A Socio-Demographic Snapshot of Porirua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Overview

Air, land and water in the Wellington region – state and trends Regional overview This summary highlights the key findings from State of the Environment monitoring we carry out of natural resources across the Wellington region. It is drawn from eight technical reports which give the full picture of the health of the Wellington region’s air, land, fresh waters and coast. The reports, published every five years, are based on environmental monitoring and investigations over the past five to ten years (and longer for some resources). The findings are informing the current review of Greater Wellington’s regional plans – the ‘rule books’ for ensuring our region’s natural resources are sustainably managed. These plans are now more than ten years old and we are developing a new integrated plan. Community input to the review is critical – you can find out how to have a say on the back page. How do we measure the health of the region’s air, land and water resources? Regional councils have a legal responsibility under section 35 of the Resource Management Act 1991 to monitor the state of the environment – this essentially means tracking the quality and quantity of the region’s natural resources over time. Greater Wellington does this through long-term monitoring programmes across the region focusing on: ● Air quality at 6 locations ● Soil quality (118 sites under a range of different land uses) and stability ● Rainfall (at 50 sites) and river flows/levels (at 45 sites) ● Groundwater levels (at 146 sites) and quality (at 71 sites) ● Water quality at popular river and beach recreation spots (100 sites) ● River/stream water quality and ecosystem health (at 55 sites) ● The health of selected estuaries and our two harbours Measuring river flow We also carry out short-term investigations where our routine monitoring identifies gaps or potential problems, such as poor air or water quality. -

Foton International

Date: 23/06/2020 To: Service Managers, Parts Managers, Warranty Administrators From: Foton International Subject: FOTON PASSENGER VEHICLE (PV): NEW ZEALAND SERVICE AGENTS Model: Passenger Vehicles (Tunland, Sauvana & View) Bulletin type: AFTERSALES Reference: FDBA-LW23062020 Foton International Foton Passenger Vehicle (PV) Service Agents: Tunland, View & Sauvana Genuine Foton: Parts, Service & Warranty Location WHANGAREI Dealer Name Northland Autos Phone 09 438 7043 54 Port Road Workshop Address Morningside Whangarei 0110 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Home Tune NZ Phone T: 09 630 3000 26 Botha Road Workshop Address Penrose Auckland 1060 Location AUCKLAND Dealer Name Enterprise Manukau Phone 021 292 3546 567 Great South Road Workshop Address Manukau Auckland 2025 Location HAMILTON Dealer Name Ebbett Waikato Ltd Phone 07 838 0949 204-208 Anglesea Street Workshop Address Hamilton 3204 Location TAURANGA Dealer Name Ebbett Tauranga Phone 07 578 2843 123 Cameron Road Workshop Address Tauranga 3140 1 Location ROTORUA Dealer Name Grant Johnstone Motors Phone 07 349 2221 24-26 Fairy Springs Road Workshop Address Fairy Springs Rotorua 2104 Location TAUPO Dealer Name Central Motor Hub Phone 022 046 5269 79 Miro Street Workshop Address Tauhara Taupo 3330 Location GISBORNE Dealer Name Enterprise Motors Phone 06 867 8368 323 Gladstone Rd Workshop Address Gisborne 4010 Location HASTINGS Dealer Name The Car Company Phone 06 870 9951 909 Karamu Road North Workshop Address Hastings 4122 Location NEW PLYMOUTH Dealer Name Ross Graham Motors Ltd Phone 06 -

Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/9

Wriggle coastalmanagement Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council June 2009 Porirua Harbour Intertidal Fine Scale Monitoring 2008/09 Prepared for Greater Wellington Regional Council By Barry Robertson and Leigh Stevens Cover Photo: Upper Pauatahanui Arm of Porirua Harbour from mouth of Pautahanui Stream. Wriggle Limited, PO Box 1622, Nelson 7040, Ph 0275 417 935, 021 417 936, www.wriggle.co.nz Wriggle coastalmanagement iii Contents Porirua Harbour 2009 - Executive Summary . vii 1. Introduction . 1 2. Methods . 4 3. Results and Discussion . 8 4. Conclusions . 15 5. Monitoring ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 6. Management ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 8. References ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 Appendix 1. Details on Analytical Methods �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Appendix 2. 2009 Detailed Results . 17 Appendix 3. Infauna Characteristics . 23 List of Figures Figure 1. Location of sedimentation and fine scale monitoring -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

