Caring Deception : Community Art in the Suburbs of Aotearoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

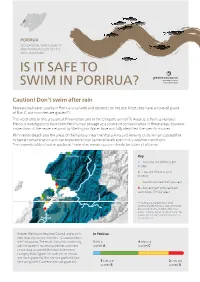

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site. -

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

Is it safe to swim in Porirua? Greater Wellington Regional Council and local councils monitor some of the Wellington region’s most popular beaches and rivers to determine their suitability for recreational activities such as swimming. We monitor eleven coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring are compared to national guidelines and used to calculate an overall grade for each site. Results from the 2014/15 summer season Recreational water quality in Porirua is quite variable with most sites having an overall grade of ‘C’. The best sites are at Karehana and Onehunga bays. These sites have an overall grade of ‘B’ and the Karehana Bay site met the guideline for safe swimming on all occasions. The worst sites were at the southern ends of Plimmerton Beach and Titahi Bay, and Te Awarua o Porirua Harbour at the Rowing Club. These sites recorded high bacterial counts on one occasion during the 2014/15 summer and have an overall grade of ‘D’. Very low risk of illness 0% Low risk 18% (2 sites) B Moderate risk 55% C (6 sites) Caution 27% (3 sites) D Unsuitable for swimming 0% In the Porirua area, 2 sites (18%) are graded ‘B’, 6 sites (55%) are graded ‘C’ and 3 sites (27%) are graded ‘D’. WAIT TWO DAYS AFTER RAIN before you swim again… Water quality at Porirua beaches is at its worst after heavy rain. Rain flushes contaminants from urban and rural land into water and we advise people not to swim for two days after heavy rain – even if a site generally has good water quality. -

Porirua – Our Place, Our Future, Our Challenge Let's Kōrero

COPYRIGHT © You are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to Porirua City Council. Published March 2021. Porirua City Council 16 Cobham Court PO Box 50218 Porirua 5240 This document is available on our website poriruacity.govt.nz Porirua – our place, our future, our challenge Let’s kōrero Consultation Document for the proposed Long-term Plan 2021-51 Message from Ngāti Toa Rangatira E te iwi e noho nei i te riu o Porirua, tēnā koutou katoa The development of the city's Long-term Plan 2021-2051 will bring changes to our city that we will be proud of. Between now and 2051 we will see Porirua transform into a vibrant and exciting place to be for residents and people who choose to work here. We are blessed with hills, waterways, Te Mana o Kupe bushwalks and two magnificent harbours, Porirua and Pāuatahanui, as well as rich histories all anchored by Te Matahourua, the anchor left here by Kupe. As a challenge to all of us – we must look after our environment and look after each other, especially our tamariki and rangatahi. Nou te rourou, naku te rourou ka ora ai te Iwi With your contribution, and my contribution the people will thrive Taku Parai Chairman, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Toa Rangatira 2 Consultation Document for the proposed LTP 2021-51 Contents Mai i tō Koutou Koromatua 4 From your Mayor Executive summary 8 Rates 10 The challenges for our city 11 Your views 16 Investment in the 3 waters – drinking water, wastewater 17 & stormwater 1. -

Your Guide to Summer 2019-20 Rangituhi Summit Photo: Jay French Walk and Walk Bike Bike Porirua Dogs Allowed

Discover Porirua Your guide to summer 2019-20 Rangituhi Summit Photo: Jay French Walk and Walk Bike bike Porirua Dogs allowed Celebrate the long, sunny days of summer with Ara Harakeke Titahi Bay Beach and a wide range of outdoor adventures in our 9.1km, 2 hr 30 min (one way) Southern Clifftop own big, beautiful backyard. We have lots of This track takes you through Mana, 2.8km, 1 hr (return) biking and hiking options to help you explore Plimmerton, and Pukerua Bay and If you’re after a mesmerising coastal includes four beaches, a wetland, view, this is the trail for you. Start Porirua’s great outdoors – from tamariki-friendly a steam train operation and historic at the south end of Titahi Bay strolls to challenging tracks for even the most World War II sites. The flat and Beach and then join the Southern easy track makes it particularly Clifftop Walk to enjoy views to seasoned and fearless mountain biker. popular for biking with tamariki. Mana Island and beyond. Te Ara Utiwai, Escarpment Track Te Ara Piko Whitireia Park Rangituhi 10km, 3-5 hr (one way) 3.2km, 50 min (one way) 6.5km, 1 hr 50 min (one way) 6.1km, 1 hr 45 min (one way) Stretching from Pukerua Bay to Take in the serene coastal wetland There are few tracks in New Zealand There are a range of tracks on Paekākāriki, this track will give atmosphere and the gorgeous inlet that can match the dramatic views the beautiful hills to the west of you bragging rights that you’ve views when you take the popular that Whitireia Park offers. -

