Developing Students' Global Competence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Exchanges

Student Exchanges Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Rationale ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 How Do Students Qualify and Apply ........................................................................................................................... 3 Student Profile Sheet .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Section A .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Section B .................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Rules for Exchanges ................................................................................................................................................... 10 Information for Outgoing Exchange Students ............................................................................................................ 16 Academic Issues ......................................................................................................................................................... 17 Exchange -

NEW BUYERS GUIDE-3.Indd

Information Guide 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Core Values Secure Living Spacious Country Living Socio-environmental ethos Social well-being Sustainable Financial Return 2. Val de Vie Estate Milestones 3. Val de Vie Estate Property Sales 4. Val de Vie Estate Products RANKED THE MOST OUTSTANDING MULTIGENERATIONAL RESORT 5. Phase 2 Amenities and Facilities IN THE WORLD IN 2018 BY GLOBAL OVER 50S 6. Development Company Management HOUSING/HEALTHCARE AWARDS 2018 7. Val de Vie Estate Location and Demographics 8. Advice for Potential Buyers 9. Cost of Living 10. Val de Vie Property Finance 11. Foreign Buyers 12. References TOP 5 GOLF COURSE IN SOUTH AFRICA FOR 2018 & 2019 BY GOLF DIGEST MAGAZINE THE ESTATE CORE VALUES • Safety and security • Wellness orientated • Hospitality • Spacious country living • Green environmental practices, indigenous rehabilitation and conservation • Social responsibility • Sustainable agricultural development • Financial return and growth • Cutting edge technology and techniques SECURE LIVING • A profound understanding that safety and security is vital to all residents • One of the first estates in South Africa to implement biometric-access control measures, allowing for tracking of entrance and exit and movement of persons through the different areas of the estate • Technologically advanced security measures • Regular and unplanned security stress testing • 15.5 km’s of physical barriers consisting of a 2-kilometres-high wrought-iron fence, concrete plinths, full electrified fence and anti-dig razor wire • 112 thermal -

THE ATHENIAN SCHOOL Dean of Experiential Education

THE ATHENIAN SCHOOL Dean of Experiential Education SUMMARY Location | Danville, CA Post Date | January 7, 2021 Application Deadline | February 5, 2021 at 5:00pm PST Semifinal Round | Week of February 16 Final Round | Week of March 1 Decision Announced | March 19, 2021 Start Date | July 1, 2021 Reports To | Assistant Head of School The Athenian School | Dean of Experiential Education SUMMARY Internationalism. Democracy. Environmentalism. Adventure. Leadership. Service. These are the pillars of Round Square, an international network of 200+ schools in 50+ countries that The Athenian School co-founded. Athenian, a grades 6-12 day and boarding independent school located on 75 acres near the rolling East Bay hills of the San Francisco Bay Area, has been living out its mission of experiential learning as a Round Square school since 1966. These six core values are also the pillars of a new role at Athenian: dean of experiential education. The “Pillar Dean,” as this role is affectionately known at Athenian, will be charged with coordinating several all-school experiential learning programs, but more importantly with bringing those experiential principles of learning-by-doing to the core curriculum. Thus, the dean of experiential education will serve as a critical bridge and mentor to middle and upper school faculty. The Pillar Dean, a 12-month role that reports to the assistant head of school / middle school head, starts July 1, 2021. THREE STRATEGIC PRIORITIES AT ATHENIAN 1. PROGRAM Athenian will lead the school world in creating the next generation of rigorous, project- based, experiential, and interdisciplinary curricula to deliver the knowledge and skills that students need to both succeed in an information economy and make a meaningful contribution in the world. -

