Strong Links I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Student Directory

International Student Directory Giving links to various community groups and support organisations in the greater Wellington Region please visit: multiculturalnz.org.nz 1 Tertiary Providers (Universities and Technical Institutes) generally have significant support services and resources available within their own organisation. These services are specific to the institution and only available to students enrolled at that institution. However, some Tertiary information published is generic and may be helpful to the greater Providers international student community. NZQA Approved Wellington Tertiary Providers Provider Name Type Address Email Website Elite Management PTE Levels 3,4 & 6 [email protected] www.ems.ac.nz School Grand Central Tower 76 - 86 Manners St Wellington NZ Institute PTE NZIS Stadium Centre wellington@nzis. www.nzis.ac.nz of Sport Westpac Stadium ac.nz 105 Waterloo Quay Wellington NZ School of PTE Level 10, 57 Willis St [email protected] www.acupuncture. Acupuncture Wellington ac.nz and TCM NZ School PTE Te Whaea: dance@ www. of Dance National Dance and nzschoolofdance. nzschoolofdance. Drama Centre ac.nz ac.nz 11 Hutchison Rd Newtown, Wellington Te Kura Toi PTE Te Whaea: drama@toiwhakaari. www.toiwhakaari. Whakaari o National Dance and ac.nz ac.nz Aotearoa: Drama Centre NZ Drama School 11 Hutchison Rd Newtown, Wellington Te Rito Maioha: PTE Ground Floor studentservices@ www.ecnz.ac.nz Early Childhood 191 Thorndon Quay ecnz.ac.nz NZ Inc. Wellington The Learning PTE 182 Eastern Hutt Rd [email protected] www.tlc.ac.nz Connexion Ltd Taita, Lower Hutt 2 Provider Name Type Address Email Website The Salvation PTE 20 William Booth michelle_collins@ www.salvationarmy. -

Parish with a Mission by Geoff Pryor

Parish with a Mission By Geoff Pryor Foreword - The Parish Today The train escaping Wellington darts first into one tunnel and then into another long, dark tunnel. Leaving behind the bustle of the city, it bursts into a verdant valley and slithers alongside a steep banked but quiet stream all the way to Porirua. It hurtles through the Tawa and Porirua parishes before pulling into Paremata to empty its passengers on the southern outskirts of the Plimmerton parish. The train crosses the bridge at Paremata with Pauatahanui in the background. There is no sign that the train has arrived anywhere particularly significant. There is no outstanding example of engineering feat or architecture, no harbour for ocean going ships or airport. No university campus holds its youth in place. No football stadium echoes to the roar of the crowd. The whaling days have gone and the totara is all felled. Perhaps once Plimmerton was envisaged as the port for the Wellington region, and at one time there was a proposal to build a coal fired generator on the point of the headland. Nothing came of these ideas. All that passed us by and what we are left with is largely what nature intended. Beaches, rocky outcrops, cliffs, rolling hills and wooded valleys, magnificent sunsets and misted coastline. Inland, just beyond Pauatahanui, the little church of St. Joseph, like a broody white hen nestles on its hill top. Just north of Plimmerton, St. Theresa's church hides behind its hedge from the urgency of the main road north. The present day parish stretches in an L shape starting at Pukerua Bay through to Pauatahanui. -

2021 Plimmerton School (2960) Charter Approved

School Charter, Strategic & Annual Implementation Plan 2021 - 2023 March 2021 1 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Contents Introductory Section Description of the school 3 Major historical developments 4 Motto and mission 5 Vision 6 Values 7 Cultural diversity and Maori dimension 8 National Education and Learning Priorities 9 Strategic Plan Section Strategic Plan 2021-23 10 Annual Plan Section Refer to separate Annual plan spreadsheet APPROVED: March 2021 Page 2 Te Kura o Taupō Plimmerton School Description of the School Plimmerton School is a year 1 to 8 decile 10 school with a roll close to 500 students at the year end. The school includes 14% Maori students, 4% Pasific Peoples, 7% Asian, 73% NZ European, and 3% of other ethnic groups. Nestled in the coastal town of Plimmerton, north of Porirua city, we enjoy a unique combination of village community lifestyle, and the advantages of close proximity to city life. We are set 300m from the sea on a large site. Facilities include 23 classrooms, a field, a large hall/auditorium, a heated covered swimming pool, a technology centre, and a new library completed in 2020. Local iwi The original settlement of Hongoeka, today an active Ngati Toa marae with a wharenui, provides cultural richness and opportunity to the Plimmerton community. We share a close association with local iwi and Hongoeka, with a representative co-opted to the Board of Trustees. The school fosters participation and success of Maori students through Maori educational initiatives consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi such as the instruction in tikanga Maori and Te Reo Maori. -

