Russian Literature in the Christian Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian (RUS) 1

Russian (RUS) 1 RUSSIAN (RUS) RUS 53: Intermediate Intensive Russian for Graduate Students 3 Credits RUS 1: Elementary Russian I Continued intensive study of Russian at the intermediate level: reading, 4 Credits writing, speaking, listening, cultural contexts. RUS 053 Intermediate Intensive Russian for Graduate Students (3)This is the third in a series Audio-lingual approach to basic Russian; writing. Students who have of three courses designed to give students an intermediate intensive received high school credit for two or more years of Russian may not knowledge of Russian. Continued intensive study of Russian at the schedule this course for credit, without the permission of the department. intermediate level: reading, writing, speaking, listening, and cultural contexts. Lessons are taught in an authentic cultural context. Bachelor of Arts: 2nd Foreign/World Language (All) Prerequisite: RUS 052 or equivalent, and graduate standing RUS 2: Elementary Russian II 4 Credits RUS 83: First-Year Seminar in Russian Audio-lingual approach to basic Russian continued; writing. Students 3 Credits who have received high school credit for four years of Russian may not schedule this course for credit, without the permission of the department. Russia's cultural past and present. RUS 083S First-Year Seminar in Russian (3) (GH;FYS;US;IL)(BA) This course meets the Bachelor of Arts Prerequisite: RUS 001 degree requirements.Russia, the world's largest country stretching Bachelor of Arts: 2nd Foreign/World Language (All) over eleven time zones in Europe and Asia, is currently undergoing a dramatic transformation. For the past hundred years, Russia has RUS 3: Intermediate Russian served as a laboratory of gigantic dimensions as various social ideals 4 Credits were implemented with unprecedented radicalism. -

"Russian Idea" of F.M. Dostoevsky: from Soilness to Universality

RUDN Journal of Philosophy 2021 Vol. 25 No. 1 15—24 Âåñòíèê ÐÓÄÍ. Ñåðèÿ: ÔÈËÎÑÎÔÈß http://journals.rudn.ru/philosophy DOI: 10.22363/2313-2302-2021-25-1-15-24 Research Article / Научная статья "Russian Idea" of F.M. Dostoevsky: from Soilness to Universality Sergei A. Nizhnikov Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 6, Miklukho-Maklaya St., Moscow, 117198, Russian Federation, [email protected] Abstract. The author reveals Fyodor Dostoevsky's works main features, his importance for Russian and world philosophy. The researcher analyzes the concept of "Russian Idea" introduced by Dostoyevsky, which became a study subject in Russian philosophy's subsequent history. The polemics that arose regarding the characteristics of Dostoevsky's soilness (Pochvennichestvo) ideology and his interpretation of the Russian Idea in his Pushkin Speech and subsequent comments in A Writer's Diary are unveiled. The author concludes that Dostoevsky overcomes the limitations of soilness and comes to universalism. The universal for him does not have a rootless cosmopolitan character but is born from the national's heyday. Diversity adorns the truth, and national diversity enamels humankind. People's real unity is in that all-human value that is found in the highest examples of each national culture. The truth is not in rootless cosmopolitanism or nationalism — it is in the "golden mean," which, in our opinion, the writer-philosopher sought to express. Dostoevsky wanted to rise above the dispute, to recognize the points of view of the Slavophiles and Westernizers as one-sided, to get out of any particularity to universality. Keywords: Dostoevsky, Russian idea, soilness, universality, anthropology of hesychasm, all-human, nationality Funding and Acknowledgement of Sources. -

Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Russian Faculty Research and Scholarship Russian 2009 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs Custom Citation Harte, Tim. "Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports," Nabokov Studies 12.1 (2009): 147-166. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College Dec. 2012 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports “People have played for as long as they have existed,” Vladimir Nabokov remarked in 1925. “During certain eras—holidays for humanity—people have taken a particular fancy to games. As it was in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, so it is in our present-day Europe” (“Braitenshtreter – Paolino,” 749). 1 For Nabokov, foremost among these popular games were sports competitions. An ardent athlete and avid sports fan, Nabokov delighted in the competitive spirit of athletics and creatively explored their aesthetic as well as philosophical ramifications through his poetry and prose. As an essential, yet underappreciated component of the Russian-American writer’s art, sports appeared first in early verse by Nabokov before subsequently providing a recurring theme in his fiction. The literary and the athletic, although seemingly incongruous modes of human activity, frequently intersected for Nabokov, who celebrated the thrills, vigor, and beauty of sports in his present-day “holiday for humanity” with a joyous energy befitting such physical activity. -

Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Senior Honors Theses Undergraduate Showcase 12-2017 Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity Monica Hanson-Green University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Hanson-Green, Monica, "Russian Foreign Policy and National Identity" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 99. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses/99 This Honors Thesis-Restricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Honors Thesis-Restricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Honors Thesis-Restricted has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY AND NATIONAL IDENTITY An Honors Thesis Presented to the Program of International Studies of the University of New Orleans In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts, with University High Honors and Honors in International Studies By Monica Hanson-Green December 2017 Advised by Dr. Michael Huelshoff ii Table of Contents -

The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature

Hamren 1 The Eternal Stranger: The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Kelly Hamren 4 May 2011 Hamren 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English Dr. Carl Curtis ____________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Emily Heady ____________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Thomas Metallo ____________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Hamren 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who have seen me through this project and, through support for my academic endeavors, have made it possible for me to come this far: to Dr. Carl Curtis, for his insight into Russian literature in general and Dostoevsky in particular; to Dr. Emily Heady, for always pushing me to think more deeply about things than I ever thought I could; to Dr. Thomas Metallo, for his enthusiastic support and wisdom in sharing scholarly resources; to my husband Jarl, for endless patience and sacrifices through two long years of graduate school; to the family and friends who never stopped encouraging me to persevere—David and Kathy Hicks, Karrie Faidley, Jennifer Hughes, Jessica Shallenberger, and Ramona Myers. Hamren 4 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chapter 2: Epiphany and Alienation...................................……………………………………...26 Chapter 3: “Yes—Feeling Early Cooled within Him”……………………………..……………42 Chapter 4: A Soul not Dead but Dying…………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 5: Where There’s a Will………………………………………………………………...96 Chapter 6: Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..130 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….134 Hamren 5 Introduction The superfluous man is one of the most important developments in the Golden Age of Russian literature—the period beginning in the 1820s and climaxing in the great novels of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. -

Christian Mission in a Russian Orthodox Context

EAST -WE ST CHUR C H MINISTRY RE PORT &FALL 2014 Vol. 22, No. 4 Christian Mission in a Russian Orthodox Context Walter Sawatsky Christian mission in Orthodox lands is a 2000- significantly different church-state experiences of year-old story, generally unknown in the West Orthodox and evangelicals during the Soviet era. and still unexplored sufficiently for the purpose of Perhaps the most profound difference was that Contributing Editors Christian mission in post-Communist states. Because following the October Revolution, the first action Canon Michael Bourdeaux of Orthodox repression under Islamic and Soviet of Soviet authorities was to declare the separation Keston Institute, overlords, and a stifling tsarist bear hug in between, of the churches from the state. The new regime also Oxford public perception has not yet perceived Orthodoxy as refused the legal right of juridical personhood to all a missionary church. religious bodies, including the newly established Dr. Anita Deyneka Russian Patriarchate, calling into question the future Peter Deyneka Russian The Babylonian Captivity Even if the Russian Orthodox Mission Society, of all organized religious life. Orthodox experienced Ministries, the first decade of Soviet power as an outright Wheaton, Illinois founded in 1865, achieved impressive results in the spread of Christianity across major tribal peoples of war on the church, specifically the destruction of Father Georgi Edelstein Siberia and in East Asia, Russian Orthodox leadership Orthodox institutions, until in 1927 acting patriarch Russian Orthodox Church, came to refer to the period from 1721 to 1917 as the Sergei declared full loyalty to Soviet power without Kostroma Diocese era of the “Babylonian Captivity.” As a modernizing reservation. -

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia Through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises Through Art

Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography by Ihar Maslenikau B.A., Minsk, 1991 Extended Essays Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Ihar Maslenikau 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2015 Approval Name: Ihar Maslenikau Degree: Master of Arts Title: Understanding the Roots of Collectivism and Individualism in Russia through an Exploration of Selected Russian Literature - and - Spiritual Exercises through Art. Understanding of Reverse Perspective in Old Russian Iconography Examining Committee: Chair: Gary McCarron Associate Professor, Dept. of Communication Graduate Chair, Graduate Liberal Studies Program Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor Professor Emeritus Humanities and English Heesoon Bai Supervisor Professor Faculty of Education Paul Crowe External Examiner Associate Professor Humanities and Asia-Canada Program Date Defended/Approved: November 25, 2015 ii Abstract The first essay is a sustained reflection on and response to the question of why the notion of collectivism and collective coexistence has been so deeply entrenched in the Russian society and in the Russian psyche and is still pervasive in today's Russia, a quarter of a century after the fall of communism. It examines the development of ideas of collectivism and individualism in Russian society, focusing on the cultural aspects based on the examples of selected works from Russian literature. It also searches for the answers in the philosophical works of Vladimir Solovyov, Nicolas Berdyaev and Vladimir Lossky. -