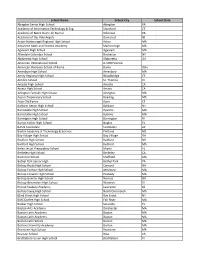

List of AOIME Institutions

List of AOIME Institutions CEEB School City State Zip Code 1001510 Calgary Olympic Math School Calgary AB T2X2E5 1001804 ICUC Academy Calgary AB T3A3W2 820138 Renert School Calgary AB T3R0K4 820225 Western Canada High School Calgary AB T2S0B5 996056 WESTMOUNT CHARTER SCHOOL CALGARY AB T2N 4Y3 820388 Old Scona Academic Edmonton AB T6E 2H5 C10384 University of Alberta Edmonton AB T6G 2R3 1001184 Vernon Barford School Edmonton AB T6J 2C1 10326 ALABAMA SCHOOL OF FINE ARTS BIRMINGHAM AL 35203-2203 10335 ALTAMONT SCHOOL BIRMINGHAM AL 35222-4445 C12963 University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingham AL 35294 10328 Hoover High School Hoover AL 35244 11697 BOB JONES HIGH SCHOOL MADISON AL 35758-8737 11701 James Clemens High School Madison AL 35756 11793 ALABAMA SCHOOL OF MATH/SCIENCE MOBILE AL 36604-2519 11896 Loveless Academic Magnet Program High School Montgomery AL 36111 11440 Indian Springs School Pelham AL 35124 996060 LOUIS PIZITZ MS VESTAVIA HILLS AL 35216 12768 VESTAVIA HILLS HS VESTAVIA HILLS AL 35216-3314 C07813 University of Arkansas - Fayetteville Fayetteville AR 72701 41148 ASMSA Hot Springs AR 71901 41422 Central High School Little Rock AR 72202 30072 BASIS Chandler Chandler AZ 85248-4598 30045 CHANDLER HIGH SCHOOL CHANDLER AZ 85225-4578 30711 ERIE SCHOOL CAMPUS CHANDLER AZ 85224-4316 30062 Hamilton High School Chandler AZ 85248 997449 GCA - Gilbert Classical Academy Gilbert AZ 85234 30157 MESQUITE HS GILBERT AZ 85233-6506 30668 Perry High School Gilbert AZ 85297 30153 Mountain Ridge High School Glendale AZ 85310 30750 BASIS Mesa -

The Appleby College Summer Eslprogram

THE APPLEBY COLLEGE SUMMER ESL PROGRAM Program for students ages 12-16 WHERE ARE WE LOCATED? Appleby College’s Summer ESL Program is located in Oakville, Ontario, Canada on the shores of Lake Ontario. We are located just 20 minutes from downtown Toronto, and 30 minutes from Toronto’s Pearson International Airport. Canada is one of the most ethnically diverse, multicultural nations on earth, and is highly ranked in government transparency, civil liberties, quality of life, economic freedom and education. 35,540,419 #1 CANADA’S POPULATION LARGEST SHARED LAND BORDER IN THE WORLD (WITH U.S.A.) 196,722 # POPULATION OF OAKVILLE, 2 ONTARIO, CANADA CANADA IS THE SECOND LARGEST COUNTRY BY TOTAL AREA > ° 30 C SUMMER HIGHS IN PARTS OF ONTARIO Appleby College, Oakville, Ontario #1 # CANADA’S RANKING 2 WORLDWIDE IN NUMBER ONTARIO IS OF ADULTS WITH POST- CANADA’S SECOND SECONDARY EDUCATION # 9,984,670 LARGEST PROVINCE 250,000 CANADA’S TOTAL AREA IN NUMBER OF FRESHWATER 2 SQUARE KILOMETRES LAKES IN ONTARIO OAKVILLE’S RANKING BEST CANADIAN MID-SIZE CITIES TO LIVE IN BY MONEYSENSE MAGAZINE 33% 1857 OF THE WORLD’S THE YEAR OAKVILLE WAS FRESHWATER IS FOUNDED BY COLONEL IN ONTARIO WILLIAM CHISHOLM WHAT SETS APPLEBY COLLEGE APART FROM THE REST? Founded in 1911, Appleby’s mission is to educate and enable young men and women to become leaders of character, major contributors to, and valued representatives of their local, national, and international communities. Appleby inspires its 750 students from grades 7 to 12 to pursue their individual passions through an internationally recognized and innovative academic, athletic, and co-curricular programme that has been founded on the school’s six Pillars of Strength: Academically Vital, Technologically Empowered, Universally Diverse, Community Spirited, Actively Engaged and Globally Responsible. -