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington

Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington This report has been prepared for Wellington City Council and is not intended for general publication or circulation. It is not to be reproduced without written agreement. We accept no responsibility to any party, unless specifically agreed by us in writing. We reserve the right, but will be under no obligation, to revise or amend our report in light of any additional information, which was in existence when the report was prepared, but which was not brought to our attention. Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Background 1. Background KPQ is strategically located in Ngauranga Gorge, on State Highway 1 within Wellington City. The quarry is a hard rock quarry extracting greywacke. The KPQ site also hosts: An asphalt plant owned and operated by Downer, and A concrete plant owned and operated by Allied Concrete in which Holcim has a 50% holding. There are long term supply agreements in place with these businesses which provide both long term stability and sales, with the advantage of having exposure to both roading and construction based sales. This provides balance if there are short term fluctuations in either market. There is reasonable ability to adjust production between either market. There are limited sources of aggregate material in the region. The greywacke rock resource reserves along the Wellington Fault have for many decades been the prime source of the hard rock quarried for use in the wider Wellington and Hutt Valley areas. Ngauranga Gorge has been quarried for over 100 years. 1920 Quarry activity in Ngauranga Gorge:Track & Stream (Alexander Turnbull Library) Regional Demand Forecasts for Aggregates in Wellington Regional Rock Resources and Alternatives 2. -

Caring Deception : Community Art in the Suburbs of Aotearoa

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Caring Deception: Community art in the suburbs of Aotearoa (New Zealand) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts at Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand. By Tim Barlow 2016 2 Abstract In Aotearoa (New Zealand), community art practice has a disadvantaged status and a poorly documented national history. This thesis reinvigorates the theory and practice of community art and cultural democracy using adaptable and context-specific analyses of the ways that aesthetics and ethics can usefully co-exist in practices of social change. The community art projects in this thesis were based in four suburbs lying on the economic and spatial fringes of Aotearoa. Over 4 years, I generated a comparative and iterative methodology challenging major binaries of the field, including: ameliorative vs. disruptive; coloniser vs. colonised; instrumental vs. instrumentalised; and long term vs. short term. This thesis asserts that these binaries create a series of impasses that drive the practice towards two new artistic categories, which I define as caring deception and the facade. All the projects I undertook were situated in contested space, where artists working with communities overlapped with local and national governments aiming for CBD and suburban re-vitalisation, creative city style initiatives, community development, grassroots creative projects, and curated public-art festivals. -

PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1

PLIMMERTON FARM – PLAN CHANGE PROPOSAL Supporting Documentation View from Submitters Property Karla and Trevor Beamsley 24 Motuhara Road Plimmerton PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION The village of Plimmerton is a northern suburb of Porirua, and is surrounded to the North and East by farmland. It represents the edge of existing residential dwellings. Generally existing homes are stand-alone dwellings on lots greater than 500m² in size. Most residents within Plimmerton and Camborne either commute into Wellington city or work from home. The demand for housing in this area is from professional couples or families looking for 3 – 4 bedroom family homes on a section with space for kids to run around in, not medium or high density three-storey buildings and apartments, this is reflected in the TPG report to PCC (Dec 2019). Medium density style townhouses, or apartments would be totally out of character of the surrounding residential areas, and would present a stark contrast to the remaining rural areas which bound the site. The Plimmerton Farm site is not located close to areas of high employment, nor is it close to local amenities like the main shopping areas of Porirua. The site is also not located within an area currently supported by existing infrastructure. Much of the infrastructure in the area is aging, and requires repair or upgrade to support existing demands. Therefore, the idea that Plimmerton Farm would provide homes in a location close to employment, amenities and infrastructure1 is simply incorrect in terms of a 10-year time frame. Areas where this would be true include the currently developing areas of Aotea, Whitby, Kenepuru, and Porirua East. -