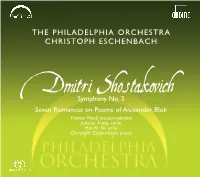

Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No

Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 1 THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA CHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH Dmitri Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances on Poems of Alexander Blok Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano Juliette Kang,violin Hai-Ye Ni,cello CHristoph EschenbacH,piano Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 2 ESCHENBACH CHRISTOPH • ORCHESTRA H bac hen c s PHILADELPHIA E THE oph st i r H C 2 Booklet_ODE1109 sos 3 10/01/08 13:35 Page 3 Dmitri ShostakovicH (1906–1975) Symphony No. 5 Seven Romances in D minor,Op. 47 (1937) on Poems of Alexander Blok,Op. 127 (1967) ESCHENBACH 1 I.Moderato – Allegro 5 I.Ophelia’s Song 3:01 non troppo 17:37 6 II.Gamayun,Bird of Prophecy 3:47 2 II.Allegretto 5:49 7 III.THat Troubled Night… 3:22 3 III.Largo 16:25 8 IV.Deep in Sleep 3:05 4 IV.Allegro non troppo 12:23 9 V.The Storm 2:06 bu VI.Secret Signs 4:40 CHRISTOPH • bl VII.Music 5:36 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yvonne Naef,mezzo-soprano CHristoph EschenbacH,conductor Juliette Kang,violin* Hai-Ye Ni ,cello* CHristoph EschenbacH ,piano ORCHESTRA *members of The Philadelphia Orchestra [78:15] Live Recordings:Philadelphia,Verizon Hall,September 2006 (Symphony No. 5) & Perelman Theater,May 2007 (Seven Romances) Executive Producer:Kevin Kleinmann Recording Producer:MartHa de Francisco Balance Engineer and Editing:Jean-Marie Geijsen – PolyHymnia International Recording Engineer:CHarles Gagnon Musical Editors:Matthijs Ruiter,Erdo Groot – PolyHymnia International PHILADELPHIA Piano:Hamburg Steinway prepared and provided by Mary ScHwendeman Publisher:Boosey & Hawkes Ondine Inc. -

Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde

87T" ACSA ANNUAL MEETING 125 Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde ELIZABETH C. ENGLISH University of Pennsylvania THE CONTEXT OF THE DEBATES BETWEEN Gogol and Nikolai Nadezhdin looked for ways for architecture to THE WESTERNIZERS AND THE SLAVOPHILES achieve unity out of diverse elements, such that it expressed the character of the nation and the spirit of its people (nnrodnost'). In the teaching of Modernism in architecture schools in the West, the Theories of art became inseparably linked to the hotly-debated historical canon has tended to ignore the influence ofprerevolutionary socio-political issues of nationalism, ethnicity and class in Russia. Russian culture on Soviet avant-garde architecture in favor of a "The history of any nation's architecture is tied in the closest manner heroic-reductionist perspective which attributes Russian theories to to the history of their own philosophy," wrote Mikhail Bykovskii, the reworking of western European precedents. In their written and Nikolai Dmitriev propounded Russia's equivalent of Laugier's manifestos, didn't the avantgarde artists and architects acknowledge primitive hut theory based on the izba, the Russian peasant's log hut. the influence of Italian Futurism and French Cubism? Imbued with Such writers as Apollinari Krasovskii, Pave1 Salmanovich and "revolutionary" fervor, hadn't they publicly rejected both the bour- Nikolai Sultanov called for "the transformation. of the useful into geois values of their predecessors and their own bourgeois pasts? the beautiful" in ways which could serve as a vehicle for social Until recently, such writings have beenacceptedlargelyat face value progress as well as satisfy a society's "spiritual requirements".' by Western architectural historians and theorists. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917

An Old Believer ―Holy Moscow‖ in Imperial Russia: Community and Identity in the History of the Rogozhskoe Cemetery Old Believers, 1771 - 1917 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Thomas De Simone, B.A., M.A Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Nicholas Breyfogle, Advisor David Hoffmann Robin Judd Predrag Matejic Copyright by Peter T. De Simone 2012 Abstract In the mid-seventeenth century Nikon, Patriarch of Moscow, introduced a number of reforms to bring the Russian Orthodox Church into ritualistic and liturgical conformity with the Greek Orthodox Church. However, Nikon‘s reforms met staunch resistance from a number of clergy, led by figures such as the archpriest Avvakum and Bishop Pavel of Kolomna, as well as large portions of the general Russian population. Nikon‘s critics rejected the reforms on two key principles: that conformity with the Greek Church corrupted Russian Orthodoxy‘s spiritual purity and negated Russia‘s historical and Christian destiny as the Third Rome – the final capital of all Christendom before the End Times. Developed in the early sixteenth century, what became the Third Rome Doctrine proclaimed that Muscovite Russia inherited the political and spiritual legacy of the Roman Empire as passed from Constantinople. In the mind of Nikon‘s critics, the Doctrine proclaimed that Constantinople fell in 1453 due to God‘s displeasure with the Greeks. Therefore, to Nikon‘s critics introducing Greek rituals and liturgical reform was to invite the same heresies that led to the Greeks‘ downfall. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57