Mariko Okawa Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Reaction to the Sepoy Mutiny, 1857-1858 Approved

BRITISH REACTION TO THE SEPOY MUTINY, 1857-1858 APPROVED: Major /Professor mor Frotessar of History Dean' ot the GraduatGradua' e ScHooT* BRITISH REACTION TO THE SEPOY MUTINY, 1857-185S THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Samuel Shafeeq Denton, Texas August, 1970 PREFACE English and Indian historians have devoted considerable research and analysis to the genesis of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 but have ignored contemporary British reaction to it, a neglect which this study attempts to satisfy. After the initial, spontaneous, condemnation of Sepoy atrocities, Queen Victoria, her Parliament, and subjects took a more rational and constructive attitude toward the insurrection in India, which stemmed primarily from British interference in Indian religious and social customs, symbolized by the cartridge issue. Englishmen demanded reform, and Parliament-- at once anxious to please the electorate and to preserve the valuable colony of India--complied within a year, although the Commons defeated the first two Indian bills, because of the interposition of other foreign and domestic problems. But John Bright, Lord Edward Stanley, William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli, and their friends joined forces to pass the third Indian bill, which became law on August 2, 1858. For this study, the most useful primary sources are Parliamentary Debates. Journals of the House of Commons and Lords, British and Foreign State' Papers, English Historical Queen Victoria's Letters , and the Annual' Re'g'i'st'er. Of the few secondary works which focus on British reac- tion to the Sepoy Mutiny, Anthony Wood's Nineteenth Centirr/ Britain, 1815-1914 gives a good account of British politics after the Mutiny. -

Making Amusement the Vehicle of Instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900

1 ‘Making amusement the vehicle of instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900 PhD Thesis submitted by Lesley Jane Delaney UCL Department of English Literature and Language 2012 SIGNED DECLARATION 2 I, Lesley Jane Delaney confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ABSTRACT 3 ABSTRACT During the course of the nineteenth century children’s early reading experience was radically transformed; late eighteenth-century children were expected to cut their teeth on morally improving texts, while Victorian children learned to read more playfully through colourful picturebooks. This thesis explores the reasons for this paradigm change through a study of the key developments in children’s publishing from 1783 to 1900. Successively examining an amateur author, a commercial publisher, an innovative editor, and a brilliant illustrator with a strong interest in progressive theories of education, the thesis is alive to the multiplicity of influences on children’s reading over the century. Chapter One outlines the scope of the study. Chapter Two focuses on Ellenor Fenn’s graded dialogues, Cobwebs to catch flies (1783), initially marketed as part of a reading scheme, which remained in print for more than 120 years. Fenn’s highly original method of teaching reading through real stories, with its emphasis on simple words, large type, and high-quality pictures, laid the foundations for modern nursery books. Chapter Three examines John Harris, who issued a ground- breaking series of colour-illustrated rhyming stories and educational books in the 1810s, marketed as ‘Harris’s Cabinet of Amusement and Instruction’. -

Victoria: the Irg L Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R

Volume 18 Article 7 May 2019 Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Lindsay R. Richwine Gettysburg College Class of 2021 Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Richwine, Lindsay R. (2019) "Victoria: The irlG Who Would Become Queen," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 18 , Article 7. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Victoria: The irG l Who Would Become Queen Abstract This research reviews the early life of Queen Victoria and through analysis of her sequestered childhood and lack of parental figures explains her reliance later in life on mentors and advisors. Additionally, the research reviews previous biographical portrayals of the Queen and refutes the claim that she was merely a receptacle for the ideas of the men around her while still acknowledging and explaining her dependence on these advisors. Keywords Queen Victoria, England, British History, Monarchy, Early Life, Women's History This article is available in The Gettysburg Historical Journal: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol18/iss1/7 Victoria: The Girl Who Would Become Queen By Lindsay Richwine “I am very young and perhaps in many, though not in all things, inexperienced, but I am sure that very few have more real good-will and more real desire to do what is fit and right than I have.”1 –Queen Victoria, 1837 Queen Victoria was arguably the most influential person of the 19th century. -

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in the Young Victoria (2009)