Te Runanga O Toa Rangatira Inc Group

Te Runanga o Toa RangaTiRa inc Group 2018 ANNUAL REPORT (1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018) Upane ka upane whiti te ra Advancing together into a brighter future Moemoea Kia tu ai a Ngāti Toa Rangatira; Hei iwi Toa, hei iwi Rangatira Ngāti Toa is a strong, vibrant and influential Iwi, firmly grounded in our cultural identity and leading change to enable whanau wellbeing and prosperity CONTENTS 2 | Contents 3 | Executives, Directors, Trustees, Committees 4 | Chairman’s Report 6 | Executive Directors Report Pitopito Korero 8 | Administration / Communication 10 | Resource Management 11 | Toa Rangatira Education Achievement Team 12 | Te Puna Reo o Ngati Toa 15 | Te Puna Matauranga 18 | Disability Service 19 | Ora Toa Mauriora 24 | Ora Toa PHO Purongo Putea 25 | Te Runanga o Toa Rangatira Incorporated Group 66 | Toa Rangatira Trust Group 92 | Ora Toa PHO 108 | Ika Toa Limited 132 | Additional Financial Information 2 | W h ā r a n g i EXECUTIVES, DIRECTORS, TRUSTEES, COMMITTEES EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: TE AWARUA O PORIRUA AUDIT, RISK & INVESTMENT Matiu Rei WHAITUA COMMITTEE: COMMITTEE: Hikitia Ropata Miria Pomare, Chair BOARD / TRUSTEES Jennie Smeaton Caroline Taurima Taku Parai Elected – Chair Sharli Jo Solomon Francis Freemantle Helmut Modlik Willis Katene Elected – Deputy Ian Lyver Arthur Selwyn Takapuwahia Marae WHAITUA TE WHANGANUI-A- Kyle Edmonds Matthew Solomon Takapuwahia Marae TARA: Patariki Hippolite Whakatu Marae Matiu Rei Miria Pomare Hongoeka Marae Taku Parai NGATI TOA / RUNANGA Moana Parata Hongoeka Marae REPRESENTATIVES: Tracey Williams -

Historical Snapshot of Porirua

HISTORICAL SNAPSHOT OF PORIRUA This report details the history of Porirua in order to inform the development of a ‘decolonised city’. It explains the processes which have led to present day Porirua City being as it is today. It begins by explaining the city’s origins and its first settlers, describing not only the first people to discover and settle in Porirua, but also the migration of Ngāti Toa and how they became mana whenua of the area. This report discusses the many theories on the origin and meaning behind the name Porirua, before moving on to discuss the marae establishments of the past and present. A large section of this report concerns itself with the impact that colonisation had on Porirua and its people. These impacts are physically repre- sented in the city’s current urban form and the fifth section of this report looks at how this development took place. The report then looks at how legislation has impacted on Ngāti Toa’s ability to retain their land and their recent response to this legislation. The final section of this report looks at the historical impact of religion, particularly the impact of Mormonism on Māori communities. Please note that this document was prepared using a number of sources and may differ from Ngati Toa Rangatira accounts. MĀORI SETTLEMENT The site where both the Porirua and Pauatahanui inlets meet is called Paremata Point and this area has been occupied by a range of iwi and hapū since at least 1450AD (Stodart, 1993). Paremata Point was known for its abundant natural resources (Stodart, 1993). -

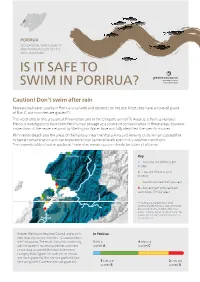

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site. -

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

Is it safe to swim in Porirua? Greater Wellington Regional Council and local councils monitor some of the Wellington region’s most popular beaches and rivers to determine their suitability for recreational activities such as swimming. We monitor eleven coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring are compared to national guidelines and used to calculate an overall grade for each site. Results from the 2014/15 summer season Recreational water quality in Porirua is quite variable with most sites having an overall grade of ‘C’. The best sites are at Karehana and Onehunga bays. These sites have an overall grade of ‘B’ and the Karehana Bay site met the guideline for safe swimming on all occasions. The worst sites were at the southern ends of Plimmerton Beach and Titahi Bay, and Te Awarua o Porirua Harbour at the Rowing Club. These sites recorded high bacterial counts on one occasion during the 2014/15 summer and have an overall grade of ‘D’. Very low risk of illness 0% Low risk 18% (2 sites) B Moderate risk 55% C (6 sites) Caution 27% (3 sites) D Unsuitable for swimming 0% In the Porirua area, 2 sites (18%) are graded ‘B’, 6 sites (55%) are graded ‘C’ and 3 sites (27%) are graded ‘D’. WAIT TWO DAYS AFTER RAIN before you swim again… Water quality at Porirua beaches is at its worst after heavy rain. Rain flushes contaminants from urban and rural land into water and we advise people not to swim for two days after heavy rain – even if a site generally has good water quality. -