Regional Community Profile

Regional community profile: Wellington Community Trust October 2020 Contents 1. Summary of Findings 3 2. Background 5 2.1 Indicator data 6 2.2 Interpreting the indicator data tables in this report 7 3. Indicator Data 8 3.1 Population 8 3.2 Socio-economic deprivation 13 3.3 Employment and income 16 3.4 Education 17 3.5 Housing 19 3.6 Children and young people 21 3.7 Community wellbeing 23 3.8 Environment 25 References 26 Centre for Social Impact | Wellington Community Trust – Community Profile September 2020 | Page 2 1. Summary of Findings Population and projections (2018 Census) ● Population: The WCT region is home to around 469,047 people, or 9.8% of New Zealand’s population. It has five territorial authority areas. Two thirds of the people in the WCT region reside in two of these five areas – Wellington City (45%) and Lower Hutt City (22%). Porirua has 12% of the WCT population, followed by 11% in Kapiti Coast District and 9% in Upper Hutt City. ● Population projection: The WCT region’s population will increase by 11% by 2038. Projected population growth in the region is lower than the projected New Zealand average (20%). This means that by 2038, the WCT region is projected to represent a slightly reduced 9.0% of New Zealand’s population. ● Ethnicity: Porirua (22%) and Lower Hutt (10%) have populations with the highest proportion of Pacific Peoples in the WCT region. Both areas also have the populations with the highest proportion of Māori (18% and 16% respectively). Population projections show that Māori and Pacific communities will grow further in proportion in these two areas by 2038. -

Titahi Bay Porirua East HIGH FREQUENCY & STANDARD ROUTES

Effective from 31 March 2019 Titahi Bay Porirua East HIGH FREQUENCY & STANDARD ROUTES 220 210 226 Titahi Bay Porirua Cannons Creek Thanks for travelling with Metlink. Waitangirua Connect with Metlink for timetables Ascot Park and information about bus, train and ferry services in the Wellington region. metlink.org.nz 0800 801 700 [email protected] Printed with mineral-oil-free, soy-based vegetable inks on paper produced using Forestry Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified mixed-source pulp that complies with environmentally responsible practices and principles. Please recycle and reuse if possible. Before taking a printed timetable, check our timetables online or use the Metlink commuter app. GW/PT-G-19/16 March 2019 March GW/PT-G-19/16 D ev iat ion Rocky Bay M Porirua Harbour a n a TITAHI BAY/PORIRUA EAST (Pauatahanui Arm) E s p l a n a d e RICHARD ST Thornley Street t Ba e Ivey Bay y e D r r t S k c O Titahi Bay a o t k e m e i tr S A tt D lle v i e d J Browns Bay Bradleys Roa n emata u Par e Bay TE PENE AVE PAUATAHANUI d ce a erra o osun T R PAREMATA B ti K re a i h e T u v R i r o a D d d d r e TITAHI BAY Te Onepoto Bay a iv a r o D R w ks a e e an v e e g i B L v r i h n r p S e a D D os a J h Tirau e r m t w t e e G o a k Ayton Drive w re aC r t l r i g a r e S o ro t Bay a T n r a B s l TITAHI BAY – u l n K m o i D i P p n r S i 210 g v PIKARERE ST s Dr e H e iv e e h i it N u ll ta n S o e e r WHITBY v eStree t i t v r Puk h e A D T k e o n TITAHI BAY – o e C y e P v i PAPAKOWHAI a s r D e e 220 w n T GLOAMING HILL o n m ti -

