Replication: Why We Still Can't Browse in Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Uniqueness of Browser Extensions and Web Logins

To Extend or not to Extend: on the Uniqueness of Browser Extensions and Web Logins Gábor György Gulyás Dolière Francis Somé INRIA INRIA [email protected] [email protected] Nataliia Bielova Claude Castelluccia INRIA INRIA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT shown that a user’s browser has a number of “physical” charac- Recent works showed that websites can detect browser extensions teristics that can be used to uniquely identify her browser and that users install and websites they are logged into. This poses sig- hence to track it across the Web. Fingerprinting of users’ devices is nificant privacy risks, since extensions and Web logins that reflect similar to physical biometric traits of people, where only physical user’s behavior, can be used to uniquely identify users on the Web. characteristics are studied. This paper reports on the first large-scale behavioral uniqueness Similar to previous demonstrations of user uniqueness based on study based on 16,393 users who visited our website. We test and their behavior [23, 50], behavioral characteristics, such as browser detect the presence of 16,743 Chrome extensions, covering 28% settings and the way people use their browsers can also help to of all free Chrome extensions. We also detect whether the user is uniquely identify Web users. For example, a user installs web connected to 60 different websites. browser extensions she prefers, such as AdBlock [1], LastPass [14] We analyze how unique users are based on their behavior, and find or Ghostery [8] to enrich her Web experience. Also, while brows- out that 54.86% of users that have installed at least one detectable ing the Web, she logs into her favorite social networks, such as extension are unique; 19.53% of users are unique among those who Gmail [13], Facebook [7] or LinkedIn [15]. -

Install and Configure Cisco Anyconnect VPN

Install and Configure Cisco AnyConnect VPN PURPOSE: • Installing and configuring Cisco AnyConnect • Enabling and Disabling Cisco AnyConnect VERSION SUPPORTED: 4.5.02033 HOW TO INSTALL AND CONFIGURE CISCO ANYCONNECT VPN FOR WINDOWS: From the desktop, open up a web browser (Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft Edge, or Internet Explorer). Note: Google Chrome will be used in this example. Type in vpn01.cu.edu into the address bar. You will reach a login page, login using your CU System Username and Password. Contact UIS Call: 303-860-4357 Email:[email protected] Click on the AnyConnect button on the bottom of the list on the left-hand side. Select the “Start AnyConnect” button on that page. It will then load a few items, after it finishes click the blue link for “AnyConnect VPN” Contact UIS Call: 303-860-4357 Email:[email protected] This will download the client in the web browser, in Google Chrome this shows up on the bottom section of the page, but other browsers may place the download in a different location. If you cannot find the download, it should go to the Downloads folder within Windows. Contact UIS Call: 303-860-4357 Email:[email protected] We will then run this download by clicking on it in Chrome. Other browsers may offer a “Run” option instead, which acts the same. It will then open up an installer. Click “Next.” Select the “I accept the terms in the License Agreement” button. Click “Next.” Contact UIS Call: 303-860-4357 Email:[email protected] Select “Install”, this will require the username and password you use to login to your personal computer. -

Machine Learning in the Browser

Machine Learning in the Browser The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811507 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Machine Learning in the Browser a thesis presented by Tomas Reimers to The Department of Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the subject of Computer Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2017 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Background . .3 1.2 Motivation . .4 1.2.1 Privacy . .4 1.2.2 Unavailable Server . .4 1.2.3 Simple, Self-Contained Demos . .5 1.3 Challenges . .5 1.3.1 Performance . .5 1.3.2 Poor Generality . .7 1.3.3 Manual Implementation in JavaScript . .7 2 The TensorFlow Architecture 7 2.1 TensorFlow's API . .7 2.2 TensorFlow's Implementation . .9 2.3 Portability . .9 3 Compiling TensorFlow into JavaScript 10 3.1 Motivation to Compile . 10 3.2 Background on Emscripten . 10 3.2.1 Build Process . 12 3.2.2 Dependencies . 12 3.2.3 Bitness Assumptions . 13 3.2.4 Concurrency Model . 13 3.3 Experiences . 14 4 Results 15 4.1 Benchmarks . 15 4.2 Library Size . 16 4.3 WebAssembly . 17 5 Developer Experience 17 5.1 Universal Graph Runner . -