NEW BUYERS GUIDE.Indd

Information Guide 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Core Values Secure Living Spacious Country Living Socio-environmental ethos Social well-being Sustainable Financial Return 2. Val de Vie Milestones 3. Val de Vie Property Sales 4. Val de Vie Products RANKED THE MOST OUTSTANDING MULTIGENERATIONAL RESORT 5. Phase 2 Amenities and Facilities IN THE WORLD IN 2018 BY GLOBAL OVER 50S 6. Development Company Management HOUSING/HEALTHCARE AWARDS 2018 7. Val de Vie Location and Demographics 8. Advice for Potential Buyers 9. Cost of Living 10. Val de Vie Property Finance 11. Foreign Buyers 12. References TOP 5 GOLF COURSE IN SOUTH AFRICA FOR 2018 & 2019 BY GOLF DIGEST MAGAZINE THE ESTATE CORE VALUES • Safety and security • Wellness orientated • Hospitality • Spacious country living • Green environmental practices, indigenous rehabilitation and conservation • Social responsibility • Sustainable agricultural development • Financial return and growth • Cutting edge technology and techniques SECURE LIVING • A profound understanding that safety and security is vital to all residents • One of the first estates in South Africa to implement biometric-access control measures, allowing for tracking of entrance and exit and movement of persons though the different areas of the estate • Technologically advanced security measures • Regular and unplanned security stress testing • 15.5 km’s of physical barriers consisting of a 2-kilometres-high wrought-iron fence, concrete plinths, full electrified fence and anti-dig razor wire • 112 thermal camera perimeter protection -

![[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8581/joongang-ilbo-home-a-university-campus-no-its-an-international-school-to-debut-in-incheon-258581.webp)

[Joongang Ilbo – Home&] a University Campus? No, It's an International School to Debut in Incheon

[JoongAng Ilbo – home&] A university campus? No, it’s an international school to debut in Incheon Tip: How does an international school differ from a foreign school? Chadwick International, which will open this fall, is an international school. To be more precise, it is a foreign educational institution, which differs from a foreign school. Unlike an international school, which will debut for the first time in the nation, there are some 20 foreign schools in Seoul alone. As for admission, an international school can accept local students up to 30% of its quota while a foreign school can only admit locals who have lived overseas for over three years. Also, a local school corporation is eligible to set up a foreign school while an international school is only established by a foreign education school corporation. A reporter visited Chadwick International, with a couple of experts specializing school architecture. A prestigious foreign private institution has finally arrived in Korea. And that is Chadwick International in Songdo International City that has been established, in accordance with “The Special Laws on Establishment and Operations of Foreign Educational Institution.” Its annual tuition fees reach more than KRW 30 million, and its unique building structure and design seems to be a grand preview of what to be offered. “The school has been designed to facilitate our primary education goal through the state-of-art facility features and carefully- customized classrooms for kids,” R. Warmington, President and CEO of Chadwick International, said. Most prestigious private education institutions stress that education starts from the very stage, at which a school building is designed, not from the school curriculum. -

The Armidalian

The Armidalian 2019 The Armidalian is the magazine of record of The Armidale School, Armidale NSW Australia. Credits Editor: Tim Hughes Design & Layout: Donna Jackson Cover Photo: Tim Hughes, Year 12 Final Assembly The Armidalian Volume 121 2019 Contents Introduction 2 Year 12 Awards 42 Middle School 92 Staff 4 Valedictory Day Address 44 Head of Middle School 94 Vale Murray Guest 6 Valedictory Day Responses 47 Junior School 98 Redress and Reflection 12 Valete 50 Head of Junior School 100 Chairman’s Address 14 SRC and House Captains 71 Junior School Sport 103 Acting Headmaster’s Address 16 Salvete and Valete 72 Junior School Speech Day Awards 106 Speech Day Guest 19 Junior School Photo 108 Senior Prefects’ Addresses 21 Academic Reports 74 Transition 110 Chaplain’s Report 24 Academic Extension 76 Kindergarten 111 Wellbeing and Pastoral Care 26 Agriculture 78 Year 1 112 Counsellor’s Report 28 Creative Arts 79 Year 2 113 Aboriginal Students’ Program 29 English 80 Year 3 114 Comings and Goings 30 HSIE 82 Year 4 115 Descendants of Old Armidalians 31 Languages 83 Year 5 116 Director of Boarding 32 Mathematics 85 PDHPE 86 Leadership, Service & Adventure 118 Senior School 34 Science 87 Round Square 120 Director of Studies’ Report 36 TAS 89 Cadets 124 Speech Day Prizes 38 ANZAC Address 128 Prefects & House Captains 41 The Armidalian Passing Out Parade 130 Croft 154 Mountain Biking 194 Bush Skills 132 Girls’ Boarding 156 Netball 196 Rangers 133 Green 158 Rowing 198 Rural Fire Service 134 Ross 159 Rugby 200 Surf Lifesaving 135 Tyrrell 160 TAS Rugby -