Nohorua Kotua

In the Waitangi Tribunal Wai 207 Wai 785 Under the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 In the Matter of the Northern South Island Inquiry (Wai 785) And In the Matter of a claim to the Waitangi Tribunal by Akuhata Wineera, Pirihira Hammond, Ariana Rene, Ruta Rene, Matuaiwi Solomon, Ramari Wineera, Hautonga te Hiko Love, Wikitoria Whatu, Ringi Horomona, Harata Solomon, Rangi Wereta, Tiratu Williams, Ruihi Horomona and Manu Katene for and on behalf of themselves and all descendants of the iwi and hapu of Ngati Toa Rangatira BRIEF OF EVIDENCE OF NOHORUA AKUHATA TE KOTUA Dated 9 June 2003 89 The Terrace PO Box 10246 DX SP26517 Wellington Telephone (04) 472 7877 Facsimile (04) 472 2291 Solicitor Acting: D A Edmunds Counsel: K Bellingham/K E Mitchell/B E Ross 031600121 jmc BRIEF OF EVIDENCE OF NOHORUA AHUKATA TE KOTUA Introduction 1 My name is Nohorua Akuhata Te Kotua. I was born in Nelson, on 11 June 1941. I live at 116a Kawai Street Nelson. I have lived in Nelson for most of my life apart from an eight year period serving with the New Zealand Army in New Zealand and overseas on Active Service . 2 I am Ngati Toa from my father Nohorua Akuhata Te Kotua and his father Pehiatea Akuhata Te Kotua. Through them I am descended from Nohorua, the Tohunga Rangatira of Ngati Toa and brother of Te Rauparaha. 3 I am Ngati Koata from my Mother Wetekia Elva Kawharu. Her father was Te Hahi Ngamuka Kawharu, and his father was Ngamuka Kawharu, his mother was Tiripa Tawhe Te Ruruku Kawharu. -

Key Issues Report Notice of Requirement and Resource

Key Issues Report Notice of Requirement and Resource Consent applications for the Transmission Gully Project New Zealand Transport Authority, Porirua City Council, and Transpower NZ Limited Greater Wellington Regional Council Commissioned by the Environmental Protection Authority under Section 149G(3) of the Resource Management Act 6 September 2011 Report Author Date Tracey Grant Team Leader Contributor Date Richard Percy Senior Resource Advisor Peer Reviewer Date Alistair Cross Manager, Environment Regulation Contents 1. Purpose 1 2. Terms 1 3. Scope 1 4. Relevant plan provisions 2 5. Summary of Consents 15 6. Activity status of all proposed activities 17 7. Confirmation of the status and weighting of any relevant regional policy statement, and or relevant plan 17 8. Permitted baseline 18 9. Any other key issues 21 Appendices Appendix A - Plan Change – Draft Decision wording of Policies Appendix B – National Environmental Standards Appendix C - Permitted activities – Wellington Regional Council Plans Appendix D – Active resource consents Appendix E – Approximate location of resource consents Appendix F - Pending resource consents 1 PURPOSE 1.1 To prepare a report pursuant to section 149G(3) of the Resource Management Act 1991 (the Act) to contextualise the Transmission Gully proposal (TGP) within GW‘s planning framework and instruments and to identify any key issues. 2 TERMS Act Resource Management Act 1991 EPA Environmental Protection Authority GW Greater Wellington Regional Council KCDC Kapiti Coast District Council NES-AQ National -

THE ·Ww , ZEALAND GAZETTE Fno. 98

J1umb. 98 1297 , 1 THE (~~:·\·[. NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE :EXTRAORDINARY iuhlisyth by :!\utgoritn WELLINGTON, WEDNESDAY~ NOVEMBER 10, 1943 Notice as to Men caUed up unef,er the _National S,ervi,c.e Emergency Regulations 1940 for Service with the Armed. Forces URSUA_ N_ T to the provisions ,of Regulation_ 16_- of th_ e National Service Emergency Regulations 1940, I, P Angus McLagan, Minister of National Service, do hereby give notice that the names of the men whose residential addresses and occupations are set forth in the Schedule hereto, comprising all the men whose names appear in the Register of Classes S. 18-19, S. 20, and S. 21-40 of the the First Division of the General Re~erve, and in the Register of Classes M. 18-19, M. 20, M. 21-40, and Classes C. 18 to C. 40 (both inclusive) of the Second Division of the General Reserve, have b~en certified to me in accordance with __ Regulation 15 and in compliance with a Warrant issued .under· my hand authorizing and requiring the Director to call up from the classes above mentioned the number of men specified in such Warrant for service with the Armed ·Forces: And I do b.ereby declare pursuant to Regulation 16 aforesaid that such men are c~lled up for service with the Armed Forces accordingly. A. McLAGAN, - Dated this 10th ·day of November, 1943. Minister of National Service. SCHEDULE N OTE.-This notice includes 1~he names of a number of men who have volunteered ·for overseas service and also includes the names of some men who are already serving in Home Defence Units MILITARY· AREA No. -