![Browser Versions Carry 10.5 Bits of Identifying Information on Average [Forthcoming Blog Post]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0737/browser-versions-carry-10-5-bits-of-identifying-information-on-average-forthcoming-blog-post-190737.webp)

Browser Versions Carry 10.5 Bits of Identifying Information on Average [Forthcoming Blog Post]

Browser versions carry 10.5 bits of identifying information on average [forthcoming blog post] Technical Analysis by Peter Eckersley This is part 3 of a series of posts on user tracking on the modern web. You can also read part 1 and part 2. Whenever you visit a web page, your browser sends a "User Agent" header to the website saying what precise operating system and browser you are using. We recently ran an experiment to see to what extent this information could be used to track people (for instance, if someone deletes their browser cookies, would the User Agent, alone or in combination with some other detail, be enough to re-create their old cookie?). Our experiment to date has shown that the browser User Agent string usually carries 5-15 bits of identifying information (about 10.5 bits on average). That means that on average, only one person in about 1,500 (210.5) will have the same User Agent as you. On its own, that isn't enough to recreate cookies and track people perfectly, but in combination with another detail like an IP address, geolocation to a particular ZIP code, or having an uncommon browser plugin installed, the User Agent string becomes a real privacy problem. User Agents: An Example of Browser Characteristics Doubling As Tracking Tools When we analyse the privacy of web users, we usually focus on user accounts, cookies, and IP addresses, because those are the usual means by which a request to a web server can be associated with other requests and/or linked back to an individual human being, computer, or local network. -

Marcia Knous: My Name Is Marcia Knous

Olivia Ryan: Can you just state your name? Marcia Knous: My name is Marcia Knous. OR: Just give us your general background. How did you come to work at Mozilla and what do you do for Mozilla now? MK: Basically, I started with Mozilla back in the Netscape days. I started working with Mozilla.org shortly after AOL acquired Netscape which I believe was in like the ’99- 2000 timeframe. I started working at Netscape and then in one capacity in HR shortly after I moved working with Mitchell as part of my shared responsibility, I worked for Mozilla.org and sustaining engineering to sustain the communicator legacy code so I supported them administratively. That’s basically what I did for Mozilla. I did a lot of I guess what you kind of call of blue activities where we have a process whereby people get access to our CVS repository so I was the gatekeeper for all the CVS forms and handle all the bugs that were related to CVS requests, that kind of thing. Right now at Mozilla, I do quality assurance and I run both our domestic online store as well as our international store where we sell all of our Mozilla gear. Tom Scheinfeldt: Are you working generally alone in small groups? In large groups? How do you relate to other people working on the project? MK: Well, it’s a rather interesting project. My capacity as a QA person, we basically relate with the community quite a bit because we have a very small internal QA organization. -

Website Error Messages

Website Error Messages CO with a white page or 429 – Too many requests From time to time you may experience one of these login errors. CO with a white page This error occurs due to overloading. Please try again by clicking the back button or going to the web page again. You may need to try again more than once. If this doesn’t work, try the 429 instructions below. 429 – Too many requests The 429 issue is caused by cookies and web history that web browsers e.g. Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Firefox, Edge track. If you get either of these error pages you will need to clear your web browsing history and cookies. Please view the videos below to take you through this process (you can skip any advertisements). It is really easy to do and only takes a few seconds. Because you are deleting your webpage history and files that websites use to make access quicker to their websites, we suggest you clear the history for the last 7 days (or similar period - if this is an option) first. If you still get one of the login error messages: try clearing the history for the last 4 weeks, or as a last resort ‘All time’. Deleting the history will not harm your computer, but you may need to re-enter some passwords when you next visit some sites. Not sure what web browser you are using? Simply right click on the icon that you use to open your browser. This should show the browser name. Google Chrome https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQaUrLhxZJ0 Firefox/Mozilla https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=foMbKtIFaVs Microsoft Edge https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqlbvDFfXtw Apple/Mac Safari https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mY-keJ3xqhk Once you have deleted the history try logging into the NZCCA website again. -