Visualising Victoria: Gender, Genre and History in The Young Victoria (2009) Julia Kinzler (Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) Abstract This article explores the ambivalent re-imagination of Queen Victoria in Jean-Marc Vallée’s The Young Victoria (2009). Due to the almost obsessive current interest in Victorian sexuality and gender roles that still seem to frame contemporary debates, this article interrogates the ambiguous depiction of gender relations in this most recent portrayal of Victoria, especially as constructed through the visual imagery of actual artworks incorporated into the film. In its self-conscious (mis)representation of Victorian (royal) history, this essay argues, The Young Victoria addresses the problems and implications of discussing the film as a royal biopic within the generic conventions of heritage cinema. Keywords: biopic, film, gender, genre, iconography, neo-Victorianism, Queen Victoria, royalty, Jean-Marc Vallée. ***** In her influential monograph Victoriana, Cora Kaplan describes the huge popularity of neo-Victorian texts and the “fascination with things Victorian” as a “British postwar vogue which shows no signs of exhaustion” (Kaplan 2007: 2). Yet, from this “rich afterlife of Victorianism” cinematic representations of the eponymous monarch are strangely absent (Johnston and Waters 2008: 8). The recovery of Queen Victoria on film in John Madden’s visualisation of the delicate John-Brown-episode in the Queen’s later life in Mrs Brown (1997) coincided with the academic revival of interest in the monarch reflected by Margaret Homans and Adrienne Munich in Remaking Queen Victoria (1997). Academia and the film industry brought the Queen back to “the centre of Victorian cultures around the globe”, where Homans and Munich believe “she always was” (Homans and Munich 1997: 1). -

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries

Nielsen Collection Holdings Western Illinois University Libraries Call Number Author Title Item Enum Copy # Publisher Date of Publication BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.1 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.2 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.3 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.4 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. BS2625 .F6 1920 Acts of the Apostles / edited by F.J. Foakes v.5 1 Macmillan and Co., 1920-1933. Jackson and Kirsopp Lake. PG3356 .A55 1987 Alexander Pushkin / edited and with an 1 Chelsea House 1987. introduction by Harold Bloom. Publishers, LA227.4 .A44 1998 American academic culture in transformation : 1 Princeton University 1998, c1997. fifty years, four disciplines / edited with an Press, introduction by Thomas Bender and Carl E. Schorske ; foreword by Stephen R. Graubard. PC2689 .A45 1984 American Express international traveler's 1 Simon and Schuster, c1984. pocket French dictionary and phrase book. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 1 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. REF. PE1628 .A623 American Heritage dictionary of the English 2 Houghton Mifflin, c2000. 2000 language. DS155 .A599 1995 Anatolia : cauldron of cultures / by the editors 1 Time-Life Books, c1995. of Time-Life Books. BS440 .A54 1992 Anchor Bible dictionary / David Noel v.1 1 Doubleday, c1992. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860- 1901 Charles Vincent Reed, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Richard Price Department of History ABSTRACT: The dissertation explores the development of global identities in the nineteenth-century British Empire through one particular device of colonial rule – the royal tour. Colonial officials and administrators sought to encourage loyalty and obedience on part of Queen Victoria’s subjects around the world through imperial spectacle and personal interaction with the queen’s children and grandchildren. The royal tour, I argue, created cultural spaces that both settlers of European descent and colonial people of color used to claim the rights and responsibilities of imperial citizenship. The dissertation, then, examines how the royal tours were imagined and used by different historical actors in Britain, southern Africa, New Zealand, and South Asia. My work builds on a growing historical literature about “imperial networks” and the cultures of empire. In particular, it aims to understand the British world as a complex field of cultural encounters, exchanges, and borrowings rather than a collection of unitary paths between Great Britain and its colonies. ROYAL SUBJECTS, IMPERIAL CITIZENS: THE MAKING OF BRITISH IMPERIAL CULTURE, 1860-1901 by Charles Vincent Reed Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Advisory Committee: Professor Richard Price, Chair Professor Paul Landau Professor Dane Kennedy Professor Julie Greene Professor Ralph Bauer © Copyright by Charles Vincent Reed 2010 DEDICATION To Jude ii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS Writing a dissertation is both a profoundly collective project and an intensely individual one. -