Porirua – Our Place, Our Future, Our Challenge Let's Kōrero

COPYRIGHT © You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to Porirua City Council. Published March 2021. Porirua City Council 16 Cobham Court PO Box 50218 Porirua 5240 This document is available on our website poriruacity.govt.nz Porirua – our place, our future, our challenge Let’s kōrero Consultation Document for the proposed Long-term Plan 2021-51 Message from Ngāti Toa Rangatira E te iwi e noho nei i te riu o Porirua, tēnā koutou katoa The development of the city's Long-term Plan 2021-2051 will bring changes to our city that we will be proud of. Between now and 2051 we will see Porirua transform into a vibrant and exciting place to be for residents and people who choose to work here. We are blessed with hills, waterways, Te Mana o Kupe bushwalks and two magnificent harbours, Porirua and Pāuatahanui, as well as rich histories all anchored by Te Matahourua, the anchor left here by Kupe. As a challenge to all of us – we must look after our environment and look after each other, especially our tamariki and rangatahi. Nou te rourou, naku te rourou ka ora ai te Iwi With your contribution, and my contribution the people will thrive Taku Parai Chairman, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira 2 Consultation Document for the proposed LTP 2021-51 Contents Mai i tō Koutou Koromatua 4 From your Mayor Executive summary 8 Rates 10 The challenges for our city 11 Your views 16 Investment in the 3 waters – drinking water, wastewater 17 & stormwater 1. -

Porirua City Health and Disability Report and Plan

3RULUXD &LW\ +HDOWK DQG 'LVDELOLW\ 5HSRUW DQG 3ODQ ëííí 3XEOLVKHG IRU WKH 3RULUXD .DSLWL +HDOWKOLQNV 3URMHFW E\ WKH 0LQLVWU\ RI +HDOWK 32 %R[ èíìêñ :HOOLQJWRQñ 1HZ =HDODQG $XJXVW ëííí ,6%1 íðéæåðëêäåìðè õ%RRNô ,6%1 íðéæåðëêäåéð; õ:HEô 7KLV GRFXPHQW LV DYDLODEOH RQ WKH ZHE VLWHVã KWWSãîîZZZïPRKïJRYWïQ] KWWSãîZZZïSFFïJRYWïQ] &RYHU SKRWR XVHG ZLWK WKH SHUPLVVLRQ RI WKH 3RULUXD &LW\ &RXQFLOï &RQWHQWV ([HFXWLYH 6XPPDU\ [L ,QWURGXFWLRQ ì 6HFWLRQ ìã +HDOWK 6HFWRU &RQWH[W é 6HFWLRQ ëã 3RULUXD &LW\ ìí 6HFWLRQ êã +HDOWK DQG 'LVDELOLW\ 6WDWXV RI 3RULUXD 3HRSOH ìä +HDOWK ULVN IDFWRUV ìä 0RUWDOLW\ ëë 0RUELGLW\ ëê 0lRUL KHDOWK VWDWXV LQ 3RULUXD ëé 3DFLILF SHRSOHV© KHDOWK VWDWXV LQ 3RULUXD ëç 6HFWLRQ éã +HDOWK DQG 'LVDELOLW\ 6HUYLFHV IRU 3HRSOH LQ 3RULUXD ëä 3XEOLF KHDOWK ëä 3ULPDU\ FDUH êì 0lRUL KHDOWK êè 3DFLILF SHRSOHV© KHDOWK êæ 0DWHUQLW\ VHUYLFHV êä &KLOG DQG \RXWK KHDOWK éë 2OGHU SHRSOH©V KHDOWK éè 'HQWDO KHDOWK éå /DERUDWRU\ñ ;ðUD\ñ SKDUPDFHXWLFDO DQG VXSSRUW VHUYLFHV èí 6SHFLDOLVW PHGLFDO DQG VXUJLFDO VHUYLFHV èé 'LVDELOLW\ VXSSRUW VHUYLFHV çí 0HQWDO KHDOWK VHUYLFHV çé 6HFWLRQ èã 5HFRPPHQGDWLRQV çæ ,QWHUVHFWRUDO DFWLRQ RQ KHDOWK çå ,PSURYHG HTXLW\ DQG IDLUQHVV æí *UHDWHU DFFHSWDELOLW\ RI VHUYLFHV æé %HWWHU DFFHVV WR VHUYLFHV ææ %HWWHU LQWHJUDWLRQ RI VHUYLFHV åè $SSHQGLFHV $SSHQGL[ ìã 0HWKRGRORJ\ åä $SSHQGL[ ëã 3RULUXD &LW\ äì $SSHQGL[ êã 2UJDQLVDWLRQV LQ 3RULUXD ìíå $SSHQGL[ éã +HDOWK 5LVN )DFWRUV ììí $SSHQGL[ èã 0RUWDOLW\ ììè $SSHQGL[ çã $YRLGDEOH 0RUELGLW\ ììä $SSHQGL[ æã 3XEOLF +HDOWK ìëë &217(176 ,,, $SSHQGL[ åã 3ULPDU\ &DUH ìëè $SSHQGL[