East Brother Light Station

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

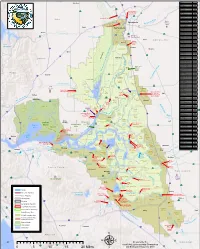

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

City of San Pablo Affordable Housing Strategy

CITY OF SAN PABLO AFFORDABLE HOUSING STRATEGY Prepared for: City of San Pablo November 9, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 Effects of COVID-19 on Housing Affordability ..................................................................................... 5 Process for Developing the AHS .......................................................................................................... 6 EXISTING CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................................... 8 Housing Supply ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Existing Housing Affordability Needs ............................................................................................... 15 Existing Resources, Policies, and Programs .................................................................................... 21 RESIDENTIAL MARKET CONDITIONS IN SAN PABLO ...................................................................... 27 Residential Market Supply and Trends ............................................................................................ 27 Opportunities and Constraints for Development ............................................................................ 34 OVERVIEW OF THE IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ................................................................................. -

Marin Islands NWR Sport Fishing Plan

Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 MARIN ISLANDS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE 3 SPORT FISHING PLAN 3 1. Introduction 3 2. Statement of Objectives 4 3. Description of the Fishing Program 5 A. Area to be Opened to Fishing 5 B. Species to be Taken, Fishing periods, Fishing Access 5 C. Fishing Permit Requirements 7 D. Consultation and Coordination with the State 7 E. Law Enforcement 7 F. Funding and Staffing Requirements 8 4. Conduct of the Fishing Program 8 A. Permit Application, Selection, and/or Registration Procedures (if applicable) 8 B. Refuge-Spec if ic Fishing Regulat ions 8 C. Relevant State Regulations 8 D. Other Refuge Rules and Regulations for Sport Fishing 8 5. Public Engagement 9 A. Outreach for Announcing and Publicizing the Fishing Program 9 B. Anticipated Public Reaction to the Fishing Program 9 C. How Anglers Will Be Informed of Relevant Rules and Regulations 9 6. Compatibility Determination 9 7. Literature Cited 9 List of Figures Figure 1. Proposed Sport Fishing Area Fishing…………………………………6 Marin Islands NWR Fishing Plan Page 2 MARIN ISLANDS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SPORT FISHING PLAN 1. Introduction National Wildlife Refuges are guided by the mission and goals of the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS), the purposes of an individual refuge, Service policy, and laws and international treaties. Relevant guidance includes the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, as amended by the National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997, Refuge Recreation Act of 1962, and selected portions of the Code of Federal Regulations and Fish and Wildlife Service Manual. -

Section 3.4 Biological Resources 3.4- Biological Resources

SECTION 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4- BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section discusses the existing sensitive biological resources of the San Francisco Bay Estuary (the Estuary) that could be affected by project-related construction and locally increased levels of boating use, identifies potential impacts to those resources, and recommends mitigation strategies to reduce or eliminate those impacts. The Initial Study for this project identified potentially significant impacts on shorebirds and rafting waterbirds, marine mammals (harbor seals), and wetlands habitats and species. The potential for spread of invasive species also was identified as a possible impact. 3.4.1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SETTING HABITATS WITHIN AND AROUND SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY The vegetation and wildlife of bayland environments varies among geographic subregions in the bay (Figure 3.4-1), and also with the predominant land uses: urban (commercial, residential, industrial/port), urban/wildland interface, rural, and agricultural. For the purposes of discussion of biological resources, the Estuary is divided into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay (See Figure 3.4-2). The general landscape structure of the Estuary’s vegetation and habitats within the geographic scope of the WT is described below. URBAN SHORELINES Urban shorelines in the San Francisco Estuary are generally formed by artificial fill and structures armored with revetments, seawalls, rip-rap, pilings, and other structures. Waterways and embayments adjacent to urban shores are often dredged. With some important exceptions, tidal wetland vegetation and habitats adjacent to urban shores are often formed on steep slopes, and are relatively recently formed (historic infilled sediment) in narrow strips. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall . -

2015-005890Des

Landmark Designation Case Report Hearing Date: October 5, 2016 Case No.: 2015-005890DES Project Address: 546-548 Fillmore Street, 554 Fillmore Street, 735 Fell Street, 660 Oak Street Zoning: RM-3 Residential-Mixed, Medium Density; RM-1 Residential- Mixed, Low Density Block/Lot: 0828/021, 0828/022, 0828/022A, 0828/012 Property Owner: Noe Vista LLC 3265 17th St., Ste. 403 San Francisco, CA 94110 554 Fillmore Street LLC 1760 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 Staff Contact: Shannon Ferguson – (415) 575-9074 [email protected] Reviewed By: Tim Frye – (415) 575-6822 [email protected] PROPERTY DESCRIPTION & SURROUNDING LAND USE AND DEVELOPMENT The Sacred Heart Parish Complex is situated on four contiguous lots on the city block bounded by Fillmore Street to the west, Fell Street to the north, Webster Street to the east, and Oak Street to the south in the Western Addition neighborhood, a largely residential neighborhood characterized by three and four story multi-family buildings. Sacred Heart Church (1898, 1909) is set at the southeast corner of Fillmore and Fell streets. Sacred Heart School (1926) is immediately east of the church on Fell Street. The rectory (ca. 1891, 1906) is immediately south of the church on Fillmore Street. The convent (1936) fronts Oak Street. An adjacent lot associated with the convent contains a paved parking area. The four lots converge in the center of the block to form an enclosed school yard. PROJECT DESCRIPTION The case before the Historic Preservation Commission is the consideration of the initiation of landmark designation of Sacred Heart Parish Complex as a San Francisco landmark under Article 10 of the Planning Code, Section 1004.1, and recommending that the Board of Supervisors approve of such designation. -