REFEREES the Following Are Amongst Those Who Have Acted As Referees During the Production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science

105 REFEREES The following are amongst those who have acted as referees during the production of Volumes 1 to 25 of the New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science. Unfortunately, there are no records listing those who assisted with the first few volumes. Aber, J. (University of Wisconsin, Madison) AboEl-Nil, M. (King Feisal University, Saudi Arabia) Adams, J.A. (Lincoln University, Canterbury) Adams, M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Agren, G. (Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala) Aitken-Christie, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Allbrook, R. (University of Waikato, Hamilton) Allen, J.D. (University of Canterbury, Christchurch) Allen, R. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Allison, B.J. (Tokoroa) Allison, R.W. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Alma, P.J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Amerson, H.V. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh) Anderson, J.A. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Andrew, LA. (Telstra, Brisbane) Armitage, I. (NZ Forest Service) Attiwill, P.M. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Bachelor, C.L. (NZ FRI, Christchurch) Bacon, G. (Queensland Dept of Forestry, Brisbane) Bagnall, R. (NZ Forest Service, Nelson) Bain, J. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baker, T.G. (University of Melbourne, Victoria) Ball, P.R. (Palmerston North) Ballard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bannister, M.H. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Baradat, Ph. (Bordeaux) Barr, C. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bartram, D, (Ministry of Forestry, Kaikohe) Bassett, C. (Ngaio, Wellington) Bassett, C. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (Ministry of Forestry, Rotorua) Bathgate, J.L. (NZ Forest Service, Wellington) Baxter, R. (Sittingbourne Research Centre, Kent) Beath, T. (ANM Ltd, Tumut) Beauregard, R. (NZ FRI, Rotorua) New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1): 105-119 (1998) 106 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 28(1) Beekhuis, J. -

International Student Directory

International Student Directory Giving links to various community groups and support organisations in the greater Wellington Region please visit: multiculturalnz.org.nz 1 Tertiary Providers (Universities and Technical Institutes) generally have significant support services and resources available within their own organisation. These services are specific to the institution and only available to students enrolled at that institution. However, some Tertiary information published is generic and may be helpful to the greater Providers international student community. NZQA Approved Wellington Tertiary Providers Provider Name Type Address Email Website Elite Management PTE Levels 3,4 & 6 [email protected] www.ems.ac.nz School Grand Central Tower 76 - 86 Manners St Wellington NZ Institute PTE NZIS Stadium Centre wellington@nzis. www.nzis.ac.nz of Sport Westpac Stadium ac.nz 105 Waterloo Quay Wellington NZ School of PTE Level 10, 57 Willis St [email protected] www.acupuncture. Acupuncture Wellington ac.nz and TCM NZ School PTE Te Whaea: dance@ www. of Dance National Dance and nzschoolofdance. nzschoolofdance. Drama Centre ac.nz ac.nz 11 Hutchison Rd Newtown, Wellington Te Kura Toi PTE Te Whaea: drama@toiwhakaari. www.toiwhakaari. Whakaari o National Dance and ac.nz ac.nz Aotearoa: Drama Centre NZ Drama School 11 Hutchison Rd Newtown, Wellington Te Rito Maioha: PTE Ground Floor studentservices@ www.ecnz.ac.nz Early Childhood 191 Thorndon Quay ecnz.ac.nz NZ Inc. Wellington The Learning PTE 182 Eastern Hutt Rd [email protected] www.tlc.ac.nz Connexion Ltd Taita, Lower Hutt 2 Provider Name Type Address Email Website The Salvation PTE 20 William Booth michelle_collins@ www.salvationarmy. -

Caring Deception : Community Art in the Suburbs of Aotearoa

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Caring Deception: Community art in the suburbs of Aotearoa (New Zealand) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts at Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand. By Tim Barlow 2016 2 Abstract In Aotearoa (New Zealand), community art practice has a disadvantaged status and a poorly documented national history. This thesis reinvigorates the theory and practice of community art and cultural democracy using adaptable and context-specific analyses of the ways that aesthetics and ethics can usefully co-exist in practices of social change. The community art projects in this thesis were based in four suburbs lying on the economic and spatial fringes of Aotearoa. Over 4 years, I generated a comparative and iterative methodology challenging major binaries of the field, including: ameliorative vs. disruptive; coloniser vs. colonised; instrumental vs. instrumentalised; and long term vs. short term. This thesis asserts that these binaries create a series of impasses that drive the practice towards two new artistic categories, which I define as caring deception and the facade. All the projects I undertook were situated in contested space, where artists working with communities overlapped with local and national governments aiming for CBD and suburban re-vitalisation, creative city style initiatives, community development, grassroots creative projects, and curated public-art festivals. -

