Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints Presentations University Libraries 5-2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Maggie Mason Smith Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Mason Smith, Maggie, "Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display" (2017). Presentations. 105. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/lib_pres/105 This Display is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Presentations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display May 2017 Blockbusters: Films and the Books About Them Display Photograph taken by Micki Reid, Cooper Library Public Information Coordinator Display Description The Summer Blockbuster Season has started! Along with some great films, our new display features books about the making of blockbusters and their cultural impact as well as books on famous blockbuster directors Spielberg, Lucas, and Cameron. Come by Cooper throughout the month of May to check out the Star Wars series and Star Wars Propaganda; Jaws and Just When you thought it was Safe: A Jaws Companion; The Dark Knight trilogy and Hunting the Dark Knight; plus much more! *Blockbusters on display were chosen based on AMC’s list of Top 100 Blockbusters and Box Office Mojo’s list of All Time Domestic Grosses. - Posted on Clemson University Libraries’ Blog, May 2nd 2017 Films on Display • The Amazing Spider-Man. Dir. Marc Webb. Perf. Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Rhys Ifans. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

Any Gods out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 2 October 2003 Article 3 October 2003 Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek John S. Schultes Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Schultes, John S. (2003) "Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek Abstract Hollywood films and eligionr have an ongoing rocky relationship, especially in the realm of science fiction. A brief comparison study of the two giants of mainstream sci-fi, Star Wars and Star Trek reveals the differing attitudes toward religion expressed in the genre. Star Trek presents an evolving perspective, from critical secular humanism to begrudging personalized faith, while Star Wars presents an ambiguous mythological foundation for mystical experience that is in more ways universal. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 Schultes: Any Gods Out There? Science Fiction has come of age in the 21st century. From its humble beginnings, "Sci- Fi" has been used to express the desires and dreams of those generations who looked up at the stars and imagined life on other planets and space travel, those who actually saw the beginning of the space age, and those who still dare to imagine a universe with wonders beyond what we have today. -

S Ullivan This Page Intent

Studying Film S t u d y i n g t h e M e d i a S e r i e s G e n e r a l E d i t o r : T i m O ' S u l l i v a n This page intentionally left blank Studying Film Nathan Abrams (Wentworth College) Ian Bell (West Herts College) Jan Udris (Middlesex University and Birkbeck College) A member of the Hodder Headline Group LONDON Co-published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Inc., New York First published in Great Britain in 2001 by Arnold, a member of the Hodder Headline Group, 338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH http://www.arnoldpublishers.com Co-published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press Inc., 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY10016 © 2001 Nathan Abrams, Ian Bell and Jan Udris All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanically including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency: 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1POLP. The advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, but neither the authors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication -

LCCC Thematic List

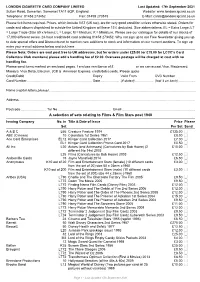

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, Et Al

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, et al. Summer Camp Scares I Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th I Still Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th Part 2 All The Boys Love Mandy Lane Friday the 13th Part III The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) Sleepaway Camp The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers House of Wax Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland Wolf Creek The Final Girls Wolf Creek 2 Stage Fright Psycho Beach Party The Burning Club Dread Campfire Tales Disturbia Addams Family Values It Follows The Devil’s Rejects Creepy Cabins in the Woods Blood Beach Cabin Fever The Lost Boys The Cabin in the Woods Straw Dogs The Evil Dead The Town That Dreaded Sundown Evil Dead 2 VACATION NIGHTMARES IT Evil Dead Hostel Ghost Ship Tucker and Dale vs Evil Hostel: Part II From Dusk till Dawn The Hills Have Eyes Death Proof Eden Lake Jeepers Creepers Funny Games Turistas Long Weekend AQUATIC HORROR, SHARKS, & ANIMAL ATTACKS Donkey Punch Jaws An American Werewolf in London Jaws 2 An American Werewolf in Paris Jaws 3 Prey Joyride Jaws: The Revenge Burning Bright The Hitcher The Reef Anaconda Borderland The Shallows Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid Tourist Trap 47 Meters Down Lake Placid I Spit On Your Grave Piranha Black Water Wrong Turn Piranha 3D Rogue The Green Inferno Piranha 3DD Backcountry The Descent Shark Night 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon Deliverance Bait 3D Jurassic Park High Tension Open Water The Lost World: Jurassic Park II Kalifornia Open Water 2: Adrift Jurassic Park III Open Water 3: Cage Dive Jurassic World Deep Blue Sea Dark Tide mrandmrshalloween.com. -