Participating School List 2018-2019

School Name School City School State Abington Senior High School Abington PA Academy of Information Technology & Eng. Stamford CT Academy of Notre Dame de Namur Villanova PA Academy of the Holy Angels Demarest NJ Acton-Boxborough Regional High School Acton MA Advanced Math and Science Academy Marlborough MA Agawam High School Agawam MA Allendale Columbia School Rochester NY Alpharetta High School Alpharetta GA American International School A-1090 Vienna American Overseas School of Rome Rome Italy Amesbury High School Amesbury MA Amity Regional High School Woodbridge CT Antilles School St. Thomas VI Arcadia High School Arcadia CA Arcata High School Arcata CA Arlington Catholic High School Arlington MA Austin Preparatory School Reading MA Avon Old Farms Avon CT Baldwin Senior High School Baldwin NY Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barnstable High School Hyannis MA Barrington High School Barrington RI Barron Collier High School Naples FL BASIS Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ Baxter Academy of Technology & Science Portland ME Bay Village High School Bay Village OH Bedford High School Bedford NH Bedford High School Bedford MA Belen Jesuit Preparatory School Miami FL Berkeley High School Berkeley CA Berkshire School Sheffield MA Bethel Park Senior High Bethel Park PA Bishop Brady High School Concord NH Bishop Feehan High School Attleboro MA Bishop Fenwick High School Peabody MA Bishop Guertin High School Nashua NH Bishop Hendricken High School Warwick RI Bishop Seabury Academy Lawrence KS Bishop Stang High School North Dartmouth MA Blind Brook High -

Choosing the Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing the Right Location

Choosing The Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing The Right Location Geography The Korean Peninsula lies in the north-eastern part of the Asian continent. It is bordered to the north by Russia and China, to the east by the East Sea and Japan, and to the west by the Yellow Sea. In addition to the mainland, South Korea comprises around 3,200 islands. At 99,313 sq km, the country is slightly larger than Austria. It has one of the highest population densities in the world, after Bangladesh and Taiwan, with more than 50% of its population living in the country’s six largest cities. Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years and you will find evidence of its rich and varied heritage in the many temples, palaces and city gates. These sit alongside contemporary architecture that reflects the growing economic importance of South Korea as an industrialised nation. In 1948, Korea divided into North Korea and South Korea. North Korea was allied to the, then, USSR and South Korea to the USA. The divide between the two countries at Panmunjom is one of the world’s most heavily fortified frontiers. Copyright © 2013 IMA Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Generated from http://www.southkorea.doingbusinessguide.co.uk/the-guide/choosing-the-right- location/ Tuesday, September 28, 2021 Choosing The Right Location Page 2 of 4 Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it is easy to see how South Korea became a world leader in shipbuilding. Climate South Korea has a temperate climate, with four distinct seasons. Spring, from late March to May, is warm, while summer, from June to early September is hot and humid. -

