartoonists from Barks’s generation had taken the Landon course. -

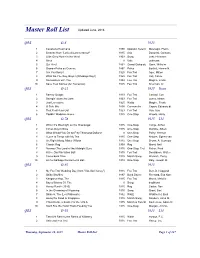

Master Roll List

Master Roll List QRS O-6 1925 1 Cavalleria Rusticana 1890 Operatic Selecti Mascagni, Pietro 2 Sextette from "Lucia di Lammermoor" 1835 Aria Donizetti, Gaetano 3 Little Grey Home in the West 1903 Song Lohr, Hermann 4 Alma 0 Vals unknown 5 Qui Vive! 1862 Grand Galop de Ganz, Wilhelm 6 Grande Polka de Concert 1867 Polka Bartlett, Homer N. 7 Are You Sorry? 1925 Fox Trot Ager, Milton 8 What Do You Say, Boys? (Whadaya Say?) 1925 Fox Trot Voll, Cal de 9 Somewhere with You 1924 Fox Trot Magine, Frank 10 Save Your Sorrow (for Tomorrow) 1925 Fox Trot Sherman, Al QRS O-21 1925 Roen 1 Barney Google 1923 Fox Trot Conrad, Con 2 Swingin' down the Lane 1923 Fox Trot Jones, Isham 3 Just Lonesome 1925 Waltz Magine, Frank 4 O Solo Mio 1898 Canzonetta Capua, Eduardo di 5 That Red Head Gal 1923 Fox Trot Van, Gus 6 Paddlin' Madeline Home 1925 One-Step Woods, Harry QRS O-78 1915 Lbl 1 When It's Moonlight on the Mississippi 1915 One-Step Lange, Arthur 2 Circus Day in Dixie 1915 One-Step Gumble, Albert 3 What Would You Do for Fifty Thousand Dollars? 0 One-Step Paley, Herman 4 I Love to Tango with My Tea 1915 One-Step Alstyne, Egbert van 5 Go Right Along, Mister Wilson 1915 One-Step Brown, A. Seymour 6 Classic Rag 1909 Rag Moret, Neil 7 Norway (The Land of the Midnight Sun) 1915 One-Step, Trot Fisher, Fred 8 At the Old Plantation Ball 1915 Fox Trot Donaldson, Walter 9 Come back Dixie 1915 March Song Wenrich, Percy 10 At the Garbage Gentlemen's Ball 1914 One-Step Daly, Joseph M. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

FROM SERIAL DEATH TO PROCEDURAL LOVE: A STUDY OF SERIAL CULTURE By STEPHANIE BOLUK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Stephanie Boluk 2 For my mum 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS One of the reasons I chose to come to the University of Florida was because of the warmth and collegiality I witnessed the first time I visited the campus. I am grateful to have been a member of such supportive English department. A huge debt of gratitude is owed to my brilliant advisor Terry Harpold and rest of my wonderful committee, Donald Ault, Jack Stenner, and Phil Wegner. To all of my committee: a heartfelt thank you. I would also like to thank all the members of Imagetext, Graduate Assistants United, and Digital Assembly (and its predecessor Game Studies) for many years of friendship, fun, and collaboration. To my friends and family, Jean Boluk, Dan Svatek, and the entire LeMieux clan: Patrick, Steve, Jake, Eileen, and Vince, I would not have finished without their infinite love, support, patience (and proofreading). 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 11 Serial Ancestors..................................................................................................... -

Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 2001 Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library Chad Wheaton Syracuse University Carolyn A. Davis Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wheaton, Chad and Davis, Carolyn A., "Cultural History and Comics Auteurs: Cartoon Collections at Syracuse University Library" (2001). The Courier. 337. https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/337 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIB RA RY ASS 0 CI ATE S c o URI E R VOLUME XXXIII . 1998-2001 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VO LU ME XXXIII 1998-2001 Franz Leopold Ranke, the Ranke Library at Syracuse, and the Open Future ofScientific History By Siegfried Baur, Post-Doctoral Fellow 7 Thyssen Foundation ofCologne, Germany Baur pays tribute to "the father ofmodern history," whose twenty-ton library crossed the Atlantic in 1888, arriving safely at Syracuse University. Mter describ ing various myths about Ranke, Baur recounts the historian's struggle to devise, in the face ofaccepted fictions about the past, a source-based approach to the study ofhistory. Librarianship in the Twenty-First Century By Patricia M. Battin, Former Vice President and 43 University Librarian, Columbia University Battin urges academic libraries to "imagine the future from a twenty-first cen tury perspective." To flourish in a digital society, libraries must transform them selves, intentionally and continuously, through managing information resources, redefining roles ofinformation professionals, and nourishing future leaders. -