How to Check Your Browser Version on a PC

How to Check Your Browser Version on a PC Google Chrome (PC) 1) Click on the Menu Icon ( ) in the upper right corner of your browser window. 2) Click on Settings 3) Click on the About tab on the left-hand side of the page. 4) If you are not running the most recent version of Chrome available for your Operating System, you will be prompted to update Chrome. For your security, we recommend that you install all Security, App and Operating System updates as they become available. Mozilla Firefox (PC) 1) Click on the Help menu at the top of your browser window. 2) Click on About Firefox at the bottom of the menu. 3) A small window will pop up showing your Firefox version number, and will tell you whether you are on the most recent version, or not. For your security, we recommend that you install all Security, App and Operating System updates as they become available. Internet Explorer (PC) 1) Click on the Gear Icon at the top of your browser window. 2) Click on the About Internet Explorer option. 3) A window will pop up showing you your Internet Explorer version. 4) If you are using Internet Explorer 9 or 10, you will need to make sure that you have TLS 1.2 enabled by: A) Clicking on the Gear Icon again. B) Click on Internet Options. C) Click on the Advanced Tab and scroll down to the option titled “Use TLS 1.2”. (This should be found at the bottome of the list of options.) The box next to this should be checked. -

Internal Message

Earlier today, Mozilla Corporation CEO and Mozilla Foundation Chairwoman Mitchell Baker sent the following message to Mozilla employees. We are making significant changes at Mozilla Corporation today. Pre-COVID, our plan for 2020 was a year of change: building a better internet by accelerating product value in Firefox, increasing innovation, and adjusting our finances to ensure financial stability over the long term. We started with immediate cost-saving measures such as pausing our hiring, reducing our wellness stipend and cancelling our All-Hands. But COVID-19 has accelerated the need and magnified the depth for these changes. Our pre-COVID plan is no longer workable. We have talked about the need for change — including the likelihood of layoffs — since the spring. Today these changes become real. We are also restructuring to put a crisper focus on new product development and go to market activities. In the long run, I am confident that the new organizational structure will serve our product and market impact goals well, but we will talk in detail about this in a bit. But, before that is the painful part. Yes — we need to reduce the size of our workforce. This is hard to internalize and I desperately wish there was some other way to set Mozilla up for success in building a better internet. I desperately wish that all those who choose Mozilla as an employer could stay as long as interest and skills connect. Unfortunately, we can’t make that happen today. We are reducing the size of the MoCo workforce by approximately 250 roles, including closing our current operations in Taipei, Taiwan. -

Accessing Your Check Point VPN Security

City of Philadelphia OIT—Information Accessing your Check Point VPN Security NOTE: The VPN only provides remote access to the Table of Contents network, any required native applications will need to be compatible with your local system. Internet Explorer Instructions STEP 1 Pages 1-5 Open your Internet Explorer web browser and enter the URL: Mozilla Firefox https://remote.phila.gov Instructions Pages 6-12 Recommended Anti -Virus Clients Page 13 STEP 2 If you are using Internet Explorer you may be prompted to install the ’Check Point Deployment Agent’ from ’Check Point Software Technologies Ltd.’ Follow the instructions below. 1 2 Page 2 Accessing your Check Point VPN STEP 3 Install the Check Point Deployment Agent when prompted. STEP 4 Check Point will be ask if you trust the server for remote.phila.gov. Click Trust Server. Page 3 Accessing your Check Point VPN STEP 4 Check Point will now scan your computer for security threats and check if your computer’s anti-virus client is in compliance with the City of Philadelphia’s Information Security policies. Note: If the scan is taking a long time or does not finish, please close the browser window and begin the process again at Step 1. NOTE: If your Anti-Virus scan FAILS PROCEED to page 13 of this document to see the list of approved Check Point Anti-virus clients that will allow you to access your VPN! Page 4 Accessing your Check Point VPN STEP 5 If the scan is successfully completed, you will be navigated to the Sign In page. -