Wastewater Facility Plan (Sprenkle & Associates 2001) 2

January 14, 2016 Mr. Steve Walensky Director of Public Works City of Cassville 300 Main Street Cassville, Missouri 65625 Re: WASTEWATER COLLECTION SYSTEM FACILITY PLAN OA PROJECT NO. 014-2994 Dear Mr. Walensky, We present herewith a copy of the City of Cassville Wastewater Collection System Facility Plan, in accordance with our agreement dated July 31, 2014. This Facility Plan summarizes our evaluation of the City’s existing wastewater collection system with respect to the development of a comprehensive plan to guide collection system improvements to be pursued by the City over the next several years. Two copies of this report will be sent to MoDNR as part of the Small Community Engineering Assistance Grant requirements. We appreciate all of the assistance received from officials and employees of the City during the preparation of this Facility Plan. Sincerely, OLSSON ASSOCIATES Jerry Jesky, P.E. Senior Engineer Attachment 550 St. Louis Street TEL 417.890.8802 www.olssonassociates.com Springfield, MO 65806 FAX 417.890.8805 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 A. Purpose .................................................................................................................... 1 B. Scope ....................................................................................................................... 1 C. Existing Conditions .................................................................................................. -

A Critical Assessment of Virtual Reality Technologies for Modeling, Simulation, and Training

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 6-15-2021 The matrix revisited: A critical assessment of virtual reality technologies for modeling, simulation, and training George Demetrius Lecakes Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Lecakes, George Demetrius, "The matrix revisited: A critical assessment of virtual reality technologies for modeling, simulation, and training" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 2914. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2914 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MATRIX REVISITED: A CRITICAL ASSESSMENT OF VIRTUAL REALITY TECHNOLOGIES FOR MODELING, SIMULATION, AND TRAINING by George Demetrius Lecakes, Jr. A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Henry M. Rowan College of Engineering In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Rowan University March 5, 2021 Dissertation Chair: Shreekanth Mandayam, Ph.D. Committee Members: Nidhal Bouaynaya, Ph.D. John Schmalzel, Ph.D. Amanda Almon, M.F.A, C.M.I Ying (Gina) Tang, Ph.D. © 2021 George Demetrius Lecakes, Jr. Dedication I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my two sons, Georgie and Arthur. Acknowledgements The material within this dissertation took the better part of twenty years to complete, and there were many who helped along the way. First, I would like to acknowledge my advisor, Dr. -