Kapiti Coast District Council and Other Councils, Including Population Forecasts

Housing and Business Development Capacity Assessment Kāpiti Coast District Council November 2019 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment 229 230 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment Contents Executive Summary 232 5.0 Infrastructure 270 Background 233 5.1 Three Waters 270 Residential demand 233 5.2 Local Road Network 271 Residential capacity 233 5.3 State Highway Network 272 Business demand 234 5.4 Public Transport 272 Business capacity 234 5.5 Open Space 273 Infrastructure capacity 234 5.6 Education 273 1.0 Introduction 237 6.0 Relationship between Housing and Business Land 274 2.0 Existing Policy Context 238 7.0 Monitoring 275 2.1 Kāpiti Coast District Plan 238 7.1 Historic Development Activity 275 2.2 Development Management Strategy 2007 238 7.2 Market Indicators 278 2.3 Infrastructure Strategy 2018-2048 238 7.3 Price Efficiency Indicators 285 2.4 Roads of National Significance and Town Centres Transformation 239 8.0 Conclusion 293 3.0 Residential Demand and Capacity 240 9.0 Next Actions 294 3.1 Historic urban growth and settlement 240 3.2 Current growth and settlement trends 240 3.3 Future Housing Demand 241 3.4 Housing Development Capacity 248 3.5 Housing Feasibility, Realisation and Sufficiency 251 4.0 Business Demand and Capacity 258 4.1 Business Development Context 258 4.2 Current Economic and Business Drivers 259 4.3 Future Business Demand 260 4.4 Business Development Capacity 264 4.5 Business Feasibility, Realisation and Sufficiency 266 Housing and Business Land Capacity Assessment 231 Executive Summary This report presents the results from the Wellington Region Housing and Business Development Capacity Assessment (HBA) for the Kāpiti Coast District Council. -

PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1

PLIMMERTON FARM – PLAN CHANGE PROPOSAL Supporting Documentation View from Submitters Property Karla and Trevor Beamsley 24 Motuhara Road Plimmerton PLIMMERTON FARM SUBMISSION | K BEAMSLEY Page 1 1. INTRODUCTION The village of Plimmerton is a northern suburb of Porirua, and is surrounded to the North and East by farmland. It represents the edge of existing residential dwellings. Generally existing homes are stand-alone dwellings on lots greater than 500m² in size. Most residents within Plimmerton and Camborne either commute into Wellington city or work from home. The demand for housing in this area is from professional couples or families looking for 3 – 4 bedroom family homes on a section with space for kids to run around in, not medium or high density three-storey buildings and apartments, this is reflected in the TPG report to PCC (Dec 2019). Medium density style townhouses, or apartments would be totally out of character of the surrounding residential areas, and would present a stark contrast to the remaining rural areas which bound the site. The Plimmerton Farm site is not located close to areas of high employment, nor is it close to local amenities like the main shopping areas of Porirua. The site is also not located within an area currently supported by existing infrastructure. Much of the infrastructure in the area is aging, and requires repair or upgrade to support existing demands. Therefore, the idea that Plimmerton Farm would provide homes in a location close to employment, amenities and infrastructure1 is simply incorrect in terms of a 10-year time frame. Areas where this would be true include the currently developing areas of Aotea, Whitby, Kenepuru, and Porirua East. -