Paleotsunami Investigations Okoropunga and Pukerua Bay

GeoEnvironmental Consultants Paleotsunami investigations Okoropunga and Pukerua Bay Prepared for Wellington Regional Council 0 L1 $ caring about you your environment Paleotsunami investigations — Okoropunga and Pukerua Bay GeoEnvironmental Consultants In Association with Bruce McFadgen (ArchResearch) Prepared for Wellington Regional Council Information contained in this report should not be used without the prior consent of Wellington Regional Council. This report has been prepared by GeoEnvironmental Consultants exclusively for and under contract to the Wellington Regional Council. Unless otherwise agreed in writing, all liability of the consultancy to any party other than Wellington Regional Council in respect of this report is expressly excluded. Approved by: James Goff, PhD GeoEnvironmental Client report: GE02002/20022/6 June 2002 GeoEnvironmental Consultants 11 The Terrace, Governors Bay, Lyttelton RD1, New Zealand Tel: +64 3 329 9533; Fax: +64 3 329 9534; e-mail: [email protected] Paleotsunami investigations — Okoropunga and Pukerua Bay EXECUTIVE SUM Possible paleotsunami sites were investigated in the Okoropunga and Pukerua Bay areas. A late 15th Century tsunami deposit is reported from Okoropunga, and its association with an overlying gravel soil is discussed. The argument for this being a tsunami as opposed to a storm deposit is addressed with use being made of the ,-.rd i April 2002 storm deposit that was laid down in the area. Material was also taken from a site at Te Oroi, where it was noted that recent storm activity had exposed a considerable length of coastal sediments, providing a rare opportunity for future work. The tsunami deposit is linked with other evidence from around the region and elsewhere. -

Porirua City Council

Porirua City Council No STREET City HAIL CLASSIFICATION CONTAMINANTS 218 CHAMPION ST CANNONS CREEK Service Stations Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 5 MUNGAVIN AVE CANNONS CREEK Service Stations Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 12 MUNGAVIN AVE CANNONS CREEK Storage Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 100 -106 MUNGAVIN AVE CANNONS CREEK Landfill, Landfill Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry RIBBONWOOD TCE CANNONS CREEK Landfill Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry DISCOVERY DR HOROKIRI Waste Storage/Treatment/Disposal Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 102 FLIGHTYS RD HOROKIRI Livestock Dip or Spray Race Operations Unverified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry GRAYS RD HOROKIRI Defence Works Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 339 GRAYS RD HOROKIRI Defence Works Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry GRAYS RD HOROKIRI Defence Works Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 564 HAYWARDS RD HOROKIRI Landfill Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry HILLSIDE RD HOROKIRI Livestock Dip or Spray Race Operations Unverified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 1007 MOONSHINE RD HOROKIRI Livestock Dip or Spray Race Operations Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 0 0E6 MOONSHINE RD HOROKIRI Service Stations, Timber Treatment Verified History of Hazardous Activity or Industry 0 4E7 MOONSHINE RD HOROKIRI Livestock Dip or Spray Race Operations Verified History of Hazardous Activity or -

Pā in Porirua

Tuhinga 26: 1–19 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2015) Pä in Porirua: social settlements Pat Stodart Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: This paper examines the records of 12 pä (fortified settlements) and käinga (settlements) in use during the Ngäti Toa occupation of Porirua in the 1823–52 period. The histories of each pä and of their major builders are briefly recorded, focusing on the reasons for both the founding and the abandonment of the pä. This information is examined and the conclusion drawn that the creation of these pä was primarily the result of social dynamics. Environmental resources seem to affect the siting of these pä rather than causing their creation. This interpretation may shed some light on why so many pä were built throughout the later part of New Zealand prehistory and the European contact period. KEYWORDS: Pä, käinga, settlement pattern, Porirua, New Zealand, Ngäti Toa. Introduction Is it a pä? A note on The construction of a new pä or large käinga is a monu - nomenclature mental undertaking in the true sense of the word. It was not The term pä is used in this paper. Historically it was often carried out lightly, nor was it carried out for a single reason. used interchangeably with the term käinga. This is because At least two deliberate decisions need to be made before a in some instances it is difficult to determine if the defence of new pä is made: first to create a new pä; and second, where a settlement was considered a defining point from the to site it.