Genevieve O'reilly

Genevieve O'Reilly Agents Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Sophie Austin Assistant [email protected] Emma Collier [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE DRY Gretchen Robert Connolly Pacific Standard TOLKIEN Mrs Smith Dome Karukoski Fox Searchlight Pictures THE SNOWMAN Birte Becker Tomas Alfredson Drapsmann Films ROGUE ONE: A STAR WARS Mon Mothma Gareth Edwards Lucasfilms STORY THE LEGEND OF TARZAN Tarzan's Mother David Yates Dark Horse Entertainment FORGET ME NOT Eve Lance Roehrig and Quicksilver Films Alex Holt United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company SURVIVOR Lisa James McTeigue Nu Image / Millennium Films THE YOUNG VICTORIA Lady Flora Jean-Marc Vallée JK Films Hastings RIGHT HERE, RIGHT NOW Matthew Newton STAR WARS EPISODE III Mon Mothma George Lucas Jak Australia THE MATRIX REVOLUNTIONS Officer Wirtz Andy and Larry The Burly Man Wachowski Productions THE MATRIX RELOADED Officer Wirtz Andy and Larry The Burly Man Wachowski Productions AVATAR Dash Jian Hong Kuo Exile Productions Television Production Character Director Company TIN STAR S.1, S.2 & S.3 Angela Worth Various Kudos for Amazon THE FALL - S3 Joan Kinkhead Various BBC THE SECRET Hazel Nick Murphy Hat Trick/ ITV ENDEAVOUR Annette Bryn Higgins ITV Richardson GLITCH Elishia -

Victoria & Abdul

Victoria & Abdul For those Anglophiles who want another immersion in the warm, luxurious stew of the British monarchy, look no further for your latest fix than “Victoria and Abdul,” an engaging if utterly predictable dip into late Victorianism by a whole passel of old British pros, plus an attractive newcomer. All you need to know is that Dame Judi Dench rules this film as Queen Victoria, way late in her reign, alienated from her son (the future Edward VII), sour as vinegar from her unending rule, and looking for some—any—breath of the novel and the fresh. As she herself admits when challenged in the film: ”I am cantankerous, greedy, fat; I am perhaps, disagreeably, attached to power.” Her relief comes in the form of one Abdul Karim, a young, literate Indian Muslim (Ali Fazal) who is selected to come to London from Agra in 1887 to deliver a special commemorative coin to Her Majesty on the occasion of her Golden Jubilee. Abdul is supposed to be invisible to the Queen, but instead he catches her eye, then her mood, and finally, her spirit to the point where he becomes her teacher, or “munshi,” in all things Muslim and Indian as well as serving as her clerk. Theirs is a relationship which appalls her family—including the Prince of Wales (a bombastic Eddie Izzard)— and the court—especially in the person of Sir Henry Ponsonby (the uptight Tim Pigott- Smith) but which lasted until the Queen’s death in 1901. Sound familiar? Of course, we are in the same realm as the earlier “Mrs. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