![The IOWAVE [Newspaper], July 28, 1944](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8868/the-iowave-newspaper-july-28-1944-3848868.webp)

The IOWAVE [Newspaper], July 28, 1944

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks The IOWAVE [newspaper] WAVES on Campus January 1944 The IOWAVE [newspaper], July 28, 1944 United States. Naval Reserve. Women's Reserve. Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1944 IOWAVES Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/iowave_newspaper Part of the Military and Veterans Studies Commons Recommended Citation United States. Naval Reserve. Women's Reserve., "The IOWAVE [newspaper], July 28, 1944" (1944). The IOWAVE [newspaper]. 37. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/iowave_newspaper/37 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the WAVES on Campus at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The IOWAVE [newspaper] by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JO WAVE Dedicated to all IOWAV~S in Training and Afiel.l Volume lll~No. 4 U. S. NAVAL TRAINING SCHOOL, CEDAR FALLS. IOWA 28 JULY 1944 War Highlights WAVES Observe Second Anniversary GERMANY Adolph Hitler, in one of the most 500 Civilian Guests <lra tic decrees he has ever issued, Admiral Taylor Two Staff Members ordered total mobilization of every resource - human and material - Stresses Fine Go To New Duty To Observe Navy occupied throughout Germany and Lt. (jg) Lewise Henderson bids territories, and named Reich Marshal Record of W.R. Station Activities Goering his mobilization the USS BARTLETT "farewell" after Hermann "It is fitting on this occasion, when The second anniversary of the he named Dr. Joseph sixteen months in Cedar Falls. She dictator. Goering the second anniversary of the estab ginning of the \Vomen's Reserve of Goebbels, propoganda minister and reports to BuShips in \Vashington, lishment of the vVomen's Reserve is the United States Navy will be ob his bitterest personal enemy, "pleni soon to be celebrated, to note that D. -

Editor & Publisher International Year Books

Content Survey & Selective Index For Editor & Publisher International Year Books *1929-1949 Compiled by Gary M. Johnson Reference Librarian Newspaper & Current Periodical Room Serial & Government Publications Division Library of Congress 2013 This survey of the contents of the 1929-1949 Editor & Publisher International Year Books consists of two parts: a page-by-page selective transcription of the material in the Year Books and a selective index to the contents (topics, names, and titles) of the Year Books. The purpose of this document is to inform researchers about the contents of the E&P Year Books in order to help them determine if the Year Books will be useful in their work. Secondly, creating this document has helped me, a reference librarian in the Newspaper & Current Periodical Room at the Library of Congress, to learn about the Year Books so that I can provide better service to researchers. The transcript was created by examining the Year Books and recording the items on each page in page number order. Advertisements for individual newspapers and specific companies involved in the mechanical aspects of newspaper operations were not recorded in the transcript of contents or added to the index. The index (beginning on page 33) attempts to provide access to E&P Year Books by topics, names, and titles of columns, comic strips, etc., which appeared on the pages of the Year Books or were mentioned in syndicate and feature service ads. The headings are followed by references to the years and page numbers on which the heading appears. The individual Year Books have detailed indexes to their contents. -