Pdf, 328.81 KB

00:00:00 Oliver Wang Host Hi everyone. Before we get started today, just wanted to let you know that for the next month’s worth of episodes, we have a special guest co-host sitting in for Morgan Rhodes, who is busy with some incredible music supervision projects. Both Morgan and I couldn’t be more pleased to have arts and culture writer and critic, Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan. And if you recall, Ernest joined us back in 2017 for a wonderful conversation about Sade’s Love Deluxe; which you can find in your feed, in case you want to refamiliarize yourself with Ernest’s brilliance or you just want to listen to a great episode. 00:00:35 Music Music “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:41 Oliver Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:43 Ernest Host And I’m Ernest Hardy, sitting in for Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening Hardy to Heat Rocks. 00:00:47 Oliver Host Every episode we invite a guest to join us to talk about a heat rock. You know, an album that’s hot, hot, hot. And today, we will be taking a trip to Rydell High School to revisit the iconic soundtrack to the 1978 smash movie-musical, Grease. 00:01:02 Music Music “You’re The One That I Want” off the album Grease: The Original Soundtrack. Chill 1950s rock with a steady beat, guitar, and occasional piano. DANNY ZUKO: I got chills, they're multiplying And I'm losing control 'Cause the power you're supplying It's electrifying! [Music fades out as Oliver speaks] 00:01:20 Oliver Host I was in first grade the year that Grease came out in theaters, and I think one of the only memories I have about the entirety of first grade was when our teacher decided to put on the Grease soundtrack onto the class phonograph and play us “Grease Lightnin’”. -

Breaking the Code of the Matrix; Or, Hacking Hollywood

Matrix.mss-1 September 1, 2002 “Breaking the Code of The Matrix ; or, Hacking Hollywood to Liberate Film” William B. Warner© Amusing Ourselves to Death The human body is recumbent, eyes are shut, arms and legs are extended and limp, and this body is attached to an intricate technological apparatus. This image regularly recurs in the Wachowski brother’s 1999 film The Matrix : as when we see humanity arrayed in the numberless “pods” of the power plant; as when we see Neo’s muscles being rebuilt in the infirmary; when the crew members of the Nebuchadnezzar go into their chairs to receive the shunt that allows them to enter the Construct or the Matrix. At the film’s end, Neo’s success is marked by the moment when he awakens from his recumbent posture to kiss Trinity back. The recurrence of the image of the recumbent body gives it iconic force. But what does it mean? Within this film, the passivity of the recumbent body is a consequence of network architecture: in order to jack humans into the Matrix, the “neural interactive simulation” built by the machines to resemble the “world at the end of the 20 th century”, the dross of the human body is left elsewhere, suspended in the cells of the vast power plant constructed by the machines, or back on the rebel hovercraft, the Nebuchadnezzar. The crude cable line inserted into the brains of the human enables the machines to realize the dream of “total cinema”—a 3-D reality utterly absorbing to those receiving the Matrix data feed.[footnote re Barzin] The difference between these recumbent bodies and the film viewers who sit in darkened theaters to enjoy The Matrix is one of degree; these bodies may be a figure for viewers subject to the all absorbing 24/7 entertainment system being dreamed by the media moguls. -

SRI Grease 2

SRI Grease 2 High performance high temperature grease Product description Product highlights SRI Grease 2 is a high performance high temperature ball • Designed for use in a wide range of applications and roller bearing grease. It is dark green in colour and has a smooth, buttery structure. • Temperature range, from -20°C to +150°C • Formulated to offer robust oxidation stability SRI Grease 2 is formulated with highly refined base stocks, • Helps protect at high temperatures and speeds a high performance ashless organic polyurea thickener and robust anti-rust and anti-oxidation additives. • Provides rust protection as defined by ASTM D5969 Selected specification standards include: Customer benefits DIN 51 502 ISO 6743-9 • Designed for use in a wide range of high temperature, high speed applications helping reduce inventories and Schaeffler associated costs • Offers component protection across a wide operating temperature range, from as low as -20°C up to +150°C • Formulated to offer reliable long service oxidation stability, helping improve equipment performance and protection • Helps protect components at high temperatures, and speeds in excess of 10,000 rpm and where salt water ingress is possible • Provides rust protection as defined by ASTM D5969 helping provide longer bearing life in high speed, high temperature operations Always confirm that the product selected is consistent with the original equipment manufacturer’s recommendation for the equipment operating conditions and customer’s maintenance practices. SRI Grease 2 ─ Continued Applications SRI Grease 2 is recommended: Note that in today’s more modern, high output (horsepower), high load electric motors, there are times • for use in a wide range of automotive and industrial where these units employ ball bearings and roller applications element bearings on the same motor.