RECONNAISSANCE Autumn 2021 Final

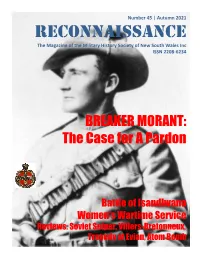

Number 45 | Autumn 2021 RECONNAISSANCE The Magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales Inc ISSN 2208-6234 BREAKER MORANT: The Case for A Pardon Battle of Isandlwana Women’s Wartime Service Reviews: Soviet Sniper, Villers-Bretonneux, Tragedy at Evian, Atom Bomb RECONNAISSANCE | AUTUMN 2021 RECONNAISSANCE Contents ISSN 2208-6234 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 Page The Magazine of the Military History Society of NSW Incorporated President’s Message 1 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 (June 2021) Notice of Next Lecture 3 PATRON: Major General the Honourable Military History Calendar 4 Justice Paul Brereton AM RFD PRESIDENT: Robert Muscat From the Editor 6 VICE PRESIDENT: Seumas Tan COVER FEATURE Breaker Morant: The Case for a Pardon 7 TREASURER: Robert Muscat By James Unkles COUNCIL MEMBERS: Danesh Bamji, RETROSPECTIVE Frances Cairns 16 The Battle of Isandlwana PUBLIC OFFICER/EDITOR: John Muscat By Steve Hart Cover image: Breaker Morant IN FOCUS Women’s Wartime Service Part 1: Military Address: PO Box 929, Rozelle NSW 2039 26 Service By Dr JK Haken Telephone: 0419 698 783 Email: [email protected] BOOK REVIEWS Yulia Zhukova’s Girl With A Sniper Rifle, review 28 Website: militaryhistorynsw.com.au by Joe Poprzeczny Peter Edgar’s Counter Attack: Villers- 31 Blog: militaryhistorysocietynsw.blogspot.com Bretonneux, review by John Muscat Facebook: fb.me/MHSNSW Tony Matthews’ Tragedy at Evian, review by 37 David Martin Twitter: https://twitter.com/MHS_NSW Tom Lewis’ Atomic Salvation, review by Mark 38 Moore. Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-532012013 © All material appearing in Reconnaissance is copyright. President’s Message Vice President, Danesh Bamji and Frances Cairns on their election as Council Members and John Dear Members, Muscat on his election as Public Officer. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. 'Elizabeth R·. BBC (1992). 2. D. Cannadine. 'The Context. Perfonnance and Meaning of Ritual: The British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition". c. 1820-1977'. in The Inven tion of Tradition. E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger (eds) (Cambridge. 1983) 101-64. Also see his 'Introduction: divine rights of kings'. in Rituals of Royalty. Cannadine and S. Price (eds) (Cambridge. 1987) 1-19. 3. 'Tradition. Continuity. Stability. Soap Opera'. The Economist. 22 Oct. 1994. 32. 4. E. Hobsbawm. 'Mass Producing Traditions: Europe. 1870-1914'. Invention of Tradition. 263-307. 5. Ibid .• 282. 6. 'The Not So Ancient Traditions of Monarchy'. New Society. 2 Jun. 1977. 438. This was a preliminary version of the essay that appeared in the Hobsbawm collection. 7. 'British Monarchy and the "Invention of Tradition"'. Invention of Tradition. 122. 8. Ibid .• 124. 9. Cannadine quoting Lady Longford. ibid .• 141. 10. Ibid .• 161. 11. D. Cannadine. The Pleasures of the Past (London. 1989) 30. 12. Ibid. 13. Ibid .• 259. 14. L. Colley. Britons, Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (New Haven and Lon don. 1992) ch. 5; idem. 'The Apotheosis of George ill: Loyalty. Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820'. Past and Present. no. 102 (Feb. 1984) 94-129. See also M. A. Morris. 'Monarchy as an Issue in English Political Argument during the French Revolutionary Era'. PhD thesis. University of London. 1988. esp. ch. 7. 'Royalist Ritual and the Support of the State'. 15. L. Colley. 'Whose Nation? Class and National Consciousness in Britain 1750-1830'. Past and Present. no. 113 (November 1986) 117. 16. -

The Corazzieri, the Italian Corps of Cuirassiers

The Corazzieri, the Italian Corps of Cuirassiers The Origins The first trace of a company of Archers and Squires entrusted with task of guaranteeing the security of the residence and of the members of the House of Savoy dates back to the 15th Century. The corps was established when Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, (1553-1580) nicknamed “Testa di Ferro” (Ironhead), created the “Guard of Honour of the Prince”, a company of about fifty men under the command of a captain who had their baptism of fire in the victorious battle of St. Quintin, on the 10th of August 1557. After having been constantly amplified, in terms of men and tasks, in the 1630s the unit comprised at least 400 men divided into four companies, one of which was the “Company of His Highness’s Cuirasses”, whose members began to wear the monogram of the State authority on the breastplate of their armours. Despite the constant change in institutional forms, this tradition has been handed down to our days. From Victor Amadeus II to Victor Emmanuel I Under the long reign of Victor Amadeus II (1675-1730), the different units of the security and ceremonial guards were merged into a single corps called the "Guardie del Corpo" (“Body Guards”), which was subdivided into four companies of Body Guards, one company of the Guards of the Door and one company of the Swiss Guards. From then and through another century, few changes were made to the uniforms or to the composition of the unit, which was deployed in normal institutional tasks as well as in frequent war campaigns, where they distinguished themselves for their excellence.