Farallon Islands and Noon Day Rock, Supports the Largest Seabird Nesting Colony South of Alaska

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Farallon National Wildlife Refuge Photo: ©PRBO Dense colonies of common murres and colorful puffins cloak cliff faces and crags, while two-ton elephant seals fight fierce battles for breeding sites on narrow wave-etched terraces below. Natural History Surrounded by cold water and plenty of food Pt. Reyes San Rafael G ulf o f Fa Golden ra ll Gate on s Bridge iles Oakland 28 M San Francisco C a li fo Fremont rn PACIFIC OCEAN ia San Jose Farallon National Wildlife Refuge, made up of all the Farallon Islands and Noon Day Rock, supports the largest seabird nesting colony south of Alaska. Thirteen seabird species numbering over 200,000 individuals Pigeon nest here each summer. Throughout the year, six species of marine mammals Guillemot breed or haul out on the islands. These islands are beside the cold California current which originates in Alaska and flows north to south, they are also surrounded Photo: © Brian O’Neil by waters of the Gulf of Farallons National Marine Sanctuary. Lying 28 miles west of San Francisco Bay the Refuge is on the western edge of the continental shelf. This area of Western gull the ocean plunges to 6,000 foot depths. Cold upwelling water brought from the depths as the wind blows surface water westward from the shoreline, and the California current flowing southward past the islands provides an ideal biological mixing zone along the continental shelf and around the San Francisco Bay area. Photos: © Brian O’Neil We stw ard Win ds Upwelling ent Mixing urr a C Deep rni lifo Ca Cold Water S N USGS Chart of seafloor Upwelling occurs notably in the spring depths around when these wind and water currents Farallon NWR work together and saturate ocean waters with nutrients brought up from Black the deep ocean. -

Park Report Part 1

Alcatraz Island Golden Gate National Recreation Area Physical History PRE-EUROPEAN (Pre-1776) Before Europeans settled in San Francisco, the area was inhabited by Native American groups including the Miwok, in the area north of San Francisco Bay (today’s Marin County), and the Ohlone, in the area south of San Francisco Bay (today’s San Francisco peninsula). Then, as today, Alcatraz had a harsh environment –strong winds, fog, a lack of a fresh water source (other than rain or fog), rocky terrain –and there was only sparse vegetation, mainly grasses. These conditions were not conducive to living on the island. These groups may have used the island for a fishing station or they may have visited it to gather seabird eggs since the island did provide a suitable habitat for colonies of seabirds. However, the Miwok and Ohlone do not appear to have lived on Alcatraz or to have visibly altered its landscape, and no prehistoric archeological sites have been identified on the island. (Thomson 1979: 2, Delgado et al. 1991: 8, and Hart 1996: 4). SPANISH AND MEXICAN PERIOD (1776-1846) Early Spanish explorers into Alta California encountered the San Francisco Bay and its islands. (Jose Francisco Ortega saw the bay during his scouting for Gaspar de Portola’s 1769 expedition, and Pedro Fages described the three major islands –Angel, Alcatraz, and Yerba Buena –in his journal from the subsequent 1772 expedition.) However, the first Europeans to record their visit to Alcatraz were aboard the Spanish ship San Carlos, commanded by Juan Manuel de Ayala that sailed through the Golden Gate and anchored off Angel Island in August 1775. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The purpose of this book is twofold: to provide general information for anyone interested in the California islands and to serve as a field guide for visitors to the islands. The book covers both general history and nat- ural history, from the geological origins of the islands through their aboriginal inhabitants and their marine and terrestrial biotas. Detailed coverage of the flora and fauna of one island alone would completely fill a book of this size; hence only the most common, most readily observed, and most interesting species are included. The names used for the plants and animals discussed in this book are the most up-to-date ones available, based on the scientific literature and the most recently published guidebooks. Common names are always subject to local variations, and they change constantly. Where two names are in common use, they are both mentioned the first time the organism is discussed. Ironically, in recent years scientific names have changed more recently than common names, and the reader concerned about a possible discrepancy in nomenclature should consult the scientific literature. If a significant nomenclatural change has escaped our notice, we apologize. For plants, our primary reference has been The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, edited by James C. Hickman, including the latest lists of errata. Variation from the nomenclature in that volume is due to more recent interpretations, as explained in the text. Certain abbreviations used throughout the text may not be immedi- ately familiar to the general reader; they are as follows: sp., species (sin- gular); spp., species (plural); n. -

Shark Encounters, Cage Diving in the Farallon Islands, California

One Day Dive Adventures The Farallon Islands Our Shark Team “The Devil’s Teeth” When you join us for a Great White Shark Our Incredible Great White Shark Adventures depart adventure to San Francisco’s Farallon from San Francisco’s famous Fisherman’s Wharf. Islands, you’ll find yourself in very good hands. We’re proud of our staff and when you dive with You’ll need to be at the dock by 6:00 am to get checked us, you’ll understand why. Here are just two of in and ready for a prompt 6:30-7:00 am departure. Total the great people you may meet: time at the dive site varies, but expect to be back at the dock between 5-6 pm. A continental breakfast, hot Greg Barron is our Director of West Coast Shark lunch and beverages are provided for you. Our boat is Ops. Greg has spent his entire life living and div- equipped to handle 12 divers and 6 topside viewers in ing along the North Coast of California and has comfort. been part of our shark dive operation since the beginning. Greg helped the great Located roughly 20 miles off the coast of San people at DOER Marine Cage Dives: $875 Top Side Viewing: $ 375 Francisco is a series of land formations known design and build our as the Farallon Islands. The islands lie within massive shark cage and the Gulf of the Farallones Marine Sanctuary, has worked to transform Full payment is required the day you book your dive and 1255 square miles of protected waters deemed our boat into an incredible is NON-REFUNDABLE.