Of Shotguns, Rifles

' T-r i f ™ , V NET PRESS RUN ; fU E WEATHER AVERAGE DAiLV OlRGUIiATION V ' Peveeast hr O* Weather Barean. for the Month of Mny, 1029 I , Be«* Ua«ea 5.330 FB lr: toiUght; Wednesday ln« Memben ot the A edit Bareaa of Ctrcalatlone ■ . ■ V/r '-r>. -creasing cdondlness. , ' Conn. State Library— Comp. VOL. X U IL , NO. 208. (Clawlfled Advertising on Page 10) SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, JUNE 18, 1921 *T»-B»trv ii: PAGES PRICE THREE CENTS UTTLE ORPHAN, CONGRESS SET Principals in Ohio Murder THREEBODIES SEEKING ICE IN FOR VACATION; STILLREMAIN \ R 0A D , IS KILLED VOTKREIEF IN ^A N N E L OF SHOTGUNS, RIFLES Sammy Poleu, Whose Fam Orders Tariff Revision and Four Others R kovered from Dry Killings in Last Few Days Wave irf Protest A g ^ ily Life Has Been Tragic, Appropriates 150 Mil Plane Which Crashed In Start Discussion All Over U. S., Recent Killings Along The seething cauldron of public dissension and-public ap Dies in Hospital After Be lions for Fanners—To to English Channel— One probation over recent dry killings reached a new maximum of Canadian Border Forces intensity today as development followed development. ing Struck by Autoist. Adjourn Tomorrow. Was An American. Within the last 24-hours, International News Service dis Treasury Department to. patches indicated, the following events injected themselves in Little Sammy Poleu. four y^ rs Washington, June 18.— After or . Folkestone, England, June 18— to the situation! .Issue Strict Regulations; old orphan, died at the Memorial dering a general revision of the A grim search continued today for 1. -

Eastern Progress 1932-1933 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1932-1933 Eastern Progress 3-10-1933 Eastern Progress - 10 Mar 1933 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1932-33 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 10 Mar 1933" (1933). Eastern Progress 1932-1933. 11. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1932-33/11 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1932-1933 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' . - .. ' " - 4 •'» THE EASTERN PROGRESS Eaitern Kentucky State teachers College VOLUME XI RICHMOND, KENTUCKY, FRIDAY, MARCH 10, 1933 NUMBER 11 REGIONAL MEET OPENS HERE TODAY \ SCHOOL HEADS BEAUTY QUEEN DR. DONOVAN EASTERN WILL Jaggers Be Here PLAY BEGINS WILL CONVENE, RETURNS FROM HOLD SPRING AT 3 O'CLOCK EASTERN HOST WEEKS TOUR GRID PRACTICE EASTERN GYM Meeting of County Superin- Eastern President Been At- Uniforms Issued This After- Speedwell Plays B. B .1. and tendents Be Held March tending American Associa- noon, Practice to be Held Berea Academy Meets Bar- 23 and 24 tion Teachers Colleges on Days When Weather bourville High in-First Conditions Permit Round Battles DR. PITTMAN SPEAKER FAVORABLE REPORT STRESS FUNDAMENTALS FINALS SATURDAY NITE According to Information released Having recently returned from the today by Dr. W. C. Jones, head of meeting of the American Associa- Uniforms were issued to some 45 None of the teams meeting In the department of research here, tion of Teachers Colleges, in which Eastern gridiron candidates and Eastern will be host March 23 and the first round of the Thirteenth Eastern has membership, held Feb- spring football practice got under Regional basketball tournament, to 24 to a conference of county super- ruary 23 and 24, in Minneapolis, way Tuesday afternoon. -

The Montana Kaimin, February 19, 1932

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 2-19-1932 The onM tana Kaimin, February 19, 1932 Associated Students of the State University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the State University of Montana, "The onM tana Kaimin, February 19, 1932" (1932). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 1337. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/1337 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA, MISSOULA, MONTANA FRIDAY. FEBRUARY 19. 1932 VOLUME XXXI. No. 35 IONTANA Masquers Will Present Alumni Present Open Rate Is Given FIRST CONVOCATION IU 8 I NQ8 “Death Takes a Holiday” Tentative Plans To Interscholastic For June Reunion Every Railroad In State Will Have OF YEAR WILL OPEN As Major Play Tonight\ One-Way Fare for Track Meet Interfraternity Members Are Urged To Arrange Programs Word was received yesterday by Dr. LOCAL CELEBRATION Proceeds From Presentation Will Go to Alnmni Association to Help i Eliminating Conflicts J. P. Rowe, chairman of the Inter