Features Guide [email protected] Table of Contents

Features Guide [email protected] Table of Contents About Us .................................................................................. 3 Make Firefox Yours ............................................................... 4 Privacy and Security ...........................................................10 The Web is the Platform ...................................................11 Developer Tools ..................................................................13 2 About Us About Mozilla Mozilla is a global community with a mission to put the power of the Web in people’s hands. As a nonprofit organization, Mozilla has been a pioneer and advocate for the Web for more than 15 years and is focused on creating open standards that enable innovation and advance the Web as a platform for all. We are committed to delivering choice and control in products that people love and can take across multiple platforms and devices. For more information, visit www.mozilla.org. About Firefox Firefox is the trusted Web browser of choice for half a billion people around the world. At Mozilla, we design Firefox for how you use the Web. We make Firefox completely customizable so you can be in control of creating your best Web experience. Firefox has a streamlined and extremely intuitive design to let you focus on any content, app or website - a perfect balance of simplicity and power. Firefox makes it easy to use the Web the way you want and offers leading privacy and security features to help keep you safe and protect your privacy online. Mozilla continues to move the Web forward by pioneering new open source technologies such as asm.js, Emscripten and WebAPIs. Firefox also has a range of amazing built-in developer tools to provide a friction-free environment for building Web apps and Web content. -

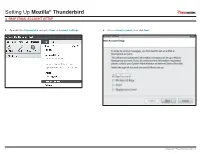

Setting up Mozilla® Thunderbird IMAP EMAIL ACCOUNT SETUP

Setting Up Mozilla® Thunderbird IMAP EMAIL ACCOUNT SETUP 1. Open Mozilla Thunderbird and go to Tools -> Account Settings. 2. Choose Email account; then click Next. 1 Copyright © EmailHosting.com LLC Setting Up Mozilla® Thunderbird IMAP EMAIL ACCOUNT SETUP (cont.) 3. In the Identity window type your name as you want it to appear on outgoing emails. 4. In the Server Information window select the radio button labeled IMAP. • Then, type your email address in the field labeled Email Address. • Enter imap.emailhosting.com in the field labeled Incoming Server. • Click Next to continue. • Enter smtp.emailhosting.com in the field labeled Outgoing Server. • Click Next to continue. John Smith imap.emailhosting.com [email protected] smtp.emailhosting.com Note: If you have already used Thunderbird in the past the Outgoing Server will not be listed. 2 Copyright © EmailHosting.com LLC Setting Up Mozilla® Thunderbird IMAP EMAIL ACCOUNT SETUP (cont.) 5. In the User Names window, the fields should already be filled out correctly. 6. Click Next on the Account Name page to accept the default Account Name. • Confirm that both fields match your EmailHosting username. • In the Congratulations window, verify that all information is correct. • Click Next to continue. • Then click Finish. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 7. You will be prompted for your password. If you’d like to save your password, make sure Use Password Manager to remember this password is checked before clicking on OK to continue. Note: The field Outgoing Server is only visible during the setup of Mozilla Thunderbird’s first email account. -

Examining Older Users' Online Privacy-Enhancing

EXAMINING OLDER USERS’ ONLINE PRIVACY-ENHANCING EXPERIENCE FROM A HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION PERSPECTIVE BY HSIAO-YING HUANG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Informatics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2019 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Assistant Professor Masooda Bashir, Chair Associate Professor Nikita Borisov Professor Wendy Rogers Professor Michael Twidale ABSTRACT The advancement of Internet technologies, including instant and unlimited access to information and services, has been an excellent source of support for older adults. However, pervasive and continuous online tracking can pose severe threats to older adults’ information privacy. Surprisingly, very few empirical studies have focused on older users’ online privacy-enhancing experience from a Human-Computer Interaction perspective. Therefore, it remains unclear how older users protect their online information privacy and what factors influence their online behaviors. Thus, my thesis aims to study older users’ online privacy-enhancing experience by examining the following questions: 1) what older users know and do to protect their online information privacy, 2) how their emotional state influences their adoption of privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs), and 3) what usability challenges they encounter while using one of the most popular PETs currently available to the public. To examine these questions, a diverse set of empirical approaches was adopted, including a survey, a quasi-experiment, and a usability study. My research findings suggest that three are three elements that play a crucial role in older users' online privacy-enhancing practices. First, older users' knowledge of online privacy has a significant influence on their daily online privacy protection behaviors.