Te Runanga O Toa Rangatira Inc Group

Te Runanga o Toa RangaTiRa inc Group 2018 ANNUAL REPORT (1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018) Upane ka upane whiti te ra Advancing together into a brighter future Moemoea Kia tu ai a Ngāti Toa Rangatira; Hei iwi Toa, hei iwi Rangatira Ngāti Toa is a strong, vibrant and influential Iwi, firmly grounded in our cultural identity and leading change to enable whanau wellbeing and prosperity CONTENTS 2 | Contents 3 | Executives, Directors, Trustees, Committees 4 | Chairman’s Report 6 | Executive Directors Report Pitopito Korero 8 | Administration / Communication 10 | Resource Management 11 | Toa Rangatira Education Achievement Team 12 | Te Puna Reo o Ngati Toa 15 | Te Puna Matauranga 18 | Disability Service 19 | Ora Toa Mauriora 24 | Ora Toa PHO Purongo Putea 25 | Te Runanga o Toa Rangatira Incorporated Group 66 | Toa Rangatira Trust Group 92 | Ora Toa PHO 108 | Ika Toa Limited 132 | Additional Financial Information 2 | W h ā r a n g i EXECUTIVES, DIRECTORS, TRUSTEES, COMMITTEES EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: TE AWARUA O PORIRUA AUDIT, RISK & INVESTMENT Matiu Rei WHAITUA COMMITTEE: COMMITTEE: Hikitia Ropata Miria Pomare, Chair BOARD / TRUSTEES Jennie Smeaton Caroline Taurima Taku Parai Elected – Chair Sharli Jo Solomon Francis Freemantle Helmut Modlik Willis Katene Elected – Deputy Ian Lyver Arthur Selwyn Takapuwahia Marae WHAITUA TE WHANGANUI-A- Kyle Edmonds Matthew Solomon Takapuwahia Marae TARA: Patariki Hippolite Whakatu Marae Matiu Rei Miria Pomare Hongoeka Marae Taku Parai NGATI TOA / RUNANGA Moana Parata Hongoeka Marae REPRESENTATIVES: Tracey Williams -

Employment Analysis Report

Employment Analysis October 2020 Wellington Regional Growth Framework | 0 Introduction Ka ora te wai If the water is healthy Purpose of this report More detailed work, than has been undertaken in the Ka ora te whenua the land will be nourished The purpose of this report is to summarise existing Framework, will need to be undertaken to Ka ora te whenua If the land is nourished research and data to assist with regional spatial understand in more detail: Ka ora te tangata the people will be provided planning. No new analysis has been undertaken. This 1. How many jobs do we expect in each for report should be read as an input into other work, geographical area as of 2050? and not as a final conclusion on the spatial direction 2. What change is that from the current situation? for the Framework or as policy for any of the partner Mo te iti - mo te rahi For the little - for the large 3. What type of jobs are they? organisations. 4. What do we need to do to make this change? 1 As outlined in the Foundation Report for the This report builds upon the Foundation Report to Wellington Regional Growth Framework (the 2 provide background information to assist in analysing Framework), employment in the region is employment patterns and information and concentrated in central Wellington and a significant determine what changes may/could occur with number of commuters travel into central Wellington regards to employment and the Framework. from other parts of the region for employment. A key direction during development of the Regional employment is dominated by knowledge- Framework with regards to employment has been to based sector employment. -

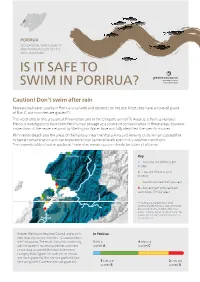

Is It Safe to Swim in Porirua?

PORIRUA RECREATIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING RESULTS FOR THE 2017/18 SUMMER IS IT SAFE TO SWIM IN PORIRUA? Caution! Don’t swim after rain Recreational water quality in Porirua is variable and depends on the site. Most sites have an overall grade of B or C, but two sites are graded D. The worst sites in this area are at Plimmerton and in the Onepoto arm of Te Awarua-o-Porirua Harbour. Previous investigations have identified human sewage as a source of contamination in these areas, however inspections of the sewer network by Wellington Water have not fully identified the specific sources. Plimmerton Beach and the areas of the harbour near the Waka Ama and Rowing clubs remain susceptible to faecal contamination and can experience high bacterial levels even in dry weather conditions. The unpredictably of water quality at these sites means caution should be taken at all times. Pukerua Bay Key A – Very low risk of illness 8% (1 site) B – Low risk of illness 42% (5 sites) Plimmerton C – Caution advised 33% (4 sites) D – Sometimes* unsuitable for swimming 17% (2 sites) Te Awarua o Porirua Titahi Bay Harbour Whitby *Sites that are graded D tend to be significantly affected by rainfall and should be avoided for at least 48hrs after it has rained. However water quality at these sites may be safe for swimming for much of the Porirua rest of the time. Tawa Greater Wellington Regional Council, along with In Porirua: your local city council, monitors 12 coastal sites in the Porirua area. The results from this monitoring 1 site is 4 sites are are compared to national guidelines and used graded A graded C to calculate an overall Microbial Assessment Category (MAC) grade for each site.