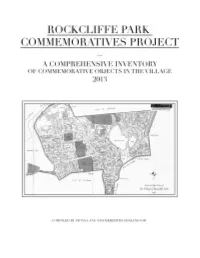

Commemoratives Project Report.Pdf

Forward' It'was'very'exciting'for'us'to'be'asked'to'create'an'inventory'of'the'historical'and' commemorative'artefacts'that'we'see'every'day'in'the'Village.'Equipped'with'Martha' Edmond’s'invaluable'Rockcliffe)Park:)A)History)of)the)Village'and'copies'of'the'Rockcliffe' Park'walking'guides'(kindly'supplied'by'Liz'Heatherington),'we'began'by'simply'walking' around'the'Village,'cameras'in'hand'and'eyes'peeled'for'anything'of'interest.'Working' from'the'Official'1993'Plan'of'the'Village,'we'divided'the'neighbourhood'between'us' and'walked'street'by'street,'crossing'off'territory'as'we'progressed.' Later,'we'arranged'visits'to'Ashbury'College,'Elmwood'School,'and'Rockcliffe'Park'Public' School,'which'allowed'us'to'photograph'the'many'fascinating'historic'objects'at'the' locations.'We'very'much'appreciate'the'help'provided'by'Vicky'Wilgress,'X,'and'X'during' this'stage.' We'photographed'benches,'Village'entrance'markers,'commemorative'plaques,'and'just' about'anything'else'we'could'find.'Then'we'used'this'photographic'record'as'the'basis' for'a'detailed'inventory.'' We'then'grouped'each'artefact'into'one'of'six'groups:'Art'U'1;'Benches'U'2;'Paths'and' Walls'U'3;'Plaques'and'Signs'U'4;'Trees'U'5;'and'a'Miscellaneous'category'U'6.'Each'object' was'given'a'four'digit'serial'code;'the'first'digit'corresponded'to'the'group'to'which'the' object'belongs.'' For'example,'a'sculpture'might'have'the'serial'number'1U002;'the'photographs'of'that' item'were'given'the'numbers'1U002U1,'1U002U2,'1U002U3,'and'so'on.' After'numbering'all'the'items'and'photos,'we'added'a'description'of'each'item'and'its' -

Teams Results

2014 Tintern Horse Trials Team Final Results Team Name Total Result Rider Horse School Avenel 0.00 117 Siobhan Minter Crystal Avenel Primary 0.00 204 Anastasia Minter Nattai Cosmos Avenel Primary 30.19 231 Monique Rouessart Indianna Seymour College 56.25 Balcombe 0.00 10 Alex Brennan Westbury Park Colorado Balcombe Grammar School 0.00 216 Dakoda Lyne My Haven Intrigue Balcombe Grammar School 34.04 217 Eliza Lloyd Tez Balcombe Grammar School 7.76 218 Jemima Quayle Rafferty Rules Balcombe Grammar School 0.00 Beaconhills 0.00 38 Isabelle Sanders Dulwich Felicia Beaconhills College 0.00 56 Jemma Turner Bits n Pieces Beaconhills College 54.93 90 Isabelle Sanders Fluent Talk Beaconhills College 83.72 Billanook 1 0.00 54 Giorgia Fontana Rangeview Falander Billanook College 41.49 76 Amelia Williams Outlaw Billanook College 0.00 169 Sophie Sampson Lad of Tintagel Billanook College 81.82 Billanook 2 157.53 17 77 Maddison Creber River Valley Cooper Billanook College 54.55 91 Giorgia Fontana Cosmic Powers Billanook College 67.92 167 Kara Willand Final Affair Billanook College 35.06 Birmingham 94.56 24 120 Kayley McKenna W P Cosmic Crusader Mt Lilydale Mercy College 73.33 210 Lilly Trevorrow Primrose Lane Birmingham Primary 13.91 213 Lily Callaway Chivas Regal St Marys Primary 0.00 239 Ella Trevorrow Risky Business Birmingham Primary 7.32 Bacchus Marsh Grammar 0.00 19 Hannah McLean Vardarrad Bacchus Marsh Grammar 66.67 50 Abby McLean Jarosite Gryffindor Bacchus Marsh Grammar 36.08 109 Mia Mclean Chester Bacchus Marsh Grammar 0.00 Brought to you by Friends of Equestrian Tintern Schools.